July 13, 1998

Geocities' Cyberworld Is Vibrant, but Can It Make Money?

By SAUL HANSELL

ick Brown did not set out to be anyone's hero. Simply wanting

to learn a little more about the Internet, he signed on two years

ago with Geocities, a service that gives people free space to

publish their own pages on the World Wide Web.

ick Brown did not set out to be anyone's hero. Simply wanting

to learn a little more about the Internet, he signed on two years

ago with Geocities, a service that gives people free space to

publish their own pages on the World Wide Web.

|

Scott Cohen for The New York Times

|

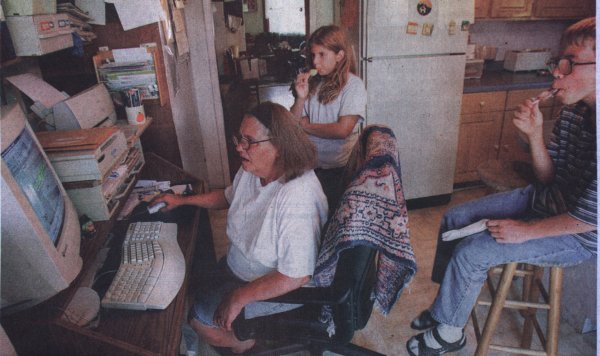

Sherri Kaufmann, who has Web sites in the Picket Fence and Heartland Prairie areas of Geocities, works on them in Gaylord, Minn.

|

Some people use their Geocities sites to show the world their

children, their poetry or their model train collection. Brown built

a tribute to Monty Python, the British comedy troupe.

His Web site started slowly, but Brown, 34, a grocery store

merchandiser who lives in Bridgeport, Conn., kept adding Python

memorabilia, sound clips, scripts and pictures. Soon the site took

on a life of its own, and Geocities began promoting it as one its

"landmark" pages.

By June, when he had a falling-out with the service over a

promotion effort, his site had attracted more than 100,000

visitors.

Brown's experience exemplifies the paradox of Geocities: The

service is attracting an impressive and growing number of members

and visitors, yet as it moves toward a public stock offering, it is

struggling to formulate a credible image as a viable business.

The founder of Geocities, David Bohnett, says that the sheer

scale of the service's operation and popularity would have been

unimaginable when he started experimenting with the Internet in

1994. As of June, more than 2 million members had created personal

Web sites consisting of more than 15 million pages on nearly every

imaginable topic.

|

Many Users, Little Profit

While Geocities is growing in overall customer reach* and revenues, its losses continue to pile up.

|

|

|

Sources: Geocities reports, Media Metrix

|

The New York Times

|

Organized into 40 virtual "neighborhoods," these sites add up to the third-most-visited

domain on the Web, attracting 14 million viewers in April, the most

recent month for which figures are available.

The audience for Geocities has been growing at twice the speed

of the average Web site, according to Media Metrix, which measures

traffic on the Internet.

Now the company, based in Santa Monica, Calif., is going public.

The investment bankers promoting the initial public offering hope

investors will be drawn to the potential of Geocities' vast

audience and to the low overhead of publishing a site created by

millions of volunteers.

They also hope that investors will not be discouraged by

financial statements that suggest only the weakest vital signs of a

going concern.

Of course, as the company begins its road show over the next few

weeks, it will probably talk of many plans to build its audience,

to sell more advertising and to extract fees from at least some

members for certain services.

But it is not clear whether the service can build its business

without alienating its members. For example, it was a promotional

effort known as a watermark that set off the feud with Brown.

The watermark is a translucent image of the Geocities logo that

hovers in the lower right hand corner of the pages of its members,

like the "ghost" logos that identify television channels. The

watermark's purpose is to encourage people entering one Geocities

site to try other sites on the service.

But many Geocities members complained that the watermark made

their pages load more slowly on visitors' browsers, cluttered their

screens and obfuscated links.

So using the very tools that Geocities had given them to build

their Web sites, some members created anti-watermark pages, chat

rooms and mailing lists. When Brown turned the front page of his

Monty Python site black in protest, Geocities stopped featuring his

page. Other members got wind of this and turned his case into a

rallying point for the anti-watermark campaign.

The whole situation, Brown said, reminds him of Monty Python's

sketch in which a pet-store patron tries to return a dead parrot.

"The customer has a valid complaint, and the management uses every

trick available to avoid facing that fact," Brown said.

Such are the promise and the peril that come with trying to

build a business by giving a megaphone to millions of people.

Geocities is one of a growing number of "online communities" --

sites or services that allow people to publish Web pages and

communicate with one another by chatting, sending e-mail and so

forth. Such community sites now make up six of the 20 most popular

sites on the Web. Geocities is the largest, followed in descending

popularity by Tripod, Angelfire, Hotmail, Switchboard and Xoom.

Some advertisers are wary of placing their product next to chat

that as likely as not will turn sexual -- or on a page that today is

an affable tribute to Monty Python and tomorrow is a diatribe

against the host service.

"What gives us a nervous twitch is the fear that if a user has

a bad experience they will think negatively on our clients," said

Jonathan Adams, a media buyer for Ogilvy One, the online agency for

Ogilvy & Mather. "Even if 99.9 percent of the sites are squeaky

clean, it's that tenth of 1 percent that will wind up in the CEO's

lap."

|

|

Some Geo-citizens are displaying this ribbon to protest the company's placement of a "watermark" on their pages.

|

Bohnett, who has championed the right to free expression of

minorities as a board member of the Gay and Lesbian Alliance

Against Defamation, says that playing censor in chief for 2 million

people weighs heavily on him.

"A lot of what I'm doing has to do with being gay and part of a

minority that has not had an equal voice in society," Bohnett said

in an interview in March. "But we have to balance freedom of

expression with commercial viability. Otherwise all of this will go

away."

Bohnett has declined to comment on the watermark or any other

matter recently because Geocities is in a required "quiet period"

related to its planned stock offering. In May, Bohnett hired Thomas

Evans, publisher of U.S. News & World Report, to be Geocities'

chief executive. Bohnett remains chairman.

The impulse that created Geocities was more expressive than commercial. In the spring of 1994, Bohnett took a break from a career in software marketing after his longtime companion died of AIDS. Intrigued by the Internet, Bohnett and a friend, John Renzer, bought a $5,000 computer powerful enough to serve up Web pages and published a little site with a live picture of the Intersection of Hollywood and Vine and a few other locales.

Within a year, they seized on the idea of giving users free home pages and organizing them into "virtual" cities, arranged loosely by topic. Thus, when a new "homesteader," in Geocities' lingo, wants to set up a page, he or she selects a lot in a particular city. Those who are interested in cars move into Motor City; jazz fans choose Bourbon Street.

The most heavily populated of the 40 cities are Silicon Valley, about computers, and South Beach, a vast spring break-style party. But the most popular destination among visiting Web surfers is Hollywood, the home of most of the fan pages, including Brown's Monty Python page.

Most of the sites are simple, even hokey affairs, offering photos of pets, love poems, pie recipes and other matter that lived between the refrigerator and a magnet in the past. But some are much more elaborate.

"If you're a bank clerk by day and a Smashing Pumpkins fan by night, this gives you an opportunity to express yourself," Bohnett said.

|

Cybervisitors

A look at who visits and helps to create Geocities' Internet neighborhood.

|

|

|

Source: Relevant Knowledge

|

The New York Times

|

Once they expose themselves to the world, Geocities members closely watch the count of how many visitors their sites attract, and they express glee at receiving an e-mail from a far-off place.

"I was a ham radio operator in high school," Bohnett said. "It was exciting to collect postcards from people you talked to around the world. That is a lot of what the Web is about."

Even more surprising, people started sending e-mail to their virtual neighbors to comment on their sites and offer help.

Renzer, now the company's chief technical officer, said, "People actually go out of their way to become block captains, to join welcome wagons and to monitor chat rooms so they can have a neighborhood that is safe and clean."

Geocities now has 1,500 volunteer community leaders who help other members and watch out for offensive behavior.

"The community leader program is the perfect environment for folks with a 'helper complex,"' said Sherri Kaufmann, a housewife in rural Minnesota. She originally joined Geocities to show off pictures of her 10 children. Now she spends an hour a day on the computer in her kitchen watching over her corner of the "Picket Fence" neighborhood.

"We truly are a community of neighbors who help each other out," Ms. Kaufmann said. "I have made many friends here. Recently, my father became ill, and I was overwhelmed by the letters from the friends I have made at Geocities."

But even more powerful than the common human urge to help a neighbor, however virtual, is the sexual urge. Volunteers and Geocities' small staff spend most of their time rooting out pornography that sprouts constantly on members' pages, as well as other illegal or objectionable material.

"We've gone through seemingly endless debates about content guidelines," Bohnett said.

And, still, its rules are uncomfortable compromises: Political opinion is OK; hate speech is not. You can have a page about sex but no pictures of naked people, unless they are classic artworks or on pages about nudism as a life style. Most members can criticize Geocities on their pages somewhat, but community leaders cannot.

Similarly, Geocities has been in a constant battle with its members about how much of their pages it controls for advertising and promotion. Other protests arose when the service began superimposing advertisements over members' pages.

Geocities has not been able to fill the ad space that it does have. Last year, the company had only six advertisers. Now, after a reorganization of its sales force, it says it has more than 100. But its members' pages are only about 25 percent sold.

|

Michael Tweed for The New York Times

|

David Bohnett founded Geocities as a place to express views, "but we have to balance freedom of expression with commercial viability," he said.

|

Now, with a new management team drawn from larger media companies, Geocities is trying to find ways to turn its audience into cash. It has tinkered with the design of the site to create more places for ads and to keep surfers longer at Geocities, especially on those pages that attract ad rates with a high cost for every thousand visitors, like pages about cars and other expensive items.

And it is coming up with other sources of revenue. There are deals with online merchants like Amazon.com, which will sell books recommended on member pages, paying commissions to both the member and Geocities. There are services that for a fee let the most dedicated members build more ambitious and complex sites. And for those who want to set up business in cyberspace, it has started a program called Geoshops to display online storefronts for which it charges monthly fees starting at $25 a month.

Taken together, Geocities hopes all these initiatives will quadruple its revenue from $4.6 million last year to a range of $20 million to $25 million this year, Bohnett said in March. Stephen L. Hansen, the company's chief financial officer, said in March that he expected Geocities to break even next year.

But this rush to make money is leaving some members behind.

"Right now, I feel they are pushing commercialism a little too much with all the home pages inundated with ads and links to ads," said Sharyn Gleaves, who has built an elaborate site devoted to drumming around campfires.

Indeed, Brown says he is about to move his Monty Python site to another service.

Yet Renzer, the co-founder, argues that making money is just another aspect of Geocities' virtual vision.

"Everything in the real world should be mirrored in Geocities," he said. "What do you do? You go to bars. You talk to people. You find a date. But you also go shopping, and you have a job."

And, for that matter, you have virtual protests, boycotts and heroes as well.

Related Sites

The following link will take you to a site

that is not part of The New York Times on the Web, and

The Times has no

control over its content or availability. When you have

finished visiting this site, you will be able to return to this

page by clicking on your Web browser's "Back" button or

icon until this page reappears.

ick Brown did not set out to be anyone's hero. Simply wanting

to learn a little more about the Internet, he signed on two years

ago with

ick Brown did not set out to be anyone's hero. Simply wanting

to learn a little more about the Internet, he signed on two years

ago with