| Pike Cichlids of the Lugubris Group |

|---|

Vinny Kutty

| Pikes of the Lugubris group are the largest members of the genus, with tiny scales and a very smooth, salami-like appearance. They require very large tanks but are certainly the most colorful members of the genus. |

Pikes belonging to the lugubris group (or the strigata -type) are the largest members of the 110 (and counting) species of Crenicichla, often reaching sizes up to 18 inches. Some females reach only a foot and Jeff Cardwell (pers. comm.) reports having observed a pair of undescribed Xingu species reaching almost 2 feet in length. There exists an undescribed species from Venezuela (C. sp. Venezuela) at the Steinhart Aquarium in San Francisco that is easily two feet in length. Both Crenicichla lugubris Heckel, 1840 and C. strigata Gunther, 1862 are valid species of Crenicichla, but have simply been chosen as representatives of their group, as they exhibit the group s general traits. Their distinguishing characteristics are a high number of spines and scales along the lateral line. Their tiny scales and their elongated shape give them a Salami-like appearance.

In 1991, Ploeg included 13 species in this group based on their size (up to 300 mm SL) and a large number of scales along the side of the fish (more than 82). Other groups of Crenicichla possess fewer than 80 scales. I do not rely on scale counts for identification for practical reasons and so, coloration and collection locality is of more value.

Ploeg s 13 species:

C. johanna Heckel, 1840

C. jegui Ploeg, 1986

C. ternetzi Norman, 1926

C. vittata Heckel, 1840

C. acutirostris Gunther, 1862

C. tigrina Ploeg et al., 1991

C. multispinosa Pellegrin, 1904

C. cincta Regan, 1905

C. lugubris Heckel, 1840

C. adspersa Heckel, 1840

C. lenticulata Heckel, 1840

C. strigata Gunther, 1862

C. marmorata Pellegrin, 1904

Kullander (1997) further elaborated on the theme in his paper where he described another lugubris-group member, namely C. rosemariae. In his paper, he split Ploeg s 13 into two groups. One with pointy snouts and the other with blunt snouts. The blunt-nosed, robust-bodied Pikes now are still in the lugubris-group, but the pointy. More slender ones are now in a new group of their own: the acutirostris group. The pointy-nosed fish generally have smaller scales. This distinction may not necessarily mean that members of either group are closely related. The Guyanan C. ternetzi and C. multispinosa may be closely related but their relationship to substantially different species such as C. jegui has yet to be clearly understood.

Kullander s acutirostris-group:

C. jegui Ploeg, 1986

C. ternetzi Norman, 1926

C. vittata Heckel, 1840

C. acutirostris Gunther, 1862

C. tigrina Ploeg et al., 1991

C. multispinosa Pellegrin, 1904

C. phaiospilus Kullander 1991

Perhaps Ploeg implicitly intended this split as well, as the sequence of the list above is the same as it is in his key to the lugubris-group on page 61 of his dissertation, except for C. phaiospilus, since it was described by Kullander in 1991.

Kullander s lugubris-group:

C. cincta Regan, 1905

C. lugubris Heckel, 1840

C. adspersa Heckel, 1840

C. lenticulata Heckel, 1840

C. strigata Gunther, 1862

C. marmorata Pellegrin, 1904

C. johanna Heckel, 1840

C. rosemariae Kullander, 1997

C. ornata, according to Ploeg (1991) is actually juvenile C. lenticulata.

Until the recent interest in the Loricariid catfish from Rio Xingu, the habitat of a few attractive Pikes, importation of large Pikes was rare. The occasional lugubris-group member that came in was immediately labeled Black Line Pikes or C. strigata. This is usually the very large, robust and rather drab fish from Venezuela. It so happens that the true C. strigata is not found in Venezuela, but over a thousand miles away in the Tocantins and Capim river systems. Unlike its Venezuelan counterpart, the true C. strigata has a clearly ocellated humeral blotch (ringed shoulder-spot) behind its gill cover (Warzel, 1991.) The humeral blotch in the Venezuelan species is often faded and almost absent. So, the hobby strigata is an undescribed species and still goes by the wrong name even today (See Page 92 of the November 1997 issue of TFH magazine.)

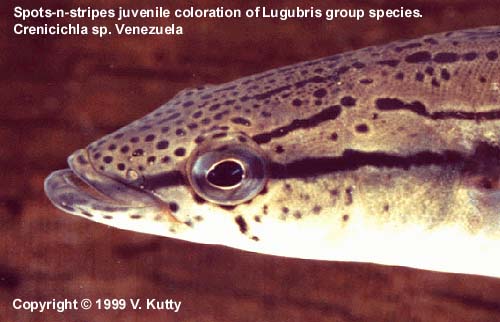

Many of them find their way into the aquarium hobby as cute juveniles. They are often quite colorful - brownish red to bright orange, with a distinctive pattern of spots and stripes. There are numerous spots on the head and the body has a few horizontal black stripes or bands, hence their common name of Black Line Pikes. They are small when imported, schooling tightly, they show no signs of aggression. The combination of "friendly" deportment and general cuteness gets them taken home by aquarists who are usually unaware of the potential size of these fish. They are active and quickly associate humans with food; this leads to constant begging and consequent feeding. Being ravenous eaters, you often see juveniles with lumpy stomachs, after having overfed. Most of the food is put to good use as they can grow at incredible rates. Some specimens can actually reach a foot long in the first year of life.

Many of them find their way into the aquarium hobby as cute juveniles. They are often quite colorful - brownish red to bright orange, with a distinctive pattern of spots and stripes. There are numerous spots on the head and the body has a few horizontal black stripes or bands, hence their common name of Black Line Pikes. They are small when imported, schooling tightly, they show no signs of aggression. The combination of "friendly" deportment and general cuteness gets them taken home by aquarists who are usually unaware of the potential size of these fish. They are active and quickly associate humans with food; this leads to constant begging and consequent feeding. Being ravenous eaters, you often see juveniles with lumpy stomachs, after having overfed. Most of the food is put to good use as they can grow at incredible rates. Some specimens can actually reach a foot long in the first year of life.

PIKE CICHLIDS |

Their cuteness gets them taken home by aquarists who are often unaware of the potential size of these fish. |

While many of the adults turn into swans as they age, this group of Pikes is especially susceptible to neuromast erosion or hole-in-the-head syndrome. Many adults have this problem and it is usually a result of poor water condition. Some hobbyists have tried to maintain very low nitrogen levels in the water by conducting large water changes and employing heavy filtration, still to have their Pikes develop this non-lethal problem. Some hobbyists claim that charcoal filtration and the resulting removal of some unidentified mineral or organic compound cause it. If your water is deficient in some mineral or some organic complex, you may be able to compensate by feeding a varied diet and supplying the missing mineral through the food. A C. johanna under my care developed this problem while being fed only pellets and the situation stopped getting worse after various frozen and live foods were introduced into the diet. Of course, once the holes have spread, they seldom heal. The condition does not appear to hinder the fish from going about its usual activities. It certainly doesn t suppress the victim s appetite.

PIKE CICHLIDS |

PVC tubes may be unaesthetic but it is quite effective in keeping increasingly aggressive sub-adult fish from destroying each other - pikes subscribe to the out-of-sight-out-of-mind philosophy. |

Sexing these fish is easy if they are adults. The females have a thin white band just under the outer edge of the dorsal fin (submarginal band)and a pink belly while the males lack these features and are generally a bit larger and less colorful. Unlike members of the saxatilis-group, these fish do not possess extended dorsal fin rays and cannot be reliably used to determine the sex.

Success in breeding these Pikes is very rare. The reason for this situation is usually a lack of effort. There are very few people who have remained with a group of these Pikes raising them from juveniles to adulthood and providing them with ample room, appropriate food and acceptable water quality to be rewarded with a spawn. To my knowledge, Wayne Leibel may be the first American and possibly the first person to have spawned a member of this group in aquaria. While spawning reports of saxatilis-group members are common, I only know of three species of the lugubris-group that have been successfully reproduced in captivity: C. marmorata (by Wayne Leibel and Frank Warzel), C. vittata (by Uwe Werner) and C. lugubris (by Frank Warzel.) A spawn from C. acutirostris was reported from Germany (Warzel, 1995) but there were no live fry. Frank also reports that his C. phaiospilus laid eggs but the eggs did not hatch. Ron Georgeone had a similar experience with C. sp. Xingu I. When spawning did occur, eggs were laid in caves, and the large eggs were attached to the side of the cave by filamentous stalks (Leibel, 1992.) The eggs sway in he water current, since they are not firmly fixed to the surface.

While the fry-rearing behavior of members of the saxatilis-group pikes (Spangled pikes) provides few surprises to breeders of neotropical cichlids, lugubris-group pikes are full of surprises. The eggs have a lengthy development stage; Leibel (1992) reports that the fry were not free swimming for seven days post hatching. They allow their fry to contact feed and even open their mouths wide for the fry to enter and investigate/search for food! The high interjuvenile tolerance is an indication of the length of parental care provided. It is likely that parental care ceases when the juveniles cannot stand to be near each other. Generalization regarding the number of eggs cannot be made since we have only a handful of recorded spawns. As with all cichlids, the number of eggs is highly dependent on the condition of the female.

Wayne writes that the spawning conditions were neutral pH, soft water and a temperature of 78°F. This is certainly less extreme and easier to duplicate than some of the water values I have seen lugubris-types living in: pH of 5.4 and near-distilled hardness and temperatures in the mid 80s °F. He reports that the fry became free swimming after 12 days (5 days to hatch and 7 more to swim.) Of course, higher temperatures will quicken the development of the fry. Wayne's successs is not just a result of luck; upon reading his spawning report, one comes to the conclusion that the tank was very heavily filtered and aerated and the fish were provided numerous spawning sites in the form of gnarled driftwood and an unlimited supply of feeder goldfish.

Pike cichlid diseases? Well, I can t help you I ve never had a sick Pike! Perhaps I ve been lucky but these are certainly tough characters. If given clean water and a good variety of foods, they are capable of warding off illness quite well. Graham Ash of UK claims to be able to reverse hole-in-the-head disease by placing the fish in a stress-free environment at a temp of 90°F and treating for Hexamita with Metronidazole. My attempts to do this, following Graham's technique, arrested the progression of the problem but it did not reverse the disease or heal the holes.

Their behavior in the wild is not well known but the picture is becoming increasingly clear. Reports from hobbyists who have snorkeled in Rio Xingu are that some of the larger lugubris-group members in that river protect their fry until they are almost six inches long and well into their juvenile stage. Adults in the wild appear to be mostly solitary, until it s time to breed. My observations on C. lugubris in the Rio Uatuma are that they live in still water in riverside lakes and pools. The visibility in the water was fairly murky and as a result, snorkeling would not have revealed much. My friend, Jeff Cardwell caught them using a small hook and line. On another trip to the Peruvian Amazon, I was able to observe Crenicichla cincta in two different habitats - calm lakes and a swift-flowing stream. In both cases, the water was near neutral and soft (pH 7.2 and 90uS conductivity). The water in the lake was warmer at about 83°F and the stream was at 78°F. The stream had little in the way of cover or hiding places, but it was only a few yards from the main channel of the Amazon River and it could have been seeking shelter from large catfish. The lake had a muddy bottom littered with dead leaves, tree stems and twigs. C. cincta is found along the entire length of the Amazon, from Iquitos to Belem, and I would expect to find it in various habitats and water conditions.

Identification Guide for the Crenicichla lugubris group

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPECIES | LOCALITY | HEAD MARKING | HUMERAL BLOTCH | CAUDAL SPOT | OTHER MARKING | BODY SHAPE |

| acutirostris | Tapajos | Absent | Absent | Very small | Black bars on back | Very slender |

| adspersa | Guapore | Present | Roundish unocellated | Small, roundish | Absent | Very robust |

| cincta | Amazon, Solimoes | Absent | Continuos with lateral band | Large, round, ocellated | Black narrow bars | Robust |

| johanna | Amazonas, Orinoco, Guyana | Absent | Absent | Absent | Broad lateral band | Robust |

| lenticulata | Negro, Branco, Orinoco | Present | Large, irregular, ocellated | Irregular, ocellated | Large blotches on back | Very robust |

| lugubris | Amazon, Negro, Guyana | Absent | Large, unocellated | Roundish | Blotch behind eye | Robust |

| marmorata | Lower Amazon | Absent | Irregular, large, ocellated | Irregular, ocellated | Orange/black blotches | Very robust |

| multispinosa | Maroni | Absent | Absent | Small, ocellated | White spots in males | Very slender |

| percna | Xingu | Present | Absent | Absent | 3-5 black dots on flanks | Very slender |

| phaiospilus | Xingu | Absent | Absent | Absent | 5-7 black dots on flanks | Slender |

| rosemariae | Upper Xingu | Absent | Small, roundish, unocellated | Small, roundish | Small spots on body (males) | Robust |

| strigata | Tocantins, Capim | Absent | Large, roundish, ocellated | Irregular ocellated | Spots on caudal peduncle | Robust |

| ternetzi | Oyapoque | Absent | Absent | Absent | Prominent lateral band | Very slender |

| tigrina | Trombetas | Absent | Small, unocellated | Small, ocellated | Black dots and tiger-stripes on males | Very slender |

Identification Guide for the Crenicichla lugubris group

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPECIES | LOCALITY | HEAD MARKING | HUMERAL BLOTCH | CAUDAL SPOT | ADDITIONAL MARKING | BODY SHAPE |

| sp. Xingu I | Xingu | Absent | Absent | Roundish, ocellated | Absent | Slender |

| sp. Xingu II | Xingu | Absent | Large, unocellated | Roundish | Blotch behind eye | Slender |

| sp. Xingu III | Xingu | Absent | Small, longish, unocellated | Absent | An all-black fish! | Robust |

| sp. Atabapo | Atabapo | Absent | Small, unocellated | Absent | Black dots on caudal peduncle | Robust |

| sp. Tapajos | Tapajos | Absent | Small, unocellated | Roundish, ocellated | Absent | Robust |

| sp. Venezuela | Orinoco | Absent | Unocellated | Roundish, unocellated | Blotch behind eye | Very robust |

| sp. Madeira | Right bank of Madeira | Present | Irregular, slightly ocellated | Irregular, small, ocellated | Black pattern on back | Robust |

| sp. Trombetas | Trombetas, Curua | Absent | Large, unocellated | Not detectable | Large black bars | Very robust |

| sp. Arapiuns | Arapiuns, Lower Tapajos | Absent | Irregular, ocellated | Irregular, small, ocellated | Irregular lateral band | Robust |

| sp. Cumina | Cumina | Absent | Small, unocellated | Very small, unocellated | Black dots on back (males) | Very slender |

| sp. Aripuana | Aripuana | Absent | Absent | Very small, ocellated | Small spots on upper operculum | Very slender |

Thanks to Mike Jacobs, Jessica Milller, and Gustavo Alcides Concheiro P鲥z for helping me figure out how to make tables using HTML codes. Also, special thanks to Frank Warzel for helping me fill in the blanks in this table.

| Back to ==> Home / Pike Cichlid Articles / Lugubris Group Pikes |

| Home | Pikes | Neotropicals | Collecting | Photography | Personal | Links | Site map |

|

http://geocities.datacellar.net/NapaValley/5491

Latest update: 13 December 1999 Comments on this page: email me at kutty at earthlink dot net |