The French Tunnel

In 1941, nine French prisoners began what was to become the most impressive tunnel dug in the castle throughout the war. Having decided that the exit should emerge in the steep drop leading down to the recreation ground, outside the eastern walls of the castle, they began to assess all the possible locations for its entrance. The problem was solved by the experiences of Lts. Cazaumayo and Paille, who had gained access to the clock tower in 1940.

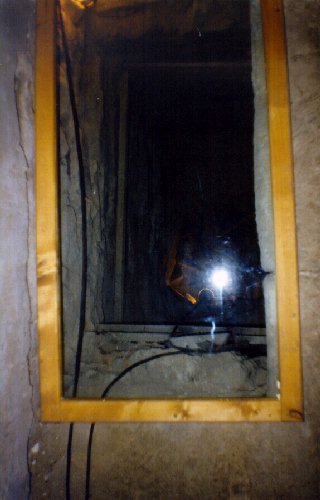

They found that the weights which used to hang down the shaft, and their accompanying chains, had been removed. This left empty cylindrical sleeves which extended from the clock to the cellars below. After the escapades of Cazaumayo and Paille, the doors (one on each floor) which provided access to the tower had been bricked up in order to prevent further escape attempts. However, by sealing up the tower the Germans had inadvertently provided a secure location where work could go on indefinitely. The French this time gained access to the tower from the attics at the top, and having descended 35m, entered the cellars in which they could begin a horizontal shaft. Work on the tunnel began in June 1941, and continued for a further eight months.

They began to dig towards the chapel, hoping that they would find a crypt. However, after 4m in this direction with no signs of a crypt, they began to dig upwards towards the floor of the chapel.

From here the tunnel continued underneath the wooden floor of the chapel for a distance of 13.5m. For this to be achieved, seven heavy oak timbers in the floor, measuring 40cm square, had to be cut through. Home-made saws, assembled out of German table knives, were employed for this task. With this completed, the tunnel dropped vertically from the far corner of the chapel a further 5.2m.

From here, the tunnel proceeded out towards the proposed exit, with two further descents, separated by horizontal shafts in the tough stone foundations of the castle. The tunnel now ran a horizontal distance of 44m, reaching a final depth of 8.6m below the ground.

The tunnel itself was a major engineering achievement. It was fully installed with electric lighting along its whole length. The prisoners had wired their circuits to the chapelís electricity supply. Not only did this allow the tunnellers to see what they were doing, it could also be used as a system with which to signal to them the arrival of any sentries nearby. The entrance to the tunnel was concealed by a hinged stone door which left little trace of any hole. Debris was transported from the working face by means of several sacks moving on sleds, and then hoisted up the clock tower and disposed of in the castleís attics.

So, tunnelling continued well into 1942. By this time, the Germans knew that the French were digging somewhere in the castle. The security forces were tormented by the sheer arrogance of the French who, working in the dead of night, were aware that the reverberating noise of their tunnelling could be heard by the Germans, but their confidence in its undetectable entrance was total.

However, on 15th January the Germans eventually searched the clock tower which they had sealed off over one year ago. Noises were heard from down below, and after lowering a small boy down the shaft, three French prisoners were found. After searching the cellar thoroughly, the entrance to the tunnel was eventually discovered.

Upon its discovery, the tunnel was only 30 feet short of completion. The earth at this point was soft and easy to work. The Germans had discovered the tunnel just in time.

The French were convinced that they had been betrayed by one of their own countrymen who had been transferred to another camp at Elsterhorst, but this is denied by Hauptmann Eggers. The final blow for the French was a demand by the German authorities for money to repair the damage caused to the clock tower, attics, and the floor of the chapel. The work was estimated at a cost of 12000 Reichsmarks (nearly £1000).