|

Remembrances By Ilona Bodo HUNGARIAN HERITAGE REVIEW, VOL. XX. 6 Part series, 1991

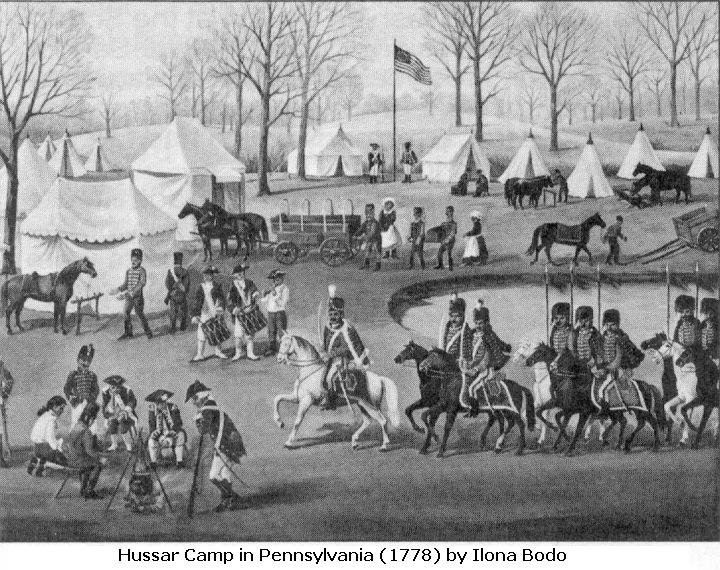

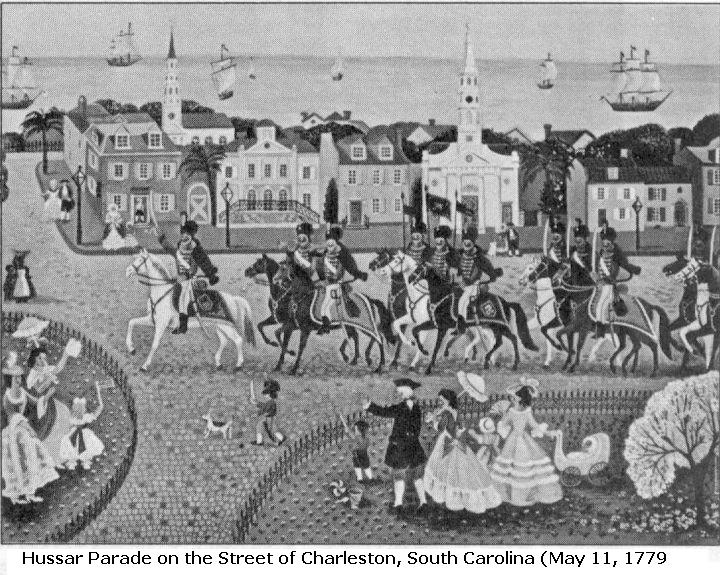

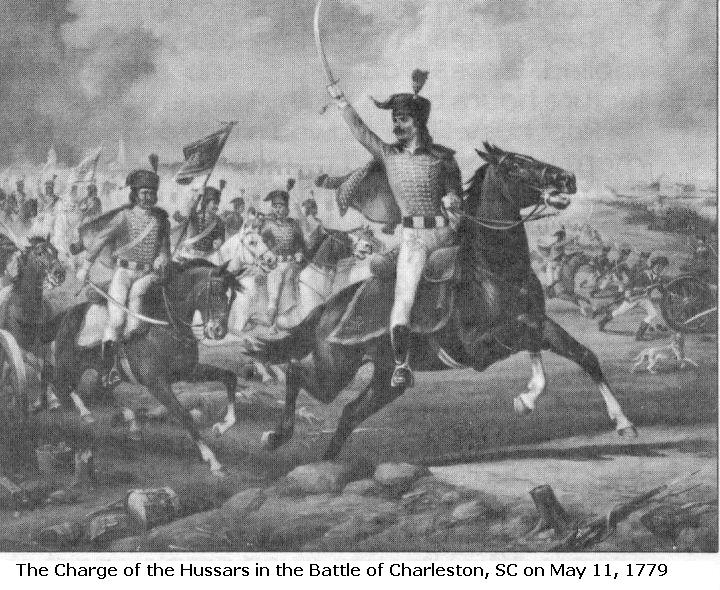

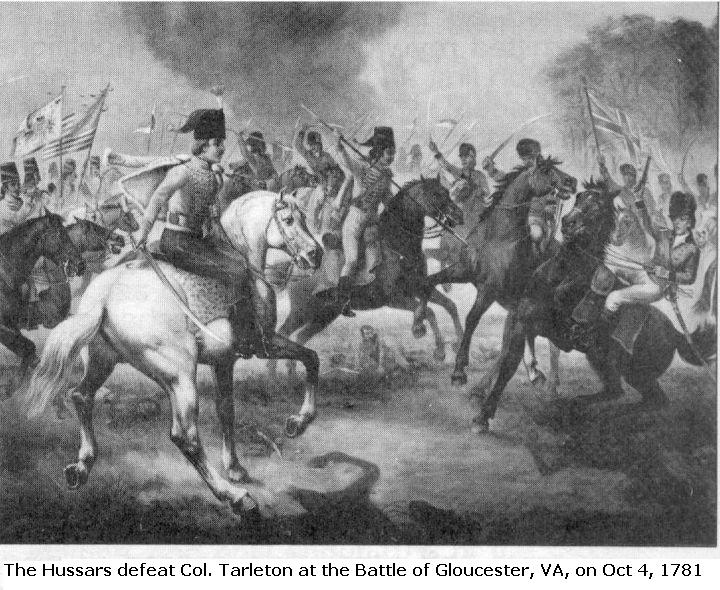

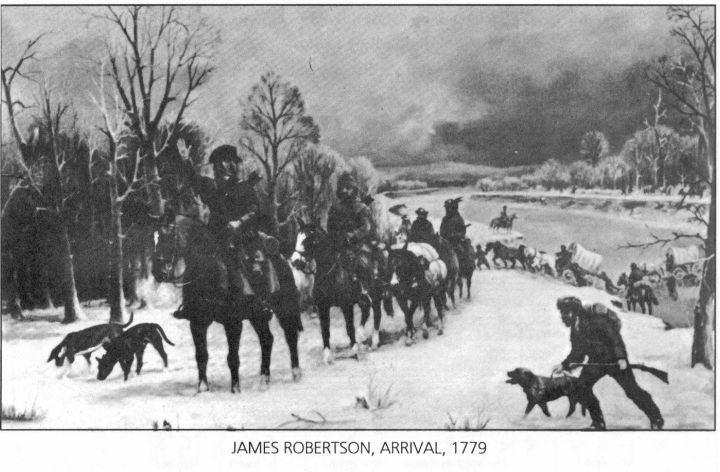

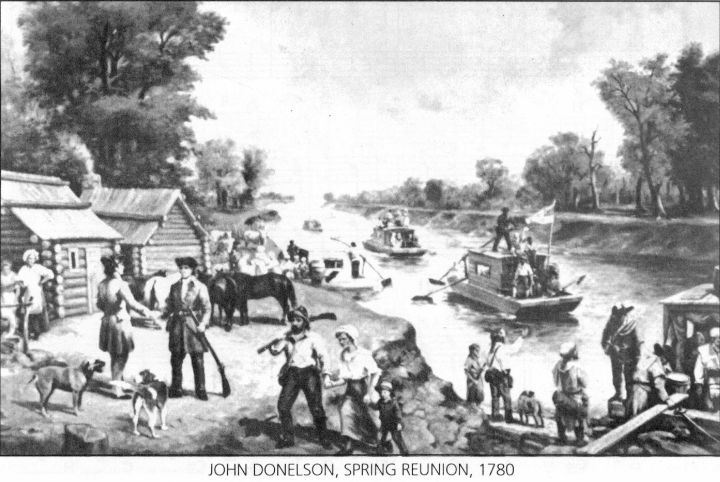

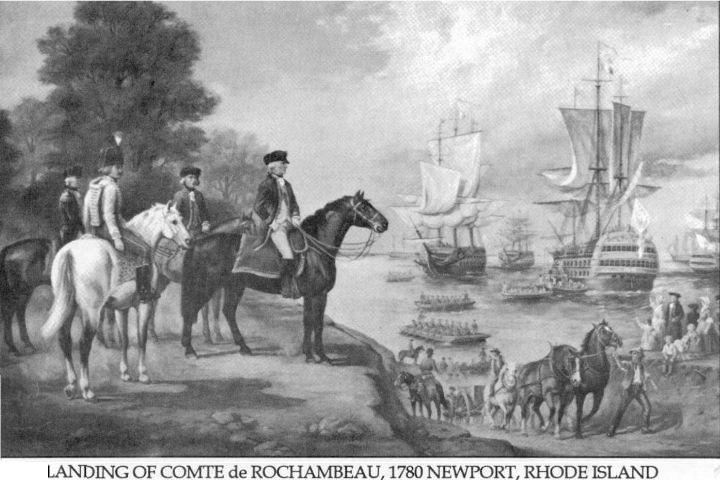

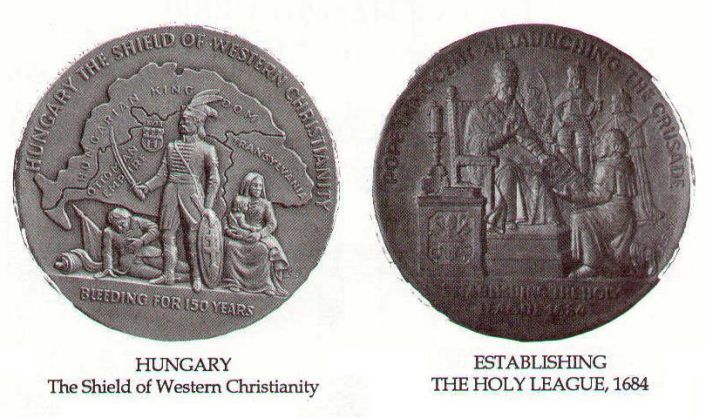

Part I Budapest 1945. The war had ended, leaving the country in ruins with buildings bombed and the people in large measure sick, hungry and homeless. But life goes on. One mild day in early September, I met Sandor at the School of Applied Arts. We were both curious about the news of events at the school. A part of the faculty and students had either disappeared or died. Many had emigrated. Everyone either mourned or buried someone. We, however, were young and healthy and now wished to pursue our studies. Sandor was studying to be a painter; I chose the textile field, having completed a four-year course in fashion design at the School of Industrial Design. During the war Sandor served for three years in the Hungarian Army as military cartographer. He had recently returned from Germany, which had fallen to the American forces. In 1941 Sandor had been admitted to the School of Fine and Applied Arts in the fine arts curriculum. His artistic interests were already apparent in his youth. He used to carve little figures, often cutting his hands so that even today the scars are visible. He was most interested in the violin. He even learned to play the violin by ear at an amateur level. He made his first violin from clay and later carved one from wood. At the age of six his carved instruments resembled real violins in both sound and shape. This zeal and interest in violins remained with him for decades until with the assistance of violin craftsmen and sound engineer experts he perfected his craft. His production and repair of violins provided welcome supplementary income during his school years. At his graduation, one of his professors raised the question of how Sandor could have graduated with honors when he did not seem to pay attention to the lectures. Sandor replied, "Yes, I carved violins during the lecture hours because my hands needed to be kept busy. This allowed me to concentrate more and increased my attention span." He made approximately thirty violins, which he also sold. At one time his friends called his violins "Bodo-variusz". From 1945 both of us pursued our studies at the School of Applied Arts, formerly the Academy of Fine Arts. Subsequently, in 1948 the school council dismissed Sandor as one with religious inclinations. The ax fell eventually on everyone who did not conform to communism. Circumstances forced him to accept a position with the military as a draftsman. Then in 1950 he was given employment at the State Bank Note in the design department. In the meantime, on his own, he learned etching and engraving. PART II In 1951 I received my diploma in applied arts (textile printing). Then Sandor and I were married. For an engagement present he carved me a small violin, complete with bow and case. Following our marriage I worked in a textile factory for almost two years. I received several awards for my designs, which also meant additional fiancial income. In 1953 our first son, Sanyika, was born. I remained at home after his birth and worked on individual textile projects. I submitted my work in textile competitions and won first and second place with them. My pieces, which were exhibited at the Museum of Applied Arts, were accepted in international exhibits as well, representing Hungary abroad in China, Poland and Czechoslovakia. I became an active member of the Art Foundation of Young Artists Collective Studio in Budapest. Eventually we acquired property in Buda and planned our first studio home. Sandor not only drew up the plans but assumed a large part of the construction work as well. Completion of the construction was interrupted when Sandor was accused of political agitation and hauled off to prison in 1954. He was sentenced to four years and spent eighteen months in the Kobanya Gyujtofoghaz. This is where the Hungarian aristocracy and the upper middle class, along with religious leaders, were imprisoned. The prison had a studio for artists. For the daily sum of twenty fillers (mere pennies) they painted portraits of Lenin, Stalin, Marx and Rakosi for the political officers. October 23, 1956 marked the beginning of the Hungarian Revolution and on October 31 the prison doors were opened. Sandor was free. Because of the subsequent suppression of the revolt and of the regime, on December 11 we left our country with nothing but the clothes on our backs, a paint box and our three-an-a-half-year-old son in our arms. We walked for five hours in sinking mud alongside the Russian tanks and watchtower. It was with apprehension and hope for the future that we crossed the Austrian-Hungarian border and embarked on a new chapter in our lives. We arrived in America on February 22, 1957. We waited for weeks in Camp Kilmer, concerned about the outcome of our fate. Finally the Calvary Baptist Church of Washington, D.C. assumed our sponsorship. They provided us a furnished room for one month and enrolled us in an English class. Actually, we needed at least six months of assistance in order to establish some sort of foundation in our lives. We found it very difficult to secure permanent employment in Washington. Then after finally finding work, Sandor was laid off after a three-month period. I, in turn, worked twenty hours weekly for ninety cents an hour. I was willing to accept any kind of employment so that we could have some supplementary income. Sandor painted portraits for literally pennies. He engraved silver plates and carved the state seal on gold cuff links. Our first studio apartment consisted of the mezzanine rooms of the headquaters of the American Hungarian Reformed Federation. The building was called "Kovats Haz" in memory of the famous Hungarian hussar colonel who served in the army of George Washington and gave his life in the battle of Charleston (South Carolina) in a fight for American Independence. Some months later, Sandor was commissioned by the American Hungarian Reformed Federation to make small bronze plaques of their past presidents. Years later that same organization would commission Sandor for two large plaques - one of Theodore Roosevelt and the other of Louis Kossuth. In March 1958, our second son, Lacika, was born - the first American citizen in our family. At about the same time we received an invitation from the publisher of the Baptist Sunday School Board in Nashville, Tennessee. We accepted the position they offered us and moved to Nashville in January 1959. Sandor worked for the publisher for three years as an illustrator and graphic artist. The appointment, while modest, provided a steady income and also gave us the opportunity to acquaint ourselves with the American way of life. PART III In the last twenty-five years our own art collection has grown along with our acquisition of antiques, giving our home a museum-like character. Another interesting phase of our work was made possible by the proximity of our home to equestrian activities. The countryside was a beautiful sight with the red-coated fox hunters' procession on the hunting field, the swift horses, the nervous packs of hounds and the jumps over hedges and streams. It is not surprising that we became interested in this sport. We attended the competitions, demonstrations, foxhunts, and we purchased technical books. Equestrian sports have a history of a thousand years - the Greek chariot races on vases; the Persian polo games; the army of horsemen in Chinese graves; the Renaissance paintings of troops; and the paintings of the French royal hunt - all rich stores of the arts. In the 1970's, paintings of equestrian sports were ranked among commercial art. The modern trend was for abstract paintings. Critics bolstered the influence of these works and promoted their inflated value. During this time, however, we advertised our own artwork in reputable magazines. Some readers took notice of us and we were successful in making some sales. Corporations and banks began collecting paintings from us. In 1971, the Honorable Guilford Dudley, the American Ambassador to Denmark, invited Sandor to participate in a joint exhibition to be held at the embassy residence in Copenhagen. Mr. Dudley is also an impressionist painter. In response to Mr. Dudley's invitation, Sandor exhibited his equestrian paintings. Invitations were sent out for the opening of the exhibit to members of the diplomatic world and to city and other officials. Ambassadors and their wives, member of society, intellectuals and city and state officials attended. Copenhagen's largest weekly magazine, Billed Bladet, featured the exhibit on a full page with illustrations. Our interest in historic painting and its study was inspired by our work on the restoration of the Hermitage, the home of Andrew Jackson, seventh president of the United States. The Hermitage is thirty-five kilometers from our home. Beginning in 1965 we worked for four years during the winter months on the restoration project. We restored the deteriorated yet valuable French wallpapers, and paintings with their original frames. The century old atmosphere of the building, the furniture, the tone of the paintings, and in fact the entire residence, was an American story rich in history. The original furnishings, documents, clothing and portraits of members of the family - painted in the style of stiff elegance by an artist friend Ralph Earl - contributed to a sense of history. The president's study and his old law books, his walking cane and high hat provided a magical experience. The restored paintings, the repaired and affixed wallpaper, the frames repaired and re-gilt to their original beauty are now all part of a museum rich in American heritage. Recently, state grants and private donations have made it possible to build a new Jackson Center with air conditioning, a restaurant and gift shop to accommodate visitors. We are happy to have been a part of preserving these historic treasures of the Old South. We are also encouraged to observe from year to year the care with which Americans endeavor to preserve their past for future generations. Other significant historic restorations which we undertook in the area include the paintings in the home of James K. Polk, eleventh president of the United States; paintings in the Parthenon in Nashville (the only replica of the original - the Cowan collection of nineteenth and twentieth century American painting. In 1974, the United States was quickly approaching the year of its Bicentennial as an independent nation. We did not, however, notice any artistic activity concerning this historic event. For us, the Bicentennial offered a richly interesting theme. We vigorously studied the history of America. We visited battlegrounds and historic cities. We purchased reference books, including some special editions. Sandor, of course, chose as his first painting on the Bicentennial theme "Andrew Jackson in the Battle of New Orleans." He worked for two years on a 50" x 72" canvas along with some smaller sketches. In 1976 Sandorís exhibit opened in the Fidelity Federal Bank Building in downtown Nashville. The bank purchased the painting of the Battle of New Orleans, and several others were sold as well. We displayed both the American flag and that of the State of Tennessee at the exhibit. They harmonized beautifully with the paintings. We arranged an elegant opening reception using bouquets of red carnations and white damask table cloths. To this day we take pride in our patriotism, and now when flags are displayed throughout the country we are glad that we were steadfast in our patriotic convictions. In 1978, Sandor, as a delegate of Tennessee, participated in the 200th Anniversary of the death of Laszlo Bercsenyi in Tarbes, France. Our governor sent a Tennessee State flag along with the official papers to the celebration committee and proclaimed May 20-22 as Bercsenyi Days. Count Laszlo Bercsenyi was a Hungarian cavalry general who at the invitation of King Louis XIV of France established the French light cavalry: the Hussar Regiment. These cavalry officers, under the command of Duc de Lauzon, had been recruited from all over Europe and participated in the Battle of Yorktown. Colonel Michael Kovats is another Hungarian worthy of mention here. On May 11, 1779, he fell in battle defending the city of Charleston, together with the Kovats Historical Society and the Citadel Military Academy, organized a memorial celebration. The Kovats Historical Society was authorized by the city to make the arrangements for the event. Sandor was commissioned as the official artist. For almost two years we were in the process of preparing a historic Kovats exhibit in the elegant Gibbs Art Gallery. Along with several other historic paintings, Sandor painted the heroic attack by Kovats on a large canvas. I contributed several large batik wall hangings and paintings of two street scenes depicting processions of cavalry. General Mark Clark, one of the greatest heroes of World War II, presided over the opening ceremonies of the exhibit for the week long celebration. On May 6, a mass, including a letter from the Pope giving his blessing to all who were present, was offered in the Cathedral by the Bishop. Rev. Christopher Hites, Order of St. Benedict, gave the celebratory address in Hungarian. The highlight of the celebration occurred on May 11 when 1200 students of the Cadet Academy presented a full dress parade on the square, followed by a reenactment of the Battle of Charleston. The celebration was concluded with a banquet hosted by the Citadel Military Academy where General Clark was the guest speaker. The wall behind the podium displayed Sandorís paintings - the Battle of Charleston and portraits of Kovats and General Casimir Pulaski, on loan from the Gibbs Gallery. The paintings from the Charleston exhibit were later shown in New York City on October 11 at the Kosciuszko House, the Polish Cultural Center in commemoration of the anniversary of the death of Pulaski. Later we took the exhibit to Atlanta, Georgia where, jointly with the Polish and Hungarian cultural groups, they had both fine and folk art exhibits along with historic presentations, folk dance demonstrations and a banquet in the City Cultural Center. Part IV During 1979-80, Nashville, Tennessee celebrated its Bicentennial. According to the records, the founding of Nashville is tied to two dates, to two individuals and to two seasons. In 1779 James Robertson and his group arrived on horse- back and wagon traveling over hill and vale. They crossed the frozen Cumberland River during the severe cold of winter and started to build small cabins so that shelter would await the women and children who would follow. Replicas of these small cabins are maintained on the banks of the river in the heart of the city to this day. On April 24, 1780 John Donelson arrived by raft with the families, having traveled about 1,000 miles for many months and suffering much hard- ship. On the occasion of the Bicentennial, the State of Tennessee marked the celebration with the reenactment of the Donelson arrival. The two arrivals, the unloading and the meeting on the banks of the river provided an outstanding theme for a painting. John Sloan, Jr., President of the First Tennessee Bank in Nashville, commissioned Sandor to do two large paintings of the founding of Nashville. Sandor designed a commemorative medal as well. One side of the medal depicted Genera) Andrew Jackson on horseback, patterned after the statue erected in front of the Nashville Capitol Building on the occasion of Nashville's 100th anniversary. In the background of the statue on the medal is the silhouette of the modern Nashville skyline. The reverse side of the medal portrays Robertson and Donelson shaking hands after the arrival of the raft. From the original 16" diameter plaster mold, Perfection Models Company foundry sand-cast a limited edition of six (6) plaques. The bank executives presented these plaques to the State Museum, the Governor s Mansion, the Davidson Court House and the Chamber of Commerce. We had two additional exhibits in the main branch of the First Tennessee Bank. It was here that I introduced for the first time my acrylics with historic themes - naive paintings but already leaning towards impressionism. Sandor exhibited his historic and equestrian paintings. The years of preliminary study and work on our part, the careful organization and the harmonious collaboration with the First Tennessee Bank brought successful results. The recognition we received in the press resulted in sales of many of our paintings. The exhibit also increased the public's interest in the bank. The First Bank of Tennessee took a leader- ship role in cultivating interest in American history by investing in the paintings. Part V The conclusion of the American Revolution took place at the victorious Battle of Yorktown. The Bicentennial celebration included the reenactment of the event on the original battlefield. Camps of tents, the procession of the different troops in uniform, the combat reenactment, and the parade of the military band offered an unforgettable experience. Six months prior to the celebration of the Battle of Yorktown, the French organized a military exhibit at the Yorktown Victory Center. The exhibit included uniforms, paintings, guns and prints - all relics of the times. Sandor prepared to paint an event in which the Hungarian hussars participated under the command of the French in the Battle of Yorktown. The French strongly supported General Washington in the final years in the fight for independence. Sandor had researched this historical period in detail but it was here at the Yorktown Exhibit that he gained access to a copy of the report on a military clash at which Duc de Lauzon, together with his legionnaires, defeated the English Colonel Tarleton and his British troops on October 3. Duc de Lauzon brought together the light cavalry of Hungarian hussars, the Polish lancers and the French and German infantry. The cavalry commander was Major Pollereczky of Hungarian descent. The theme of the painting portrayed the authentic cavalry combat during which Colonel Tarleton wanted to shoot Duc de Lauzon. While Tarleton aimed his gun, one of the Polish lancers stabbed the horse next to Tarleton, which fell against Tarleton's horse. Thus, the bullet went up in the air. This clash, which as later mentioned in both Tarletonís and Duc de Lauzonís memoirs, had not previously been painted on canvas. Because time was short, Sandor completed this large painting in four months. He delivered the painting, which was not quite dry, to the Daughters of the-American Revolution Museum in Washington, D.C. for the opening of the exhibit celebrating the Bicentennial of the Victory of Yorktown. The exhibit was officially opened by the French Ambassador. His Excellency Francois de Laboulaye. Sandor's painting remained with the exhibit for a six-month period. During the Bicentennial year, America experienced a renewed appreciation of its past and its history. New names and events came to light, some which had been forgotten for a century. Not even the textbooks mentioned the European allies and the service of their military volunteers and heroes. Among them was the forgotten Comte de Rochambeau, who with 6,000 well-trained soldiers, crossed the Atlantic by boat and was the commander of French troops. During his stay here he participated in one of the interesting phases of the final years of the American Revolution. The cavalry legion of Duc de Lauzon that came over with Rochambeau performed an outstanding service in scouting and liaison work between the forces of General Washington and Rochambeau. In honor of the European allies and their military volunteers, Sandor designed eight commemorative medals, which were produced in bronze and coated in 23 karat gold at our own expense. On September 3,1983 at the Bicentennial celebration in France of the signing of the Treaty of Peace at Versailles, Sandor represented Tennessee as the Ambassador of Good Will. At this occasion Sandor, in the name of the State of Tennessee, presented the eight commemorative medals in display cases to French President Mitterand, to Hobel des Invalides and to Qaude Manceronnak, Chairman of the Paris-Versailles Celebration Committee. The project of the commemorative medals had great significance to us. We were given the opportunity to place them in American museums and in university collections - the Smithsonian Institute, the Society of the Cincinnati Anderson House and Stanford University, among others, as well as in several leading European museums including the Vatican Museum. Part VI The 1686 liberation of Buda in Hungary after 145 years of control under the rule of the Ottoman Turks is one of the most significant events in the history of western civilization. In the Battle of Buda, soldiers of nine countries were involved in the Holy Federation, which was organized by Pope Ince XI. To commemorate the 300th anniversary of this event Sandor designed a series of five medals in the framework of "Hungarian Life and Its Future Movement." The five medals depicted the following significant events: 1) Pope Ince VI sends out the Holy Federation; 2) The united western troops gather at Párkany; 3) The Siege of Budavár; 4) The Fortress Combat; 5) Hungary as the Protector of Western Christianity. The series of medals was prepared with the assistance of Hungarian historians to assure authenticity of the portrayal of the historic events. The Commemorative Committee did not anticipate that Hungary would issue the appropriate commemorative medals. Sandor's research revealed that not one Hungarian was included in the heretofore issued several hundred medals to be found in Hungarian and Austrian museum collections. Sandor designed four medals depicting Magyar hussars. From the historical viewpoint this is the first series of medals depicting the struggle of Hungary under the rule of the Turks. The series entailed six months of intensive work and significant financial sacrifice. The Reverend Father Christopher Hites worked tirelessly to obtain financial help. Istvan Zolcsak, a Brazilian manufacturer, also provided material assistance to make the series a reality. Unfortunately, the project was concluded with a deficit because the leadership of the Hungarian immigrants in America, with political shortsightedness, censured the sale of the medals by waging a campaign in the press opposing them. From his political opposition, however, another idea was born - to use the subject of the medals on a large plaque, of Budaís Liberation. We donated this single-issue plaque to the Museum of History Budapest in the name of "Hungarian Life and Its Future Movement" in September 1987. In the absence of Dr. Laszlo Selmeczi, Director, Dr. Imre Bankuti, Assistant Director, accepted the plaque on behalf of the people of Hungary. Thus, it was the "Liberation of Buda" portrayed on a plaque together with the series of medals became a part of the American-Hungarian cultural exchange. Through the pursuit of history and art, we have re-established our own ties with our Hungarian heritage. In the land of America the struggle for freedom is a fabric woven from the histories of many people from many countries. It is the recognition of the sacrifices of so many that has deepened our convictions. |