|

|

By Vin Kutty

|

|

In the Fall of 1992, Carlos Lucena and Sven Kullander published a paper titled ‘The Crenicichla species of the Uruguai River drainage in Brazil’, where they recognized eleven species of pike cichlids in the Brazilian portion of the Rio Uruguay. Of the eleven species discussed, seven were newly described species found only in the Rio Uruguay drainage.

Rio Uruguay is a major tributary of the Rio de la Plata, starting its 1000-mile length in southern Brazil. It then forms the border of Brazil and Argentina in its middle course and finally, the border between Argentina and Uruguay in its lower course.

As I read the Lucena and Kullander paper, I was amazed and impressed that a subtropical river would have so many endemic species. I decided then that I would someday travel to Rio Uruguay in search of these pike cichlids. Since most of these new species were found in the Brazilian State of Santa Catarina and Rio Grande do Sul, a trip to southern Brazil was required. Unfortunately, with the recent hyper-enforcement of Brazilian laws restricting collecting and exporting native flora and fauna, another plan was called for. To get a fair understanding of these fishes’ habitat, more than one trip would be required.

Since my dear friend Marcelo Casacuberta of Montevideo, Uruguay is an aquarist and a close friend of Felipe Cantera, the only authorized collector and exporter of fishes from Uruguay; I requested their help in my endeavor. So, in March 2001, toward the end of the Southern Summer, fellow Californians, Nathan Okawa and Jim Herman joined me in going to Uruguay.

Uruguay is an oft-overlooked nation in a continent where Brazil, Argentina and Colombia garner most of the attention. The capitol of Uruguay, Montevideo is 34°South, which is as far south of the equator as Atlanta and Los Angeles are north. The weather is very similar to that of North Florida and Georgia due to the latitude and presence of the Atlantic Ocean. This is clearly a subtropical country with two distinct seasons – a hot summer and a cool winter, with the nighttime air temperatures in July often hovering near freezing. When visiting this country, one would not expect to see any cichlids, with its seemingly endless rolling grasslands and relatively treeless biotope. But there are cichlids - so many cichlids for a country smaller than Pennsylvania! The roads (and the general human condition) are better than in most of Latin America, allowing fairly rapid access to the three or four distinct cichlid habitats.

Of the twenty or so cichlids encountered in the country, eight of them are pike cichlids of the genus Crenicichla. Of the eight, four are found only in Rio Uruguay (spelled Uruguai in Brazil). We expected to see Crenicichla lepidota, C. scotti, C. punctata and possibly C. vittata in the north if we were lucky - from experience, I have learned not to build in expectations of fascinating new cichlid discoveries when traveling to South America. A bit of news, however, piqued my anticipation and excitement before the trip - a couple of weeks before our departure, Felipe caught a new Crenicichla he’d never seen before. Apparently, neither had any of the local fishermen. The species looked like C. missioneira.

The day after arriving Montevideo, (via Lima, Peru, where at 3 AM, Nathan and I hit the duty free shops like mallrats to buy Incan trinkets we’d regretted not picking up in 1998, and Santiago, Chile) we made the 600-kilometer journey to the northern state of Salto, where the new pike was collected. Here, the mile-wide Rio Uruguay separates Salto from Argentina. This river’s bottom is littered with smooth, egg-sized ‘river rocks’, not sand or clay like I’d been used to. We spent a couple of evenings sitting chest deep in the river, staring at the sunset over Argentina.

Felipe had caught one adult C. missioneira near here in a lake connected to the river. Within minutes of our arrival, we began seining the location. We caught juvenile C. vittata, C. lepidota, Cichlasoma pusillum, Gymnogeophagus balzanii and the undescribed Gym. Sp. Salto, but no C. missioneira. Nathan’s superior cast-netting skills didn’t get us any new pikes either. After a couple of hours, I thought perhaps a storm had washed down a few C. missioneira from Brazil, as C. missioneira and the other Rio Uruguay endemics are all known only from Brazil, never this far south. After all, it gets pretty cold here in the southern winter. July 2001 saw nighttime air temperatures in Salto sink to 28°F for a few nights. Of course, we were there in early March and Felipe had recorded an afternoon temperature of 110°F just a couple of weeks earlier when he caught the lone C. missioneira.

We then disappointedly turned our attention to catching Gym. Balzanii adults, which were found only in chest deep (or deeper) water. On our initial deep-water seine, we were rewarded with our first C. missioneira. A juvenile, probably 3 or 4 months old. I then retracted my washed-down-from-Brazil theory. They were reproducing here! Unlike the main river channel, this habitat was muddy, warm and stagnant with the shorelines choked with aquatic plants. The water was soft but the pH varied over the course of a couple of days from 6.7 to 7.4, not unlike clear water rivers of the Amazon. The water temperature in the deeper areas was 85°F but near the shore, where the Cichlasoma and Gym. Sp. Salto proliferated, it was a warm 92°F. It is possible that C. missioneira occupy deeper waters to insulate themselves from temperature fluctuations typical to the ‘Mission’ districts of Uruguay and Brazil. We quickly scampered around, photographing the lone juvenile, as there were no known photographs of live specimen.

A few more deep water seines about 100 feet from shore and we had six juvenile C. missioneira. That was it – our efforts didn’t get us anymore in the next two days. However, we did catch some impressive, yellow-gold, high-bodied, Gym. Balzanii and an interesting, yellow-colored Piranha that reminded me of Serrasalmus ternetzi from Brazil. The sight of this intriguing chill-tolerant Piranha was apparently a rare occurrence until recently per the local fishermen. If accidentally introduced to the southern or coastal western United States, I’m afraid it and the pikes mentioned here could colonize local water bodies with little difficulty.

On our second day in Salto, we drove a few miles inland from the river, past groups of Ostrich-like Rhea americana, towards a one-street town named Espenillar. Along the way, we stopped at one of the hundreds of Arroyos (streams) that drain the country, to collect some Ancistrus sp. for Jim. The stream was lined with tall Eucalyptus trees housing flocks of angry Monk Parakeets protesting our presence. The shores had a lot of aquatic vegetation including Echinodorus sp. the size of a small car and a lot of other aquatic plants. The substrate consisted of pebbles and melon-sized rocks. Lifting up a rock and quickly placing a net underneath it often rewarded us with an undescribed black Ancistrus species with small white spots. The water was soft, neutral and flowing at a moderate pace. Seining here was difficult but Felipe attempted it a couple of times.

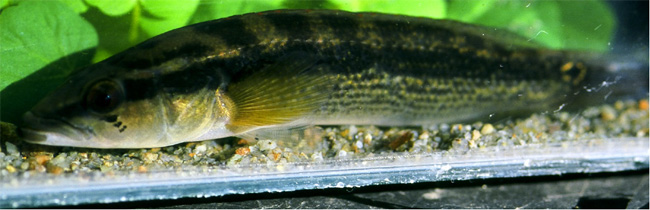

We caught one pike here. Felipe and I looked at it and thought to ourselves “That’s a weird looking Crenicichla scotti” and almost threw the fish back in the water. The color was a brownish-gold, not a steel grey like it should be for C. scotti. And the spots were all wrong. I decided to keep the odd-looker for photography, once we got back to Felipe’s house. On the way back, it hit me – it wasn’t a C. scotti at all! It looked like C. gaucho that Lucena and Kullander described in 1992. The black spots along the length of the body are in straight lines in C. scotti, while they are irregular in C. gaucho. This, again, was a previously unphotographed fish. Joy! Fast forward to August 2001. Felipe, who visits Sweden regularly, showed the fish to Sven Kullander, who said that the specimen did not match C. gaucho or C. scotti. (Upon his return from Sweden, Felipe emailed me in excitement: Sven vio los Crenicichla, el minuano y missioneira son correctos...pero el gaucho NO es gaucho, Sven NUNCA vio ese Crenicichla y esa especie es totalmente nueva!!!!) So we had an undescribed member of the C. scotti-group! Felipe had caught another “strange” pike in the state of Artigas, the state immediately to the north of Salto, similar to this one but with a spot on the dorsal fin – Kullander and Lucena mention that females of C. gaucho have a dorsal fin spot. I don’t know if females of this new species have dorsal fin spots – it could, as this characteristic is common in southern Atlantic coast pikes. Or the true C. gaucho could be distributed in the state of Artigas.

Back at Felipe’s home by the beach, just outside of Montevideo, we acclimated our catch. It looked like we had 5 male C. missioneira and one female. On closer inspection, I was blown away again – the ‘female’ was not a C. missioneira! The jaw structure on the ‘female’ was very different and its base coloration was greener. C. missioneira have prognathous lower jaws, meaning the larger lower jaw juts out past their upper jaws, giving them a bulldog-like appearance that is common to many predatory fishes. It is likely that this jaw structure helps gape-and-suck predators capture their prey. The odd ‘female’ had isognathous jaws, meaning the upper and lower jaws are of equal length, a characteristic seen in many detritivorous cichlids. No cichlid keeper should travel to Uruguay without the Lucena and Kullander paper – so I quickly referred to it and confirmed my suspicion. The fish belonged to C. minuano, another Rio Uruguay endemic previously thought to inhabit upper and middle Rio Uruguay only. It is a fair assumption from its jaw structure that C. minuano, like two other Rio Uruguay endemics, the snail-eating C. jurubi and the thick-lipped C. tendybaguassu, which uses its lips as gaskets while sucking insects from crevices, is not a specialized piscivore.

We observed all three species in Felipe’s tanks over the next week while we explored different parts of the country. C. missioneira and C. sp. aff. gaucho are typical pikes – rowdy, territorial and aggressive, but C. minuano seemed more mild mannered. Since C. minuano and C. sp. aff. gaucho had never been caught in Uruguay before, we left the two lone specimens for the fisheries and ichthylological authorities for diplomatic reasons. I knew what that meant: we’d be back! During our stay there, we did not catch C. celidochilus, known from only a few streams in northern Uruguay. I’m also certain that there are more undescribed cichlids in the state of Artigas. Road trip!

I did, however, manage to bring back to the United States, C. missioneira, C. punctata, C. vittata, Gym. Gymnogenys, Gym. Labiatus, Gym sp. Salto, Gym meridionalis, Gym rhabdotus, Gym balzanii, Cichlasoma pusillum, Cichlasoma facetum, C. sp. aff. facetum, C. sp. aff. oblongum and an undescribed Cichlasoma sp Salto II, a species that reminds me of the Central American Archocentrus species.

In the aquarium C. missioneira are hardy, territorial and uncomfortable in the upper levels of the aquarium. Their dorsally positioned eyes are reminiscent of rheophilic Crenicichla of the reticulata group like C. jegui and C. cametana. The positioning of the eyes may also explain their preference for occupying deeper waters. They are more aggressive than any other Crenicichla from Uruguay as I’ve had to separate them from each other after they reached just 4 inches TL, which is when it becomes easy to distinguish between the sexes – males have irregular spots on the caudal peduncle and fin. This species does not have a humeral spot or a prominent suborbital stripe and the females do not sport a dorsal fin spot, but both sexes possess rows of inclined vertical bars on the upper half of the body.

From a commercial perspective, this species is a dud – it gets big (8 inches from what I’ve seen) and is colorless – but I expect some curiosity from advanced hobbyists who seek fascinating behavior and not just color from their aquatic charges. These fish do a lot of chasing around the aquarium and are among the fastest and most powerful swimmers in the cichlid family. Their chasing behavior is almost too fast for the human eye to discern! Even more interesting is their food-searching behavior, while fairly adept at capturing and consuming live fish, these fish often dig into the substrate like eartheaters! They pick up substrate and spit it out nearby and inspect for edible things where they have just dug. This is previously unrecorded behavior in Crenicichla.

I have not seen any courtship behavior other than brief moments of tolerance between the sexes in each other’s territories and I hope these conciliatory moments are not just a result of sheer exhaustion from chasing. If you’re waiting for F1s from me, you may be in for a long wait, given their intense dislike for each other.

There are still at least three more pikes as yet unexported from Uruguay – stay tuned. I find it interesting that about half of the cichlid species of the country consists of Crenicichla, so it’s no doubt that I’ll be back in Uruguay when time, finances and responsibilities permit. Please don’t tell anyone that I went half way to the South Pole to catch a brown, mean fish. When normal people ask, I say “They have great beaches!” And they do.

I’d like to thank Felipe ‘Pipo’ Cantera and Marcelo Casacuberta for their help, friendship and hospitality during our visit, Jim Herman and Nathan Okawa for their companionship during the trip.

Site Data

- Collecting location of C. missioneira and C. minuano: Salto Grande, near Constitucion, Salto, Uruguay.

- GPS location: S 31° 04.042’ W 057° 50.731’

- Elevation: 260 feet

- Water temperature near shore: 92°F

- Water temperature in deeper areas: 85°F

- Air temperature: 89 – 96°F

- Humidity: 64%

- Water hardness: 31 ppm

- pH: 6.7 – 7.4

- Substrate: sand and small pebbles

- Water movement: none

- Other species caught here: C. lepidota, C. vittata, Gymnogeophagus balzanii, Gymnogeophagus sp. Salto, Cichlasoma pusillum, Leporinus sp., Serrasalmus sp., Hoplias cf. malabaricus., Loricaria sp., Corydoras sp. and numerous small Characins.

- Collecting location of C. sp. aff gaucho: stream by road from Constitucion to Espenillar, Salto, Uruguay.

- GPS location: S 30° 59.026’ W 057° 47.064’

- Elevation: 290 feet

- Water temperature: 77°F

- Air temperature: 81°F

- Humidity: 71%

- Water hardness: 168 ppm

- pH: 7.8

- Substrate: small stones to large rocks

- Water movement: moderate to rapid depending on width of stream

- Other species caught here: Ancistrus sp., Charax sp. aff. gibbosus, Pseudocorynopoma doriae, Leporinus sp. Red Lips., Crenicichla lepidota.

Arroyo Escuela, Cerro Largo, Uruguay. March 2001. References:

Lucena, C. A. S. and Kullander, S. O. 1992. The Crenicichla (Teleostei: Cichlidae) species of the Uruguai River drainage in Brazil. Ichthyol. Explor. Freshwaters, Vol. 3, No. 2, pp 97 – 160.

Casciotta, J. R. 1987. Crenicichla celidochilus n. sp. from Uruguay and a multivariate analysis of the lacustris group. Copeia, 1987: 883 - 891.

Carnevia, D., Rosso, A., Aycaguer, C., Pignataro, G., Varela, E., and Martegani, E. Aspectos Fisico-quimicos de las aguas interiores del Uruguay habitadas por Ciclidos. Instituto de Investigaciones Pesqueras. Boletin No 17. Pagina 43.

Home Pikes Neotropicals Collecting Photography Links Site map

http://geocities.datacellar.net/NapaValley/5491

http://geocities.datacellar.net/NapaValley/5491

Latest update: 13 August 2006

Comments on this page: email me at vin dot kutty at gmail dot com