Real-Life Stories From 'The Titanic'

|

| |

SUNKEN DREAMS

Tales of life, and death, from a night to

remember

he great ship sank

with a slight gulp, witnesses say.

It was early morning, April 15, 1912, 700 miles east of Halifax, Canada.

RMS

Titanic, on her maiden voyage from Southampton, England, to New

York

City, had sideswiped an iceberg 2 hours earlier, popping rivets and

buckling the hull's iron plates deep below the waterline.

he great ship sank

with a slight gulp, witnesses say.

It was early morning, April 15, 1912, 700 miles east of Halifax, Canada.

RMS

Titanic, on her maiden voyage from Southampton, England, to New

York

City, had sideswiped an iceberg 2 hours earlier, popping rivets and

buckling the hull's iron plates deep below the waterline.

|

|

PHOTO: Mansell

Collection - Time Inc.

|

Furiously, the sea

rushed in, flooding one watertight compartment after another of the ship's

supposedly unsinkable hull until the bow was submerged and the tail stood

upright against the black sky. At 2:20 the ship slid below the surface

completely.

So much for the physics. But what captured the public's attention was that

night's human tragedy. Titanic set sail carrying some 2,200

people -- millionaires, immigrants, 13 honeymoon couples and an eight-man band

that played to the bitter end -- and lifeboats for just over half of them. In the

end 712 were rescued; the rest drowned or froze in the water. "It was the

biggest ship in history, filled with celebrities of that time," says James

Cameron, director of the blockbuster film Titanic, which has become the

first film to gross more than $1 billion worldwide, been nominated for a

record-tying 14 Oscars and propelled actors Leonardo DiCaprio and Kate Winslet

into superstardom's rarefied realm. "It would be like if you took

a jumbo jet filled with half the stars in Hollywood and crashed it into the

Washington Monument.

Yet Titanic's sinking was not instantaneous, and in her dying moments

fateful choices were made. A look at her real-life victims includes both tales

of valor and too-human frailty.

|

Smith (days before the disaster) was respected by his

crew and admired by the passengers.

Known as "the

millionaire's captain," Smith was one of the most experienced and charming ship's

masters on the Atlantic run.

Captain

E.J. Smith

Titanic's enduring enigma

Four months before the sinking, Smith was

toasted by wealthy New Yorkers at a dinner in his honor. Known as "the

millionaire's captain," he was one of the most experienced and charming ship's

masters on the Atlantic run. So why did Smith steer his fully loaded ship at

high speed through a field of icebergs in the middle of night? The captain took

the answer with him to the bottom of the Atlantic, but nothing in his past

suggests a reckless streak. Edward John Smith was born in landlocked

Staffordshire, England, in 1850 and went to sea in his teens as a "boy" on a

sailing ship bound around the globe and captained by his half-brother Joseph.

As a captain he joined the White Star Line in 1880 and eventually skippered the

maiden voyages of many of the line's newest steamers, including Titanic's

sister ship Olympic. Once, while Smith was at the helm, the Olympic

mysteriously struck an object while crossing the Atlantic and had to be taken

to a Belfast shipyard for repairs to a propeller.

Smith, married with one daughter, was contemplating retirement after the

Titanic crossing. But given what happened, says a distant relative, Pat

Lacey, 75, "it's a jolly good job he went down with her instead."

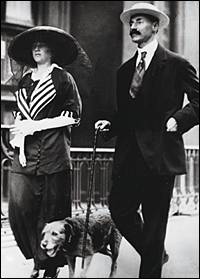

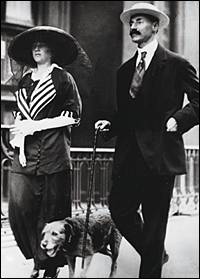

SIR COSMO AND LADY DUFF GORDON

A lady's careless words came back to haunt her

As the Titanic slipped

beneath the North Atlantic, London-born Lucy, Lady Duff Gordon, a dress

designer with chic shops in London and New York City, turned to her secretary

aboard lifeboat No. 1 and said, "There is your beautiful nightdress gone."

Lucy's ill-timed comment, uttered over the screams of 1,500 victims

stranded in the water, started a fateful chain of events. "Two of the sailors

said, `It's all right for you -- you can get more clothes, but we have lost

everything,' " reports Sir Andrew Duff Gordon, Lucy's great-nephew. Her

sympathetic husband, Sir Cosmo, who had been given the nod to get into the

lifeboat with his wife, later gave each of the seamen 5 pounds ($360

today) to replace their belongings -- a gesture that inadvertently sealed the

couple's fate.

Back in London, gossipy members of society accused Duff Gordon of bribing the

crew to row the two-thirds-empty craft from the scene without helping victims

in the water.

In May 1912, a British inquest cleared Duff Gordon of the charge.

But the damage to the couple's reputation was permanent. Shunned in some

circles, the Duff Gordons, who were unable to have children, drifted apart,

though they never divorced. Cosmo died in 1931. Lucy's business thrived for

a time but went bankrupt before her death in 1935. For them at least, says

Lucy's biographer Meredith Etherington-Smith, "it was almost worse to survive

than to go down."

DOROTHY GIBSON

The silent-film star dressed for disaster

For a moment, it looked as if one of the lifeboats would follow Titanic

to the bottom. Water gushed through a hole in the bottom until, in the words of

Gibson, a 28-year-old silent-screen actress from Hoboken, N.J., who was aboard

with her mother, Pauline, "this was remedied by volunteer contributions from

the lingerie of the women and the garments of the men."

In 1914 she married Jules Brulatour, the wealthy New York film distributor with

whom she had been having a long-term affair and who had called her back from

her European vacation just days before she boarded Titanic. The unhappy

union ended in divorce two years later. Gibson, "a very vivacious sort,"

according to historian Don Lynch, died of a heart attack in Paris in 1946. Many

remembered the actress for her starring turn in Saved from the Titanic,

a silent film made one month after Gibson was rescued. Her costume: the very

dress she had worn the night of the disaster.

MADELEINE AND

JOHN JACOB ASTOR

An American millionaire and his wife bade farewell forever

John Jacob and Madeleine Astor's Airedale, Kitty (in this ca. 1911 photo), was lost,

but two dogs did survive.

John Jacob and Madeleine Astor's Airedale, Kitty (in this ca. 1911 photo), was lost,

but two dogs did survive.

On a vessel flush with tycoons, New Yorker John Jacob Astor IV stood out as the

richest. He boarded at Cherbourg with an entourage that included his wife,

Madeleine, a manservant, a maid, a nurse and his Airedale, Kitty. First-class

staterooms like theirs -- richly paneled suites with working fireplaces and

separate quarters for servants -- cost as much as $4,000 for the voyage,

equivalent to a staggering $50,000 today.

But there was more to Astor than the $87 million fortune he made through real

estate and his family's fur-trading empire. After graduating from Harvard, he

patented such inventions as a turbine engine, a bicycle brake and a "vibratory

disintegrator" used to produce gas from peat moss.He wrote a science-fiction

novel about life on Saturn and Jupiter and financed his own Army battalion

during the Spanish-American War. His first marriage, to Ava Willing of

Philadelphia, lasted 10 years and produced two children.

But his second marriage, to Madeleine Force in 1911, caused a scandal. She was

18 at the time, and he was 46. To escape wagging tongues, the couple took an

extended honeymoon in Europe and Egypt (where they joined his friend Molly

Brown). By the time they boarded Titanic, Madeleine was five months

pregnant. "They wanted the baby born in America," says historian Don Lynch.

Astor mentioned his wife's "delicate condition" when asking an officer if he

could take one of several empty seats in her lifeboat, but the officer refused.

Astor took it like a gentleman. He lit a cigarette and tossed his gloves to his

wife. Several days later his partly crushed, soot-stained body was found

floating in the Atlantic with $2,500 in a pocket. Experts believe Astor may

have been hit by a falling smokestack.

In the years that followed, Mrs. Astor, who was twice remarried and died in

1940, rarely spoke of the tragedy, except to recall her final memory: Kitty, on

deck, pacing frantically. On Aug. 14, 1912, she named her newborn son, a future

playboy, John Jacob Astor V.

|

MOLLY BROWN

Not even an iceberg could slow down this dynamo

On board Titanic, Brown (ca. 1900) was

shunned by some members of high society.

On board Titanic, Brown (ca. 1900) was

shunned by some members of high society.

Mrs. J.J. Brown's 1912 tour of

the Old World had been a smashing success. She bought antiquities in Egypt,

hobnobbed with John Jacob Astor, one of the world's richest men, and visited

her daughter, Catherine Ellen, at a Paris finishing school. Even after news of

a sick relative cut short her stay, Brown was lucky enough, or so she thought,

to book a ticket home on the finest ship afloat: Titanic.

The steamer went down, but not the "Unsinkable" -- as she came to be known -- Molly

Brown. Loaded into lifeboat No. 6 (capacity:65) with 24 women and two men,

Brown, in a black-velvet, two-piece suit, argued fiercely with Quartermaster

Robert Hichens, who refused to return to the wreck site for fear survivors in

the water would swamp the boat. To fight the bitter cold, Brown taught the

other women to row and shared her sable coat. And when Hichens dismissed a

flare fired by an approaching ship as a "shooting star," Brown threatened to

throw him overboard (although not, as in the 1964 movie musical bearing her

name, while waving a pistol). Once in command, she ordered the women to row to

safety.

Brown had proved her mettle yet again. Born Margaret Tobin in Hannibal, Mo., in

1867, she left the poverty of her hometown behind and moved when she was 18 to

the boomtown of Leadville, Colo., to find "work and a rich husband," says her

great-granddaughter Muffet Brown, a Los Gatos, Calif., graphic designer. She

met prospector James Brown, 13 years her senior, at a church picnic and married

him in 1886 -- seven years before he struck gold at the Little Jonny Mine and

began building his $5 million fortune.

Molly, though, couldn't abide being confined to their Denver mansion. She

traveled, often with her son Lawrence, to Europe and mastered several languages

before separating from James in 1909. After the ship sank (with 13 pairs

of her shoes and a $325,000 necklace), Brown raised funds for poor survivors

and fought for women's suffrage. But most of all, Brown, who died after a

stroke in 1932, enjoyed her fame as the pluckiest of Edwardians. "Simple Brown

luck," she said after the wreck. "We're unsinkable."

J. BRUCE ISMAY . . .

Visits:

Return to Zolt's Front Door

Return to Zolt's Front Door

Return To Index

Return To Index

This page hosted by

Get your own Free Home

![]() he great ship sank

with a slight gulp, witnesses say.

It was early morning, April 15, 1912, 700 miles east of Halifax, Canada.

RMS

Titanic, on her maiden voyage from Southampton, England, to New

York

City, had sideswiped an iceberg 2 hours earlier, popping rivets and

buckling the hull's iron plates deep below the waterline.

he great ship sank

with a slight gulp, witnesses say.

It was early morning, April 15, 1912, 700 miles east of Halifax, Canada.

RMS

Titanic, on her maiden voyage from Southampton, England, to New

York

City, had sideswiped an iceberg 2 hours earlier, popping rivets and

buckling the hull's iron plates deep below the waterline.

John Jacob and Madeleine Astor's Airedale, Kitty (in this ca. 1911 photo), was lost,

but two dogs did survive.

John Jacob and Madeleine Astor's Airedale, Kitty (in this ca. 1911 photo), was lost,

but two dogs did survive. On board Titanic, Brown (ca. 1900) was

shunned by some members of high society.

On board Titanic, Brown (ca. 1900) was

shunned by some members of high society.  Return to Zolt's Front Door

Return to Zolt's Front Door