Photos and comments courtesy of:

Phil Garey

During his tour in the Army Air Corp 1944

My High School Grad pic - aged 17 (May 1943)

My Enlisted days with the Army Air Force

World War II, Eighth Air Force, 4th Wing,

3rd Division, 94 Group, 331st Squadron

8th Army Air Corp--94th Bomb Group

Finishing basic training. (Nov 1943)

*HUTS, BARRACK, AND TRAINS*

Fresh out of Gunnery School at Las Vegas, I was assigned as a gunner

on Jim Cumming's crew at Salt Lake City AAF, in February 1944. Jim came

down to my barracks and introduced himself as a pilot and said that he

was from Richmond, California. I was from El Cerrito, which adjoins Richmond,

and he had noticed this while going through records of unassigned gunners.

He asked me if I wanted to be on his crew and I fell over myself telling

him that, yes I sure did, Sir! I had never ever talked with an officer and

was completely awed that one of them would talk to a PFC. So was everyone

else in the barracks! I was already a celebrity of sorts for having saluted

the civilian Fire Chief, mistaking him for an officer!

B-17F [left] and B-17G [right] tailguns.

That barrack was a miserable place to live, one of those

20X50 single story, temporary, war built, freezing in winter, roasting

in summer huts. Heat was provided by a couple of coal fired pot belly

stoves, and they were completely inadequate for that time of year.

But on the other hand, maybe they were adequate. Since there were

probably fifty or so men in there with me, with bunks double decked

and about 18" apart, the body heat alone must have helped a lot.

Latrines were in another building some distance away, and you quickly

learned to get everything done in one trip. Shit, shower, and shave in

the morning, and one last trip before sack time at night. It was cold!

At any rate, I was only there for a few days, met the rest of the

listed members of "Cummings Crew," which included Cpl. Ed Herbert,

the Crew Chief, Cpl. Bob Herald, Radio, Cpl. Al DeWolf, Armorer,

and PFC's Ralph "Pappy" Painter, and Steve Wasser, "career" gunners,

like myself. We got on a troop train to Dyersburg, TN, and spent

the next five or six days getting to know one another better.

My crew in Tennessee just before going to England

in WWII. L to R: Bob Herald, Ralph Painter (Pappy),

Phil Garey, Ed Herbert, and Al Dewolf. (1944)

World War I had its "40 et 8," but we had the troop train, which

consisted of ancient Pullman cars. The assignments were that two

men bunked together in the bottom bunk and one singled it in the

top. Being 6'1", I was always given a top bunk. Can you imagine

sleeping arrangements like that in today's world?

Toilet facilities were standard Pullman, the only problem being that

there were too many men (or too few toilets!), and the food problem

contributed to that. We were fed from a makeshift kitchen in a baggage

car. Food was some kind of rations cooked over makeshift coal fired

stoves. We'd go down a line holding our mess kits out and the cooks

would slop food in it. This on top of that, take it or else. We'd get

our mess kit filled, then a cup of almost undrinkable coffee, and went

our way back to the Pullman, wolf it down, then wash it off the gums

with scalding coffee. I already knew that there is no possible way to

drink hot coffee out of a mess kit cup without burning your mouth.

The coffee never cools down. One second it is burning hot and the next

second it is ice cold, there is no middle ground.

At any rate, as soon as we finished our meal we headed back to the

kitchen car to wash our gear. They had set up a series of garbage

cans on fires burning on a brick floor and the procedure was to scrub

out the mess gear in the first one, which had GI soap dissolved in

it, then rinse and re-rinse in the garbage cans that followed. Maybe

the first guy got his mess gear rinsed but after that there was always

a soapy residue. This brings me back to the toilet problem. Every one,

depending on the nature of his internal workings and/or the amount of

soap on his mess kit, was either constipated or had the big "D!" And

there were simply not enough toilets!

By the way, there was a touch of luxury on these troop trains. They had

the regular Pullman Porters assigned and they swept up and made the bunks.

We were led to understand in no uncertain terms by the military troop train

crews, that we were expected to tip the Porters. So we did, to the tune of

about $5.00 each. A tithe, since we were earning $50 a month now. I always

suspected that the military train crews got a little kick back there.

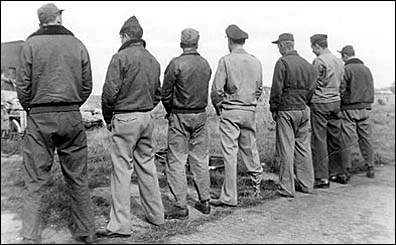

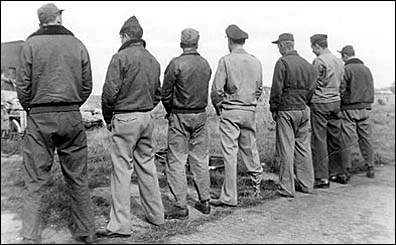

Re enactment of the last thing a crew did before

leaving on a mission. Me on left (1944)

When we got to Dyersburg AAF, Tennessee for our Combat Crew Training,

we were assigned, by crew, to a new arrangement in quarters. Some war

profiteer had gulled the Army Air Force into buying prefabbed huts.

These were of simple plywood construction, about the size of squad tents,

joined together in threes. Each hut had a pot bellied stove in each

segment and two windows with screens but no glass. The windows were

covered by a shutter that could be propped open with a stick. Lighting

was provided by a single unshaded bulb hanging in the center of each hut.

Each crew of six men was assigned to a hut, and that's where the crew

really became friends. In such close quarters you either became friends

or you were off the crew. The military base siting committee, who selected

the most miserable locations all over America to put bases, had taken

particular care to locate this bit of deep mud, and the huts were located

in the deepest part of the mud. The official Washington position was the

more miserable, the better. Cleaning was a constant problem and we had

all the typical inspections that you'd find in a peacetime army post.

The latrines were as usual, located in a separate building some distance

away. Because of the mud, a trip there inevitably resulted in shoes or

shower clogs covered in mud. The floors were covered in mud no matter how

often those on latrine cleaning duty cleaned them. Then of course, are huts

had a layer of mud, no matter how often we scraped it off and mopped up.

Just as the rain stopped and the mud began to crust over, we finished our

training, and headed west on another troop train. This time we were headed

for Kearney AAF, Nebraska, to pick up a new B-17. These trains had one big

difference, a new (to me) type car. They were steel freight cars with

windows cut into the walls and rows of bunks, three high, along the walls

with a central aisle. Each was especially constructed with squared off wheels

so they would ensure the ordinary soldier to pain and prepare him for the

rigors of war. Still had the ubiquitous Porters, who demanded their tip!

Meals were the same, garbage! The new trains still had the same old cook

cars, and the food that went in came right back out the other end. And as

the computer people say in the modern age, Garbage in, Garbage out.

At Kearney, where we had come to get a briefing on aerial warfare, by

men who had never been outside of Nebraska, we were assigned a brand

new, shining B-17G. We lived in a standard two story 20X100 barracks,

with as many as 150 men assigned. We never knew who was there because

crews came and went quite rapidly. We were only there a few days, but

wallowed in the luxury of indoor latrines, with hot showers! I

remember the food at Kearney as being quite good, probably as a result

of two things. The food at Dyersburg, in the special air crew mess hall,

was on par with the worst of basic training food, and then we had just

gotten off a three day trip on a troop train!

One special bit of training there got me in to trouble. It was first aid,

and the instructors used rubber body masks with simulated wounds on them,

complete with simulated blood and holes. They put one of these on a crewman

and told us that this man had been hit by two 50 caliber slugs in the chest.

What would be the proper treatment? We stared at him with wonder. No one

answered. He finally called on me and I didn't know what to say. I finally

stammered out something about putting a band-aid on each of the wounds! The

instructor blew his stack! What did I mean Band aids? Was I dumb enough to

think that applying band-aids to serious wounds like that would help? I got

mad and asked him if he really believed that while flying in an airplane at

30,000 feet, in freezing cold, and wearing all our protective gear, we could

apply any kind of first aid that would help a man who had been hit in the

chest with two 50 caliber slugs! Oh man, Oh man! Was that ever the wrong

answer to give! I never did get the court martial I was threatened with, but

I was one scared 18 year old brand new buck sergeant till we left Kearney!

*DYERSBURG AAF, TENNESSEE*

Dyersburg, Tennessee, one of the most ill-conceived Army Air Bases of War II,

was situated in Western Tennessee, near the Mississippi River, surrounded by

swamps, beset with rainy weather, and seemingly floating on a sea of mud.

The nearest village was called Halls and the local town was Dyersburg,

county seat, complete with a town square and a courthouse.

To an aircrew member, both Halls and Dyersburg were complete

mysteries. I was in Halls once and Dyersburg a half dozen times,

mainly to catch a bus to Memphis. I remember dour men with old hats

sitting around town, even some of them whittling away at a stick,

cigarette or pipe hanging from the mouth, or maybe a drool of brown

tobacco juice, and with little piles of wood shavings around them.

There was nothing there to attract us and the peculiar liquor laws of

the south prevented us from searching for the jug of happiness. But

Memphis! That was the storied home of Jazz, alcohol and beautiful women!

None of the enlisted men, and very few of the officers had cars.

We'd get a ride in a G.I. bus or on the back of an army 6X6 truck

and we were on our way to town. The first time Cumming's Crew, or

at least the enlisted men on it, headed for town, we walked. It was

our first free day after processing into Dyersburg Army Air Field.

We walked out the gate and onto the local highway and headed to Halls,

hoping to take in the local scene, not knowing that there was nothing

in Halls. We had walked along the road hoping to hitch a ride, but in

those wartime days, and out in the farm country like that, vehicular traffic

was mighty thin. The road was bordered by a swamp and there scattered humps

with trees upon them and a few small houses set on islands of ground above

the level of the water. We trudged along with B-17s taking off just a few

feet above our heads and we gawked at each one like fliers will always do.

They were literally only a few feet above us, maybe thirty to fifty feet.

We were watching one bomber thunder over, when suddenly the ear-bursting

noise ceased, the giant aircraft headed for the ground and crashed into

the swamp beyond the fringe of trees! The six of us quickly decided that

two of us would head back to the base and the other four go for help.

Herb and I headed at a dead run for the gate, about a half

mile away, where we breathlessly informed the MP gate guard

of the accident, but the rescue vehicles were on their way.

Meanwhile, the rest of the crew were already at the scene. They had

gone to one of the small houses at the scene and commandeered a small

row boat. The owner refused to tell them where the oars were, so they

ripped boards off a fence and paddled out into the swamp a few hundred

feet, found the wrecked aircraft and attempted to rescue the crew.

Unfortunately, the crew was dead. They found a floating parachute and

pulled it up to the boat, but the attached crewman was dead. The rescue

crews arrived on the scene and Cumming's crew left and headed into Halls.

What an introduction to Aircrew training! And how calloused we were!

Later we were told that the cause of the accident was Pilot's Error.

In this case Co-pilot's error. Following the check list on operation,

as the plane lifted off the ground, flaps down and wheels were lifted

up, the Co-pilot, reading from his chart, reached over and closed 4

switches. Unfortunately, he missed the four Booster switches that gave

maximum take-off power, but caught the four nearly identical switches

located near his mark. And unfortunately, these were the battery switches,

which cut off all electrical power to the four engines! The engines stopped

abruptly and the plane crashed before anyone understood what was happening.

It was the first time the wrongs switches had been thrown,

but later a modification was made to the B-17s which moved

the site of the battery switches to another location. Too

late for those ten dead men and probably others before them.

*PROCESSING*

I mentioned processing. Processing was the procedure for checking in

and out of a base. Everything was done on an organized basis and

in-processing typically took three days and out-processing the same.

I think I once set a record for in-processing and out-processing. I

processed in at Salt Lake AAF on a Sunday, got my crew assignment, visited

my Grandmother in Salt Lake City and finished out-processing the next Sunday!

At any rate, you started at 0800 and marched to the processing center to

begin going through a check of everything that had to be done. You waited

endlessly in line for everything while a long series of clerks and

orderlies did their duty. They checked all your personal records, making

certain that everything was correct and up to date. No matter that you may

have just had an out-processing at your previous station three days

before. This was here and that was there! So you stood in line after line,

leaning against walls, sitting on steps, shifting and shuffling, longing

for a coke or a candy bar, endlessly and aimlessly talking with one another.

Oft times the clerks would go for lunch and just leave the men waiting.

Or they'd go for a break and we'd wait... and wait.... and wait.

Another part of processing was a clothing check and you had to bring

all your issue clothing in your A and B barracks bags, with the

addition that we were now carrying our flight gear in two more bags

and the B-4 bag. We were so heavily laden we could barely stagger

along the streets from the barracks to the clothing check warehouse.

If you were missing some item of clothing you signed a Statement of Charges,

were reissued the item and the cost was later deducted from your pay.

One of the odd things about my week of processing at Salt Lake AAF,

was that I underwent two complete physical examinations! And none

of the processing hospital orderlies thought there was anything

unusual in my record all being done within the week by the very

same people! As someone twice said, That's the army for you!

*DIRTY CLOTHES FOR NEW!*

One peculiarity I learned about clothing issue, but later on when I

was a sergeant, was that they would replace damaged or worn items

without charge. Not even a question. So what I would do when I ran

out of clean underwear was to make trip to supply and throw the items

on the counter and say, These are worn out, give me replacements. They

never questioned me and I walked out with six sets of clean underwear.

Most of the time though I washed my clothes in the laundry tub in the

latrines and dried it by stringing it around my bunk, as did everyone

else. Wool shirts and Khakis were sent to the laundry, and a week later,

if you were lucky, you picked up clean clothing and that was it. No charge.

The base laundries had special high tech button smashing

machines. We knew this because at least one button on every

shirt or trousers was broken. In those days we had button up

flies on trousers so there were a lot of buttons to smash!

*POST EXCHANGE*

Every base had a Post Exchange or PX as it was called. They weren't

like the military Exchanges of today, huge department stores with an

almost unlimited range of merchandise. They were small shops where you

could get the necessities of life. Cigarettes, cigars, stationary,

prophylactics, candy, souvenir pillows inscribed MOTHER, and so on.

Pens, pencils, cigarette lighters, and a few other items, but most

importantly, a beer garden was always attached. Here you could get a

beer for about 10 and a coke for 5. They were noisy, crude rooms with

tables and a few chairs and benches. The RA (Regular Army) old-timers always

had the chairs, and the AUS or wartime reserves, sat on the benches. I didn't

drink and the smoke was thick. There always seemed to be a belligerent who

wanted to fight, so the best thing was just to stay out of them.

The Regular Army men were people who had been in service as Regulars

before the war. Some after many years of service had achieved the

rank of PFC (Private First Class) or Corporal.. They sat there with

their pot bellies, ruddy faces and were a class to themselves. I

could never figure what kind of military jobs they had because they

were there as soon as the Open sign went up on the door and stayed

all day. They never spoke with anyone but themselves, certainly not

to an AUS PFC and especially not to an aircrewman!

*PAYDAY & PAYROLLS*

Payday came once a month, on the last day of the month or the

first weekday afterwords. When I first entered the service I

found payday was an ordeal that civilians never had to face.

If they had they'd have resigned from being civilians.

Payday finally came around and we prepared ourselves according

to the instructions of our D.I. Fresh haircut, clean shave,

Class A uniform, shoes spit shined, the best we could look.

The procedure was to get in the payroll line, in alphabetical

order, a chore in its self. Then we found that Ras came on

the front of the payroll and were paid first. They just strolled

to the front of the line, sloppily appearing, gave a salute,

mumbled their name and the officer counted out their money,

handed it over and they strolled off to the beer garden.

Now we AUS men, spiffed up as well as we could, had to approach

the table Salute, and recite our name rank and serial number.

I was Sir, Pvt. Garey, Phil D., 19149129, reporting for pay Sir!

The armed sergeant standing in front of the table would repeat,

Private Garey, Sir! If you made an error, you were sent to the

end of the line and awaited another chance. If the Sergeant or the

clerk was in a bad mood, they would redline you, that is, draw a

red line through your name and you were out of luck until next month.

And this happened often enough to make you want to do it right the

first time! The NCOs also inspected your appearance and your

bearing. If it didn't meet their standards, you were redlined.

Some poor sods, despite all night rehearsals could not

say the required line without error, through nerves or

maybe stupidity, and they were dismissed with contempt!

Seated at the table was an armed officer and an armed finance clerk,

with the long pages of single spaced typewritten names, ranks, serial

numbers and the amount each man was due. You stepped to the table and

the clerk pointed out your name and you signed on the dotted line. The

pens were the common type, and you dipped it in ink and signed. Woe be

upon you if you made a blot or splash of ink! You were in deep trouble!

The officer had a cash drawer and would reach in, count out your

money, hand it to you, then you counted it out, then you saluted,

did an About Face and strode away, stuffing the money in your pocket.

My first payday I got $50.00, less $6.11 Government Insurance, and

less a sum for laundry, about $40.00 then I had to run the gauntlet

of the first Sergeant, the D.I. and the loan sharks, old time RA

men. They collected a dollar or 2 for various vague things. The Loan

Sharks were there to collect from men who had borrowed from them.

A $5.00 loan would pay them $7.00. They had concessions and were

backed up by the First Sergeant and the other regular army NCOs.

*THE REALIZATION STRIKES!*

One afternoon I was in the barracks, and alone for the first time.

After a bout in the hospital suffering the aftereffects of my shots,

I had returned to the squadron and all the others were out doing their

basic military training. I sat down on my bunk and fell into a very

despondent mood. It dawned on me that I was really in the army and it

looked as though I would be in it for the rest of my life. I had signed

up when I volunteered for the USAAF for a period of The Duration of the

War Plus 6 Months. Holy cow!, this was forever. This was early October,

1942. The NAZIs we still in control of most of Europe, the Japs were

running wild over the Pacific. The Allies had had one or two minor

victories. They had invaded North Africa and in the Pacific, Guadalcanal

looked like we were making a start in the Pacific, but where was the end?

It seemed endless and I'd be an old man before it was over!

As I sat there with my head in my hands, the Barracks Chief, a Corporal

whose sole duty seemed to be in the barracks when no one else was present

and to maintain order at night, approached me and asked me what I was

doing in the barracks. I told him I had just been released after 4 days

in the hospital. He told me that he had been talking with my D.I. and

knew that I knew all the drill and physical training aspects of Basic.

How would I like to be the Assistant Barracks Chief? I would be in charge

of the barracks when he was absent and make sure that everything was safe.

I'd be excused from all basic training except rifle range, parades and

long marches! Wow, and Yes Sir! So my first promotion came through.

From then on, I would march to breakfast with the squadron, sometimes

acting as the squadron leader and shouting out commands to move them

on and to the mess hall. After breakfast, we'd return to the barracks,

and prepare for the days training. Unless we were going to the range

or on a march, I was through for the day! When all had left, I would

sit and read, polish my shoes or whatever struck my fancy. About 0900,

the barracks Chief would appear, announce that he would be back,

and leave. I later discovered that he would go to the mess hall for

a late breakfast with his cronies, then they'd all head over to the

PX for the 1000 opening of the beer garden.

In the evening, when the troops had returned exhausted from

their training, there I'd be lazily greeting them. When they

were cleaned up and ready, off we'd march to the mess hall for

supper, and I'd often do the marching. Thinking about it now,

it's a wonder that there wasn't an unfavorable reaction against

me but it must have been that they were to tired to care or envy

me or that they just figured, What the hell, he's a lucky one!

*MEMPHIS, THAT WONDERFUL TOWN!*

When we got a little time off from flying training at Dyersburg,

we'd all, the six of us on Cumming's crew, would we'd head off

for Memphis. What a City! We'd get a truck or bus into town and

then the Greyhound bus for the big city. Sometimes we'd hitchhike,

but that was a chancy way to travel because of the very limited

wartime traffic. Sometimes a farmer would give us a ride in the

back of his old flatbed truck, but that was only part of the way.

Then we'd have to try for another ride or catch the bus.

Once safely in Memphis we'd head for a fleabag hotel. These

usually had the reception desk up a flight of stairs and

invariably there was an old, old man on the desk. We'd generally

get 3 rooms, sleeping two to a bed. Bathroom was down the hall.

We'd get out on the street hunting for a bottle. If we found a

liquor store open we'd be forced to buy 2 for 1. This meant

that if we wanted to buy a bottle of whiskey or gin we had to

buy two additional bottle of some otherwise unsaleable goods.

Maybe a quart of Sloe Gin and a bottle of Creme De Menthe, or

some other abomination. Whatever it was we'd all chip in and

pay for it. Then we'd head out for the bars and the Jazz, and

the mythical women. I say mythical women because we were

always going to find some absolutely stunning girl and we'd

be happy into eternity! Needless to say, we never did! Either

we'd lose interest after looking at the rough stuff in the

bars or we'd get engrossed in the Jazz. There was some

fabulous music in Memphis in those days. My ear were more a

tuned to Big Band Swing, but I soon grew to love Jazz. Bob,

the radioman, was a musician and he'd often sit in with the

band, while we sat at our table enthralled. There many great

Negro musicians playing, both in white and Negro bars.

We'd didn't care, and Bob just wanted to play!

I'd usually have a drink, get sleepy and head back to the Hotel. I

was always tired in those days and wanted a real bed and above all a

long hot bath! So when I got to the hotel, I'd get my towel and head

down the hall to the bath. I'd run the tub full and hot and lie back

and soak. Ah Heaven. Often I'd fall asleep and waken to either a cold

tub or someone pounding on the door wanting his turn at the tub!

On one of these trips, Pappy met a lovely young woman named Marie. He

had a suave look about him. Reddish hair, a red mustache and quite a

handsome man. Pappy had been married a couple of times but they didn't

stick. He was a native Los Angelinian, and had been a parachute packer

for Standard Parachute Company. As an incentive to keep the quality of

their work up, his supervisor would come along the packing tables and

pick up a parachute that the worker had packed and say, Come on its

quality control time. Off they'd go to the local airport, up into the

sky and then the packer would jump with the chute he'd just packed!

Just part of the job. Pappy claimed that one time he'd been blown

adrift by the wind and had landed on the deck of a U.S. Navy Cruiser!

Anyhow, Pappy met Marie and they fell in love. Marie lived with

here grandmother, Mrs. Gray, a delightful elderly lady. Their home

was a beautiful old, slightly run-down house, quite large. We often

would meet there, taking food from local store and Mrs. Gray would

prepare us a meal and we were always welcomed. Sometimes we'd sleep

there, sprawled across the floor of her sitting room or on a sofa.

I corresponded sporadically with Mrs. Gray for several years.

Pappy married Marie and they lived together happily for a short

time, but were divorced shortly after the war when Pappy had

returned to the states. But it was a romantic interlude in our

lives at the time and I, for one, thought it would last forever.

*PEABODY HOTEL TEA DANCE*

One quiet Sunday afternoon, I had been separated from my crew and

wandered around Memphis at ends for something to do. I came across a

beautiful hotel, The Peabody. I'd never been in such a classy place and

entered rather carefully. It was just swell! I found a sort of ballroom

where I could hear music coming. I wandered in and there were all these

people chatting away, dancing and sipping from cocktails. I though, So

this is what I've been missing and looking for all over Memphis? I

sauntered over to the bar and ordered a beer. The bartender nodded. I

soon discovered that he had nodded at a couple of bouncers. I found this

to be true when these two giants grabbed me by the arms, frog-marched me

to the door and pointed out a sign reading, "Officer's Tea Dance! Then

I was thrown out the door and got the hell out of there. What a surprise!

On another trip to Memphis I got drunk for the first time in my life. We

had picked up a 1 for 2" pack of liquor and had a bottle of southern

Comfort. This was a sort of sweet syrupy tasting drink and I tried it

and liked it. We had also bought bottle of Port wine. I found I liked

it too. I was alone in the hotel and passed out. I awakened in the

morning, found I was alone and had been sleeping on the floor.

I realized I was sick and late. If I didn't leave quickly I knew I would

miss the last bus to Dyersburg that would get me to the airfield before

my pass expired. I buttoned up my coat, ran to the bus station and jumped

on the very crowded bus. No seats available so I had to stand, hanging

onto a strap. It was hot so I unbuttoned my blouse and noticed that the

crowded bus was becoming less crowded for me as the others edged away

from me. I was still drunk and I stunk! About half way on the two and a

half hour trip I was nodding, fighting to stay awake and looked down at

my chest. What a mess! During the night I had apparently vomited on my

shirt and the red wine stain was very smelly and very ugly! Now I

understood why people were edging away, and giving me such nasty looks!

I managed to survive the trip, though utterly humiliated! We arrived in

Dyersburg and I caught a truck out to the base. I quickly cleaned up,

changed clothes and went up to operations, wondering where the crew was?

I quickly discovered that we were scheduled to fly a surprise training

mission. Jim came in and asked me where the crew was. I didn't know and

told him so. Since the officers where there, they borrowed a radio operator

and an engineer, and we took off. It was a navigation cross country

training mission and we really didn't need the other gunners. It was also

ne of the most horrible flights I've ever suffered through. I was so sick

I thought I'd die. Out of pride, I didn't throw up, but I was sick! My head

hurt, my gut hurt, I had diarrhea, I couldn't think and I wanted to die!

The mission was finally over and we landed. Jim was visibly angry that his

crew had missed the flight. He apparently got chewed out by his superior and

robably got downgraded on his record for our absence. He never said it

aloud, but told me to have the crew report to him as soon as I found them.

That night they straggled in, hung over, dirty, tired. I gave them

the bad news and they asked, Do you think he wants to see us now! I

assured them that he did so they quickly cleaned up, and we marched

up to the Bachelor Officer Quarters. I went in and knocked on Jim's

door and told him the crew was downstairs. He told me to get them

in the lounge and have them at attention when he walked in.

When he came in, he was angry, but controlled. He simply said you

have let me down as a crew and that it had better not happen again.

He turned and walked out. We were flabbergasted and felt like utter

useless fools. We left and never missed another formation or flight

of any kind. We trained and studied and worked. Jim never mentioned

it again and neither did we! It was the one and only time I have ever

seen Jim angry and I knew him for 44 years until his death in 1997.

*ONE LAST TALE FROM DYERSBURG!*

Herb had gone home for a rare weekend in Ohio and managed to bring back

his car. This was indeed a rarity for an enlisted man! Even most of the

officers didn't have cars with them. We moved so much and when we came to

Dyersburg everyone knew that we'd be there about 2 months and then overseas.

Very few of the married men had their wives with them, officer or enlisted.

Anyhow, herb had his car and we took off for a quick trip to Memphis.

I don't remember if we ever got there, but anyhow, somewhere along

the line we had a few drinks and headed back in Herb's Ford. It was

a very foggy night, that dense low fog that envelops the Mississippi

River area sometimes. We were unsure of the road and didn't know

where we were. The drinks had their effect too.

We stopped and talked it over and agreed that it was best if we pulled

over to the side of the road and waited out the fog. Herb steered the

car over to the side and we promptly fell asleep. Once in awhile I'd

wake up hearing the blast of a horn or the screech of tires.

When dawn broke, we awakened and found that we were parked on the outside

lane of a four lane highway! That was the sound of horns and screeching

tires... cars or trucks avoiding us! Well, I guess we were being saved

for the war against Germany, because we had survived that bungle.

Me at tail of B-17 Flying Fortress. (1944)

At any rate, after a few days there, we took our sparkling new B-17G, and

flew from Kearney to Grenier Field, NH, and spent three days in a crew

transient barracks, which was not bad. I remember going through a spit shine

barracks inspection there, by base personnel, on the last day before we went

overseas. I guess they wanted to see if we were clean enough for combat.

We got as far as Gander, in New Foundland and waited a few days for

whatever officers did in those days. That's what enlisted men usually

did, wait for officers to get the inside skinny, then pass little bits

of it on to we GIs. Usually it was very abbreviated. They would spend

hours in a briefing then come back and tell us, "over there."

We amused ourselves at Gander with aircraft guarding, probably from

the hoards of ladies who lined the fences, and getting in line at

the NCO Club. They had two lines. One for beer, Ruperts Knickerbocker,

and the other for Seagrams 7 Crown. Or maybe it was 3 crown. 10 cents

a beer and 10 cents a shot. The system was to get in the beer line

and buy a beer, then go around to the shot line and sip the beer while

the line moved. When you got your shot you threw it down, chased it

with the last of the beer, and went back to the beer line.

There was no place to sit and you could only buy one shot or one

beer at a time. I think this was due to a policy set forth in

Washington to keep enlisted men from acting like enlisted men.

Anyway, it didn't work. When you could no longer negotiate the

lines, a buddy would drag you outside. There you bent over

facing east and prayed. If you could get up, back in you went!

I and a crewmate, Steve Wasser, were walking around the base on

a sunny, but very cold May day. We found a little lake, with a

little dock and a couple of row boats. It was the bluest lake

I'd ever seen and Wasser and I decided that we needed a swim.

We stripped and dove in. I stuck about half way in, it was

so cold! We turned blue in a second. Wasser claimed that,

although he dived in head first, he got stuck when the water

was about half way up his body and then he miraculously twisted

back on the dock, and only his arms got wet! It was that cold.

We decided to go back to the NCO Club, where a man could be safe.

Photo of 94 BG B-17 over wheel at Bury St. Edmunds. (1944)

We had an amazing assortment of quarters in our tour in England in 1944.

They ranged from the sublime to the ridiculous, and some of them weren't

that good. Our crew landed in Northern Ireland at Nutt's Corner, near

Belfast on May 25, 1944, fresh from a dead on navigated trip from

Newfoundland, courtesy of Lt. Joe Toeniskoetter, the world's best navigator!

Our brand new B-17G was promptly taken away from us and we were shuttled

off to a tent city where we were accommodated overnight in a large squad

tent. It was completely furnished with canvas cots and that was it. We

had been advised to leave our baggage in the aircraft where it would be

safeguarded by the ground crews, but Ed Herbert, the Flight Engineer

wouldn't hear of it and we reluctantly lugged all our baggage, flight

gear and all to the tent. The only thing we left was a few shopping

bags of food and one large sack of fresh oranges, which we had bought

in the states to give to English kids. But we hustled the rest of it to

our tent, through the mud and dumped it on the wood floor.

An hour or so later we found that we could get a meal at a mess hall

and waded through more mud to get there. Baloney sandwiches and coffee,

the standard meal for flight crews! The next morning we had a taste of

powdered eggs and salt bacon with unmixed dry lumps, and the usual cereal

with canned milk. Compared to the sour mess hall guys, the food looked

good. We ate it, there was no other choice.

Ed came back and told us to get ready, we were taking a Gooney bird to

England. We got together all our baggage, and manhandled it to the

flight line. Then we went over to the B-17G we had flown over, to get

the food we had left. It was gone, probably stolen by the transient

aircraft ground crews. So much for oranges for the English kids.

We landed at Eccleshall and had our first taste of the ubiquitous English

"biscuit" mattress, three iron hard rectangles of horse hair covered with

canvas.. It was claimed that these biscuits were used by the British

troops too, but secret documents revealed after the war, show that

Churchill had directed that these things be designed to keep American

crews as tired as possible so that they wouldn't be running in and out

of British towns, disturbing folk, and especially young girls, who needed

rest so that they could perform their war duties in the munitions plants.

Whatever the reason, they were impossible to keep together at night,

so that as you slept, they slid apart until your nether side was

exposed to the cold British night. One guy I know said that he had

tried to nail them together, but that nails would not penetrate them.

At Eccleshall, the crews were split up. The officers went off to one of

those mysterious places that only officers can go. Probably some palace in

London, and we enlisted personnel were sent to a camp up on The Wash, near

King's Lynn. This was another of those bases selected by The Washington D.C.

Site Selection Committee. Coldest spot in England in June or any other time.

The winds would whip in across the Wash, direct from the North pole and

at near gale force. Being as it was so cold we were barracked in squad

tents, issued the biscuits, two blankets and a comforter. The nights were

so cold that most of us wore our flying gear to bed. The latrines were

the other side of nowhere, and it was very coooold!

Last call at night, everyone would high tail it to a huge hedge row, at

the edge of the tent rows, to "hang it out," one last time. One night,

some joker stole a bunch of pepper from the mess hall, liberally laced

the hedge with it, and waited in the dark till there was a good line up.

Then he stood up at the end of the row, and fired several rounds from his

45 pistol, down the row. This shook loose the pepper and it scattered it

all over everyone, resulting in a lot of sneezing, cursing and threats.

The main mission at The Wash was to teach us how to shoot at tow targets

towed by slow aircraft flying down the row of machine guns and turrets

on the firing line. It was known that the Germans often used this highly

effective tactic against the 8th AF formations at high altitude.

We were slightly bored with this after the first day, and also

very cold. So we found that by concentrating our fire power,

perhaps 40 or 50 machine guns on the tow rope, rather than the

target, we could usually cut the rope. The tow planes only

carried one or two targets, and they were probably happy to

get out of there, knowing that most gunners located the target

in their sights by finding the plane, following the rope down,

then firing on the target. At any rate that's what we thought

we were doing, but once in awhile, some slow thinking gunner

would get the procedure wrong and fire at the tow plane! So

the Lysander and Whimpy pilots were understandably anxious to

get the hell out of there at the slightest excuse.

Air shot of B-17G named Skinny. I flew several missions aboard her.

No chin turret as it was lost and rebuilt without one. (1944)

D-Day had come and gone. We were carrying 45 pistols all the time now,

because it was a known fact that the Germans were going to mount a

counter offensive at any moment and the weakest point they could find

was The Wash, defended only by pistol armed American air crews.

Guns played an important role at The Wash. That's where we first

experienced a handful of 45 slugs tossed into a pot belly stove.

That will get your attention. Another favorite trick was to lay a

50 tracer slug atop the stove and get out fast. It would "cook" off

and go whizzing around the tent. One lodged in my oxygen mask one

night. The oxygen mask was in its box, and I had covered it with my

fleece helmet to use as a pillow. My head was on the pillow! We

chased after that guy and would have killed him if we had caught him.

Every once in awhile, someone would get out and shoot a farmer's pig,

butcher it, and share barbecued pork with everyone around his area.

The farmers protested to the base commander, but it went on all the

time. It was generally a dangerous place to be, because a bunch of

undisciplined youngsters, with no supervision will act like hoodlums.

And there was no disciplinary force in the crew tent area. No base

personnel ever penetrated there as far as I know. I don't blame them.

We got on a train and headed for our new base, and it was to be our

permanent base, we were told. We would meet the officers there and

soon start flying against "Fortress Europe." Boy the brass loved

those terms and phrases in that war. Remember the "Soft Underbelly

of Europe?" "The Eighth Never Turned Back?" Huh! Air crews

contributed things like "Big B" for Berlin, padeecalay for Pas de

Calais, and so on. Actually, I never, ever heard a crewman call

Berlin "Big B." The usual reaction I heard was "Oh Shit!" But that

applied to about everything beyond the coast of France.

So we got on the train. About a third of the guys were boozed up and

there was no disciplinary control. What to do? Whip out the 45 pistols

and shoot at cows in the fields we passed. They did it, believe me.

Made me a believer in discipline, and a lot of other guys, too.

Eventually we arrived at Roughham. Left the train at Bury and were

trucked out to the airbase, good old station 468, home of the 94th

Bomb Group (H). We were a miserable lot, as we stood there in front

of a hut that was Squadron Headquarters for the 331st. All our

worldly goods was in two barracks bags, our flying gear, and a

musette bag, and the First Sergeant was assigning us to barracks.

Cummings crew (that's us) was sent off to a quonset hut.

It held four or five crews, at least the enlisted members of

them, including us. We took the empty six cots and looked around.

Nothing, just a lot of disinterested stares from the other

occupants. We each had a bed and a footlocker. 3 biscuits, two

blankets and a comforter, plus a bed sack to stuff the biscuits

into. Heat was two pot bellied stoves, fired by coal or coke.

No one was in charge. We set up and unpacked, and tried to look

as if we knew what we were doing. Finally Pappy got a conversation

going, and broke the ice. We learned that the latrines were a 100

yards or so down the path. Someone told us how to get to the Combat

Crew Mess ... walk was how you got there. We didn't have bikes yet.

We were dying to asked some of these grizzled veterans about flying

but didn't have the guts. So we just listened to the normal barracks

BS and waited. When they started leaving we followed and found the

mess hall. Typical food in a combat crew mess. Supposed to be

non-gassy so that flyers wouldn't bloat up at altitude. Cabbage,

chipped beef, gravy, bread and potatoes. Non-gassy? Oh well.

We quickly found out that the barracks was the same as at The Wash. No

one was in charge. The same kind of jokers tossing 45 slugs in the stove,

waving of pistols, etc. It was impossible to sleep at night because of

the constant card games and the cursing, the fights, and the general

ruckus caused by 20 or so young men flying against a tough enemy.

Air Shot of contrails of 94th BG on mission. (1944)

After we began flying, practice at first, then later on the real thing,

we got to know that we'd be whistled up at 2:00 AM or so for a mission.

The CQ would come storming through, blowing his whistle and calling out,

"Cummings Crew," or some other crew if we weren't going. We quickly

realized that no sleep wasn't going to cut it. If we got an hour or so

it was unusual. So we began to look around for an alternative.

There was a tent area with several squad tents occupied by

other crews. They seemed happy. So Herb and Pappy started

trying to make a deal. I think they finally bribed someone

in the Orderly Room and we had a tent. Canvas, a stove, and

a dirt floor. But by this time, in July of 1944, we had begun

to fly and knew a few people here and there. The ground crew

of our airplane helped us get a bunch of old bomb cases and

we managed to scrounge a hammer and a saw. With this we tore

apart the bomb crates and built a wood floor with side walls

up about four feet on the inside of the tent.

I found a pile of bricks, and liberated a few at a time until we had

enough to make a fireproof platform to set the stove on. We found a

door and some hinges somewhere and we were in business. Snug as bugs

in a rug! Warm, safe, and it was quiet at night. We had a light we

could turn off when we wanted to and began to get some sleep.

*BICYCLES*

We had to get bicycles, and managed to buy one each. This made it

much easier to get around. To the mess hall, to the NCO Club, and

to the PX. Actually, those were about the only places we went on base.

Trucks hauled us to the flight line and to briefings and all that.

Getting to the club was much easier with a bike. Getting back home was

much more difficult. Lots of ditches and no lights made travel treacherous.

A general unsteadiness, probably from extreme stress, or maybe it was that

watery beer we got by the pitcher? Who knows? No one on our crew ever

broke a limb, but we pulled ourselves out of ditches more than once!

Bicycles were our main transportation in England. Of course no one had

a private car, not even the officers. We all managed to buy or scrounge

ancient 2 wheelers from men who were returning to the Z.I. (Zone of

Interior), or Land of the Big PX. They were all old and worn, but they were

enough to get around the base and sometimes into Roughham, the nearest pub.

That made for a dangerous time! Riding into the pub was not too

bad. Plenty of light as wartime Britain was on double summer time

and it was nearly light enough to read a newspaper at 10:00 PM.

However, a few rounds of beer, a few choruses of Roll Me Over

and the ride home became dangerous. There were absolutely no lights

in blacked out England and the effects of the beers put a lot of

fellows in the ditches that lined most roads. Many friends ended

up in the water of a ditch, and many an arm or hand was broken!

We quickly learned that there was an etiquette to these country

pubs. First of all, whiskey and gin were scarce and the locals

resented a crowd of G.I.s pushing in and drinking the pub out

of booze in a quarter of an hour! We were wealthy according to

their standards and this was a resentment too.

We on Cummings crew quickly adapted to the situation and confined

ourselves to the rather watery beer that was wartime Britain's lot.

We would buy a beer, and maybe a round for the regulars, then Bob

would sit down at the ever present piano and begin to play jazz or

whatever popular song was on top at the moment. Bob had been a

professional band pianist and was a very talented guy!

He'd play and we'd start to sing, then the regulars would start

to sing. Once that got going, they'd begin buying beers. Soon

the piano was covered with pints and we were well underway.

The British liked the old favorites like, Roll Out The barrel,

current hits like White Cliffs of Dover, and Bob taught them a

bunch of old jazz tunes, Barrel House Bessie, etc. We'd be roaring

away, everyone having a good old singfest, when the stentorian voice

of the publican would roar out: "Time, Gentleman!" And just like that it

was over, pints were hurriedly downed, and off we'd be into the night.

Then came that dangerous trek home. If we'd had a bit too much Pappy

would warn us all and it was a push-the-bikes night. We always made

it safely and we didn't really go out very often, just when we felt

sure we wouldn't be called out for a mission in the morning.

On a particularly rough mission to ___________, our plane (Shady Lady)

was shot up pretty badly. We'd been hit very hard by concentrated Flak

going in to the target, over the target, and coming out. The plane lost

and engine, and we left formation as we couldn't keep up. As we slowly

descended, prop feathered, we pushed on back to England on our own.

We soon had another engine threatening to quit. We dumped everything

overboard to get the weight down. Heavy flying gear, what ammunition

we felt we could spare, tools and so on. Jim fought to keep the plane

in the air and we crossed the channel and saw the English shoreline

ahead. Just about that time the second engine gave up and we were in

deep trouble! 2 engines on a badly shot up air frame are not enough to

maintain altitude and we had already gradually sunk to about 2,000 feet.

There was a giant airfield at Manston, in southern England. especially

engineered for crews just like us. It had extra long and broad runways

to accommodate shot up airplanes. Along side the main runway was a huge

plowed field for planes that couldn't get their landing gear down, or

who feared to try to land on a hard runway. It was like a heaven for

crews like us! Jim managed to get Shady Lady lined up for an approach

and we slowly staggered toward safety. Just before touchdown, the third

engine cut out, was quickly feathered and Bang! We slammed down on the

runway. Jim took Shady Lady down the runway, quickly found the

hydraulics were shot up and there were no brakes. As we slowed he

turned off the runway and spun in on the plowed dirt.

We spun around, lurching and a huge cloud of dirt spewed

into the air. The crew was tossed around quite a bit,

but we managed to get through it without a scratch.

Ground shot of B-17, Shady Lady on ground (Shot Down, 1944) in

Germany. I thought this was "my" Shady Lady but it turns out it

was another group's. "Shady Lady" was a popular song of the era

and they ended up as names of lots of ships in all groups. (1944)

We were quickly picked up by a truck and returned to operations

building. Here the officers related the problems and we were asked

if we had any injuries we hadn't reported? Nope and off we went to

an RAF Sergeants Mess, where we were bunked down. Later we went to

the dining hall for a meal which was strange to us. Very greasy

mutton, cabbage, and boiled potatoes. Not very appetizing. And we

complained about the food we were fed back at our own base!

In the morning we were awakened with a mug of very strong tea with

milk in it and had a bite to eat at the dining hall again. A bite

was about what it was. They served cold toast, smoked haddock, and

the inevitable tea. Strange to us at the time, and we didn't eat much.

A few hours later a USAAF B-24 bomber came in to pick us up along

with a couple of other crews in the same plight. We looked the

"24" over carefully, being suspicious of an airplane we considered

2nd rate, compared to our B-17 Flying Fortresses. It looked okay

and anyhow, we had no choice. So off we flew in to the wild blue

(gray) yonder. A few minutes later we landed at a base where the

first crew got off. The B-24 stopped in a low tail position and

the rear door couldn't be opened so a crewman told another gunner

and me to jump out the front and go around and the tail up.

We did so, skeptically, and put our backs to it. Behold! It lifted

up and the doors opened and the crew that was at its home base

jumped out, the door was closed, the engines revved up, and we taxied

out and took off for the Roughham Airfield. We landed there and went

through the same procedure, a truck picked us up and we went on to

operations for a debriefing and then back to the squadron area.

We found that we had been presumed lost, as the last that had

been seen of us was the sad sight of our bomber, trailing smoke

and shot up, leaving formation and headed down. Apparently the

94th had not had the word that we were safe in Manston.

We got to our tent and found it had been ransacked. All our personal

belongings had been packed and stored for shipment to our next of kin.

Of course the scavengers had been there and stolen most everything except

uniforms. Books, pens, writing paper, a wind up phonograph, my collection

of Dinah Shore records, and more had all disappeared! Our clothing we got

back from the orderly room. I found my stationary box complete with my

little private diary mission notebook, and a partially written letter to

my parents in the possession of a gunner in a Quonset hut. He denied it was

mine but gave it up after the letter to my folks was found in it. A brief

and furious fight erupted but I was hauled off before I could kill the thief.

This was a common occurrence, a missing crew's personal belongings were

often stolen by erstwhile friends. We got most ours back except for the

records and the phonograph. The whole crew got their bicycles back except

for me. The First Sergeant had it and denied that it was mine and there

wasn't much I could do about it. I could probably had whipped him but I would

have ended up in Lichfield, the ill-famed G.I. prison. So I just let in lie.

Merseberg, Germany. I flew 4 or 5 missions there, the toughest

target in Germany. The Intell Briefer said "There are 750

heavy AA guns there (88mm and up) but don't worry, only 500

of them can bear on you at once!!!!" (1944)

When the 94th had it's three day stand-down for the 200th anniversary

mission, we really began to swing. Dinah Shore, The Glenn Miller band,

The Phyllis Dixie girls from London's Windmill Theater, and a host of

delightful girls from the local area to dance the night away.... What

a time. We saw the Band, we saw Dinah, we saw the Phyllis Dixie Girls,

danced about one dance, then Pappy and I stole a keg of beer from the

NCO club. This created a slight problem. How do you get a keg of beer

home without getting caught, and how do you move it? We knew it was too

far to roll, so, in a slightly (!) tipsy state, we proceed to load it on

a bike and started up the road in the dark, Pappy holding the bike erect

and me pushing. We only dropped it a couple of times and only once did

it fall in a ditch. But in the end we managed to get it back to the tent.

This was a coup, if ever there was one. We stayed in the tent

with that beer for the rest of the three day stand down. Other

crews, neighbors knew we had it, but we wouldn't let them in.

We'd send one man out to scrounge food, and that's the way we

celebrated the 200 mission anniversary of the 94th!

There was a notice on the Squadron bulletin board to the effect

that all ladies must be off the base within 24 hours of the close

of the three day stand down. It was purportedly signed by the

Squadron CO. Whether it was legitimate, I never found out. Didn't

concern us anyhow. We had a keg of beer to make disappear!

More contrails. (1944)

Food was a constant concern. The best a mess can do is try. They didn't

often have the greatest ingredients. Canned rations, lumps of powder in

the scrambled eggs, and soggy pancakes can sure put you off, and the

bread was terrible. We used to steal food when we could. One afternoon

we "found" a sack of fresh potatoes and had the crew officers up for a

snack at the tent. The pilot, Jim Cummings, the best natured man in the

world, as well as the best pilot in the same, sat there peeling potatoes.

Joe Toeniskoetter, the Navigator, and Fred Masci, the Bombardier,

washed them. Pappy Painter did the frying in oil, and we all did the eating.

We often broke into a hut in a warehouse area where emergency

K and C rations were kept. Pappy was adept at cooking these,

adding a few ingredients, and serving up gourmet meals out

of rations that troops throughout the army had learned to

hate! And all on our little pot bellied stove.

That little stove was designed to burn coal or coke, but along

with a lot of other crewmen, we adapted it to be an oil burner. We

scrounged a 55 gallon drum, ran a tube from it to the stove, with

a control valve to control flow, and dripped crankcase oil onto

a fire. It really kept us warm and without the fuss and mess of

coke/coal, which had to be hauled from the squadron orderly room area.

Other crews did this too, and once in a while you'd hear a loud

WHOOMF! Someone had gotten crankcase oil contaminated with 100

octane gasoline, and it blew! Startle the heck out of the guys

in the tent or hut, to say the least.

We used 100 octane for our own patented dry cleaning. Put the wool

uniforms in a can of it and rinse it around. It was odoriferous to

say the least. The most humiliating moment of my life came as a

result of the 100 octane dry cleaning method. A high school friend

and I were checking into a Red Cross Hotel in Oxford one afternoon,

and this very haughty woman, Lady Something-or-other, sniffed loudly

and said, "Whatever is this ex-trord-nry odor of cleansing?" As only

a Brit can be snooty! Of course it was me. I felt like dropping

into the nearest deep hole! Oh, well, what it was, was stinking!

For laundry, we'd build a fire outside and boil a can of water, with

dissolved yellow GI soap in it. Then we'd swish our clothing around

in that, and they'd be white, white clean! Better than the famous Rinso

White! One gunner had a surprise. He tried boiling 100 octane to "make

it clean faster!" It blew and he singed half the fellows in his tent!

More contrails, 94th BG. (1944)

One problem I always had in the Army, was showers. The 331st had

no hot water when I got there. The First Shirt took up a collection

and a bloke put in a boiler to heat water. The first day was great.

The first night, it blew up! End of hot water.

I always used passes in the Army to get a hotel and a tub, and

spend most of the time reading and soaking. Plus getting caught

up on my rest. Yes, it's true, I was 18 and thought that was a

great way to spend a leave. Imagine my disappointment on my first

48 hour pass to London. Went down the hotel hall to the bathroom,

and there was this huge bathtub. Great, just what I wanted. Had

a line painted around the inside about 2 inches from the bottom.

A sign explained that we were only allowed to fill the tub to

the line, so as to conserve water for the war effort!

One more thing about station 468. There were constant rumors that

summer of 1944 that he war would end soon and we'd be sent here

or there. That's what they were, rumors. I and a gunner from another

crew sneaked into a storage area one evening and painted a bunch

of Chinese characters on several cases. We'd gotten the writing

off a Chinese menu or something. Then we started telling people

about these packing cases with the Chinese writing on them. The

rumors began to fly fast and furious. China was our next destination!

Was very cold and got tired of seeing

all this every day - Merseberg (1944)

I flew combat exactly 2 months 15 days, and finished on September

23 with a little trip to Kassel. It was with no regrets we left our

tent ten days later, and the crew was on it's way to Bamber Bridge

by train. I've never known how I could spend WW II in the Army

Air Force, and never travel by plane. Always, except for crossing

the Atlantic, it was either train or the back end of a 6X6 truck.

I have never been sure where Bamber Bridge is, and don't really

care. We arrived there, and were greeted by a T-5 who made a

little speech. "You men," he said, " have done your bit, but

while you're here you'll be working for us!" And he wasn't

kidding. We were all SSGTs and TSGTs. We built fires in the

early morning for the offices so the base cadre wouldn't have

to come into a cold room! We pulled KP, picked up trash, made

garbage runs, and were generally treated like a bunch of

prisoners or basics. It was a trying time for our young egos.

The barracks were old cinder block RAF barracks with

very small rooms and bays. The usual mattress biscuits.

The first day I walked into the dayroom, I saw German

Lugers, P-38s, NAZI daggers, helmets just lying around.

I asked who they belonged to. A gunner told me no one!

But he said not to get excited, that we weren't allowed

to take anything back to the states with us. They had been

discarded by former transients. The base cadre had their

pick. We found out what they were talking about the day

we left. We had to take all our personal luggage to outdoor

inspection stations equipped with long wood tables. Here

our bags were searched and anything prohibited taken from

us. They took two chunks of FLAK from my pocket, and several

British civilian aviation magazines! They were returned

to me several years after the war, via registered mail. But

nothing surprised us, nothing daunted us. We were going home!

So off to Glasgow by train to get aboard the Queen Mary. We had

to stand in line for several hours while we waited for the military

processing teams to get up from their naps, and a young Scot came

by. I asked him if he could get me six bottles of beer. I wanted

to take it home for my father. He took my money and left and came

back with the beer, which I concealed in my army greatcoat.

We finally filed aboard the ship and proceeded down to the bottom

hold where we deposited out baggage, then back up to pre-assigned

staterooms. About 10 or 12 to a room. We had been given a piece

of canvas and a length of rope and told to make up our bunks,

which were three high racks of iron pipe. None of us ever figured

how to make up a bed, navy style, The guy above was sagging into

my lap. But before we could get settled, the word was passed that

there was another personal inspection team coming round. Knowing

they would confiscate my dad's beer, I quickly drank the six

beers. That inspection went very pleasantly for me!

An hour later, a crew of blokes came around and unscrewed

the toilet seats from all the bathrooms...each room had

it's own bath. But we weren't allowed to sit on a seat!

There were only a few thousand people on the ship, for

this was only October, 1944. I was assigned as an MP on

ship and also to a 40mm Bofors quad mount AA gun tub.

What a thrill firing that in practice. The MP duty was

easy. There were a hundred or so civilian VIPs aboard.

We were to prevent them from being contaminated by

exposure to we GIs. One great star, a woman called

Bea Lilly, screamed terribly at one poor guy who

happened to spot her and dared to ask for an

autograph. She wanted me to "arrest" him!

The food was British and pretty much up to their usual wartime

standards. It was new for us to be served family style, with

platters of mutton and potatoes passed around. Many men

couldn't stomach it and went out to pray to the toilet.

Of course many men got sea sick while we were still in port.

After returning from overseas at age 19. (Nov 1944)

It was on the Queen Mary that I first saw movies from the back

of the screen. The transparent screen was stretched across one

of the covered decks and my place was behind the screen. I

still believe everyone in "Alexander Graham Bell is left handed!

We arrived in New York in early November. The Red Cross met us

at the bottom of the gangway,and passed out fresh milk, the first

most of us had seen in a long time. Donuts, too! Very welcome.

We were sent by ferry boat to Camp Shanks for reassignment. Until very

recently I swore that Camp Shanks was in New Jersey. Had many arguments

over it in the last 45 years. Found out it is in New York! I was on the

site a year or so ago. If I was wrong about this, a memory I was

absolutely certain of, it makes me wonder what else I'm so wrong about!

At Camp Shanks we were treated like royalty. No inspections, didn't even

have to make our beds, but we all did. We were served four meals a day,

and could have steak for each meal, if we desired. Yugoslav (can that be

right?) prisoners served meals, dished up the goodies, bussed the tables.

We had several days to do what we wanted and most of us were in

New York City every day. Met some grand people, and some nice

girls. I remember a cab driver driving me all over Manhattan

looking for my date. I had forgotten the name of the place I

was to meet her. We found it, and he wouldn't take a nickel!

This was November, 1944, and combat returnees with ribbons and

wings on their chests were fairly rare. Bartenders were always

serving drinks that someone had ordered for us. A heady

experience for a young guy, already a grizzled veteran at 19,

trying desperately to think of a war story...."There I was at

40,000 feet flat on my back, when Boom! went the copilot....yes

Sir, I'll have another drink, and I thank you Sir and Madam!"

Well all good things must come to an end and we were loaded on another

troop train to head cross country. The idea was that the train would

stop in cities along the way and disembark the troops that were going

to whatever area we were in. Let off a few crews here and a few there.

You may remember that Chicago had two separate railroad stations and

normally you got off at one, and made your way to the other to continue

on west. With us, they spent the night shunting around Chicago, moving

our cars over to the other station. We'd move for ten minutes and sit

for two hours. Finally we decided that one of us should go into the

nearest liquor store and buy about 20 bottles of various types of booze.

I was selected to go be the buyer, jumped train, and headed for town,

scared to death that I'd be caught. I had a wad of money in my pocket

and finally found a liquor store. Bought a case of assorted bottles

and headed back to the train. The case got heavier and heavier and I was

in a half trot. When I got to the rail yard, the train was gone. A train

crew man told me that it had gone over there, pointing off into the night.

I began to run and eventually caught up to the train, to the welcoming

shouts of my friends. I was dead tired and soaked in a sweat. My uniform

was ripped, and I didn't care if I ever had a drink. Ordeal by train!

Eventually the train arrived in Utah, and we all watched in wonder

listening for sirens and gunfire from the station. Never heard a thing.

You see, we had watched a crew get off wearing their A-2 leather jackets.

On their back each had the usual painted B-17 and the name of the aircraft.

Their's happened to be called "The Frig 'Em Young!" Never heard a sound.

From Salt Lake City, we proceeded to Monterey, California. At

Oakland, the train had to be put on a ferry boat to get across

to San Francisco. I called my Dad who met me at the station.

He took me home for a real mom-cooked meal. Then back to San

Francisco where I rejoined the train. On to Monterey and there

they gave us a 21 day "delay enroute." So I headed back home

and spent a great 3 weeks showing the uniform, and waiting for

someone to ask me about the war. It was California, and I was

only 19 so I couldn't go in a bar. But no one would talk about

the war. I found out that they had all read magazine articles

that told them that returning GIs didn't want to talk about

the war. What a crock that was! My dad finally asked me if

the "food was as bad as it was in the Great War?" I told him

I really couldn't compare but I figured it might be equally

as bad. This was all I got from my old man. He was the guy

who gave me the two greatest pieces of advice a dad could give

his son leaving for war. The first was find the oldest guy in

the outfit and do what he does. The second was better! "Don't

ever shoot craps on a blanket!" What else does a man need?

On leaving home I proceeded to Santa Anita AAF (the race track!), in

southern California. This was an old aviation cadet base converted to

a reception center for returning overseas veterans. The small mess halls

had double rations to feed us. The food was magnificent with a choice of

main courses and an unlimited supply of veggies, fruits, milk and ice

cream! If Washington had ever heard what they were doing for GI's heads

would have rolled all the way from California back to Washington.

Part of the mission at Santa Anita was to determine if we had any

psychological problems. If you said you had nightmares, or didn't

have nightmares, if you couldn't sleep, or complained of sleeping

all the time, and so on, whatever you said you could stay in this

paradise for another week. Some guys played this game for weeks.

I went to the Hollywood Canteen and saw big stars serving ice cream

or talking to kids like me. I experienced the surprise of waiting

to cross at stop light and have people offer me a ride. "Sorry, and

thanks, but I'm just trying to cross the street!" I had a blind date

with the most beautiful girl I've ever seen, and here I was a kid out

of high school, but wearing the magic ribbons and wings!

Finally I couldn't stand it any more. Life was too good! I decided

to go home for a few days and went AWOL to do it. After a few days

at home, I began to worry that I'd get in big trouble, and in my

imagination, there was an M.P. waiting around every corner. I hopped

a commercial DC-3 back to Los Angeles, dodging real MPs at Burbank

Airport, and made my way back to Santa Anita. I slipped in the gate

and walked over to the barracks. The first sergeant hailed me and

yelled at me. "Where've you been, I've been looking for you all

morning!" My legs sagged, but I quickly found that I was safe. I had

signed up for combat crew on B-29s, and he had my orders for Las Vegas

AAF. I argued that Vegas was still B-17s but he told me I was wrong.

Arriving at Las Vegas I found that I was right and I was back

on B-17s, but that wasn't bad. Problem was I had been through

gunnery school less than a year ago and the instructors were

wary of the few combat returnees that were showing up. So they

made me a flying instructor for the length of my schooling.

Here, barracks were not a problem. I was a staff Sergeant and

they gave me a room in the cadre barracks. Pretty neat. I

rather enjoyed this period of school. But all things come to

an end, and I was shipped to Lincoln AAF for crew assignment

just in time to find the blizzard season. We were in 20X50

huts with latrines just over the snow banks. I was back to

basics again. Pot belly, coal fired stoves and all. One good

break there. I was made a detail sergeant and the first day

in front of the Gis falling out for dirty details I found my

basic training D.I. standing in front of me. He shoveled

enough coal in the next few days to make him remember his

treatment of us poor young men he hassled at Shepherd AFB.

Boy oh boy, vengeance was mine!

Ultimately I was assigned to a crew at Lincoln and we entrained

on the Rapid Canyon Limited for Rapid City AAF, SD. Still snowing

and it seemed to the entire two months we were in crew training.

In fact it was snowing when we left in May.

RCAAF was equipped with the standard two story barracks, with over

100 men in each. Since I was made Barracks Chief, because of my rank,

I quickly became acquainted with its workings. Being a 19 year old

staff wasn't all that great. I had no idea of how to supervise 100

men. No training or experience. I was a gunner. Big deal, so was

everyone else, though they were mostly PFCs and corporals, with a

few busted NCOs scattered throughout. My method was that if they

wouldn't do what I said we'd fight it out. Sometimes I won, sometimes

I lost, but I never gave up. What a lousy NCO I was! I hadn't a clue!

There was often a problem GI in a barracks. Once in awhile there'd be

a fellow who wouldn't bath. Almost always they were guys who would

never take off their clothes, sleep in them, atop their beds, and just

smooth the blankets down when they left. They usually became quite ripe

after awhile, and the men around them would complain. We had one here.

When I was told of the problem, I went over to his bed, and the aroma

was "channel 10," the ripest of ripe!. So I told the guys what to do

and when he returned to the barracks, a bunch of them grabbed him,

stripped him, and took him to the shower room, where he was scrubbed

down with a floor brush and harsh GI soap. It must have been quite

painful and he put up a heckuva struggle. But we no longer had a

problem. Saw the same treatment several times in my enlisted career.

Heating was provided by a coal fired boiler in the barracks. We had a

24 hour detail to keep the boiler going. If the fire went out, so did

our heat and hot water. And it was cold in South Dakota. If the fire

was built up too high, it would burn the grate out. Then we had to

scrounge up a new one, wait for the boiler to cool down, and replace

the burned out one. And one or the other seemed always to happen in

the middle of the night. If I was particularly mad, I'd just punch

out the offender. If he could do it, he'd whip me.

Remember there were no officers around one of these squadrons. The only

cadre I dealt with was the old timer First Sergeant and the Supply

Sergeant. That's the way they dealt with problem GIs. What a way for

the modern manager. Later I saw this old line method used as late as

the 1950s. A First Sergeant would take a recalcitrant out behind a

barracks and beat the bejesus out of him, rather than court martial

the kid. Crude but effective. But I just didn't know any better!

At any rate, between the barracks and the flying I was a busy man. I

didn't like the crew much and could usually beg off flying when I wanted

to. I'd go into town and get a hotel room and soak in the bath. Ah, luxury.

The second most embarrassing incident of my career occurred At Rapid

City. President Roosevelt had died, early in April, 1945, and we were

to fall out for a memorial parade. I formed up my squadron. Not really

a squadron, but it was too big for a flight. Got all set up and gave

the command, "Dress, Right, Dress." I walked the ranks looking to see