Last Updated: 15 May 2007

SHIMER FAMILY HISTORY AND GENEALOGY

PAGE

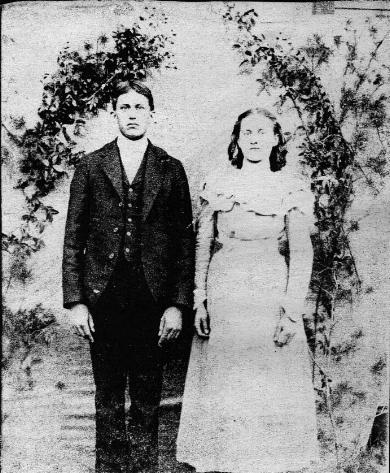

James G. Shimer and Elzena Haught Shimer, on their wedding day abt.

1900, Calhoun County, West Virginia

Check out more Shimer

Family Photos

(If you would like to submit a photo, contact me by email)

This page is designed to consolidate information I have received so that

members of this family can access and submit information for the good of

all

the family. I begun research into our family history back in 1990.

Since then, I have compiled a substantial amount of information from several

sources, to include: the History and Genealogy of the Shimer Family

in America by Allen R. Shimer, first published in 1908 (see link below).

SHIMER FAMILY

NEWSLETTER!!! ![]()

"A MARTYR" [A story

of the life and death of Leonard Schiemer]

MEMORIAL TO CHARLES WILLARD SHIMER

![]() "HISTORY

AND GENEALOGY OF THE SHIMER FAMILY IN AMERICA" VOL. I, by ALLEN R.

SHIMER, first published in 1908.

"HISTORY

AND GENEALOGY OF THE SHIMER FAMILY IN AMERICA" VOL. I, by ALLEN R.

SHIMER, first published in 1908.

(this is a link to the Adobe file on the BYU Library page)

Current Issue

Archives

The Shimer Family Crest

What I intend to provide you with the following history is a setting for the early Shimers, particularly those that accompanied the "Three Brothers" from the Palatinate of Germany to Philadelphia in 1749. Often times too much emphasis is given to the facts of genealogy: Surname, birth date, marriage date, death date. What is lacking is the circumstance, the day-to-day details of life. Although the passage time prevents us from knowing everything about the every day details of our ancestor's lives, we can imagine what was on their minds from the history of events that surrounded them.

With that, I hope you can enjoy this history and gain some insight into the lives of these early Shimers.

Chronology of German Immigration

Leaving Germany and Crossing the Atlantic

The German Society of Maryland

Friedrich Scheimer, son of Friedrich Scheimer

Michel Scheimer, son of Friedrich Scheimer

Daniel Scheimer, son of Friedrich Scheimer

James Shimer, son of Daniel Scheimer

The first known Shimer in America was a Jacob Scheimer, who arrived some time between 1700 and 1710. He was a Lutheran and settled in the area of Germantown, Pennsylvania. It is documented in Allen R. Shimer's book that Jacob Scheimer was said to have came from "Gersheim, Rheinpfalz, Bayern, Germany." The Rheinland Pfalz, which today is a separate state in Germany, was once a part of Bayern (Bavaria) and was also called the "Electorate" during the 17th Century. The region is also referred to as the "Palatinate" in English.

Much of what motivated Jacob Scheimer to emigrate to America continued to motivate later Scheimer immigrants in the following 40 to 50 years. Linda Zeoli, in an online article providing an overview of German Immigration in Maryland, gives a timetable for this period of 18th and early 19th century German Immigration:

Chronology of German Immigration

1680-1830

![]()

| 1682 | William Penn traveled throughout Germany, extending an invitation to all members of persecuted sects, who wished to leave their homeland, welcoming them to his colony of Philadelphia, where they could worship as they pleased. |

| 1683 | Francis Daniel Pastorius, of Frankfort, and his Mennonite followers, arrived in Philadelphia and founded Germantown, Pennsylvania. A member of the group, William Rittenhouse, built a paper mill in Germantown, the first of its kind in America. |

| 1709-1710 | Germans from the Palatine region in central Germany,

fled to England where the British shipped them to the New York Colony to

build ships for the Royal Navy, and guard the frontier against the

French.

By 1710 more than 3,000 Palatines had settled in the Hudson Valley (NY). Another group of about 650 Palatines, settled at New Bern, North Carolina. |

| 1719 | Between 6,000 and 7,000 Germans (many more from the Palatine) arrived in Philadelphia and spread out into the Pennsylvania farm country. |

| 1720 | An average of 2,000 Germans disembarked annually at ports along the Delaware River. Many were forced by poverty to come ashore as Redemptioners. |

| 1727 | Primary entry port for German immigrants was Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. By 1727 the German population of Pennsylvania had reached 20,000. |

| 1728 | Germans began to move into the western counties of Maryland -- Frederick, Washington and Carroll Counties -- via Pennsylvania. |

| 1729 | Town of Baltimore, Maryland founded. |

| 1734-1744 | 12,000 Swiss-Germans emigrated to America during this 10 year period. Many established communities in the southern colonies of South Carolina and Georgia. |

| 1745 | German population of Pennsylvania reached 45,000.

Frederick, Maryland was founded by German colonists, and later Hagerstown, Maryland founded by Jonathan Hager. |

| 1749 | "Peak" year for German immigration, over 6,000 immigrants found homes in the American colonies. (This is the year that the "Three Brothers" emigrated) |

| 1750 | Germans had established a string of back country settlements from the Mohawk Valley in New York, south to Savannah, Georgia. |

| 1755 | Zion

Church established in Baltimore, Maryland.

Germans of Maryland and Pennsylvania contributed toward the conclusion of the French and Indian War by providing horses and wagons to carry General James Braddock's expedition inland. |

| 1776 | At the time of the American Revolution there were

110,000 Germans in Pennsylvania, 25,000 in New York, 25,000 in Virginia,

20,000 in Maryland/Delaware, 15,000 in South Carolina, 15,000 in

New Jersey, 8,000 in North Carolina, 5,000 in Georgia.

Congress lured Hessian soldiers from British allegiance by promising them rights of citizenship and 50 acres of land to fight in the Continental Army. Over 12,000 Hession soldiers remained in America after the War of Independence. |

| 1778 | General Frederick Wilhelm Steuben appointed Inspector General of Revolutionary Army by Washington. Fought in a number of engagements during the war and remained in the U.S. at its conclusion. |

| 1781 | Stueben planted the regimental standard when Cornwallis surrendered at Yorktown. |

| 1783 | German Society of Maryland was founded to aid German and Swiss immigrants. |

| 1807 | German immigration spread west into central United States -- Great Lakes region and the prairie states. |

| 1828 | Discriminatory laws passed in the German states of Bavaria and Wurtemberg against Jews of German origin led to an exodus of German Jews to America. |

A great deal of information on the Jacob Scheimer family and descendants can be found on Eva Duke's home page. She has been working on the history and genealogy of the Jacob Scheimer Family, which came to America about 1710 from the Gersheim area of the Palatinate (present day Saarland) and settled in Eastern Pennsylvania and Western New Jersey. This is an awesome amount of research and has a lot of "The History and Genealogy of the Shimer Family in America" copied within it's pages. Thank you so much Eva for all your hard work!

Here is another link given to me by Robert Shimer to uploaded genealogy from the Jacob Scheimer (1679-1759) family. This page was created by Deborah and James Jackson.

The following is a copy of an article regarding the history of the Palatinate, from the Olive Tree Genealogy website:

PALATINE HISTORY

by Lorine McGinnis Schulze[This article has been published, with my permission as

Irish Palatine Story on the Internet

in Irish Palatine Association Journal, No. 7 December 1996]

The Palatinate or German PFALZ, was, in German history, the land of the Count Palatine, a title held by a leading secular prince of the Holy Roman Empire. Geographically, the Palatinate was divided between two small territorial clusters: the Rhenish, or Lower Palatinate, and the Upper Palatinate. The Rhenish Palatinate included lands on both sides of the Middle Rhine River between its Main and Neckar tributaries. Its capital until the 18th century was Heidelberg. The Upper Palatinate was located in northern Bavaria, on both sides of the Naab River as it flows south toward the Danube and extended eastward to the Bohemian Forest. The boundaries of the Palatinate varied with the political and dynastic fortunes of the Counts Palatine.

The Palatinate has a border beginning in the north, on the Moselle River about 35 miles southwest of Coblenz to Bingen and east to Mainz, down the Rhine River to Oppenheim, Guntersblum and Worms, then continuing eastward above the Nieckar River about 25 miles east of Heidelberg then looping back westerly below Heidelberg to Speyer, south down the Rhine River to Alsace, then north-westerly back up to its beginning on the Moselle River.

The first Count Palatine of the Rhine was Hermann I, who received the office in 945. Although not originally hereditary, the title was held mainly by his descendants until his line expired in 1155, and the Bavarian Wittelsbachs took over in 1180. In 1356, the Golden Bull ( a papal bull: an official document, usually commands from the Pope and sealed with the official Papal seal called a Bulla) made the Count Palatine an Elector of the Holy Roman Empire. During the Reformation, the Palatinate accepted Protestantism and became the foremost Calvinist region in Germany.

After Martin Luther published his 95 Theses on the door of the castle church at Wittenberg on 31 October 1517, many of his followers came under considerable religious persecution for their beliefs. Perhaps for reasons of mutual comfort and support, they gathered in what is known as the Palatine. These folk came from many places, Germany, Holland, Switzerland and beyond, but all shared a common view on religion.

The protestant Elector Palatine Frederick V (1596-1632), called the "Winter King" of Bohemia, played a unique role in the struggle between Roman Catholic and Protestant Europe. His election in 1619 as King of Bohemia precipitated the Thirty Years War that lasted from 1619 until 1648. Frederick was driven from Bohemia and in 1623, deposed as Elector Palatine.

During the Thirty Years War, the Palatine country and other parts of Germany suffered from the horrors of fire and sword as well as from pillage and plunder by the French armies. This war was based upon both politics and religious hatreds, as the Roman Catholic armies sought to crush the religious freedom of a politically-divided Protestantism.

Many unpaid armies and bands of mercenaries, both of friends and foe, devoured the substance of the people and by 1633, even the catholic French supported the Elector Palatine for a time for political reasons.

During the War of the Grand Alliance (1689-97), the troops of the French monarch Louis XIV ravaged the Rhenish Palatinate, causing many Germans to emigrate. Many of the early German settlers of America (e.g. the Pennsylvania Dutch) were refugees from the Palatinate. During the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars, the Palatinate's lands on the west bank of the Rhine were incorporated into France, while its eastern lands were divided largely between neighbouring Baden and Hesse.

Nearly the entire 17th century in central Europe was a period of turmoil as Louis XIV of France sought to increase his empire. The War of the Palatinate (as it was called in Germany), aka The War of The League of Augsburg, began in 1688 when Louis claimed the Palatinate. Every large city on the Rhine above Cologne was sacked. The War ended in 1697 with the Treaty of Ryswick. The Palatinate was badly battered but still outside French control. In 1702, the War of the Spanish Succession began in Europe and lasted until 1713, causing a great deal of instability for the Palatines. The Palatinate lay on the western edge of the Holy Roman Empire not far from France's eastern boundary. Louis wanted to push his eastern border to the Rhine, the heart of the Palatinate.

While the land of the Palatinate was good for its inhabitants, many of whom were farmers, vineyard operators etc., its location was unfortunately subject to invasion by the armies of Britain, France, and Germany. Mother Nature also played a role in what happened, for the winter of 1708 was particularly severe and many of the vineyards perished. So, as well as the devastating effects of war, the Palatines were subjected to the winter of 1708-09, the harshest in 100 years.

The scene was set for a mass migration. At the invitation of Queen Anne in the spring of 1709, about 7 000 harassed Palatines sailed down the Rhine to Rotterdam. From there, about 3000 were dispatched to America, either directly or via England, under the auspices of William Penn. The remaining 4 000 were sent via England to Ireland to strengthen the protestant interest.

Although the Palatines were scattered as agricultural settlers over much of Ireland, major accumulations were found in Counties Limerick and Tipperary. As the years progressed and dissatisfactions increased, many of these folk seized opportunities to join their compatriots in Pennsylvania, or to go to newly-opened settlements in Canada.

There were many reasons for the desire of the Palatines to emigrate to the New World: oppressive taxation, religious bickering, hunger for more and better land, the advertising of the English colonies in America and the favourable attitude of the British government toward settlement in the North American colonies. Many of the Palatines believed they were going to Pennsylvania, Carolina or one of the tropical islands.

The passage down the Rhine took from 4 to 6 weeks. Tolls and fees were demanded by authorities of the territories through which they passed. Early in June, the number of Palatines entering Rotterdam reached 1 000 per week. Later that year, the British government issued a Royal proclamation in German that all arriving after October 1709 would be sent back to Germany. The British could not effectively handle the number of Palatines in London and there may have been as many as 32 000 by November 1709. They wintered over in England since there were no adequate arrangements for the transfer of the Palatines to the English colonies.

In 1710, three large groups of Palatines sailed from London. The first went to Ireland, the second to Carolina and the third to New York with the new Governor, Robert Hunter. There were 3 000 Palatines on 10 ships that sailed for NY and approximately 470 died on the voyage or shortly after their arrival.

In NY, the Palatines were expected to work for the British authorities, producing naval stores [tar and pitch] for the navy in return for their passage to NY. They were also expected to act as a buffer between the French and Natives on the northern frontier and the English colonies to the south and east.

After the defeat of Napoleon (1814-15), the Congress of Vienna gave the east-bank lands of the Rhine valley to Bavaria. These lands, together with some surrounding territories, again took the name of Palatinate in 1838.

[Permission to reprint is granted provided the following terms are followed: This article may be reproduced as long as it is not changed in any way, all identifying URLs and copyright information remain intact (including this permission), and a link is provided back to Olive Tree Genealogy]

The following history was taken from the book Pfalzer

in Amerika / Palatines in America by Herr Roland Paul and

Herr Karl Scherer. Herr Paul is the director of the Institut

Fur Pfalzische Geschichte und Volkskunde (Institute for Palatine

History and Folklife Studies) located in Kaiserslaughtern, Germany. The telephone

# is: 011-49-631-3647. They have a great list of emigrants from the Pfalz

to America on micro-fische.

A lot can be gained by an understanding of the history of the region during the period of immigration (17th and 18th Centuries). The Electorate was devastated after the Thirty Year's War, from 1618 to 1648. It is estimated that the region lost 70% of its population during this war. The ratio of cultivated soil to waste land before the war was 3:5. After, it fell to 1:9. The Elector Karl Ludwig attempted to attract the populous to return from exile after the war, with tax breaks and other incentives during the 1650's and 60's. This did not attract the numbers of refugees that Ludwig was after, so he advertised for any good citizen of any country to come to the Palatinate and they would be free of religious persecution. This attracted many Swiss Mennonites, French Huguenots, refugees from the Netherlands, Walloons, Waldenses and Tyroleans, as well as discharged mercenaries from the armies.

There were no less than five armed conflicts in the last 50 years of the 17th century in the Palatinate. This, along with a fear of religious persecution from the intolerant French Catholics to the west and a general economic depression, began the exodus. The promise of fertile land and religious tolerance in "Penn's Woods" attracted the Pfalzer in droves. The estimated emigration between 1670 and 1789 was nearly 100,000 Palatines.

According to Linda Zeoli, these Palatinates left Germany for several reasons:

Why Did They Leave Their Homeland?

![]() Devastation of War

Devastation of War

From the mid-16th century to the mid-17th century, Europe was involved in a series of bloody wars, caused by a mixture of religious, political, and economic differences. The worst of these bloody conflicts was the Thirty Years War which lasted from 1618 to 1648. The final settlement, for Germany, resulted in a "patchwork" of over 300 independent states, both large and small, whose ruler could choose the people's religion--Lutheran, Calvinist, or Catholic. In the wake of the wars, German lands had been devastated, and people's homes and livelihoods destroyed. Some parts of Germany lost as many as two-thirds of their people in the Thirty Years War, while survivors faced disease and starvation. Is it any wonder that such hard times brought the first migrations to America?

![]() Agricultural Failures

Agricultural Failures

Another factor that caused Germans to emigrate was an extremely harsh winter in the early 18th century. The winter of 1708-1709 was the most bitter on record. Fruit trees and vines were killed by deep frost and heavy snow. No doubt the following report was exaggerated "in January wine froze into solid blocks of ice and birds fell dead in mid-flight." (Frank/Brownstone 1989). Periodic crop failures, including potato famines, sent waves of Germans across the Atlantic for the next two centuries.

![]() Religious Persecution

Religious Persecution

The result of decades of religious warfare in Germany led many Germans to migrate to America and the promise of religious tolerance. Various religious groups suffered persecution in many German states over the centuries. Lutherans and Reformed Church members came to America from Bavaria and Wurzberg. Catholics arrived when they were expelled in 1732 by the Protestant Count Leopold of Firmian. From the 1830s to the 1880s, anti-Semitic laws passed in some German states sent many Jews to America. In all, Germans were the largest immigrant group to include sizeable numbers of all three major Western religions [Catholic, Protestant and Jew].

![]() Land Scarcity

Land Scarcity

Another reason for leaving Germany was overpopulation and scarcity of land. Many farmers, especially in the southwest, had outgrown their land. It had been divided and subdivided in families until it was no longer large enough nor profitable enough to support a family. The promise of cheap and fertile land in America was too tempting an opportunity to overlook.

![]() Political Oppression

Political Oppression

Political differences were the leading cause of emigration in the mid-19th century. Intellectuals and reformers dreamed of a united, democratic Germany. Scholars, students, and liberals of various backgrounds joined together to bring about unification. Most political power was in the hands of the rich and the aristocracy. In 1848 the liberals were successful, for a time, in Germany. A Parliament was elected, but due to disagreement and division on important issues the effort collapsed. Prussia took over the unification process. Thousands of reformers left Germany for America. They became known as the "Forty-Eighters."

This is the period in which the Shimer ancestors came to America. I have already mentioned Jacob Scheimer. According to Allen R. Shimer's "History," the next known Shimer immigrant was a John Conrad Shymer (the name in old records appears as Scheimer, Scheumer, Shymer, Sheymer, Shoimer, Sheimer, etc). He came to this country in 1732 with his daughter, Maria, and wife, Anna. Due to his having no male descendants, his branch of the Shimer family became extinct by the Shimer name. His daughter married a Mr. Shunk, the ancestor of Governor Shunk of Pennsylvania. The next known emigrant Shimers were the "three brothers," Friedrich, Daniel and Michel Scheimer. They came to America in 1749, sailing aboard the ship Edinburgh, starting from Rotterdam on September 15th, 1749. They settled in Northern Maryland, and Chester and Bedford Counties, Pennsylvania. I am a descendant of Daniel Scheimer. I have extensive information regarding the generations of descendants from him. I am currently trying to piece together the information as to the origins of the Shimer family in Germany.

[Check out the Palatines to America Homepage, a worthwhile organization online that conducts research into the history of Palatine Emigrants to America.]

The "Three Brothers", as they were called by Allen R. Shimer in his book, seem to have originated from the area of Gersheim, in the Palatinate, as well as did Jacob Scheimer. They were also accompanied by a Anton Scheimer and a Johannes Scheimer, although Allen Shimer does not mention them in his "History" (Anton's name shows up on the passenger manifest for the "Edinburgh" as well as the brothers). Esther Endecott, who is a Shimer descendant and a researcher who volunteers with the LDS genealogy libraries in her area, states that the Pennsylvania Archives, with regards to the Oath of Allegiance record that the three brothers had to take once arriving in Philadelphia, shows that they hailed from the region of Gersheim (which is in modern-day Saarland between Saarbrucken and Zweibrucken in the southwest of Germany, near the French border):

From

Rotterdam, Netherlands to Philadelphia, PA on Ship

Edinburgh

The

Foreigners whose names are underwritten, imported in the Ship Edinburgh, James

Russel, Master, from Rotterdam, but last from Portsmouth in England, did this

day take the Usual Oaths to the Government.

By list 163. 360 whole Freights, from the Palatinate of the Rhine Valley

near Gersheim Germany. Daniel

Scheimer, Friedrich Scheimer, Michel Scheymer, Anton Scheimer, Johannes Scheimer

were listed on this list. List 132

C at the Court House at Philadelphia, Friday the 15th 7th month 1749.

[Here is a link that shows the list of passengers for the Edinburgh at the following website, which also references List 132 C as the source: http://www.progenealogists.com/palproject/pa/1749edin.htm ]

At this point, the most conclusive evidence that the original Shimer family descending from Jacob Scheimer (The First, as stated by Allen R. Shimer, and those who primarily settled in the northeastern area of Pennsylvania in Lehigh and Northampton Counties, and western New Jersey) and the "three brothers" are related might be that they all hailed from the same small town in southwestern Germany, and departed for America within forty to fifty years of one another. Another recent discovery that I made on the LDS familysearch.org website is a name for the father of Daniel, Friedrich, and Michel Scheimer is a Friedrich Scheimer, born about 1701 in Gersheim. Friedrich may very well have been a cousin or nephew of Jacob Scheimer, who was nearly a generation older than he. This is the first time I have been able to make a direct connection to a name in Germany in nearly two decades of research into the "Three Brothers" Shimer family.

At any rate, quite a bit of information was written by Allen R. Shimer in his "History" regarding that older line of the Shimer family. I am going to concentrate on filling in some of the historical and genealogical data for the "Three Brothers" line on this page, although, when seen from the point of view that we are all branches of a greater trunk and are related through common Shimer ancestors, I welcome any information on any Shimer ancestor and descendent.

Leaving Germany and Crossing the Atlantic

There were many reasons for these Germans to decide to leave their homeland and seek better lives in the New World. According to an article on the ProGenealogists website, titled "18th Century German Emigration Research", By Gary T. Horlacher, 2000:

18th Century German Migration Map

This was an era of change in central and southern Germany. Many areas had been devastated during the 30 Years' War (1618-1648) and the subsequent War of Louis XIV (1688-1697). The areas hit hardest were those bordering France and along the Rhine River (Rheinland, Pfalz, Baden, Hessen, etc.). Many of these towns were partially or completely depopulated, so that new settlers were recruited to re-settle from France (Huguenots), Switzerland, and other parts of Germany.

As these villages slowly rebuilt and began to flourish again, the population quickly rose. Within about two generations there was already an overabundance of workers. Without hope of owning land or making a good living, the stories of possibilities in America began to sound enticing!

Although the most well known emigration was the settlements in south east Pennsylvania and Maryland, there were also large groups of Germans who came at this time to Nova Scotia (Neu Schotland), New England (Neu England: Boston, Waldoboro), New York, Virginia, Georgia, and South Carolina (Karolinas). The thumbnail image, below, shows where these centers of German emigration were in colonial North America.

German Settlement in North America

[For more German-specific genealogical research, visit the German Genealogical Digest]

A great description of the journey many of these Palatinates had to take from their abandoned homes to the port at Rotterdam is provided on Donald L. Spidell's website. Mr. Spidell details the trials and tribulations of his family's migration out of Germany, Switzerland, and France to the port of Rotterdam and on to the New World. The following is taken from his article titled, "The Great Palatine Migration":

The Palatinate to The Netherlands

The first part of the emigration route was down the Rhein river to the Netherlands. Few would have been able to make the trip without help. An underground railroad was established, and Protestant families along the Rhein gave sanctuary to the refugees as they made their way to the new world.

Origin of the Hans Michael Rohrer Family

The family of my immigrant ancestor, Hans Michael Rohrer originated from the Rhein valley in Switzerland. Hans Michael Rohrer was married and his children were born in Markirch, Elsass, Germany, which is now called Ste. Marie-aux-Mines, Haut-Rhin, France. Johannes Rohrer, his last born son while he was in Markirch, was born 1 Nov 1701. It was customary in that area and at that time to give children the names of saints, thus every male child would be named after the patron saint of the family. Sometimes every girl child will also be found with the same common first name, but not so often as the boys. Then every child would have a distinct middle name by which he would be known. Thus it was common for a German family to have all of its sons named some form of John with all but one of them having middle names. Some family traditions say that this way when the devil came for a child, he would become confused as to which John was which. Two sons of Hans Michael were named Hans Jakob and Hans Michael. The next two sons were given the name of Johannes Jakob and Johannes. Actually we now have five Johns, but I am going to focus on the two named, Johannes.

Flight From Markirch

The family of Hans Michael Rohrer, Sr. was forced about the year 1711 to move from Markirch to escape religious persecution. Johannes Jacob, the third son was captured by the French while he was trying to save some of the family possessions. He somehow escaped from prison, and he followed the usual route of the Palatine Emigrants. He escaped into Southern Germany. His final destination was Holland and the Dutch followers of Menno Simmons, the Mennonites. The Mennonites helped the Palatinates to emigrate to the American Colonies, usually via London. Actually the ship owners usually sold the emigrants to England for their passage fees.

Most of the Palatines were then put in one of two refugee camps: there was one outside of London, and when that one got too full, one was set up in Ireland. There is still a colony of Germanic people in Ireland to this day. From the refugee/concentration camps, the English would ship people to any one of a number of its colonies throughout the world. Family tradition states that Johannes Jacob studied veterinary surgery in London, and then migrated to the colonies and settled in Lancaster County, Pa. Another story states that he was sold into bond slavery, he ran off and then he married the daughter of a rich land owner, Maria Souder. Actually a family Bible states that John Jacob married Maria Souder in Mannheim in 1732 which is the same year that he arrived in Lancaster, Pa. with his bride and her father. Mannheim was a Protestant and French Huguenot refuge in Germany. We can assume in this case that the bride's father paid for their passage.

Flight From Strasburg

In the meantime, Johannes Rohrer, the fourth son, went with his family as they escaped the French and they settled in Strasburg. About the year 1725, religious persecution forced the family of Hans Michael, Sr. to once again flee its home. As they left Strassburg, Johannes was attempting to save some of the family possessions from their home, when he was separated from his family. He was captured by the French, and he was the second son that the family lost in this manner. He later escaped or was forced to emigrate. At this time he was about 24 years old. He too, probably followed the route of the Palatine Migration, and he was most likely the Johanne Roer who landed at Philadelphia in the ship "The Mortonhouse" on 24 August 1728.

It is speculated that he worked for four years on an English plantation near Philadelphia to pay off his passage fee. The next heard of him was in the year 1732 when Johannes went to Lancaster Co., Pa. and found his brother Johannes Jacob Rohrer. Johannes married Elizabeth Snavely about 1735 and settled near his brother in Lampeter twp. He bought a farm on the Conestoga Creek, 8 Oct 1763.

England

England saw the German refugees as being worth their weight in gold. However, England had to ensure that the European refugees would not cost too much for upkeep. They were also not to be allowed to become citizens. That was the reason for the refugee camps.

Refugee Camps

The camps were as refugee camps always are. They were tent cities that were too crowded, too dirty, and too unsanitary for comfort. Most of the history books (of the ones that even mention them) assure us that the English Queen graciously provided the essentials required for living in the camps, but I am sure that it was not a comfortable time for the Palatines.

The Trip

As soon as a boat became available, it was packed with refugees to capacity and beyond. The voyage to the colonies was miserable. The boats were over-crowded, there was no privacy, the drinking water was polluted, and the food was vermin-ridden. Only enough food and water was supplied to provide for the longest average trip. If a boat was delayed by the weather, the refugees, who were considered as cargo, were in trouble. Consider the description of a rather severe ocean voyage by the Ulster Scots, who shared many of the privations of the Palatines: Voyage. In spite of all the difficulties, many of the people made the trip in relative good health.

At least they did arrive at their destination in the new world. Well…..not always! Most of them arrived in Pennsylvania, which was their primary destination. Some were let off in New York, and some were let off in Virginia, but there were others who were dropped off in places like Australia, and even in Brazil. In the case of the German colony in Brazil, which is still in evidence in modern times, the ship was driven off course by storms, and the captain just dropped off his passengers, without even trying to recoup his losses by continuing on to the English colonies. Once the ship arrived at any port, the captain of the ship sold the refugees into bond slavery.

The Palatine Colonists

Once the Palatine emigrants got established in the colonies, they in turn, started helping out other emigrants. The Palatines of America monitored the schedules of ship arrivals, and many of them met the ships which were due to have Palatines on board. In this way many of the colonists were able to pay for the passage of family members and literally to buy them out of slavery.

Johannes Jakob Rohrer was one of the Palatine emigrants who met ships of docking Palatines at the harbor. One day, he lucked out, and one of the first passengers whom he met coming off one of the ships, turned out to be his father. Johnnes, who now called himself John, immediately recognized his parent, but the latter did not know his son. Johannes Jakob's mother had died and his father was married again, and had two or three sons by his second wife. They were destitute of means and expected to be sold for their passage money. John paid the demands, brought his father and his father's family with him, and aided his half brothers to property near what is now Hagerstown, Maryland. I am descended from Martin Rohrer, one of the sons, who was set up on land in what is now Washington County, Maryland. Thus the event in history known as the Great Palatine Migration came to an end for my family.

On a page from the Church of the Brethren Network, titled "The Migration and Expansion of the Brethren in America", Written by Ronald J. Gordon, published February 1996, the trans-Atlantic crossing is described in greater detail:

Harrowing were the experiences of people who risked their lives and property to cross the Atlantic Ocean from Europe to America during the Sixteenth to Eighteenth Centuries. The season for passage began in early May and ended in late October with each westerly voyage from England requiring at least seven to eight weeks with good tail winds, and often ten to twelve weeks if the winds were not favorable. A typical journey for refugees fleeing religious persecution in Europe or indentured servants contracting years of labor for the cost of passage would often begin in Rotterdam or Amsterdam and then proceed to England for supplies.

18th Century Sailing Ship |

Death was a steadfast companion of both passengers and crew for many would perish. Burial at sea can be an especially difficult and trying experience. One does not have the expected proper time for remorse because the body must be cast overboard in a short period of time. The sea does not allow family members to return to an exact spot in order to grieve as is true of a land based cemetery where people can repeatedly return, where flowers can serve as a visible closure, and the certainty that graves usually remain unmolested. Death at sea can be a cruel experience. You cannot return. There is the haunting reality that the body will probably be eaten. Family members reproach each other for persuading them to make the journey. Wives reproached their husbands for children that were lost. Husbands lamented most piteously for convincing their family to make the journey. Children bemoaned parents for their helplessness. Witness accounts record unbelievable despair and misery. As more and more people die, it becomes almost impossible to console the relatives.

"Many hundred people necessarily die and perish in such misery, and must be cast into the sea, which drives their relatives or those that persuaded them to undertake the journey, to such despair that it is almost impossible to pacify or console them. In a word the sighing and crying and lamenting on board the ship continues day and night, so as to cause the hearts of even the most hardened to bleed when they hear it."On the Misfortune of Indentured Servants, Gottlieb Mittelberger, 1754.

Another account of the misery of those crossing the Atlantic at the time our Scheimer ancestors did is provided by Mr. Spidell. Further details can be found on his website regarding the Scots/Irish Immigration of the 1700s:

These Scheimers who crossed over on the "Edinburgh" surely were no strangers to adversity. Although it is not known what their religion was precisely, Friedrich Scheimer is found later to be a contributor to the construction of a new Lutheran Church in Chester County, Pennsylvania. Some of the Shimer descendants today that still reside in Allegany County, Maryland are members of the Brethren Church. The Brethren take their roots from the earlier Anabaptists, formed immediately after the start of the Protestant Revolution in the early 16th century. Leonard Schiemer was martyred an Anabaptist preacher in 1528 (see article below).

The trip aboard the "Edinburgh" must have been long and arduous. Arriving at the Port of Philadelphia, the Scheimers would have been welcomed into a foreign environment by all regards. It is unknown whether any of them spoke English at all upon their arrival, but once passed through the immigration process, including the obligatory Oath of Allegiance to the Crown of England, they would have been able to soon find their familiar German culture and citizens all around. The Germans were migrating away from the city, and along Indian paths into the western interior of Pennsylvania, Maryland, and into Virginia.

B ut before these Scheimers could establish a life of their own in the New World, it is quite possible that they had a debt to repay.

Another hardship that many of these Palatinates had to endure was the practice of Redemption forced upon them in order to pay for their voyage across the Atlantic.

Donald Spidell elaborates on this stage of the early Palatine emigration process in his article on The Great Palatine Migration:

The Bond

The Contract

In many cases, the officials at each point along the way held up the emigrants for various fees and charges. Some of the most onerous of the officials they encountered were the ship captains. Before boarding the ship, the Germans were made to sign a contract. Since the whole migration program was essentially an English project, and the destination was an English colony, the contract was in English. Many of our ancestors couldn't have read it even if it were in German. They were just told by mouth that they would be required to a time of service in the colonies at their destination. As it turned out, the contract was for a certain amount of money to be paid at their disembarkation. Even if a man or woman died on board the ship, the spouse was obligated to pay for the passage fees of the deceased. If both parents died, the children were held to the obligation to pay for their parents. The trip usually lasted from 3 to 6 weeks. Many got sick on the way, and in the book, "Erster Teil der Geschichte der Deutschen Gesellschaft von Pennsylvanian" by Oswald Seidensticker, estimates that, in one year, over 2000 died on the way.

Disembarkation

When the ship reached a harbor, the ones who could pay the disembarkation fees, were allowed to leave the ship immediately. Those who could not pay and who were healthy were kept on the ship until a person who would buy the bond for the full amount of money owed came onto the ship, examined the "redemptioners" chose one or more, and paid the fees. At this point many families were separated when family members were bought by different "masters". This process may take days or weeks, while the sick ones were still on the ship, with the poor conditions and little or no medical care. Once all of the healthy ones were sold at full price, then the sick ones were auctioned off for whatever price they could bring. The trials were also not over for those who could pay their own fees. Many ports, especially in New York, charged their own disembarkation fees.

Bond Slavery

As for the "redemptioneers" the usual amount of time that a Palatine spent in bond was four years, but even that at times was variable. Many of the children, especially those who were orphaned, or who were separated from their parents and lost contact with the rest of the family, had to serve until they were 21. Some of the bond holders kept the Palatines, and the Irish, who were treated in much the same way, for as long as it took for the immigrants to pay off their debts. Also some of the bond holders were very creative in the way they computed the debts of their bonded, and charged for such things as room and board.

A further study of this practice is stated below by Linda Zeoli:

Redemption: The practice of shipping immigrants across the Atlantic without payment of fare. In return they had to sign a contract to agree to repay or redeem the "loan" of passage money within a specified period of time after arrival in America. If they could not pay off the contract in that (usually short) time, and most could not, the captain of the ship would sell them to the highest bidder. The immigrants would then be forced to work for the new contract holder for a number of years, as specified in their contract.

This practice was similar to indenture; however, the terms of indenture began at the point of embarkation. In other words, passage was paid by the contract holder (in America) before the indentured immigrant boarded a ship and the time of servitude was specified in the contract before they left Europe.

Redemptioners were not slaves, since their contract specified a limited term of service. But in practice, they had little more freedom than did slaves. Oftentimes families were separated by this practice upon arrival in America.

Gottlieb Mittleberger came to America in 1750 and returned to Germany four years later with the following report about the miseries suffered by the redemptioners:

When the ships have landed after their long voyage, no one is permitted to leave them except those who pay for their passage or can give good security; the others, who cannot pay, must remain on board the ships till they are purchased, and are released from the ships by their purchasers . . .

The sale of human beings in the market on board the ship is carried on thus: Every day Englishmen, Dutchmen and High-German people come from the city and other places, in part from a great distance, and go on board the newly arrived ship that has brought and offers for sale passengers from Europe, and select among the healthy persons such as they deem suitable for their business, and bargain with them how long they will serve for their passage money, which most of them are still in debt for. When they have come to an agreement, it happens that adult persons bind themselves in writing to serve three, four, five, or six years for the amount due by them, according to their age and strength. But very young people, from 10 to 15 years, must serve till they are 21 years old. (Furer 1973, 91)

![]()

Assistance for the plight of Redemptioners came from the General Assembly of the State of Maryland, which passed laws in 1818 as follows:

An Act Relative to German and Swiss Redemptioners

"Whereas it has been found that German and Swiss emigrants, who for the discharge of the debt contracted for their passage to this country are often obliged to subject themselves to cruel and oppressive imposition by the masters of the vessels in which they arrive, and likewise by those to whom they become servants, be it enacted . . . "

Various sections of this Act provided the following: a translator as register of contracts, regulation and recording of contracts, that no minor be indentured "except by parents, next of kin or orphans court," master has to provide minors under the age of 21 with at least two months schooling per year, no contract for service longer than 4 years, immigrants not to be detained aboard ship for more than 30 days, removal to shore of any sick or ill-treated immigrants, no children to be answerable for passage for parents (dead or alive), and no surviving spouse for decedent one. (Cunz 1948, 433-434)

It is unknown whether any of the Scheimers who crossed the Atlantic in 1749 aboard the "Edinburgh" where forced to repay their disembarkation fee through redemption. However, unless they were able to come up with the money beforehand, it is most likely that they did have to work off their debt through redemption. This may well explain why they went in different directions after arriving in the colonies.

The German Society of Maryland

One consequence of the misery these German immigrants endured was the creation of societal organizations to attempt to mitigate the suffering of these immigrants and to provide them with some representation upon arrival in the colonies. One of these organizations was the German Society of Maryland. Founded in 1783, this society's purpose is spelled out in a statement published shortly after its founding. An account of the hardships of the redemption system is found in an article on the the society's web page, titled "Pioneers in Service The German Society of Maryland 1783 - 1981," by Klaus G. Wust, it states:

Considering

the many hardships...

"In 1783 a very benevolent German Society was established at Baltimore in

Maryland for the succor to poor strangers, sick people, in short all those in

need among the Germans arriving there (not unlike the German House in Jerusalem

which was founded six centuries ago by the merchants of two Hanseatic cities,

Luebeck and Bremen, at first only for the care and support of the sick and

wounded but later nevertheless growing into a knight's order capable of

conquering kingdoms)." With this statement begins the earliest

account of The German Society of Maryland. For more than four decades

Germans from the Old Country and from neighboring Pennsylvania in increasing

numbers had come to the new town at the mouth of the Patapsco which was readily

developing into an important port. They had braved all adversities of

pioneer life. They had founded their own churches where they worshipped

and prayed in the language of their fathers. When the Revolutionary War

broke out, they had placed their abilities and their skills as well as their

lives at the disposal of the new homeland where most of their children had been

born. By virtue of their thrift and hard work many among the Germans in

Maryland had achieved a moderate prosperity and their daily lives began to

become adjusted to the growing city of which they were a part.

It is to the credit of these early German inhabitants of Baltimore and other

Maryland communities that they did not content themselves with having achieved a

secure and prosperous home for themselves and their families, but envisaged a

broad program of aiding those who would follow them into the new country after

the war and of protecting them from exploitation and abuse. They still

remembered the vicissitudes of immigrant life. Those who were fortunate

enough to have at their disposal sufficient means to pay for their ocean passage

and to buy a homestead and maybe even to keep a little reserve for the first

lean months in the unknown land, knew only the struggle of readjustment among

strangers. But even for them the memory of the first years spelled

hardship and insecurity. Some of the Germans, however, like many of their

fellow immigrants from the British Isles, had come to America completely

penniless. The owners and captains of vessels were willing to take such

persons across the Atlantic, if the emigrants (or in the case of minors, the

parents or guardians for them) would sign a contract stipulating that upon their

arrival they would pay for the passage by letting the captain hire them out as

servants for a term of years to masters willing to advance the amount of the

passage money. Emigrants who entered into such a contract were called

"redemptioners" because by binding themselves for service for a

certain number of years they "redeemed" themselves of their debt for

the passage. They also became known as "indentured servants," a

term stemming from the fact that the contract forms were indentures.

For several years the redemptioners had come mainly from the British Isles.

The growing abuses of this system having become known in Britain,

rigorous

laws and measures were adopted and enforced for their better protection.

Letters and articles abounded in English newspapers warning poor people from

entering into such contracts. Public opinion was successfully aroused

against the "emigrant runners." Now the latter turned toward the

continent in search of a continuation of their lucrative trade. In the

decades before the Revolutionary War they induced many Germans and Swiss

desiring to go to America to bind themselves for the passage. Little did

the emigrants know or suspect what was in store for them after they went aboard.

The contracts which the redemptioners had to sign in the Dutch or Northern

German ports, and which few of them fully understood, contained the proviso,

that if any passenger died during the voyage, the surviving members of the

family, or the other redemptioner passengers would make good his loss.

Thus, a wife who had lost her husband at sea, or her children, on her arrival

would be sold for five years for her own passage and for an additional five

years for the fare of each of her dead relatives, although they may have died in

the very beginning of the voyage. If there was no member of the family

surviving, it was common practice to add the time of the deceased to the term of

service of the surviving fellow passengers. The captain usually

confiscated and kept for himself the effects of the dead. This meant that

the shipping merchant and the captain would gain by the death of a part of their

cargo. Records of the emigrant trade in the 18th century seem to

substantiate the assumption that many a captain kept this additional source of

profit well in mind.

Once in an American port, the redemptioners were not allowed to choose their

masters nor the kind of service most suitable to them. Some were fortunate

in being acquired by humane masters or finding interested parties who would use

them in the trade they had learned at home. But frequently the penniless

newcomers were brutally taken advantage of. They were often separated from

their families, the wife from the husband, and children from their parents, and

were disposed of for the term of years, often at public sale to masters living

far apart, and always to the greatest advantage of the shipper.

Contemporary sources cite many examples of inhuman treatment, how they were

literally worked to death, receiving insufficient food, castaway clothing and

pitiful lodging. Cruel punishments were inflicted on them for the

slightest offense by merciless and brutal masters. While a certain number

of German redemptioners arrived at Annapolis and Baltimore prior to the

Revolution, this practice had not reached alarming proportions in Maryland

ports. Most of the German redemptioners were landed at Philadelphia where such a

large number of brutal offenses became known that prominent German citizens

banded together in 1764 to found the first German Society in North America for

the protection of the newcomers. Already during the first year of its

existence, the Society procured laws for the protection and aid of German

immigrants from the Pennsylvania legislature. In 1766 the German Friendly

Society of Charleston, South Carolina, was founded for the same purpose.

While the war years had brought the Atlantic migration to a standstill, a new

wave of immigrants was to be expected, particularly from Germany and

Switzerland, once the peace on the seas was restored. Being the only large

port near Philadelphia and being without any protective society for the

redemptioners, Baltimore would invariable be the next gateway for this abuse.

With wise foresight the leaders of the German community in Baltimore anticipated

such a development.

After recounting the story of the colonial immigration, the first chronicler of

The German Society of Maryland describes the reasons why the Germans in

Baltimore expected a renewed influx of their countrymen and what measures they

took to protect them from injustice: "Since the Revolution which was ended

by the Paris peace treaty of the 20th of January 1783 recognizing the

independence of the thirteen United Provinces, many more will migrate over here.

For the causes of emigration are still present in our great Fatherland:

limitation of religious freedom, restraint of conscience in manifold ways in

order to prevent the exercise of the natural rights of man, i.e., freedom of

thought and freedom of expression, injustice in courts, oppression by little and

big despots and impediment of gainful activity.

"In the same year during which the independence of the United Provinces was

recognized, the German Society was established to help needy countrymen.

In Philadelphia such a Society has been in existence for some years.

Baltimore-which thirty years ago consisted of but fifty houses, has now some

1800 beautifully built houses and next year will count 2000 of them-is vying

with its sister city in wealth as well as in all good works. Therefor also

the above mentioned Society was founded here. The inceptor of the same in

Baltimore is from Berlin: a gentleman by the name of Wiesenthal who for more

than thirty years has been considered the most skilled and philanthropic

physician in this place. The secretary of the Society is a Mr. John Conrad

Zollikoffer of St. Gallen, a cousin of the well-known clergyman by the same name

in Leipzig. The membership consists of merchants, teachers, artists, and

other citizens of German origin, all of the City or its vicinity. Several

of them have been elected overseers. Their principal duty is to assist

arriving countrymen financially and in any other respect."

Immediately after its founding in 1783, the Society published the following

statement to acquaint the public with its purpose and with the duties of the

overseers: Reasons which

have led to the founding of a German Society at this place for the benefit of

certain poor, newly-arrived or otherwise distressed Germans.

Considering the many hardships human life is subjected to and embittered by, and

observing how many of them could be-though not wholly remedied-at least

alleviated so much as to make them bearable, it is regrettable that love of

humanity has cooled down and the Samaritans who stand duly by their fellow men

are few. Not the least, however, among all the circumstances which require

the assistance to fellow men and the exercise of philanthropy is the case of

people who abide in strange lands and being ignorant of the national language

and custom, without means to support themselves, yea, often sick and weak, would

be exposed to greatest hardship if there were no philanthropist to look after

them and assist them. Such misfortune has so often befallen those

who emigrated from Germany to this occidental continent that it caused the

inhabitants of German birth and descent in the neighboring Pennsylvanian City to

establish a Society with the purpose of helping such newly-arriving countrymen

with advice and assistance. The success of this laudable enterprise soon

became evident and it assumed such importance that many hundred poor Germans

were assisted upon their arrival and enabled to settle as useful members in this

so richly blessed land.

Inasmuch

as it seems likely that within a short time from now many of our countrymen

might leave their Fatherland to seek improvement of their lot in this country,

the German Inhabitants of this City and its vicinity after due consideration

have resolved to follow the example of their brethren in Pennsylvania by

founding a similar Society in this City with the purpose of assisting not only

newcomers but all those who are in need. To this end they have resolved

and undersigned the following articles:

ARTICLE I

Should

vessels carrying German emigrants arrive at this City or its vicinity and should

any passengers be in want through sickness or otherwise destitute, the overseers

therefor elected will examine all cases in order to help such needy people.

They must particularly well investigate the cases of those who have not yet paid

their passage to protect them from injustice. They shall bring to reliable

people those who have to indenture themselves for payment of their passage.

They shall provide the sick with necessities and medicaments until their health

is restored. They shall provide burial at the expense of the Society for

those who die without leaving any means. Should such destitutes leave any

children, the overseers will endeavor to entrust the latter to the care of good

and reliable people and assure that they will attend school in order to receive

a Christian education.

ARTICLE 2

As

it may happen that newcomers who have paid for their passage but for lack of any

acquaintances be unable to carry out their trade and be therefore exposed to

want, as much assistance as possible should be accorded in order to enable them

to work in their trade or otherwise make an honest living so that they may repay

the amount spent for them. But only under the following condition: that

such needy applicants are otherwise honest people neither given to drinking nor

other vices in which case they would have nothing more to expect.

J.K. Zollikoffer, Secretary

Baltimore.

On the Frederick.com website, there is an article titled "History of Frederick County" by the Historical Society of Frederick, Md., which details the route taken by these mid-18th century German immigrants. It also details the lure that the proprietor of Maryland gave to attract these new immigrants:

Excerpts from the book by Thomas J. C. Williams...

In March of 1732 the proprietor of the Province of Maryland desired to attract settlers to the Northern and the Western areas of his territory, so he made a proclamation declaring special land prices and taxes for settlers.

While the early land grants were to English-speaking people from Maryland, and the earliest settlers came from nearby St. Mary's, Charles, and Prince George's Counties, a large part of the actual settlers of the land were Palatines from Germany. Most of the German speaking immigrants were spreading south from Pennsylvania. Commerce between the German settlements in southern Pennsylvania and parts of Virginia was common, and the main road between these areas was through this part of Maryland.

Long before there were any settlements in Frederick County, parties of Germans passed through it from Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, to seek homes in Virginia. The principal route was over a pack horse or Indian road that crossed the present Pennsylvania counties of York and Adams to the Monocacy where it passed into Maryland. Once in Maryland, the road passed through Crampton's Gap and crossed the Potomac at several fords. The first German settlement in Frederick County was as early as 1729 in the village of Monocacy, which was the first village beyond the lower part of Montgomery County in Western Maryland.

Monocacy was situated at or near the present village of Creagerstown. Here around 1732 the first German church, which was known as the Log Church, was built in Maryland. The Log Church later became the church of Creagerstown and then was replaced by a brick church a few rods north of the old site in 1834. There were several taverns there to accommodate travelers on the Monocacy Road, which was constructed by the governments of Pennsylvania and Maryland. Monocacy Road was an improvement upon the old Indian trail which was formerly used. The road went from Wright's Ferry in Pennsylvania to the Maryland line, then to the Potomac, and then on to the uplands of Virginia.

This group was called the Irish by the locals and the history books. However they were actually Scots/Irish who were also known as the Ulster Scots. The Scots/Irish tended to migrate towards the highlands of Frederick County Maryland in the more western parts of the county. In small groups, they also lived in the German communities of Pennsylvania, Maryland and Virginia.

The French and Indian War also known as the Seven Years War, began in 1755 with general disaster to the British cause and the American colonies. The plan was for France to take possession of the British area of North America and for her and her allies to divide the colonies up among them. In the early part of 1754 every Indian suddenly and mysteriously disappeared from Frederick County. The emissaries of France had been among them and had enlisted their aid in their scheme to take possession of the full Mississippi Valley. England was laying claim to virtually all of North America. However, the French had a well established colony at New Orleans, and they were steadily extending their influence northward through the Mississippi Valley. When the English government made a grant of certain privileges beyond the Allegheny Mountains to the Virginia Ohio Company, the French increased their efforts to establish a chain of forts from Canada to their Mississippi settlements. The object was to confine the English colonies to the Atlantic slope. The French had a long standing treaty with the Iroquois Indians, and the Iroquois were greatly feared by every other Indian tribe in the whole area, including Western Maryland. Thus the French and the Iroquois were able to intimidate the greater part of the Indian tribes of the area to make war upon the English colonies. All of the settlements of the western parts of Frederick County eventually came under attack. Since the Scots/Irish were largely in the area between the Indians and the Germans, they were the first to feel the brunt of the attacks. Then the colonists, including the Germans were killed, tortured and burned out. Monocacy was burned until just the old log Church and a few nearby buildings were left standing. The depredations suffered by the colonists were legendary and T.J.C. Williams goes into great detail in his "History of Western Maryland", so I won't go into it here. The war was won through the efforts of the colonial army with little actual help from the British regulars.

After the war was over, Creagerstown was laid out by John Cramer between 1760 and 1770 about a mile from the original settlement of Monocacy and a short distance north of the old Log Church.

As the tide of German immigrants increased, a more direct route to Western Maryland was established. The immigrants landed at Annapolis and later some at Baltimore. From there they traveled over the bad roads of that time to their destinations in the valley of the Monocacy. The Maryland officials early appreciated the value of the German settlers to the province and did all they could to encourage the movement, as the Germans were looked upon as a thrifty, industrious and God-fearing people who were a benefit to the community. From 1752 to 1755, 1060 German immigrants arrived by this route besides those that came in through Philadelphia and used the Monocacy Road.

According to research by Linda Zeoli into the German settlements in western Maryland:

Where Did They Settle?

![]() Western Maryland

Western Maryland

The first German immigrants came to America in the late 17th century. Encouraged by the religious freedom proclaimed by William Penn in his travels throughout Germany, a group of Mennonites crossed the ocean to settle in Pennsylvania. Decades later their descendants, as well as thousands more German immigrants, began to spread out from Pennsylvania into Western Maryland. They established communities like Frederick and Hagerstown.

In order to encourage settlement in these Western Maryland counties, Lord Baltimore made a special offer, in 1732, that those who came to Frederick County could own up to 200 acres of land without paying the usual tax. Few Germans took up his offer until 1744, when a land speculator named Daniel Dulany bought a large tract of land in Frederick County and sold 100 to 500 acre farmsteads, at very low prices, to about 25 German families. Dulany laid out a town on the eastern edge of this tract and rented lots to artisans, merchants and other tradesmen who would provide the goods these farm families needed. The town was named Frederick.

These German immigrants were a tightly knit group, although they lived on large, isolated farms. They may have come from Pennsylvania or traveled on a ship together, or even lived in the same communities in Germany. They came together through their church, held the same religious beliefs, spoke the same language, and turned to one another for aid and support in the Maryland "hinterlands." The fertile land provided for such diverse crops as wheat, rye, barley, and corn; orchards for apples and peaches; and flax for clothing (linen).

"By 1790, 86 percent of all Maryland Germans lived in the backcountry counties of Frederick, Washington, and Allegheny. They made up 44 percent of the total population of those counties." (Fogleman 1996, 8)

Friedrich Scheimer, son of Friedrich Scheimer

After arriving in the New World, the Scheimers went in varying directions. As was earlier stated, Friedrich Scheimer settled in the Chester County, Pennsylvania area. Friedrich was born about 1730 in Gersheim, and married Mary Magdelane Bachin (Bach) on 7 February 1752 at the Old Trappe Church in Trappe, Chester County, Pennsylvania. He died sometime before 19 September 1807 in Chester County. Some notes that I found on this Shimer from Allen R. Shimer's "History" are as follows:

According to Allen R. Shimer's "History and Genealogy of the Shimer Family in America," Volume VI 1946, p. 61:

DESCENDANTS OF FREDERICK SHIMER and MARY MAGDELANE (BACHIN) BACH

Frederick Shimer, with Michael, Daniel, and Adam Shimer came to America in 1749. They sailed on ship "Edenburg" starting from Rotterdam, September 15th, 1749. The marriage of Frederick Shimer to Mary Magdelane Bachin (German for Bach), was recorded February 7th, 1752 in the Church records of the Old Trappe Church, Trappe, Pa. The Augustus Lutheran Church, known as the Old Trappe Church, near Collegeville, Pa., was founded by Muhlenberg and is known as the oldest Lutheran Church building in America.

They settled in Chester County, Pennsylvania. The union was blessed with eleven children, seven sons and four daughters, Conrad, Daniel, Bartholomew, Michael, Frederick, John, Peter, Catherine, Elizabeth, Mary, and Barbara.

The copy of the LAST WILL AND TESTAMENT OF Frederick Shimer is recorded in Vol. I, page 53.

Friedrich Scheimer's name is found on a congregation list to raise money to build a new church for the St. Peter Lutheran Church in 1771, a year after that church split from the Zion Lutheran Church in 1770. The list has many of the congregation still using the Germanic spelling of their name, including Friedrich, and can be found at the following website: http://www.pa-roots.com/chester/church/lutheran_churches.htm.

The tabulated genealogy appears in greater detail in Allen R. Shimer's "History". I will be uploading my tabulated genealogy through the Personal Ancestral File program and will link that data on this page in the near future.

Again, according to Allen R. Shimer:

Although Frederick Shimer had seven sons and four daughters and nearly fifty grandchildren there is to date, as far as we know, but one (1) great-great grandchild bearing the name of Shimer and that is a girl, Miss Mildred F. Shimer, daughter of Herbert M. and Ellen J Shimer of Philadelphia, Pa.

In the seventh generation there is not a boy, as far as we know, bearing the name of Shimer, a direct descendant of Frederick Shimer, who came to these shores in 1749. This branch of the Shimer family is fast becoming extinct, as far as the name goes. There are still many, very many, descendants of Frederick Shimer, but they are not known by the name Shimer.

According to his will, Frederick and Mary Magdelane Shimer had seven sons and four daughters, Conrad, Daniel, Bartholomew, Michael, Frederick, John, Peter, Catherine, Elizabeth, Mary, and Barbary.

Michel Scheimer, son of Friedrich Scheimer

Michel (Michael) Scheimer settled near his brother Friedrich in the Chester County, Pennsylvania area. It is unknown at this time when he was born, but it is presumed that he was born in the Gersheim area of Germany as well as his father and brothers.

According to Allen R. Shimer's "History and Genealogy of the Shimer Family in America," Volume VI 1946, p. 81:

DESCENDANTS OF MICHAEL SHIMER and MISS ASH

MICHAEL SHIMER, who with Frederick and Daniel Shimer came to America in 1749. The sailed on ship "Edinburg" starting from Rotterdam, September 15, 1749.

Michael Shimer married a daughter of Adam Esch (Ash) of Coventry Township, Chester County, Pennsylvania. he settled on a tract of 270 acres of land on the Schuylkill River in Vincent Township, Chester County, Pa., where Spring City, Pa., now stands.

He died young leaving one son, Adam, and three daughters. One married Jacob Keller, another married Henry Hipple, and the third married Mr. Sypherd.

The tabulated genealogy appears in greater detail in Allen R. Shimer's "History". I will be uploading my tabulated genealogy through the Personal Ancestral File program and will link that data on this page in the near future.

Daniel Scheimer, son of Friedrich Scheimer

Calhoun County Lines & Links -- The George Washington Shimer Family, by Colvin W. Snider. December 1979.

Daniel Shimer was a German immigrant who come to America in 1749 from the Palatinate section of the Rhine Valley. Daniel, a blacksmith by trade, left Rotterdam with his two brothers, Michael and Frederick, on September 15, 1749. After the S. S.Edinburg (sic) put into port at Portsmouth, England, it set sail across the Atlantic for Philadelphia. The ship register carried them under the name spelling as Scheimer. The record of the immigration of the three brothers is recorded on page 287,Pennsylvania Archives, 2nd series, Volume 17.

Daniel

Shimer left his two brothers in the Philadelphia area and settled in the

frontier community of Frederick in the Colony of Maryland (Frederick County was

formed in 1748, split off from Prince George County).

The year before he had left the Palatinate, the proprietor of the

Maryland Colony, Lord Baltimore, had advertised in that province for immigrants

to come to Maryland.

Daniel Shimer married and raised five children: Jacob, James, Ezekiel, Susanna, and Elizabeth. There was a Reform Congregation in Frederick, which was the center of German immigrant life.

Daniel Scheimer made his was to the area of Frederick, Maryland soon after arriving in America. He most likely traveled by old Indian roads, like the Monocacy Road, into northern Maryland.

Daniel Scheimer's tabulated genealogy appears in greater detail in Allen R. Shimer's "History". I will be uploading my tabulated genealogy through the Personal Ancestral File program and will link that data on this page in the near future.

This is the time frame that Daniel Scheimer made his home in and around Frederick, Maryland. The German community had strong ties in this area, with commerce and contact maintained with the larger German communities to the north in Pennsylvania. James Shimer, who was as far as we know Daniel Scheimer's youngest child, was born in 1752, three years before the start of the French and Indian War. Having fled his homeland in the Palatinate only six years before, Daniel Scheimer again found himself on the front lines of a European war, brewing over the horizon of his new-found home. Western Maryland and Pennsylvania played a large role during the upcoming war. From a pamphlet marking the 250th anniversary of Fort Cumberland, some greater detail is given as to what led to the war between Britain and her colonies in America and France:

The issue was the land west of the Mountains, the Ohio Country. Both Great Britain and France claimed it, but by the early 1740s had done little to assert their claims. It was Indian country, visited only by an occasional French trader. The two countries were bitter rivals, and in the past 60 years had fought three wars. The last had ended in 1748, but nothing had been settled. The rivalry remained.

The key to the Ohio Country was the spot where the Allegany and Monongahela Rivers met to form the Ohio River. Known as the Forks of the Ohio, it is the location of present-day Pittsburgh. Travel in the wilderness was easiest by boat. Whoever controlled the juncture of the three rivers would control region and the lucrative fur trade.

In the late 1740s, British merchants began to filter into the region to trade with the Indians. In 1749, a group of prominent Virginians and Marylanders obtained a charter for a company to develop the Ohio Country. It was known as the Ohio Company. Plans were made to develop trading centers and to settle 200 families in the region.

The company moved quickly to put its plans into action. First, a fortified storehouse was built at Wills Creek, the site of present-day Cumberland. In 1751, Christopher Gist was sent explore the back country and a road was surveyed. In the spring of 1752, company officials met with local Indians at Logstown and obtained and agreement for a trading post at the Forks. That same spring an additional storehouse was built at Wills Creek. In the fall, another fortified storehouse, known as Fort Red Stone, was built some 37 miles from the Forks. The next step would be a fortified storehouse at the Forks itself.

In July of 1752, the new French governor, the Marquis Duquense, arrived with orders to drive the British from the Ohio Country. He immediately set to work shoring up Indian alliances and recruiting soldiers. Forts were to be built along the waterways leading to the Ohio Country, and by the fall of 1753, three had been completed. A fourth, at the Forks, was to be completed in the spring of 1754.

The British scrambled to meet the challenge. The royal governors were ordered to do what they could to keep the French from the Ohio Country, but primary responsibility fell on the Governor of Virginia, Robert Dinwiddie. Detailed instructions for dealing with the French were issued. including an order to build a fort at the Forks.

In October of 1753, Dinwiddie dispatched 21 year old George Washington to Fort Le Boeuf with a letter warning the French to leave the Ohio Country, which was politely refused. The governor then set to work recruiting forces and assembling resources needed to secure the region.

In February of 1754, a 40-man building party was sent to the Forks to build a fort. At the same time, efforts began to recruit colonial troops to man it. On April 2, the first contingent of 160 Virginians, commanded by George Washington, set out for the fort. Reinforcements were to follow as soon as they could be assembled.

As the Virginians struggled through the wilderness, a force of about 500 French troops arrived at the Forks and the newly completed British fort. The French sent the 40-man building party home and set about building a larger and stronger fort. It was named Fort Duquense.

Washington halted at Great Meadows when he found out the French were in control of his destination. After attacking a French scouting party on May 28, he settled in to wait for reinforcements. While waiting, the position was fortified with trenches and a stockade and named Fort Necessity. Reinforcements arrived, and by late June, Washington had some 400 men.

Meanwhile, the French reinforcements arrived at Fort Duquense. With his numbers substantially increased, the French commander sent a force of 700 to deal with Washington. Fort Necessity was quickly surrounded, and after a day of firing, the French offered to talk. By this time, about one third of the colonials had been killed or wounded. The French agreed to let Washington's force go, and on July 3, the colonials marched off for Will's Creek.

News of Washington's defeat quickly reached Williamsburg and London. The impact was electrifying. In London, it was quickly decided to settle the French matter once and for all. A large force of British and colonial troops was to be assembled for an assault on New France. A single commander would manage everything. The man selected was General Edward Braddock. He was to have authority over all the royal governors, and was, in effect, the Viceroy of America. The plan finally settled upon was a four-pronged attack on different parts of New France, including an attack on Fort Duquense.