Movie

reviews and articles

Movie

reviews and articles

Movie

reviews and articles

Movie

reviews and articles

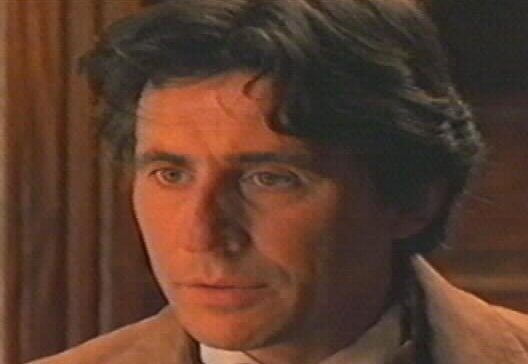

The man who for years was always described as a 'brooding Irish actor' lives on his own in Beverly Hills. From the outside it looks like any Los Angeles house, but inside it's definitely the home of an expatriate. There are masses of Irish poetry books, paintings of Irish landscapes, family accordions (which he plays) and even the shoes he wore as a schoolboy. Much more than an actor - he also develops projects, writes scripts and novels, and produces films - Byrne goes back home every summer 'to do movies about Ireland'. His two children, from his marriage to actress Ellen Barkin, go with him. "It's so easy to get caught up in mass culture here. It's important my children know they have another tradition and a heritage that's a gift to them". Now 48, Byrne's aquiline features are more craggy, but his sex appeal is as strong as ever. Madonna made no secret that she's a big admirer. "He's as talented as he is beautiful", she once declared. "Madonna was definitely after him", says a friend. "He found it amusing". (Photo: Stephen Danelian/Outline)

Chris, Gianni and the Flap of the Tent

Chris O'Neill and Gianni Versace. Two men with little in common, apart from showmanship and death in Miami.

by Gabriel Byrne

© Copyright: Magill (September 1997)

Some weeks ago I was invited by Gianni Versace to be his guest in Paris, the occasion was the unveiling of his much anticipated 1997 collection. Never having attended a fashion show I decided to go along more out of curiosity than interest. It was a glamorous occasion. Red carpets, limousines, champagne, beautiful models, Demi Moore, Naomi Campbell - dancing in the Ritz ballroom 'til dawn. By those in the know of such things, the show itself was declared a triumph. Gianni, who I had met briefly on a few previous occasions, has me placed next to him and Demi at the sumptuous post show dinner. He seemed tried, drained. He said he always felt like this after the stress of a major show and was looking forward to returning to his house in Miami for a vacation. Did I know the city, he asked. "Vaguely," I replied. Then I told him of a friend of mine, an actor from Dublin call Chris O'Neill who had died there, just some weeks before. I told him some of the stories and images that come instantly to mind when I think of my friend Chris. The first time I saw him he was standing with his back to the counter of the Sword Pub in Camden Street. Cassius in a river of light. The curly mop of hair, the lean smiling face, the moustache of Guinness and the elegantly disheveled clothes. His legs apart, hands in pockets, head to one side, unconsciously mimicking an early photograph of Joyce. In 1978 I had just been cast in The Riordans, largely because of Chris, with whom I had worked in the Project Theatre. He became my agent and my friend. He was generous, loving, sometimes unreachable in every sense of the word, (he was here a second ago) he was raconteur, svengali, manipulator, a wheeler dealer, a rogue, a rascal, hail fellow well met. The soul of kindness, the enemy of convention. An actor who truly loved acting, friend, father and sometimes foe. But once met never forgotten. The misshapen pockets filled to overflowing with keys, paper, biros, pound notes, newspaper cuttings, betting slips, keys, cigarettes and forgotten sandwiches. One day in Baggot Street we began to argue fiercely, he had been my agent for some time and I demanded, in a bout of diligence, to see the receipt of a cherub I should have received from RTE. "It's in your file," he informed me, and called me a Doubting Thomas, a man of no principle, a bad friend. And I in return asked if he was putting my money on a horse or what. We stared white-faced at each other outside Searson's. "Right," he said finally, "come with me" and we walk in a furious cold silence to his office, he pulls open a drawer and with great theatricality flings a file with my name hand-written on it before me. I tell him I am sorry, I should never have doubted him. I open the cover and the sole contents slip out: a single smiling photograph of the actor Jim Reid. I chase Chris around the desk, down the stairs and into the street and at last I catch up with him, and breathless we stare at each other and then we begin to laugh and laugh. Later I left for London to seek my fortune, my rather haughty new agent asked me who handled my affairs in Dublin and I gave her his office number. Her eyebrow raised as she was told that Chris should be back in a few minutes, his pint is still on the counter and he is probably over in the bookies. I really had come to believe that The Sword was his office. One day at cast rehearsals for the Riordans, he thrust a copy of a well known provincial newspaper before me. At the top of the page ran the legend "Show business Awards 1978". We had been nominated along with our fellow cast members as the showbiz personalities of that year. "Do you think Frank Sinatra will show up?" said Tom Hickey: "you never know", said Chris. I scanned the categories again; best singer 1978 nominations: Frank Sinatra, Elvis Presley, Mick Jagger, Tom Jones, and Big Tom. That is going to be a closely contested category, says Chris. Best Group of the Year are The Beatles, The Beach Boys, The Rolling Stones, Jerry Silicone and the Shoeshiners. "Actors?" said Hickey - Al Pacino, Robert DeNiro, Dustin Hoffman, Robert Duvall and the cast of the Riordans. "I'd say we're in with a chance," said Chris. And so it was that myself and Tom Hickey and Chris found ourselves wending our way to the awards ceremony. We came to a small sleepy village and enquired of a youth eating chips by a wall whether we were headed in the right direction. He peered into our car, his face beaming with recognition. "Jaysys, it's the Riordans." We asked again whether we are on the right road. "Jaysus I don't know, I don't know where it is," he finally admitted, "de yis know yourselves" he asked. At last we reached our destination and are directed to the hotel, an unctuous man with the look of a slieveen, wearing a pioneer pin, greets us in a precious voice. He is the Big Man, organizer of the whole scam. "Any chance of a sandwich?" Chris asks. "Oh you'll be looked after lads, never fear." Em, where are the other nominees?" Chris asks. "Well so far you're the only ones, but we're expecting Jerry Silicone any minute. Margo got a puncture in Mulhuddard." "So you're not expecting Frank Sinatra any time soon then," said Tom Hickey. "Well begob lad you'll never know, I'll get ye them sandwiches." We sat looking at each other, Chris in his usual state of attractive dishevelment, Tom smart as a whip and scarily calm and myself in a white suit looking like 'Our man in Havana'. When we had repaired to a nearby bar, and were suitably fortified, Tom Hickey spoke. "Look lads, if this is a flap of the tent job, we'll give it an hour and then we're out." "What does that mean?" I asked. "It refers," explains Tom, "to a celebrity engagement outside the confines of the city, usually in a marquee, where the only recourse in a situation above and beyond the call of duty is to crawl through a flap in the tent and to make good your escape, hence flap of the tent." In other words, exploitation of the guairle by the gombeen. There was only one entrance to the hall which was packed to capacity with punters who had paid in to witness the glittering awards ceremony. A small fat woman sat hunched over a turnstile, dressed in a white coat with Maor inscribed in red. She was the sliveen's mother. "That'll be 6 pounds," she said without looking up, "6 pounds!" Chris said incredulously, "but we're the nominees." We forked out the money, the pioneer pin motioned us toward center stage. "Ladies and Gentlemen," he intoned into the microphone, "put your hands together and give a rousing welcome to some very special guests. You have seen them on the screen and now you see them live here on this stage, the nominees for show business personality of 1978 are ..." there was silence. A drum roll - "Al Pacino, Robert DeNiro, Dustin Hoffman, who fortunately cannot be here to night, and ladies and gentlemen the winners are Michael, Pat and Tom from the Riordans." Thunderous applause. Having seen off all competition from England, America and the rest of the world, we stand the disputed victors with our plastic trophies, smiling, bowing, starving and dying of the drought, as Tom Hickey in a fierce whisper keeps repeating "Flap of the Tent, Flap of the Tent." At two o'clock in the morning we wait in a line at the chip van in the town square. We are told by a swaying drunk to get up the yard, that there's a smell of shite off us and we should go back to the Leestown where we came. "Fame," says Tom Hickey, shaking his head, fame." "I hope," said Gianni, smiling when I had finished, "that your friend would not call this a flap of the tent job," and he waved his arm around the beautiful room. "I doubt," I said, "he would." It was a still beautiful day in Los Angeles, when I heard of Chris' death. I had been reading in the garden, and I dosed off and did not hear the phone. Later when I played back the message and heard her voice, my whole body weakened in shock. It was Aisling, his daughter. Her voice was calm, almost matter of fact, Daddy passed away she said - he looked at me and smiled and closed his eyes and then he died, she was saying. In Miami, I thought to myself, of all places. Two days after the Paris show, Gianni was dead too, murdered by a madman. Donatella his sister said he died like an emperor, facing the sky, his hands thrown out behind him. I like to think they've met somewhere, these men who died in the same town within weeks of each other. I know they'd get on. By the way, I still have the award and the slieveen went on to greater things in national politics. Chris, I miss you, you gave it the lash. I'll see you on the other side of the tent...

A star is Byrne....

Actor Gabriel Byrne has entered into a new production deal with Sony Pictures because word-of-mouth on their first association, Mad about Mambo, is extremely hot. Mel (Bean) Smith will direct The Lying Laird, a comedy based on the true story of an official who embezzled a large sum of money in order to buy a Scottish noble title. The other project on the boil is Early Bird about a B-17 bomber crew who crash-land in Ireland during the Second World War to be directed by Simon (Free Willy) Wincer.

(Film Review January 1999)

By Roger Ebert

By Hal Hinson

Washington Post Staff Writer

July 10, 1992

The major issue to be resolved in "Cool World," Ralph Bakshi's new venture into the "Roger Rabbit"-style marriage of animation and live action, is whether Kim Basinger is more obnoxious as a cartoon or as a real person. Basinger plays Holli Would, a curvaceous pen-and-ink nymphet who lives in a cartoon universe called "Cool World." This animated parallel dimension was created, Holli included, by Jack Deebs (Gabriel Byrne), an underground cartoonist who, without warning, is suddenly whisked into his own fantasy creation. The catalyst for this abduction is Holli herself, who lusts so mightily for life in the real world that she beckons Jack from his realm to help her make it across. Holli is a creature of lusts, as every inch of her anatomy illustrates. As a cartoon, Holli incessantly gyrates and grinds as if she's gulped a handful of Mexican jumping beans. And when the transformation from cartoon to flesh-and-blood actress occurs, the body language remains the same. The results fall far short of Jessica Rabbit's mark. What we get from Basinger here is the spectacle of the actress executing her impersonation of Marilyn Monroe while trying to twist herself into a human pretzel. It's not funny and, unless I'm the only human alive not turned on by an animated striptease, it's not sexy either. That doesn't leave much. The script (by Michael Grais and Mark Victor) includes a second relationship between a "noid," as the humans are called in the Cool World, and a "doodle," the name for animated characters. The noid is a detective named Frank (Brad Pitt) who was thrown into the Cool zone after he crashed his motorcycle, and his cartoon squeeze a foxy brunette. The couple are tight but they have a problem: Noids and doodles can't ... do it. Doing it, in fact, figures dramatically in the plot. It was "doing it" with Jack, a noid, that transformed Holli into a real person. So, like, couldn't Frank and his girl ... you know ... and transform her into a real person? What are the rules anyway? Technically, Bakshi's work is uneven; some of the characters in his Cool universe are hilarious, while others are flat. And the combination of live and animated action falls a notch below state of the art. The look of the production is fresh and, at times, even thrilling, but for the film to work, Bakshi has to make his artificial world seem real, and he never does. That's the animator's bottom line, and Bakshi leaves it blank. His only contribution is the irreverent, Vargas-girl variety sexuality that he made his trademark in" Fritz the Cat" and "Heavy Traffic." But is it really an innovation to provide a realistic jiggle to an animated breast?

By Desson Howe

Washington Post Staff Writer

December 03, 1993

In "A Dangerous Woman," you know Debra Winger is a bomb about to go off. The title -- not to put too fine a point on it -- is a dead giveaway. And when Winger almost clubs a woman to death in the opening scene, you know bizarre things are in store. As Martha, Winger is a "childlike spirit captured in the body of an awkward woman" -- as Gramercy Pictures' press notes puts it. Whether that means mentally impaired or not is unclear. But she's called a "screwball" behind her back. Timid and thickly bespectacled, she lives a sheltered existence in a guest house next to her aunt (Barbara Hershey), on whom she depends for emotional security. That near-clubbing comes when bitter wife Laurie Metcalf intentionally plows her car into Hershey's front porch. Climbing out of the battered automobile, gun in hand, Metcalf accuses Hershey of having an affair with her politician-husband John Terry -- who happens to be there. Winger, who's been watching the altercation in horror, retreats to her house and comes back with the hammer. Before she brings the thing down on Metcalf's head, however, she is stopped. So is Metcalf. The incident is forgotten. But we know something's ticking away. In producer/writer Naomi Foner's increasingly laughable scenario, Winger undergoes a systematic shafting from everyone around her, including Hershey, who treats her like an unwanted child, and Winger's fellow employees at the dry cleaners where she works. When Winger meets drunken Irish handyman Gabriel Byrne, who gets a job fixing that front porch, it's love at first near sight. They're birds of a feather. He sees how mistreated she is. She sees his heart of gold under all that boozy breath. In one private encounter, the besotted Irishman bursts into tears, buries his head in her lap and begs for absolution. "Oh, Martha," he whimpers. "You're like a primitive thing that's never been spoiled." Their tentative affair and various other episodes continue with slow, arbitrary and unintentionally amusing abandon. The most significant development is a growing tension between Winger and sleaze ball David Strathairn, boyfriend of one of her co-workers. Like most movie naifs, Winger speaks the truth no one else is capable of, and naturally no one believes the addled Cassandra. She also sees -- with contrived regularity -- society's deceptions. After the gun-and-hammer scene, for instance, Winger peers through a window to see Hershey making illicit love with Metcalf's husband. So they were having an affair! Winger happens to look up as Strathairn slips money from the dry cleaners' till into his underwear. But Strathairn successfully accuses her of pilfering. What's a harassed "screwball" to do? Winger, who looks like one of Gilda Radner's "Saturday Night Live" caricatures, throws herself into the acting task. But her talents and enthusiasm are counterproductive here. Her eye contact veers away from people, "Rainman" style. She squints so theatrically behind those glasses, you want to knock them off. Her ungainly waddle is meant to be poignant, but it just looks like she's imitating TV's Urkel. If mistakes are things to recover and learn from, "A Dangerous Woman" is the lesson of her career.

By Roger Ebert

Observe the way Debra Winger plays her character in "A Dangerous

Woman," and you will learn something about the alchemy of acting. She

doesn't look particularly different in this film - aside, of course,

from the details of makeup or hair style that help women express

their beauty. You can always see that it's Debra Winger. But she

projects such a different essence in the film, so profoundly

different, that you wonder how she's doing it.

She plays a woman named Martha, who is slow, or somewhat

retarded, or whatever word you want to use. She can function in the

world, and even hold a job at the dry cleaners, but she is odd in her

behavior, and children in the street feel safe to follow and mock

her. Her home is the guest cottage next to the big house occupied by

a close relative, Frances (Barbara Hershey), who has sort of

inherited Martha as a responsibility.

Winger must have studied women like Martha in preparing for

her performance. She must have lived beside them, observing a hundred

different details. She puts them all together into a portrayal that

never seems made up of those details, however; everything is of a

piece, and after a time we are simply watching Martha, identifying

with her. Look at the way Martha studies the movements in the faces

of people she's talking to. She all but peers at them, looking for

clues, trying to read emotions and meanings. Look at the way she

walks, filled with purpose, concerned with getting from here to there

without false effort. Look at the way she stiffens when she is

treated unfairly. Look at how proudly she insists that she always

tells the truth.

The women live in a small town where everybody knows each

other, more or less. Frances is a bit player in local politics, and

it gradually becomes clear that she's the victim of a series of

affairs, that she tries to find herself through the assistance of

men, and usually fails. As for Martha, she hardly seems aware there

is such a thing as a sex life. Then one day an alcoholic handyman

named Mackey (Gabriel Byrne) comes drifting into their lives, looking

for work. It so happens that Frances' frame porch has

been caved in by an automobile driven by a jealous wife who thought,

correctly, that her husband was inside the house. Frances sends the

handyman away, but Mackey comes back anyway, and starts the job; he

needs the work so badly he has no choice.

Eventually Mackey will become involved with both women. But

it is not as simple as it might sound,

because he isn't bad - none of these people are bad - and in the

loneliness and desperation of these lives many things can happen. His

moral carelessness is fueled by alcoholism, which he acknowledges,

although the movie in general doesn't take it very seriously.

Mackey's involvement sets a plot into motion, a plot that

eventually involves another local man,

Getso (David Strathairn) a worthless petty thief at the dry

cleaners. Things happen. The movie is not really about the things

that happen - it's about the two women - but it's as if the

screenplay gets seized by a desire to tell the superficial story, and

forgets to tell the real one. There is a pregnancy and a killing and

a secret that cannot be shared, and it's all really just melodrama.

I guess human stories have to be linked up to the mechanics

of a plot in order to get financed, or to find an audience. No one

would have wanted to see a movie that simply watched and listened

with sympathy to the events in the daily life of a moderately

retarded woman. But why is it that violence has to be involved? Why

do so many plots depend on violence as the shortcut for creating

dramatic tension. What do Martha and her job and her simple hopes

have to do with all these distraught scenes in the police station,

and all that blood? Look at another current movie, "Ruby in

Paradise," which by setting itself free from the contrivances of

sensational plotting allows itself to be deep and true.

"A Dangerous Woman" raises more questions than it answers.

The handyman character is well-played by Byrne, and surprisingly

sympathetic, considering he sometimes behaves in an unprincipled way.

But he functions too much as an invention of the plot, dropped into

the story to busily make speeches and love. He doesn't have much to

do with the real lives of the two women. Then there is another

character handled carelessly: the wife of Frances' politician lover,

who drove her car into the porch. This woman reappears in the movie

at an important juncture and takes her husband back, and it's all

handled in long shots, without explanation, so that we can see she's

just a convenience for the screenwriter.

The movies are so seldom perfect that it's enough to find

something perfect in them. What's nearly perfect in "A Dangerous

Woman" is the Debra Winger performance. Her Martha seems to float

above the inventions of the plot, in a world of her own. She may not

know everything, but she knows what she knows, and acts on it to the

best of her ability. She does not lie. She will not hurt another. She

deserves her chance at happiness, and she knows it. It's quite a

performance.

By Roger Ebert

By Rita Kempley

Washington Post Staff Writer

June 21, 1991

Director Nick Broomfield turns a baleful eye on British sangfroid in "Dark Obsession," an infuriatingly detached first feature about the rich getting away with murder. Intended as a psycho-thriller, Broomfield's film is in fact a skimpily plotted rumination on what's rank among the privileged. Class-conscious and Thatcher-sore, it chides the gentry for an empty existence and moral turpitude. Gabriel Byrne, the broodmeister, is gargoylicious in the role of Hugo Buckton, an introverted aristocrat who becomes convinced that his wife, Virginia (Amanda Donohoe), is having an affair with a business associate. Given to NC-17-rated thoughts of passion and prodded by unreasoning jealousy, Lord Buckton grows more irrational the more he obsesses on the curvaceous Virginia. Under this wet blanket, passion smolders. Once a member of the Queen's Guard, Buckton has become a tippling dilettante who often carouses with his former cronies in the military. During one of these drunken sprees, he runs down a young woman who looks to his cuckold's brain vaguely like his cheating wife. Pheww, but it's only Lady Castlemere's cook, a commoner, so they leave her to die on the wet cobbles. It's very subtle. Only one of their number, the boyfriend of Buckton's sister (Douglas Hodge), feels any guilt whatsoever. He urges them to report the incident to the police, but the others persuade him to swear never to divulge their involvement. When the story leaks out anyway, the poor fellow is dealt with as barbarously as the good Piggy in "Lord of the Flies." Much of the story takes place at the Bucktons' ancestral estate, which to the family's discomfiture has recently been opened to the public. Hugo's mother (Judy Parfitt) is the imperious Lady Crewne, whose principal joy is lording it over Virginia, a beautiful commoner who is far too good for the over bred Crewne-Buxtons. A gothic spill from the pen of writer Tim Rose Price, they are a stock lot of stuffed shirts full of their own inbred self-importance. So what else is new?

By Roger Ebert

By Paul Attanasio

Washington Post Staff Writer

February 13, 1987

In "Defence of the Realm," an efficient but impersonal British thriller, Nick Mullen (Gabriel Byrne), an efficient but impersonal tabloid reporter, notes a whiff of scandal about Dennis Markham, a left-wing member of Parliament (Ian Bannen). When it turns out that Markham, who is privy to state secrets, shared a prostitute with an East German spy, he is forced to resign. A boozy colleague, Vernon Bayliss (Denholm Elliott), himself a Red from the days when Reds were Reds, tells the dogged Mullen that he doesn't know the whole story. When Bayliss mysteriously dies, Mullen smells a rat. Assisted by Markham's gorgeous secretary (Greta Scacchi), Mullen digs away, uncovering an intrigue involving double agents, American missiles in Europe, the "national security" debate, disinformation and the death of a borstal boy. Better than most, "Defence of the Realm" captures the flavor of a news room, although part of the realism is how boring it is. Still, it's nice to see a movie where a reporter actually goes to the library once in a while and puts seemingly unrelated puzzle pieces together. For the most part, director David Drury keeps things at a ripping pace. Another in producer David Puttnam's series of art school grad/commercial directors turned filmmakers, Drury knows how to compose a frame, and "Defence of the Realm" fills the eye with glossy visuals. But its slickness is also a little insular and off-putting -- it makes the movie a distant object -- and it doesn't help that Byrne is one of those swarthy, impenetrable British leading men who always have their neckties undone. Byrne rarely registers an emotion, so the plot just seems like an elaborate machine, and one that gets increasingly creaky. While you can accept "Defence of the Realm's" fantastic coincidences, it's rather harder to accept all the nefarious misdeeds the movie ascribes to the government, even if a series of horrendous coincidences have put them on the, uh, defensive.

End of Violence (1)

After his vapid "Wings of Desire" appendage "Faraway, So Close" Wenders' follow-up is, at least ostensibly, a thriller. Not, of course, the kind featuring Michael Madsen and left skulking unrented in every video shop, but a skewed union of genre staples (kidnapping, murder and adultery) with musings on communications technology, LA and the film industry itself. High in the Hollywood hills, schlock movie impresario Mike Max (Bill Pullman) is so absorbed in abusing his minions that the departure of his wife Paige (Andie McDowell) barely registers. What does get his attention, as well as that of watching government surveillance-expert Ray Bering (Gabriel Byrne), is his near-execution by a pair of redneck hoodlums. The rednecks are then found decapitated, while presumed killer Max is nowhere to be seen. For other directors, this intriguing premise would simply prompt countless "car-go-boom" action sequences; Wenders, however, takes the scenic route around his insubstantial storyline, and the result is playfully cerebral without veering into pretension. It also looks magnificent, every frame composed with an obvious love for the art of movie-making. Flawed, for sure, but welcome proof that Wenders didn't lose his talent when he started hanging out with Bono (Danny Leigh). Director: Wim Wenders, Cast: Gabriel Byrne, Bill Pullman, Andie MacDowell, Udo Kier. Running time: 1 hr 57, Out: 27 July.

End of Violence (2)

Wim Wenders' sprawling urban epic looks handsomely promising as it weaves together Big Brother technology with the glitz of Hollywood, but unfortunately the German author's result slowly slides into a convoluted sea of monotony. It feels like David Lynch's Lost Highway as if directed by Robert Altman. "Highway"-man Bill Pullman stars as a stressed-out Hollywood producer who is so wrapped up in the biz that his marriage with his trophy wife (Andie MacDowell) is falling apart. One night, he's abducted, implicated in a double murder and, mysteriously, is nowhere to be found. Only one of Big Brother's lensmen (Gabriel Byrne), has an inkling as to what might have happened. MacDowell is a pleasant surprise as she finally shows some genuine sexiness and edginess, but Pullman and Byrne are wasted in their complex but underdeveloped roles. The added twist of a government conspiracy and cover-up rings excruciatingly hollow, leaving Wender's latest barren and wingless (Tom Meek)

Enemy of State (1)

| In the '70s Hollywood responded to Vietnam

and Watergate with a series of marvelously tense political conspiracy thrillers. Films

like The Parallax View, Three Days of the Condor, and Francis Coppola's

masterful The Conversation reflected a new Orwellian age of wiretapping and

surveillance. The new suspensor Enemy of the State attempts to hark back to this

golden age of paranoid moviemaking, but without the timely context or sharp script. As

concocted by producer Jerry Bruckheimer (Con Air, The Rock) and director

Tony Scott (Top Gun, Crimson Tide), the film is just another hackneyed,

high-concept action flick that's more "oh brother" than Big Brother. You can

just imagine the studio pitch: Hey, let's catch up with bugger extraordinaire Harry Caul

(Gene Hackman's character from The Conversation) 25 years later and team him with

the Fresh Prince in a high-tech, low- |

Enter hotshot D.C. labor lawyer Robert Clayton Dean

(Will Smith), who bumps into old college classmate Zavitz while Christmas shopping for his

wife. (In pure red-

Enemy of State (2)

GABRIEL BYRNE makes an appearance as a NSA agent who attempts to throw Robert Clayton Dean off track and get him to hand over the incriminating videotape. Byrne is not only a gifted and highly acclaimed actor, but an Academy Award™-nominated producer as well. He executive-produced the film "In the Name of the Father," which earned several Oscar® nominations, including Best Picture, and also produced and starred in "Into the West," opposite Ellen Barkin. Beginning his acting career with the Abbey Theater and later joining the Royal Court Theater in London, the Dublin-born actor made his feature film debut in John Boorman's "Excalibur." Other European films include the acclaimed "Defense of the Realm" and "Hannah K." During this time he worked for several noteworthy European directors, including Costa-Gavras, Ken Russell, and Ken Loach. In 1990, he made his American debut in the Coen brothers' "Miller's Crossing." In 1995, he starred as Dean Keaton in "The Usual Suspects," which was nominated for two Academy Awards™. Early last year, Byrne starred in "Smilla's Sense of Snow," with Julia Ormond, and in the HBO film "Weapons of Mass Distraction," with Ben Kingsley. He was then seen in Wim Wenders' "End of Violence," and "Polish Wedding," with Lena Olin and Claire Danes. Most recently he played D'Artagnan in "The Man in the Iron Mask," opposite Leonardo DiCaprio, Jeremy Irons, John Malkovich, and Gérard Depardieu. He just completed a starring role in MGM/UA's "Stigmata," opposite Patricia Arquette. Lately Byrne has been dividing his time between writing, producing, and acting. His first book, "Pictures in My Head," was published in Ireland last year, where it became a critically acclaimed best-seller. "Pictures in My Head" was also published in the U.S. late last year. Byrne, who is a member of the Irish film board, is currently working through his production company, Plurabelle Films, where he is executive-producing the film "Mad About Mambo," which takes place in Ireland. Gabriel is in development on a number of other projects through his production company and Phoenix Pictures, where he has a first-look deal.

Frankie Starlight (1)

A Film Review by James Berardinelli

Ireland, 1995

U.S. Availability: 12/95

Running Length: 1:40

MPAA Classification: R (Profanity, sexual situations)

Theatrical Aspect Ratio: 1.85:1

Cast: Anne Parillaud, Gabriel Byrne, Matt Dillon,

Alan Pentony, Corban Walker, Georgina Cates, Rudi Davis

Director: Michael Linday-Hogg

Producers: Noel Pearson

Screenplay: Ronan O'Leary and Chet Raymo based on the novel The Dork of Cork by

Chet Raymo

Cinematography: Paul Lauffer

Music: Elmer Bernstein

U.S. Distributor: Fine Line Features

In English and French with subtitles

Frankie Starlight is ambitious, and, as is often true of movies that attempt too much, it's only partially successful. The film tries to follow multi-character stories in three different time frames, using a voiceover narrative to connect everything. Parts work; parts don't. Individual enjoyment of Frankie Starlight will largely depend upon which aspects of the film you choose to focus on. The wraparound story tells the tale of a modern-day Irish author, Frank Bois (Corban Walker), who is submitting his manuscript, Nightstalk (as in Nights Talk, not Night Stalk), to an editor. The book is immediately snapped up by Penguin Press for publication. An overnight success, Frank can't help but wonder whether his good fortune is due to the quality of his work or to his physical stature -- he's a dwarf. So he spends long hours in his hovel of a home, drinking wine and stewing in his loneliness. According to Frank, Nightstalk is an intermingling of astronomy with the stories of his and his mother's lives. Frankie Starlight's ambitious agenda is to transform the events of Nightstalk from text to screen images by means of lengthy flashbacks. These forays into the past start out with promise, as we first meet Bernadette (Anne Parillaud), Frank's mother, in Normandy, days before the Allied invasion. The setting soon changes to Ireland. Unfortunately, once the shores of France are behind Bernadette, the story starts glossing over key plot elements. Characterization becomes spotty as the film gropes for an anchor. Ultimately, Frankie Starlight is saved from incoherent oblivion by the birth of Bernadette's son. While Parrillaud's character continues to be paper-thin, the young Frank (Alan Pentony) quickly asserts himself. Soon, our attention -- not to mention our sympathy -- is vested exclusively in him. Bernadette becomes an almost unwanted distraction. The last third of the movie is by far the best. Taking place in the present, it brings together several loose threads from the past and weaves them into a touching love story. There's more emotional depth to Frank's relationship with his soul mate than is initially obvious, with director Michael Lindsay-Hogg handling this aspect of his film adeptly. The actors give heartfelt performances and the script avoids the trap of emotional artifice which ruins so many screen romances. Throughout the entire picture, stars are a key symbol. Frank eventually becomes an amateur astronomer, and many of the film's best sequences take place on a rooftop with thousands of points of light twinkling in the darkened canopy above. It is there that father-figure Jack Kelly (Gabriel Byrne) first teaches young Frank stories about the constellations, and there that the film draws to a close. More scenes like these would have been welcome. Connections, both made and missed, and the vagaries of life that lead us to react differently to the same people in diverse circumstances, form Frankie Starlight's thematic backbone. As with most of the film's other aspects, these are generally successful as they pertain to Frank, but rarely work with Bernadette. Parillaud's acting is too flat, and the sketchiness of the screenplay, which follows her life in broad strokes with few details, doesn't help. We're sure how and why Frank connects with others; the same can rarely be said about his mother. Frankie Starlight is more satisfying taken as a whole than when its individual parts are examined. The film is flawed, but there's still enough magic and genuine emotion to make for a pleasant movie-going experience. Affability is perhaps Frankie Starlight's strongest quality. No matter how many problems you uncover along the way, when the final credits roll, you're more likely to be smiling than frowning.

Frankie Starlight (2)

From the producer of My Left Foot (Noel Pearson) comes Frankie Starlight. Directed by Michael Lindsay-Hogg (Brideshead Revisted , The Object of Beauty), and starring Anne Parillaud (La Femme Nikita), Matt Dillon and Gabriel Byrne, Frankie Starlight is a film about love, life, laughter and the occasional miracle. Set in post-World War II Ireland, this is the story of Frankie and his mother Bernadette (Parillaud) who, as an 18-year old girl, left France smuggled aboard an American troop ship in return for sexual favors. Put ashore in Ireland, the penniless Bernadette gives birth to a son, Frankie. Through the kindness of customs officer Jack Kelly (Byrne), Bernadette is able to raise Frankie in Dublin. Jack teaches Frankie about the stars, sparking in him a lifelong mystical obsession with the cosmos. As an adult, Frankie weaves his love for and knowledge of astronomy into a novel based on his recollections of his mother's relationships with Kelly and an ex-GI (Dillon). After his book is published and he moves from isolation to potential celebrity, we discover how his mother's colorful exploits shaped Frankie's life. Frankie Starlight is based on Chet Raymo's best-selling novel entitled "The Dork of Cork." Raymo is a lecturer in astronomy at Stonehill College in Massachusetts, but has spent every summer for the last 16 years in the village of Vantry, County Kerry. It is the combination of his knowledge of the stars and time spent in Ireland that inspired him to write this magical tale of love and the stars. In the summer of 1993 Raymo sent his new novel to Noel Pearson, the producer of My Left Foot and The Field. "It was one of these books that had shamrocks and stars and leprechauns all over the cover so I didn't read it for ages" says Pearson. "Then one day I just flicked open the cover and there was a sticker in it saying, 'this could be your right foot.' That evening I began reading it at 9 pm and put it down at 7 am the next morning." Pearson then gave the novel to Michael Lindsay-Hogg who read it, met with Pearson a couple of times, and decided to direct the film. The story, which spans over 30 years, is set in France, Ireland and the United States. Shot on location in Ireland, a French village was constructed on a farm in County Kildare, and the Normandy scenes were done on beaches on the east coast of Ireland. The central character, Frank Bois, is played by two newcomers to the screen, Alan Pentony as the younger Frankie, and Corban Walker as the older one. Walker, a well-known sculptor in Dublin, was cast after just one screen test. Pentony was more difficult to find. Pearson explains, "We had a hard time finding young Frankie as we had to match him to someone fifteen years later. Nuala Moiselle, the casting director, searched the length and breadth of Ireland and finally stumbled upon Alan in Drogheda. He had the exact qualities we were looking for- fresh, warm and appealing." Anne Parillaud plays Bernadette, Frankie's beautiful French mother. Parillaud read the script once and her agent called to ask if she could do it. She flew from an island off Brittany on a Tuesday, met with Pearson and Lindsay-Hogg on Wednesday, and the deal was done on Thursday morning. By coincidence, Chet Raymo had used a picture of Parillaud for inspiration with the character of Bernadette while writing the novel. The character Jack Kelly, played by Gabriel Byrne, is a customs officer who befriends Bernadette after she is put off a U.S. warship while trying to escape from France to America after the death of both her parents during World War II. Jack for a brief time is Bernadette's lover, but then becomes more of a father figure to both her and Frankie. It is Jack who introduces Frankie to his lifelong interest in the stars. Byrne's reaction to reading the script was "I thought it was very simply written. It was just one of the best things I had read in a long time." The final stage in casting was to find an actor to fill the part of Terry, Bernadette's American lover. The script was sent to Matt Dillon, who had previously worked with Michael Lindsay-Hogg in the theatre, and he agreed to play the part. Interestingly enough, Dillon notes that "I always thought that because of my Irish background I would come here to play an Irish man, not an American." Chet Raymo was joined by Ronan O'Leary to co-write the screenplay, and by September 1994 Frankie Starlight was in production. It was shot for six weeks in Ireland and one week in Texas.

By Desson Howe

Washington Post Staff Writer

May 01, 1987

Ever had one of those weekends when leeches sucked your face, a friend went into convulsions and the guy next door kept impaling his hand on a nail? Ken Russell's "Gothic," which contains all of these elements and more, is for those of you who just have to have a blood-soaked sardonic yuk now and then. Russell, the man who gave the phrase "too much" new meaning, outdoes himself. "Gothic" ostensibly is about the famous weekend at the Villa Diodati when Lord Byron, Percy and Mary Shelley, Dr. Polidori and Claire Compton went into a literary huddle and came up with "Frankenstein" and "The Vampyre." True to demented form, Russell takes that idea to the limits: In his vision, Byron and friends were a sort of 19th-century Def Leppard -- famous young brats with nothing but devilish free time on their hands. In "Gothic," the Shelleys and Compton visit Byron and Polidori to indulge in the ultimate sex-and-spookout slumber party. Byron (Gabriel Byrne), a dandyish, jaded rake, asks his guests to play in a kind of extended Ouija-board mind game, wherein everyone must dredge up their deepest, darkest fears (to provide mulch for the forthcoming horrors). Things get out of hand. Four-posters squeak with sex escapades. There's perpetual thunder and lightning. Bugs scramble out of people's mouths. Women stroke snakes. And there are enough rats in the basement to send the Pied Piper back to music school. It's a Hell of a weekend. Russell's poets romp through mud, slime and nightmare fantasies whilst dressed in the height of Romantic fashion. By movie's end, they will have purged their fears and accrued a staggering dry-cleaning bill. Byrne plays a grim-faced, perverse Byron with great presence. Julian ("Room With a View") Sands once again bares his boyish good looks, not to mention buttocks. As a sleazy, sexually repressed Polidori, Timothy Spall seems so revoltingly convincing it makes you concerned for his family. Beyond the carnalia (and if you're still with us), "Gothic" happens to be strikingly shot, the special effects inspired, albeit gruesome. Although he slops his signature blood 'n' cleavage across the screen, Russell makes it slick, with dynamic cutting, vivid lighting and framing. Who knows, you might spot a little humor in this hyperbolic lunacy. On the other hand, after a cinematic orgy like this, you might long for 15 minutes with an evangelist.

By Roger Ebert

By Hal Hinson

Washington Post Staff Writer

November 09, 1987

Not too long ago, in her execrable movie "The Money Pit," Shelley Long spent most of her time with her house caving in on her head. Watching her new movie, "Hello Again," all I could think of was, "Where is that house when you need it?" In her early days on "Cheers," Shelley Long was like a cactus with brains; she was all prickly spikes and soliloquies. Now she has become the actress most likely to draw fire from passing motorists. In "Hello Again," she plays Lucy, a housewife married to a social-climbing plastic surgeon named Jason (Corbin Bernsen). You only need to watch Lucy walk a length of carpet to know everything important about her -- carpet being one of the many things in life that she has trouble with. Lucy is, as they say, accident-prone, which is another way of saying that all things edible spring to her blouse with alarming frequency. Either that or she chokes on them and dies, which is what happens when she nibbles on a South Korean chicken ball at her sister's. The movie, which was directed by Frank Perry and written by Susan Isaacs -- the team that worked together on "Compromising Positions" -- is like a sorry updating of "My Favorite Wife." One year after her death, Lucy is brought back from the dead by her sister (Judith Ivey), an occultist who put on her gypsy regalia to attend a Grateful Dead concert in '67 and hasn't taken it off since. Naturally, many things have changed, and the movie follows Lucy's progress as she adjusts to her new circumstances, including her husband's marriage to her best friend (Sela Ward), her fledgling love affair with the emergency-room doctor (Gabriel Byrne) who tried to save her life, and, once the story gets out, her new-found celebrity. All of this is presented with a broad-stroked, sitcom raucousness that's pretty tough to stomach. The movie is a Disney production, and it has that special brand of Tony brazenness -- the new Disney touch -- that a lot of its recent films have had. (If things keep up like this, Tinkerbell will have to exchange her wand for a sledgehammer.) There are some smart lines, but the scenes have no shape, and more often than not they're resolved by having Lucy knock something over. Somebody once said -- I think it was Plato -- that comedy isn't pretty, and "Hello Again" is absolute proof of that.

By Desson Howe

Washington Post Staff Writer

September 17, 1993

To 12-year-old Tito and his 8-year-old brother Ossie, the white horse called Tir na nOg is not of this world. The beautiful steed, given to them by their gypsy grandfather, is the finest, most beautiful thing in their lives. So when Tir na nOg (whose Celtic name means The Land of Eternal Youth) is apprehended by a police officer with black-market intentions, it's time for the Dublin lads to rescue their beloved and kindred spirit. "Into the West," which stars Gabriel Byrne as the boys' down-and-depressed father, and Ellen Barkin (as a gypsy who helps Byrne pursue his on-the-lam children), is a charming children's crusade -- a rewarding journey for all ages. Scriptwriter Jim ("My Left Foot") Sheridan and director Mike Newell (who did "Enchanted April") follow the boys' quixotic mission with an acute eye for the drab depression of Dublin's low-income apartment towers, the beautiful countryside beyond it and the hermetic, lore-driven world of the "travelers," a Celtic-originated gypsy tribe. Stuck in a rat-infested flat, Tito and Ossie are forced to abide the drunken, grieving gloom of their recently widowed father, Papa Riley (Byrne). To the boys, the arrival of Tir na nOg is the promise of better things. They listen, enrapt, as their grandfather (David Kelly) recounts the story of the Land of Eternal Youth, the mythical place under the sea where their horse comes from. But to their besotted father, who has rejected his traveler roots, Tir na nOg is just another maintenance problem. When an unscrupulous horse breeder (John Kavanagh) and a conspiring police chief take the horse away, Papa Riley only half-heartedly attempts to retrieve him. Appalled, the boys take matters into their own hands. The result is a sort of Celtic junior version of "Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid," as Tito and Ossie abscond with the horse, hide him under bridges and ride into the sunset, with the authorities -- and their contrite dad -- hot on their heels. They're headed for the west coast, where they intend to help Tir na nOg return to his mythic home under the sea. Spiritually rejuvenated by a reunion with the travelers, Papa Reilly realizes that -- should he find his children -- it's imperative to help them. Despite its twinkle eyed intentions, "Into the West" avoids the cloying, Disneyesque route. This is not a slapstick chase movie full of precious moments between a boy and his horse. The boys' dirty-faced ordeal is a very real, dangerous one, and their naive faith is the only defense against oppressive surroundings. Most of the emotional impact comes from the mutual presence of child actors Ciaran (pronounced "Keeran") Fitzgerald as Ossie, and Ruaidhri ("Rory") Conroy as Tito. With their pluckiness and perky brogue, they make two of the most memorable scalawags to scuffle across the screen in a long time. You can hear their chirrupy voices long after the movie is over.

By Roger Ebert

If I were to tell you that "Into the West" was about two boys

and their magical white horse, you would of course think it was a

children's film. But it is more than that, although children will

enjoy it. The movie is set in a world a little too gritty for

innocent animal tales. It concerns two young gypsy boys growing up in

the high-rise slums of Dublin, with their father, who loves them but

has grown distant and drunken since their mother died.

One day their grandfather, who still travels the roads in

the ancient way in his horse-drawn gypsy caravan, gives them the gift

of a horse. The horse is named Tir na nOg, which means "Land of

Eternal Youth," the grandfather explains, although he may be making

it up as he goes along. Where are two city boys to keep a horse? In

their apartment? Of course! But of course the neighbors complain, and

the police are called, and one thing leads to another.

Then the horse is stolen by a rich man, who obtains spurious

papers for it. The boys see it on television, go to where it is

racing, and ride off with it. The rich man offers a $10,000 reward,

and all of Ireland follows the story as the two boys and their horse

outwit the combined efforts of the rich and powerful.

The subtext of the movie involves the gypsy culture in

modern Ireland. Known also as tinkers and travelers, the gypsies are

often discriminated against, and charged with any crimes that take

place even vaguely near to them. For their grandfather (David Kelly),

the traveling life is still rich and satisfying, but for their father

(Gabriel Byrne), it has been replaced by a form of imprisonment in a

high-rise ghetto. The father enlists two friends (Ellen Barkin and

Colm Meaney), who remind him of the ancient strengths of the

travelers, and what is regained is not only a horse, but a family and

a tradition.

"Into the West" is one of many interesting films to come

from Ireland recently: Remember, for example, "My Left Foot," "Hear

My Song," "The Miracle," "The Commitments" and "The Crying Game." It

was written by Jim Sheridan, who wrote and directed "My Left Foot,"

and is directed by Mike Newell, who made "Dance with a Stranger" and

"Enchanted April." Sheridan and Newell are not interested in simply

shaping the material into an easy commercial form. They're interested

in the relationships beneath the surface, and in the way the father

is redeemed through the adventure.

And yet there is a lot of adventure, as the magnificent

horse seems almost able to read the boys' minds, and they think fast,

too, the older one (Ciaran Fitzgerald) guiding his younger brother

(Rory Conroy) as they avoid the main roads, ford streams to throw off

the bloodhounds, and at one point even escape certain capture by

taking a detour through the house of some strangers.

Texture is everything in a movie like this. The bare story

itself could be simplistic and silly: Cops chasing a couple of kids

on a horse. But when relationships are involved, and social

realities, and a certain level of magical realism, then the story

grows and deepens until it really involves us. Kids will probably

love this movie, but adults will get a lot more out of it.

By Roger Ebert

"Julia and Julia" tells one of those nightmare stories, like "The Trial," where the hero is condemned to live in a world in which absolutely nothing can be counted on. The story unfolds as a series of surprises, and since even the first surprise is crucial to the plot, I frankly don't see any way to review the film without spoiling some of the effect. I advise you not to read any further if you plan to be surprised by the film.

The story begins on the wedding day of its heroine, Julia, who is played by Kathleen Turner as a sweet and rather moony young woman not at all like the smart, aggressive characters she usually creates. It is a beautiful day in Italy, in a sunlit garden where even the trees seem to bow in happiness, but a few hours later Julia and her new husband (Gabriel Byrne) are involved in a road accident, and Byrne is killed.

Turner, an American, decides to stay in Italy. She moves into a small apartment across the street from the large flat that was to be her home. Time passes. One day something strange happens, which the movie shows but does not explain. She passes through some kind of dimension into a different time scheme, a parallel path in which things turned out differently and her husband did not die, and they have a small boy.

The sequence in which she discovers this is wonderful. She goes to her little flat, which is occupied by a strange woman who insists she has always lived there. She sees lights in the large flat across the street, which she had always refused to sell. Trembling, she climbs the stairs to find Byrne at home with their son and everyone treating her as if she had been with them all along and none of her tragic memories had ever taken place.

She is, of course, shattered. She does not know how this could have happened, and there is no one she can discuss it with, without appearing insane (although I kept wishing she wouldn't internalize everything). She is pathetically grateful to have her happiness back until one moment, completely without warning, she is plunged back into her other, tragic lifetime. Then she is flipped back to happiness again, sort of like a Ping-Pong ball of fate, and there is the complication of a lover (played by Sting), that she apparently has taken in her "happy" lifetime. (The rule at the center of these paradoxes is that she always remembers all of the sad lifetime, but only remembers those parts of the happy one that we actually see her experiencing.)

What's going on here? Don't ask me - and don't ask the movie, either. Even the simplest explanation, of parallel time tracks, is one I've borrowed out of old science-fiction novels. "Julia and Julia" wisely declines to offer any explanation at all, preferring to stay completely within Julia's nightmares as she experiences them.

The construction of the story is ingenious and perverse and has a kind of inner logic of its own. And if there is a flaw, it's that no woman could endure this kind of round trip more than once, if that much, before being emotionally shattered. I was reminded of Turner's work in "Peggy Sue Got Married," in which she traveled back in time to her own adolescence; think how much more disturbing it would be to travel sideways into the happiness you thought you'd lost.

By Rita Kempley

Washington Post Staff Writer

February 05, 1988

Kathleen Turner can't resist those other dimensions. Now she's gone and fallen into another one in the peculiar Italian-made "Julia and Julia" -- in which the former Peggy Sue gets married again, this time to a debonair architect from Trieste. Then before you can say Rod Serling, she's time-tripping (or slipping her gears) in the Zoni di Twilightoni. Here, Rod's spirit meets Italian neorealism as, for reasons beyond our comprehension, the heroine wobbles between two worlds. In the first, Julia is a widowed travel agent, still grieving for her husband Paolo (Gabriel Byrne), who was killed in a car crash during their honeymoon. "I am happy. I want to have a baby," she had just said. Six years later, she drives through a tunnel of fog to a new dimension where her husband is alive and they have a 6-year-old son. Julia is ecstatic, though she has a difficult time chatting with best friends she has never met. Controlling the portal between the two planes is a Jekyll-and-Hyde photographer, Daniel, played enigmatically by Sting. As the plot progresses, Julia shuttles willy-nilly between Door Number One and Door Number Two. One minute she's booking cruises, the next she's cheating on her husband -- an affair her "other self" had kindled -- with Daniel. When she tries to end it, the furious photographer rips off her underpants and rapes her behind a pillar in a busy piazza. Naturally, she just melts. Julia attempts to save her marriage in the other reality, and things take a nasty Gothic turn. Apparently Turner did some pasta-packing -- she's all plumped up for a part that calls for topless romping with both Byrne (wasted as droopy Paolo) and Sting. The unstable Julia must have seemed like a juicy opportunity for Turner, who likes to test herself with diverse roles -- like the prostitute in "Crimes of Passion" or the hit woman in "Prizzi's Honor." But Julia is no snake-pit psycho from the outer limits. She's a portly matron who gets a little mixed up in a beautiful, nicely photographed setting. Backed by an Italian television network, the feature is the first ever shot in "high-definition video," which means riper color and enlarged pores. Director Peter Del Monte and cinematographer Giuseppe Rotunno, both students of Roberto Rossellini, create an authentic ambiance with marble busts and lots of plaster dust. We don't get goose bumps, we feel as if we have to sneeze and can't.

The Keep

Here we suffer from the "why make movies out of books if we are going to make them bad" syndrome that Rees covers so eloquently in his review of "Phantoms". I loved the novel as it was creepy and had a lot of depth. The movie lacks both. I thought that this was a sure thing as it is directed by Michael Mann ("Heat", "Manhunter") and stars Scott Glenn ("Backdraft"), Jurgen Prochnow ("Das Boot"), Gabriel Byrne ("The Usual Suspects"), Ian Mc Kellen, and Robert Prosky. Boy, was I sadly mistaken. A one sentence plot summary is that the Nazis are ordered to take control of a keep and when men begin to die, they bring in a Jewish professor to try and figure out why. The acting is way below what is expected from these actors and I was very disillusioned when I found out that Michael Mann both wrote and directed this. I was expecting so much more... read the book instead.

It's amazing how fast people forget what it was like to

be 17 or 18: the intense feelings; the fear that every little slip will be your downfall;

the incredible emotional ups and downs. Those of us who have been through all this soon

discount what we see in those experiencing it now. We know most people get through this

time. We know things tend to level off. And maybe some of us become just slightly bitter

that the passion of that age doesn't last.

Frankie Griffin (Jared Leto) is right in the middle of what's often discounted by the rest

of us as 'teenage angst'. He's just finished high school, and as he awaits what he expects

to be disastrous exam results, he also pines for a couple of seemingly unattainable young

women. His summer in Ireland is spent hanging out with his nerdy friends and his eccentric

family, admiring his love interests from afar, and counting the days until the dreaded

exam results arrive.

Leto plays Frankie in an understated and convincing manner. Some of the supporting cast

members are equally successful, although the big name actors who play his parents (Gabriel

Byrne and Catherine O'Hara) aren't nearly as believable. O'Hara plays a wacky

anti-English, anti-Protestant Irish nationalist, and she succeeds mainly in being

irritating. Byrne's appearances in the film are insignificant. Perhaps he was too busy

serving as co-writer (adapting the story from Ferdia MacAnna's novel) and co-executive

producer to create a meaningful character for himself.

In the end, we are left with Frankie Griffin, his fears and aspirations. And we're left

with the unattainable Romy (nicely played by Emily Mortimer). For some, this won't be

enough to make Summer Fling worthwhile. It just doesn't have enough substance. But for

those who can still feel echoes of their own 'teenage angst', this film rings true.

By Roger Ebert

The very title summons up preconceptions of treacle do-gooders in a

smarmy children's story, and some of the early shots in "Little

Women" do little to discourage them: In one of the first frames, the

four little women and their mother manage to arrange their heads

within the frame with all of the spontaneity of a Kodak ad.

But this is movie is not smarmy, not do Gooding, and only a

little treacle; before long I was beginning to remember, from many

years ago, that Louisa May Alcott's Little Women was a really good

novel - one that I read with great attention.

Of course, I was 11 or 12 then, but the novel seems to have grown

up in the meantime - or maybe director Gillian Armstrong finds the

serious themes and refuses to simplify the story into a "family"

formula. "Little Women" may be marketed for children and teenagers,

but my hunch is it will be best appreciated by their parents. It's a

film about how all of life seems to stretch ahead of us when we're

young, and how, through a series of choices, we narrow our destiny.

The story is set in Concord, Mass., and begins in 1862, in a

winter when all news is dominated by the Civil War. The March family

is on its own; their father has gone off to war. Times are hard,

although it's hard not to smile when we find out how hard: "Firewood

and lamp oil were scarce," we hear, while seeing the Marches living

in what passes for poverty: a three-story colonial, decorated for a

Currier and Ives print, with the cheerful family cook in the kitchen

and the Marches sitting around the fire, knitting sweaters and

rolling bandages.

The movie doesn't go the usual route of supplying broad,

obvious "establishing" scenes for each of the girls; instead, we

gradually get to know them, we sense their personalities, and we see

how they relate to one another. The most forcible personality in the

family is the tomboy daughter Jo, played in a strong and sunny

performance by Winona Ryder. She wants to be a writer, and stages

family theatricals in which everyone - even the long-suffering cat -

is expected to play a role.

The others include wise Meg (Trini Alvarado) as the oldest;

winsome Amy (Kirsten Dunst) as the youngest, and Beth, poor little

Beth (Claire Danes), as the sickly one who survives a medical crisis

but is much weakened ("Fetch some vinegar water and rags! We'll draw

the fever down from her head!"). There isn't a lot of overt action

in their lives, but then that's typical of the 19th century novel

about women, which essentially shows them sitting endlessly in

parlors, holding deep conversations about their hopes, their beliefs,

their dreams and, mostly, their marriage destinies.

The March girls have many other interests (their mother, played

by Susan Sarandon, is what passed 130 years ago for a feminist), but

young men and eligible bachelors rank high on the list. Their young

neighbor is Laurie (Christian Bale), a playmate who is allowed to

join their amateur theatricals as an honorary brother, and who

eventually falls in love with Jo. Then there's Laurie's tutor, the

pleasant Mr. Brooke (Eric Stoltz), who is much taken with Meg, but is

dismissed by Jo as "dull as powder."

Jo, who moves to New York and starts to write lurid

Victorian melodramas with titles like The Sinner's Corpse, falls

under the eye of a European scholar, Friedrich Bhaer (Gabriel Byrne),

who takes her seriously enough to criticize her work. He knows she

can do better - why, she could write a novel named Little Women if

she put half a mind to it. "I'm hopelessly flawed," Jo sighs.

But she is not. And late in the film, when she tells Friedrich

that, yes, it's all right for him to love her, Ryder's face lights up

with a smile so joyful it illuminates the theater.

"Little Women" grew on me. At first, I was grumpy, thinking

it was going to be too sweet and devout. Gradually, I saw that

Gillian Armstrong (whose credits include "My Brilliant Career" and

"High Tide") was taking it seriously. And then I began to appreciate

the ensemble acting, with the five actresses creating the warmth and

familiarity of a real family.

The buried issues in the story are quite modern: How must a

woman negotiate the right path between society's notions of marriage

and household, and her own dreams of doing something really special,

all on her own?

One day, their mother tells them: "If you feel your value lies

only in being merely decorative, I fear that someday you might find

yourself believing that's all you really are. Time erodes all such

beauty, but what it cannot diminish is the wonderful workings of your

mind." Quite so.

The title alone suggests demureness and docility, two characteristics which were absolutely antithetical to its author, Louisa May Alcott, a strong woman of the nineteenth century who was determined to make her living, not as a servant or as a seamstress, but as a writer. It has been reported that the author found "Little Women" a bore to write and that the values in the book belong to her educator father and not to herself, but she did achieve her dream of making her living as a writer. In the latest version of "Little Women", dedicated to the memory of Polly Klaas, Winona Ryder makes a delightful Jo March for 90's audiences & she is well supported by Gabriel Byrne in one of his best performances as Professor Bhaer. Meg, Beth and Amy are effectively played by Trini Alvarado, Claire Danes and Samantha Mathis, although Kirsten Dunst, so good as Claudia in "Interview With The Vampire", is the most adorable of the bunch as twelve-year-old Amy March. (Alas, a great scene in which she is abused by a schoolmaster apparently wound up on the cutting room floor, although it made the cut in precious movies and is referred to here. Maybe we'll get to see it in the restored video release. This is one 110 minute movie I wouldn't have minded being 10 minutes longer.) Christain Bale is the best Laurie ever cast in the role and it's a treat to see Mary Wickes, now 82, still slugging out those lines as Aunt March 53 years after her feisty debut in "The Man Who Came To Dinner". As for the rest of the characters, well, here is where you miss the Oscar-winning 1933 screenplay by Sarah Y. Mason and Victor Heernan. Robin Swicord's new script has some wonderful stuff in it and recreates favourite sequences from the original novel unrecorded on film before. But every so often, especially in the case of Susan Sarandon's character as Marmee, it slips into revisionist dialogue clearly calculated for late twentieth century ears. Certainly Louisa May Alcott's family was a progressive family, but for its era, not our own. There is plenty of material in her book that expresses nineteenth century feminism in far more convincing terms than Swicord's anachronistic departures. Mr. March, a key figure in the book and previous versions, is reduced to a walk-on here, Eric Stoltz is wasted as Meg's love John Brooke and Mr. Laurence, an extremely critical character, is sketchily developed and badly cast. (The multifaceted Sir Alec Guiness would have been a better choice than an iceberg like John Neville.) Gillian Armstrong's obvious affection for the material gives a special glow to the girls' homemade theatrical entertainments and their romps in the snow with Laurie. After seeing her altogether worthy successor to George Cukor's "Little Women", you may want to check out the 1933 movie on video.

Mad Dog Time (Trigger Happy)

(1)

In Vic's world, power is the name of the game, and the

rules of the game change with every move. To win, you need brains, style and a fast

trigger finger. In Vic's world, you live life to the fullest...because you never know when

your number's up.

A sleek black comedy, MAD DOG TIME features an all-star cast, including (in alphabetical

order) Ellen Barkin, Gabriel Byrne, Richard Dreyfuss, Jeff Goldblum, Gregory Hines and

Diane Lane. Inspired by the spirit and the cool of the infamous "Rat Pack," the

film is written and directed by Larry Bishop, whose father, comedian Joey Bishop, was a

member of "The Clan."

Boss of bosses, Vic (RICHARD DREYFUSS), is crazy--certifiably--and has been locked up in a

mental ward for a spell. In his absence, friends, enemies and cronies have been jockeying

for power and position. But now comes the news that they've all been dreading: Vic is

getting out.

Returning to find his empire in chaos, Vic seems to want simply to "get the balance

back." He knows it's gonna be murder to set things right...he's just not sure whose.

Mickey Holliday (JEFF GOLDBLUM) has the most reason to worry, but you'd never know it. The

image of panache, Mickey is Vic's trigger man, the fastest gun in a new-style showdown

that is more civilized than those of the Old West, but just as deadly. His only weakness

is women, and it just may be the death of him because he's been two-timing a pair of very

dangerous dames: Vic's girlfriend Grace (DIANE LANE) and her murderous-when-crossed sister

Rita (ELLEN BARKIN).

Then there's Ben London (GABRIEL BYRNE), Vic's right-hand man, who appears to have been

cleaning things up in preparation for Vic's homecoming--executing a few pink slips, so to

speak. He actually has plenty to worry about, but his mouth is running ahead of his brain

and he hasn't quite caught on to that yet. Ben wants things his way for a change and

thinks the time has come for him to get his due. Vic is just the man to give it to him.

Smelling weakness, rival gangster Jake Parker (KYLE MacLACHLAN) may be the only one truly

glad to see Vic get out and has the perfect homecoming gift for him: a formal

straightjacket. The way Jake figures it, Vic will kill Mick and Ben will kill Vic, or Mick

will kill Vic and Ben will kill Mick...or whatever. Either way, Jake comes out on top.

Just in case though, he's brought in a mysterious new triggerman (CHRISTOPHER JONES),

rumored to be faster than Mick, deadlier than Vic and his name is Nick, which should make

him fit right in. But what Jake doesn't know about Nick just might kill him.

What Jake does know is that Mickey and Vic may be too smart to play along with his little

game. To ensure that things are set in motion, he has his new triggerman kill Mickey's

friend and manager Jules Flamingo (GREGORY HINES).

The body count rises as debts are paid and bets are covered. It soon becomes apparent that

the only thing crazy about Vic is underestimating him.

United Artists Pictures presents a Dreyfuss/James Production, in association with Skylight

Films, of a Larry Bishop Film, MAD DOG TIME, starring in alphabetical order Ellen Barkin,

Gabriel Byrne, Richard Dreyfuss, Jeff Goldblum and Diane Lane. The film also stars Larry

Bishop, Gregory Hines, Kyle MacLachlan and Burt Reynolds, with cameo appearances by Rob

Reiner, Richard Pryor, Paul Anka, Billy Idol, Angie Everhart, Christopher Jones, Henry

Silva and Joey Bishop. MAD DOG TIME was written and directed by Larry Bishop and produced

by Judith Rutherford James, with Stephan Manpearl and Leonard Shapiro executive producing.

MAD DOG TIME (TRIGGER HAPPY) (2)***

Starring Jeff Goldblum, Richard Dreyfuss, Gabriel Byrne, Ellen Barkin and Larry

Bishop. Directed and written by Larry Bishop. Produced by Judith Rutherford James. A UA

release. Comedy. Rated R for violence, language and sexuality. Running time: 93 min.

The actor credit scroll for this UA pickup could really have

been prefaced "in order of disappearance." Key characters are killed off so fast

in "Mad Dog Time" that an audience can be forgiven for wondering who (if anyone)

is going to be left onscreen by movie's end. Offbeat humor spliced with full-face shots

and slow motion coupled with a high-caliber cast make Larry Bishop's writing/directing

debut worthy of the ticket price. As an added bonus, Bishop's friends come to his aid by

way of cameos; among those momentary and varied players are Richard Pryor, Rob Reiner and

Paul Anka. The film also pays homage to the original Rat Pack (of which Bishop's father,

Joey Bishop, was a member) by including in its jazzy soundtrack tunes from Frank Sinatra,

Dean Martin and Sammy Davis Jr.

After a lengthy stay at a mental hospital, mobster Vic (Richard

Dreyfuss) is being released. In his absence, "Brass Balls" London (Gabriel

Byrne) has taken over control of the operation. Now, though, it's time for Vic not only to

reconcile differences with his wife (Ellen Barkin) but to act like a mad dog and reclaim

control of his empire. Vic's rivals can walk, hop or crawl away peacefully, but

challenging him could prove to be fatal.

Bishop succeeds in creating a timeless period movie; the audience is

transported to a place and time that might be called Vic's World. There are resemblances

to the prohibition era, but the accents are those of contemporary technology. Patrons

might not fully understand what they just watched--"Mad Dog Time" straddles the

borderlines of the art-house and mainstream--but most should agree it's enjoyable. Holding

the enterprise together are the suspense, tension and cunning humor supplied by Vic's

right-hand man, Mickey Holliday (Jeff Goldblum). Goldblum fans are sure to have a fun time

watching their favorite quirky actor turn into a suave--and forehead-shooting--playboy.

-Dwayne E. Leslie

The Man in the Iron Mask (1)

THE MAN IN THE IRON MASK (2)

Leonardo DiCaprio cements his position as one of young Hollywood’s top draws as the title character in "The Man in the Iron Mask". Based on the novel by Alexandre Dumas père and set in the 17th century, the film tells the story of a king whose tyrannical disposition prompts those in his service to replace him with a almost-unknown twin brother. This sort of swashbuckling costume drama has been missing from theaters for too long. It returns now with gusto. With a new generation of musketeers defending the king of France (Leonardo DiCaprio), the glory days of Aramis (Jeremy Irons), Athos (John Malkovich), Porthos (Gérard Depardieu), and D'Artagnan (Gabriel Byrne) are but a revered memory. Aramis has become a priest and is an advisor to the king while Athos is content to be the proud father of a son (Peter Sarsgaard) who wants to follow in his footsteps. Porthos, although prone to bouts of life-questioning depression, is still as randy as ever, while D'Artagnan is now captain of the musketeers. These old friends don’t get together as much as they did in the past, but each knows he can depend on the others when a mission of importance comes his way. One such mission is self-imposed when the king’s cavalier disregard for his people results in rioting in Paris. Porthos joins Aramis unquestioningly in his plan to replace the king, but Athos buys into it because the king has recently wronged him. D'Artagnan, who believes his duty to the king is absolute, is alone in refusing to participate. Nevertheless, the plan is executed without his direct knowledge. This leads to a crisis of conscience when he finds himself pitted against the three musketeers of renown by the order of the king. With the inestimable acting talents of its first- rate cast and a script that allows for action, emotion, and humor in proper proportion, "The Man in the Iron Mask" is a far cry from the smarmy "Three Musketeers" movie released a few years ago by Disney. Irons, Byrne and Malkovich are at the top of their form in this engrossing period piece, but Depardieu deserves special mention for his particularly vivacious performance. Ironically, it is heartthrob DiCaprio who fares the worst among the leads, but not by any fault of his own. As the evil king and his saintly brother, he has been bound by the largely two-dimensional nature of both characters. To his credit, DiCaprio is able to infuse each with a degree of potency not possible by many of his peers. Despite its title, this film is really about the friendship of the four musketeers and their devotion to the ideal of justice. If you ignore the unfitting voice-over at the conclusion, what remains is a rousing adventure that embraces best aspects of humanity. If you have been waiting for the next great reason to part with your money at the box office, "The Man in the Iron Mask" will end your wait with a flourish.

By Roger Ebert

By Desson Howe

Washington Post Staff Writer

October 05, 1990