SEARCH FOR A HERO

SEARCH FOR A HERO

By Bill Marvel / The Dallas Morning News

08/02/99

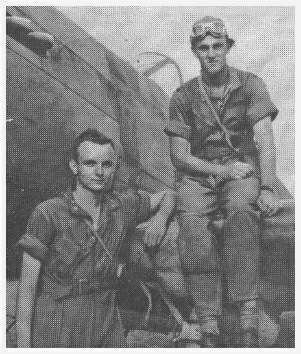

WWII flier finally finds the pilot who saved his life They never knew who he was.  All they knew is that they were in trouble. Their bomber had lost an engine All they knew is that they were in trouble. Their bomber had lost an engineand they were now flying alone, way below the rest of their formation, a fat, juicy morsel for any German fighter that came along. Then an American P-51 appeared off their wing tip, a guardian angel to see them safely home. They had just started to relax a bit when the German fighter did appear. It hurtled down from somewhere above and behind them, faster than anything they had ever seen before. It blasted the P-51 out of the sky, then rolled toward Earth and disappeared. If that P-51 had not been there to take the attack . . . And they never knew who he was. Four months ago, Everett Jones saw a model airplane magazine on a newsstand. The shape on the cover caught his eye. Sleek and bat-winged, it was the same shape he and his crew had glimpsed in that electric moment over Germany 55 years ago - an Me 163 Komet, the rocket-powered German fighter. But Mr. Jones was not thinking about the German plane. He was thinking about the fate of the American pilot. "I had never really forgotten," Mr. Jones says. "But when I saw that magazine with that cover on it, that really lit my fuse. I thought, there just has to be a way to trace that, to find out who that P-51 pilot was." A few days later, Mr. Jones placed an ad in Air Force magazine: "Seeking information on a P-51 pilot shot down in the Gelsenkirchen, Germany, area Nov. 1, 1944." The first letters arrived within weeks. A thick sheaf of correspondence and documents began to accumulate. Nobody had the whole story, but each had a piece of the puzzle. Mr. Jones knew the American fighter pilot who sacrificed his life that day was a hero, but he didn't know who he was. The others knew who he was, but they didn't know he was a hero. It took all of them to put the story together. "You'd have to know my brother," says Tom Alison. Tom is a retired mortgage banker in St. Clair, Mich. On Nov. 1, 1944, he was in the U.S. Navy. His older brother, Denis Alison - called "Spike" - (at left in photo above) was a second lieutenant, flying a P-51 with the 20th Fighter Group out of England. The two brothers had grown up making model planes. They had taken flying lessons and soloed. Denis soloed first, Tom says. "My brother was a really independent guy. He was already 6 feet tall and 190 pounds when he was 13 years old. He normally got his way. Personality-wise, if he wanted to do something, he did it." When the Alisons got word their son was missing in action over Germany, Tom says, the family was devastated. "With any death like that, it just kind of bugs you. When somebody just disappears - I can't explain it, but you just instinctively try to find out what happened. As far as the family's involved, it's a helluva way to have to lose somebody." About 11 years ago, Tom learned a little more about his brother's death. But only a little, and that almost by accident. One evening, he received a call from a gentleman with a rich Virginia accent who identified himself as James Herbert, his brother's wing commander in World War II. "I damn near fell out of the chair," Tom says. "He said he had a letter from the Netherlands, from someone who wanted my brother's most recent address. That dropped a bomb on me, because when people ask for an address, the implication is that the person with the address is alive. And the best we knew was that Denis was missing in action, dead and everything else." Throughout the Netherlands, Tom learned, small groups have dedicated themselves to investigating plane crashes that occurred during the second World War. Members of one such group had become interested in a P-51 that had crashed outside their village on Nov. 1, 1944. "My brother's P-51 was the only one downed on that date, according to records," Tom says. "That's why James Herbert contacted me." As it turned out, there was a mistake: wrong day, wrong plane. But Tom and a member of the Dutch group, Henk Jensen, started writing to each other regularly. Later on, that would come in handy. In the meantime, James Herbert suggested Tom join the 20th Fighter Group Association, a veterans' organization that includes relatives of deceased pilots. This opened new avenues of information, because Capt. James Herbert remembered Lt. Denis Alison well. Mr. Herbert lives in Delaplane, Va. At age 81, he still flies occasionally, and he still holds a commercial pilot's license. On Nov. 1, 1944, the 20th Fighter Group was escorting B-17s over Germany. There were three squadrons, each with four or five flights. Each flight consisted of four planes. Capt. Herbert was in charge of one of those flights. Think of a flight of fighter planes as a hand extended, he says, fingers together with the thumb tucked under. The middle finger would be the Capt. Herbert's P-51, flying in the lead. "The little finger, number four, is Tail-end Charlie." Denis Alison was flying number four that day. "Unfortunately, Denis always lagged back," Capt. Herbert says. "I had talked to him a number of times about trying to keep up. I took him to the blackboard and showed him, 'If you fly back there we can't see what's coming up on you and protect you.' " But Denis Alison, as his brother points out, was an independent man. It would not be unlike Spike, if things were slow, to go looking for action on his own. That day, Capt. Herbert recalls, there were German jet fighters about, Me 262s that were considerably faster than the P-51s and very dangerous. "Somebody came on the radio and said that a Me 262 was trying to sneak up on a Mustang. I kicked my plane around, and I didn't see any jet trying to sneak up behind us. Ten to 15 seconds later, this 262 came right underneath my left wing. I could have spit in his cockpit." Calling for his flight to follow, Capt. Herbert dropped the nose of his Mustang and gave chase. For a time, it appeared the jet had outrun them. Then he turned. "My number three man and another cut a circle inside us and shot his engine out at 16,000 feet." Engagement ended, Capt. Herbert called for his flight to form up. "And Alison never showed up," he says. "I just assumed that jet had gotten Alison." So it appeared on the official Missing Air Crew Report. For 55 years, it was assumed that Lt. Denis Alison had been lagging behind his flight and had fallen prey to a German Me 262 jet fighter. Steve Blake, a post office mail carrier and amateur aviation historian in California, spends his leisure time researching air-to-air combat during World War II. Everett Jones' ad in Air Force magazine caught his interest. Several years ago, he and another historian had looked into an incident involving a P-51 on that date for a book they were writing on encounters between American fighters and German jets. The United States had no operational jet planes during the war. The other historian had died and the book project was shelved. Mr. Blake dug into his files and found copies of the reports and photos of the pilot and mailed them to Mr. Jones. The pieces seemed to fit. Only one P-51 had been shot down that November day; 2nd Lt. Denis Alison had been the pilot. His hometown was listed as Birmingham, Mich. The burgermeister of Wiefer-Lieftucht had reported to German authorities the burned wreckage of an American P-51 outside the village of Legden. Lt. Alison's body had been identified from his dog tags. With German thoroughness, the local police chief noted the contents of the pilot's pockets: eight coins. The body was buried the following day in the town cemetery, plot number three. Now, Everett Jones had a name and photos to work with. He sent a letter to the Birmingham Chamber of Commerce asking for help: "I am on a dedicated challenge to locate the next of kin for a deceased 2nd Lt. Denis J. Alison," he wrote. "I have some information which, I believe, would be of interest to anyone in the immediate family of Lt. Alison." Mr. Jones also mailed an account of the P-51 incident to Steve Blake. He was the pilot, flying lead B-24 with the 466th Bomb Group, Mr. Jones says. They had bombed the synthetic fuel refineries at Gelsenkirchen and had turned back to England when trouble developed in one of his engines. He had shut the engine down and dropped to a lower altitude hoping to restart it once they got out over the English Channel. "There was an unwritten law," he says, "you did not leave your formation." B-24s bristled with defensive armament and there was safety in numbers. Now, 4,000 feet below the rest of the pack, they were alone. "I alerted my crew to watch for anything moving," Mr. Jones says. For 30 minutes they flew on, eyes anxiously scanning the sky. "The P-51 just suddenly appeared up off our right wing," Mr. Jones says. Nobody knew where he had come from. Their own escorts, P-47 fighters, were apparently busy elsewhere. It was not uncommon for a panicky gunner to shoot at a friendly fighter, and the P-51 stayed his distance. But he continued to fly alongside. "We felt better that he was there." Then he was gone. "It was almost instantaneous," Mr. Jones says. Something knifed down through the air, blasted the P-51, turned, dived and disappeared into the clouds. "It was like a flash. We had never seen a man-made object travel so fast. "The P-51 went into all sorts of gyrations and tumbled out of the sky. I don't think Alison knew what hit him." Afterward, back at the base, they described what they had seen. "Oh, yes," the debriefing officer said. The rocket plane. "We know they have those." Something about that bothers Steve Blake, the historian. He says there is no record that on Nov. 1, 1944, any German rocket planes were in the air anywhere near Lt. Jones' B-24. There were the jet-powered Me 262s that day, Mr. Blake says. One Me 262 pilot even claimed to have downed a P-51. But the rocket-powered Komet was still highly experimental. "They had a lot of problems and didn't see a lot of action," he says. "It's hard to pin down, hard to gather evidence after 55 years. I still lean to the theory of a Me 262." James Herbert, Denis Alison's wing commander, accepts Mr. Jones' account. "In light of what Everett says, I believe Alison tried to follow us in that dive but was too far behind. He pulled out and discovered that lone bomber and pulled up to try to help. Then, the 163 flew by." One afternoon recently, Knox Bishop, curator at the Frontiers of Flight aviation museum at Love Field, reached into a display case and placed a small model of the Me 163 Komet in Mr. Jones' hands. Mr. Jones cradled the plane almost tenderly. "Oh, yeah," he says. "That's the one." Everett Jones went on to lead 11 more bombing raids over Germany. He's become something of a hero himself, earning the Distinguished Flying Cross, the Air Medal with four Oak Leaf Clusters. After the war, he moved to Dallas and entered the gas and oil business. But the memory of that P-51 and its pilot stayed with him, "plagued him," he says. "We never saw a chute," he says. "That was the reason for believing he wasn't going to survive the crash. "When you're caught up in combat, you really don't take anything personally. "But I have to feel that German pilot wasn't up there for nothing. He was going to take something. I think he took Alison because he knew if he took us, Alison would take him." Komets were fast, but vulnerable to American fighters. "Alison took our place in that drama," says Mr. Jones. Jet or rocket, whatever shot Denis Alison down, it would be just like Spike to risk his life to save others, says Tom Alison. "The big question mark in my mind had been how my brother happened to separate from his squadron in the first place. He must have spotted this bomber flying low. Obviously, it needed an escort. "When bombers got to be alone, they were dead ducks. If he'd seen that happen, he would have done what he did. "I'm not happy he died, obviously. But I am happy that's what happened." Many years later, while he was corresponding with Henk Jensen, Tom mentioned to the Dutchman that his brother had been buried in Legden. Mr. Jensen traveled to Germany to photograph the cemetery and sent him pictures. During the war, townspeople had buried 13 downed flyers, from England, Canada, Australia, Poland and the United States. "After the war," Tom says, "the British came to take their men out of the cemetery. Eventually, the Americans were taken. "But in the process, my brother's body was lost." Tom Alison wrote his congressman. Then he wrote then-President Bush. He got a packet from Washington with his brother's entire file. He was told they even dug up a grave in the British cemetery. The body of Denis Alison has never been found.

|

RETURN TO THE 20TH.FG

(Photograph courtesy of Martin Kösters)

Unless otherwise noted, all content © copyright The Art of Syd Edwards 1998-1999-2000. All rights reserved and reproduction is prohibited.