The hanging

Hanging was first used as a method of execution in Persia (now Iran) about 2500 years ago for male criminals only, (women were strangled at the stake for the sake of decency!) It was considered ideal as it produced a highly visible deterrent without the blood and gore of beheading, being simple and cheap to perform and not requiring a skilled executioner.

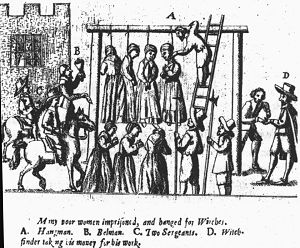

In England, hanging was the principal form of execution from Anglo-Saxon times up to abolition in 1964. In early times the prisoner was either hanged from a branch of a convenient tree or from a simple gallows where he was turned off using the back of a cart or from a ladder. There were hundreds of executions a year in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth centuries with the greatest number being carried out at Tyburn near what is now Marble Arch, in London.

As in early Persia, hanging apparently met the needs of justice well,

attracting large crowds who were at least supposed to be deterred by it,

but who more probably went for the general excitement and a day out

. (The modern expression Gala Day is derived from the Anglo-Saxon word

for gallows day.)

Hanging was also the main form of execution in most other countries

up to the end of the nineteenth century when there was a general trend

to abolition or to more humane methods of execution than

the form of hanging used at that time. It continues to be used in many

countries to the present day notably Egypt, Singapore, Malaysia, South

Korea, India, Pakistan, Japan, some African countries, Iran, Iraq, Syria,

Jordan, Kuwait and Libya, most of the Caribbean states and in three States

of America (although Washington & Delaware are the only States to have

actually carried out any hangings since the re-introduction of capital

punishment in America in 1976.

In the nineteenth century there was a general move towards less use of capital punishment in Britain and the number of executions began to decline. In 1820 there were 43, 17 in 1825 and only 6 in 1830. After that they seldom exceeded ten a year and it was often far fewer, except in times of war.

At the beginning of the nineteenth century there were an amazing two

hundred and twenty-five capital crimes including such terrible offenses

as impersonating a Chelsea pensioner and damaging London Bridge. By 1850

these had been reduced to just four (High Treason, murder, piracy and arson

in Royal Dockyards) largely by the efforts of Sir Robert Peel and a growing

tide of public opinion educated by the emergence of the Press and notable

figures of the day such as Charles Dickens and John Howard. Dickens also

campaigned strongly against public executions and finally succeeded in

1868 when Michael Barrett (a Fenian - the old name for the I.R.A.) became

the last man to be publicly hanged before a huge crowd outside Newgate

prison on May the 26th. for a bomb attack at Clerkenwell in London. Barrett

was hanged by Calcraft, who was noted for his short drops; but was said

to have died without a struggle unlike so many of Calcraft's other victims.

Calcraft retired in 1874 and was replaced by William Marwood.