![]()

The sleepy little town of Hannibal, Missouri was named for the adventurer who crossed the Alps in 218 B.C. It was on a warm day in the middle of June, 1895 that the Edwards family first heard the voice that was to reach heights higher than the Alps and to fall lower than the valleys.

The Edwards were a poor farming family who knew nothing of music. But their son, Clifford, found his interest in music stimulated during a visit to the big city of St. Louis. There, Cliff Edwards wandered into a store that was demonstrating the then-new Edison cylinder talking machine. The thought that the human voice could be "captured" on wax and heard over and over again completely fascintated little Clifford.

Cliff had been exposed to religious singing, but this "modern miracle" opened new doors to his inner drive for music and song. Much to the chagrin of the Edwards family, he could be heard singing this "new" music while performing his chores around the family farm.

It was inevitable that young Cliff Edwards would gravitate to the world of music. His first appearances in public were in the bars around Hannibal where his performing allowed him to partake of the free lunch table - an early device to bring in the drinking crowd.

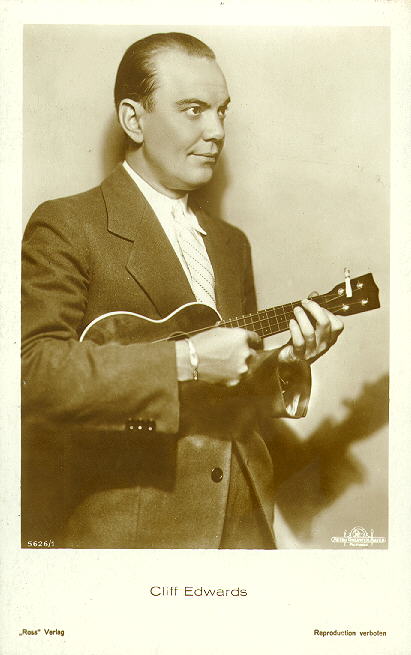

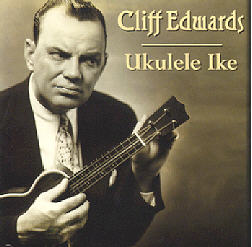

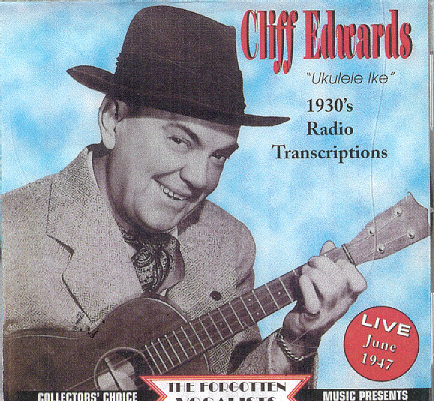

Eventually Cliff found his way back to St. Louis, where his musical career began in earnest. There he learned to play the ukulele, the instrument that was to be his trade mark for many years. He seldom had the benefit of musical accompaniment, so he had to improvise. This he did by cupping his hands over his mouth and imitating a trumpet (long before the Mills Brothers). About this time, Cliff experimented with what can best be described as "scat" singing.

By the mid twenties, success followed success for the lad from "down on the farm". He was signed for an appearance in George Gershwin's Broadway show "Lady Be good"; strummed his way through an exciting version of "Fascinating Rhythm". That was followed by the Ziegfeld Broadway musical, "Sunny", and again Cliff and his ukulele were show stoppers. He also appeared in several of George White's "Scandals." By now he had earned the title of "Ukulele Ike", a name which stuck through his entire career. It was a Chicago waiter with a bad memory who was partially responsible for Edwards' nickname. The hashslinger called him Ike, and Edwards later began billing himself as Ukulele Ike in a singing uke act at Mike Frizl's Arizona Cafe.

After finally landing a recording contract, Ukulele Ike began scoring one hit after another during the 20s and early 30s. "June Night" sold 3.2 million records, and "Sleepy Time Gal" over one million. "Toot, Toot, Tootsie" was associated with Al Jolson, but it was Ukulele Ike who introduced it and made it a hit. Rudy Vallee liked his style so well that he made him virtually a regular on his radio shows, and sandwiching these appearances were stints on many other radio variety programs. In all, Ukulele Ike was credited with selling over a total of 74,000,000 records.

Edwards was best known in Hollywood for introducing the song, "Singin' in the Rain" in The Hollywood Review of 1929 at Metro, where he was under term contract. Production Chief Irving Thalberg had seen him in an act in 1928 and signed him for a musical short, which won Edwards a four-year pact and a part for his feature film debut in Robert Montgomery's "So This is College"?

From the mid 20s to the mid 40s, Cliff was to appear in over 100 films, with even a cameo appearance in "Gone With The Wind". But it was in 1940 that he was to play the role that would be his most lasting. In 1940, the great Walt Disney was involved in producing his famous film, "Pinocchio". He was searching for the proper voice for Jiminy Cricket when he fortuitously bethought Cliff's voice - the voice with a smile - and he had his staff locate Cliff. It turned out to be perfect casting. Cliff Edwards, to this day, is best remembered for his work in that film. He appeared in 47 films in the 30s and 40s, but then his luck ran out.

For the next twenty years he had no glamorous jobs, two divorces and only occasional appearances on radio and in second-rate nightclubs. Cliff had two very bad habits: gambling and drinking. By the mid 60s, the former star was bankrupt.

For 30 years this unique entertainer's timeless singing and ukulele playing made millions for the "farm boy who made good", but when Cliff passed away in 1971 in a California nursing home, he died in abject poverty. His papers showed no next of kin and his body lay unclaimed for over a week. A newspaper woman who was visiting in the nursing home stumbled on the story and sparked a fund-raising campaign for a proper funeral for the once-famous "Ukulele Ike".

Sources for this article come from Roy Norman's liner note in "Cliff Edwards: Singing In The Rain" CD and several newpaper sources.