THE SOLUTION OF AN AGE-OLD MYSTERY:

The Family Background As The Key To The Character And The European

Heritage Values of Colonel Michael Kováts de Fabricy (1724-1779),

Commandant Of The Pulaski Legion In The American War Of Independence.

-by-

DR. ELEMER BAKO

Hungarians in North America have an impressive history of their presence

on this continent. It begins with Stephen Parmenius of Buda (in Hungarian:

Budai Parmenius Istvan), a fine, young scholar and poet who lived at Oxford,

England. He joined the second America expedition of Sir Humphrey Gilbert

in 1583 as its official chronicler, and made, together with others, some

short, exploratory visits to the coastal area of Nova Scotia but has lost

his life there in a sea storm. However, a very fine, scholarly biography

prepared by two Canadian authors preserved his memory by offering proofs

of the outstanding qualities of his personality, his poetry and scholarship,

and secured for him a position among the writers of the age of discoveries

also.

Leaving here unmentioned several other important individuals of Hungarian

origin who enriched American civilization in the course of the following

hundred years, we move to the period of Hungarian history in the early

l8th century which is marked by the Hungarian war of in- dependence led

by the legendary Francis Rakoczi II (1676-1735), elected ruling prince

of Hungary and Transylvania, against the House of Habsburg in the years

of 1704 to 1711. Its events, leading personalities, political, constitutional

and ethical principles have been reported about, often in much detail,

in the excellently edited weekly issues of the first American newspaper,

The Boston News-Letter, which began publication in April, 1704. Thus, it

was no wonder that the Founding Fathers of the American democracy

including General Washington were fully aware of the nature

and values of the specifically Hungarian type of light cavalry service

named Hussars but also of the demands facing the commander of an army when

trying to establish a Hussar unit for his country.

The news about Hussar units reached this

continent in the l8th century via the numerous press reports from Europe,

particularly from Lon- don, and the military works published in France

and Prussia where numbers of officers (many of them high ranking) and men

of Hungarian origin served in the Hussar regiments of those countries.

Catholic Hungarians usually preferred the French service, the Calvinist

and Lutheran Hungarians the Prussia of Frederic the Great. As a con- sequence,

these "foreign Hussars" who were also political refugees and dissidents

(especially their Hungarian officers) often found themselves fighting their

former comrades-in-arms.

It was both a tragedy and glory of the Hungarian nation: brought nearly

to complete destruction as an independent nation during 160 years of Turkish

occupation of Hungary’s central regions and the ensuing warfare between

the German-Roman and the Ottoman empires on Hungarian ground, the nation

did not cease to resist these annihilating forces, neither did she stop

sending her best sons to foreign universities in her search for vital personal

and cultural contacts, knowledge and support of all kind in her efforts

to achieve freedom and independence. Many of these scholars ended up as

professors at foreign universities, officials in the administrations of

foreign countries, or (and this group is the most numerous) as officers

or soldiers in the armies of foreign rulers, from Madrid to St. Petersburg.

A prominent military man who offered his services for the cause of American

independence was the Hussar officer Michael Kovats de Fabricy (1724-1779),

Colonel Commandant of the Pulaski Legion in George Washington’s army.

His achievements in training American light cavalry and initiating

"Free Corps" tactics (known also as the precursor of modern guerilla warfare)

in the American service, earned him the name of "Father of Modern

American Cavalry", so recognized by the United States Congress and the

American Army. Prior to his sailing to America in early 1777, he was a

retired Hussar major in the Austro-Hungarian army of Maria Theresa, during

the years of 1762 to 1776. The previous l8 years of his life, however,

were divided between service periods in the Austro-Hungarian, French and

Prussian armies. In addition, while in retirement in Upper Hungary (present-day

Slovakia), he achieved considerable success and recognition as a training

officer of the voluntary troops of Polish patriots then organizing themselves

for the liberation of their nation in a movement called the Confederation

of Bar (so named after the place where it has been constituted). This was

the time when Kovats met and trained his future superior in the American

army, young Casimir Pulaski.

Michael Kováts de Fabricy in the Service of the United States

Hungarian historians conducting their research either in the United

States (like Eugene Pivany, Edmund Vasvary and others) or in Hungary (such

as Aladar Poka-Pivny and Jozsef Zachar) have cleared the ground around

many unknown details of the life and deeds of Michael Kovats de Fabricy.

We have almost full knowledge of his military career in the various European

armies, of his private and public life in Hungary, and the motivation for

his decision to join the cause of American independence.

The key to all above is given in a letter written by him in Latin, on

January 13, 1777, at Bordeaux, France, and mailed to Benjamin Franklin,

United States envoy at Paris. Following a short description of his military

life Kovats stated:

“I am now here, of my own free will, having taken all the horrible hard-

ships and bothers of this journey" (that s, from Buda, Hungary, via Italy

and France) "and I am willing to sacrifice myself wholly and faithfully

as it is expected of an honest soldier facing the hazards and great dangers

of the war, to the detriment of Joseph and as well for the freedom of your

great Congress. "

And, as he also indicated in the same letter, the Hungarian officer

sailed for far-away America without further delay.

This "Joseph" was the son of Maria Theresa, queen of Hungary and after

the death of her husband, German-Roman emperor Charles V, also empress

over the Imperial do- mains. Since 1765, her son, Joseph was ruling, at

the side of his mother, with the title of "Emperor" in full command of

all the military forces of the Empire including Hungary. He was the one

who changed his mother's opposition to the dismemberment of Poland in 1773,

and was well known for his ambitions to defeat Prussia and to regain power

over all German speaking lands of Europe forming a new, Habsburg-dominated

German empire. (Later, following the death of Maria Theresa in 1780 when

the son ascend- ed to the throne as emperor - but without the constitutional

recognition as king of Hungary because he was not willing to take the coronation

oath which would have compelled him to uphold Hungary's constitution and

the rights of the Hungarian nation, - he was branded even by Thomas Jefferson

a “despot" for his treatment of his subjects in Belgium, then part of the

Habsburg Empire.)

Such a ruler could not be suffered by Michael Kovats de

Fabricy, a former anti-Habsburg "freedom fighter", commandant of

a "Free Corps" and recipient of the highest military decoration in

the Prussian ar- my, the "Pour le Merit", and, by his association with

freedom loving Polish patriots, a supporter of Poland's in- dependence.

Also, because of Joseph's announced plans to recall most of the

retired officers to active service in preparation for new campaigns

against both Turkey and Prussia, Kovats had no other choice as an honest

soldier true to his own self but to leave the Austrian Empire and to seek

service somewhere else where the future could promise him a victory of

his avowed ideals: human freedom and national in- dependence. The only

land where he could nurse any hopes for such promises was an independent,

democratic United States of America.

For several reasons, however, Kovats' letter could not be forwarded

by Benjamin Franklin, neither could the American diplomat initiate any

recommendation on his own. The most important reasons were the, by then,

very angry and repeated reactions by General Washington to the employment

of any more of the foreign (mostly French) officers under his command who,

for higher rank and more substantial pay, were offering their swords for

the liberation of the American "colonists" from the rule of Britain. The

other reason was the hope on the part of Franklin and of other American

diplomatic representatives in Europe that, the queen of France being a

daughter of Maria Theresa, and, thus, a sister of Joseph, the future almighty

emperor of the Habsburg Empire, (who, for some mistaken reasons, was identified

by the progressive French personalities maintaining close contacts with

Franklin with the cause of reforms in France and Europe in general), they

might enlist Austria's support for the American cause, even if not to the

same degree as they managed to achieve it

with France. No matter what, a letter by an obscure, rebellious Hungarian

officer who declared to fight "for the detriment of Joseph", could not

be forwarded to the American Congress by Benjamin Franklin, the best American

diplomat in Paris. .

Consequently, Kovats' letter remained among the many other dormant pieces

of Franklin's European correspondence. Besides, the Hungarian officer has

left Europe without having presented himself in person to the American

envoy. Later, with a few lines of introduction by Major General Joseph

Spencer of Providence, Rhode Island, (dated April 30, 1777), Kovats paid

his respect to the Commander-in- Chief at his headquarters in Philadelphia.

The meeting did not bring the positive results the Hungarian officer was

hoping for. As Washington indicated in his reply to Spencer on May 17,

he has forwarded Spencer's recommendation to Congress but without any positive

support of his own because, owing partly to mistakes made by the interpreter,

some details in the past of Kovats appeared to be contradictory.

According to reports, Kovats functioned as a voluntary recruiting officer

for a Pennsylvania German unit during the summer, then, early in the fall,

he visited several settlements of the so-called Moravian Order of Lutheran

German Pietists who had their center in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, because,

as stated by the "Moravian Diary", members of both the male and female

branches of the order knew him either in person or heard about the Hungarian

officer through their own channels to Europe. In a few months, following

Pulaski's fiasco as commander of the cavalry units in Washington's army,

Kovats' excellent personal contacts with members of the Moravian Order

and, in general, with the German speaking population of upper Pennsylvania,

came as a real blessing for the Polish patriot: having fulfilled his request

for an "Independent Legion", Pulaski got Kovats appointed, at first, as

training officer, then as Colonel Commandant of the new unit.

It took the perseverance of the late Edmund Vasvary to find Kovats'

letter of Bordeaux among the "Franklin Papers" held at the Library of the

American Philosophical Society at Philadelphia. When it was found and published

by Vasvary, the important document helped to identify Michael Kovats de

Fabricy, and to prove his Hungarian origin. (However, some Polish historians

and public personalities are still trying to dismiss references

to his Hungarian background by pointing to the

Slavic etymological root of his family name, - the word `kovacs', that

is, `smith' being a Slavic loanword in the

Hungarian language.)

"Fidelissimus ad Mortem" (Most Faithful unto Death"), the closing phrase

in Kovats' letter to Franklin (the text of which, with its translation

into English or Hungarian, had been published by several authors in the

past) turned out to become a tragical reality for Kovats.

In early 1779, General Washing- ton issued an order to march the Pulaski

Legion to the South. Since the successful British invasion of Georgia in

late 1778, the City of Charleston, South Carolina, with its most important

port and trade contacts, became the next target for the British strategists.

According to Washington's (and the Congress') order, Brigadier General

Pulaski and his Hungarian Colonel Commandant led the only good cavalry

unit available for the defense of the American cause, together with the

Legion's infantry, to the aid of the Southern Department of the United

States Army.

The Southern Department, a continuously changing amalgam of mostly militia

units contributed by a number of the American states, was under the weak

command of General Benjamin Lincoln, a brave New England patriot, who has

submitted his resignation already to the Congress for poor health, particularly

for an incurable wound in his leg. Mainly for this lamentable physical

condition of the commanding general, and for his being a New England man

in charge of Southern militia units, the Southern Military Department was

in a constant state of turmoil. By the time when the Pulaski Legion arrived

to Lincoln’s headquarters, a large British army has already entered the

peninsula leading up to the City of Charleston. In fact, negotiations between

the city and the governor of the state on one side, and the British commander

on the other, for the surrender and the neutralization of the important

port city have progressed so rapidly that, by May 10, when its of the Pulaski

Legion entered the city, the British army, standing not far from Charleston,

was halted on the assumption that they have to wait only for the final

negotiation over the conditions of the surrender and the signing of the

relative document

The appearance of the Pulaski Legion, however, (made even impressive

for both the local militia and the British commander by some rumors that

General Lincoln, with more than 5,000 troops under his command, is approaching

the neck of the peninsula to cut off the retreat of the British forces),

worked real wonders. It recharged the will and courage of the city

population, changed the opinion of the city fathers, and, an audacious

attack led by Pulaski and Kovats against the approaching British outside

the city limits convinced the British commander of the eventually very

dangerous outcome of any further aggression against Charleston: he turned

around his troops of more than two thousand men, and, pursued by Pulaski's

decimated Legion and some local units, led them back to the fortified city

of Savannah, Georgia.

Unfortunately, however, Colonel Commandant Kovats, with a number of

the Legion's cavalry, found his death in the clash with the British on

May 11, 1779, right there, in the defense of Charleston. Mortally wounded

by a rifle shot, he fell from his horse, and was buried in the battlefield,

never to be found any more. His good friend and superior officer, Brigadier

General Casimir Pulaski, was fatally wounded later, during the ill-advised

attack on Savannah, and died of his wounds on October 9, of' the same year.

At the same time, the famous Legion was reduced to a meaningless, small

group of veterans, and never revived as a unit of the American army.

The great success of the Pulaski Legion by saving Charleston and the

American South for Washington. and the Congress was, initially, hailed

by the American Commander-in-Chief as the greatest glory which ever befell

American arms. But the formal, official recognition of the immortal heroes,

Pulaski and Kovats, and their comrades-in-arms

could never be issued by the highest authorities: as it turned

out, their reward would have involved the initiation of a formal investigation

into the circumstances of the surrender negotiations which could have amounted

to treason and secession on the part of those responsible for them in the

city of Charleston. Also, because of the death of the two commanding officers,

and the reduced status of the Legion, any such move on the part of those

responsible for the future of American democracy, appeared to be futile

and possibly dangerous. More than a century after the glorious performance

of the Pulaski Legion, representatives of the American Polish community

launched increasingly intensive campaigns for the recognition of

"their” hero, Casimir Pulaski. The most successful were those publicity

campaigns, which succeeded the tragic turns in Poland's most recent history

during and after the Second World War.

The public and official recognition of the merits of the Hungarian-born

officer came considerably later and in different forms.

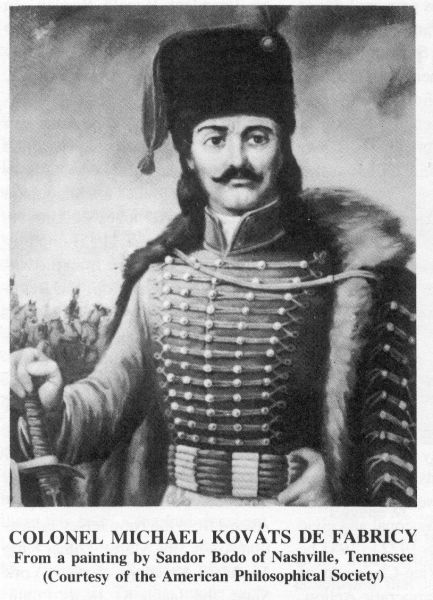

The Cult of Colonel Kováts in the United States and Hungary

The discovery that a Hungarian- born Hussar colonel had an important

role in the American War of In- dependence electrified American Hungarians

about half a century ago. Not bothered about the lack of authentical likenesses,

several American Hungarian artists have painted imaginary "portraits" and

created statues of the Hungarian hero on horseback. Also, a "Colonel Michael

Kovats de Fabricy Historical Society" was founded in New York City, with

branches organized in a number of other cities and states. The resulting

research activities led to several substantial publications, mostly essays

or well-documented articles, which grew out of the intensive correspondence

between researchers in America and Europe.

Some commemorative celebrations on both sides of the ocean encouraged

historical and cultural societies to hold "Kovats sessions" and other programs,

many of them in cooperation with the above mentioned "Kovats Society".

All these activities have greatly contributed to the rekindling of pro-American

sentiments in Hungary, - which was not a small success in those years when

Hitler's star rose to the Firmament of European politics.

Regardless of the lamentable fact that this organization was swept away

by the Second World War, the, by then, established cult of Colonel Kovats

has not lost its fire. The American Hungarian Federation, an umbrella organization

of most of the Hungarian- founded church, civic and cultural organizations

in the United States, with its center in Washington, D.C., developed a

cooperation with the Citadel, the Military Academy of the South, at Charleston,

South Carolina, and revived the cult of the Hungarian hero. A training

field of the Citadel was named after Colonel Kovats, and a marker with

a bronze plaque placed at its corner informs posterity of his immortal

merits in the service of the United States. In the course of the American

Bicentennial celebrations, his memory was recalled by the Citadel, the

United States Congress, the President of the United States of America,

the City of Charleston, the State of South Carolina, as well as by other

States of the Union, and last but not least, by the American Hungarian

Federation, both in the official Bicentennial Year (1976), and in the officially

proclaimed bicentennial anniversary year of Colonel Michael Kovats de Fabricy

in 1979.

These American commemorative events were happily echoed in Hungary whenever

the two great radio programs of the United States, the Voice of America

and the Radio Free Europe have informed the Hungarian public, often in

lengthy interviews with American Hungarian historians and other participants

in the commemorative programs. And, when the Holy Crown of Saint Stephen,

Hungary's first Christian king was returned to Hungary and the official

ad- dress delivered by Secretary of State Vance included a thoughtful reference

to Colonel Kovats, the Hungarian hero of the American War of Independence,

the, up to that time, cold attitude of Hungary's official authorities warmed

up, and a flow of public information in the form of valuable research articles,

books, commemorative addresses and stamps, began to create a new awareness

of the great personality of this Hungarian military man.

A Still Unanswered Question: Where Did This Man Come From?

All these commemorative publications and events, however, were constantly

overshadowed by an unanswerable albeit seldom expressed

question. It became rather painfully evident that nobody was in the position,

including this writer, to provide any answer to a routine question about

a prominent personality like Colonel Kovats: who were the parents and other

ancestors of this excellent military leader, and, in general, what was

the ancestral lineage, and, thus, what were the historical and genealogical

heritage traits of such a human monument of character, courage and dedication

to higher ideals?

Since I used to be in close contact with the late Edmund Vasvary, one

of the foremost researchers of Colonel Kovats’ life story and an eminent

creator of the "Kovats lore” in America, I am in the position to

report on the near desperate state of mind of this great student of American

Hungarian history who, while trying to give his best efforts to his task,

the writing of a complete and reliable biography of the Hungarian colonel,

he was still not able, up to the very last day of his life, to serve his

readers and the scholarly public with the names of his hero's parents,

let alone to provide information about the history of his ancestors. (In

fact, a biography of Colonel Kovats, in preparation by me since a number

of years, could not be completed and published for lack of the same essential

personal data.)

As it happened when Edmund Vasvary had found the Kovats letter among

the "Franklin Papers" at Philadelphia, enabling him to

conclusively identify Colonel Kovats as a Hungarian in General Washington's

army, "Fate" moved its hand again, this time involving me.

As I have already informed the American Hungarian public via a bilingual

journal entitled Testveriseg - Fraternity (vol. 59, no. 1-3, Jan. - March,

1981, p. 19-20) published by the Hungarian Reformed Federation of America,

a fraternal insurance company in Washington, D.C. (which has also published

the original Kovats letter discovered by Edmund Vasvary), I happened to

meet an old Hungarian friend of mine, Dr. Laszlo Keszi Kovats, of Budapest,

at an international congress of researchers of Finno-Ugrian peoples and

languages, held in August, 1980, at Turku, Finland, the ancient university

city of that country. When he was inquiring about my cur- rent research

activities, I have mention- ed, among others, my work on the biography

of Colonel Michael Kovats de Fabricy. With a good chuckle, he gamely remarked:

"And, as all other American Hungarian historians, you don't even know who

were the parents of Colonel Kovats?" With a demure expression in my face,

I admitted that, yes, that's the fact. Then, as a good friend, he smiled

at me, telling that I better turn to him for information because he comes

from the same ancestral background as the famous Colonel, and he would

be willing to prepare for me a copy of a long, 17-page document, originally

written in Latin by an ancestor of his, Stephanus (Istvan) Kovats de Keszi,

town notary at Tiszacsege, Hungary. Basing his final text upon an earlier,

mid- l8th century version of the Kovats family history, prepared by a relative,

Gabriel (Gabor) Hegyi de Zadorfalvá, a county notary of Heves and

Szolnok counties, Stephanus Kovats de Keszi updated his documentation,

ending it with the year of 1783, that is, four years after the tragic death

of Colonel Kovats in America. Then, upon completion of the family history,

it was deposited in the famous family archives of the Vay family (which

also housed thousands of other documents important to numerous Hungarian

noble families mainly of Eastern Hungary) where it remained for more than

150 years without being published or even registered and analyzed for its

contents.

In view of the limited space available for this article, I don't wish

to fill the pages of this journal with the full story of how my friend,

Dr. Laszlo Keszi Kovacs has found and copied the original family history

in the family archives of the Vay family at Tiszaberkesz, Hungary, in 1941.

According to that document, a copy of which, made by Dr. Kovacs for me,

is in my possession (waiting to get published in full in my Kovats biography

now in preparation), the family's first known ancestor, Johannes Besenyo

" became a "faber ferrarius" (iron smith), mentioned also as "Kowach

Regis", meaning the "King's smith", and was rewarded by Hungary's king

Charles Robert, of the Italin Anjous (Angevins), with a family domain in

1331, thus elevating him into the status of nobility. His descendants in

succession became prominent civil servants, military leaders and prelates

of the Roman Catholic Church. In 1479, Hungary's great Renaissance king,

Matthias I (Hunyadi, named also Corvinus) rewarded the family with a beautiful

coat-of arms, a copy of which, explaining its details, is published with

this article. The same document informs us also how subsequent generations

of this Kovats family served a long succession of Hungary's monarchs, the

legitimate kings of the various ruling houses including the Habsburgs,

as long as they have solemnly promised to uphold the constitution of the

country and to defend the nation's freedom and independence. And, when

they failed to do so, members of this Kovats family joined the many thousands

of Hungarian patriots, and supported the efforts of the elected princes

of Transylvania (up to and including Francis Rakoczi II in the early l8th

century) when the rulers of that small but independent-minded remnant of

the powerful medieval Kingdom of Hungary felt compelled to fight the Habsburg

kings of Hungary in order to force them again and again to sign "peace

treaties" with Transylvania and to promise anew to honor their solemn oaths

taken as constitutional kings of the Hungarians.

In the place of a lengthy narration of the Kovats family history, the

next part of this article is a sketch of the ancestral lineage of Colonel

Kovats which contains only the direct ancestors of the Colonel and some

other persons whose memories could have influenced the Colonel’s own character

development.

Characterizing the sons of Emericus (Imre) Kovats de Keszi and Kaal,

father of Colonel Michael Kovats de Fabricy, the document's compiler, Stephanus

(Istvan) Kovats de Keszi made an interesting statement. The English version

of the original in Latin follows verbatim:

"Excelled among them this Michael, who was a prominent soldier, reaching

the position of a Free Corps commander, and fighting in many campaigns,

in the lands of foreign nations, - under the assumed name of Michael Fabritius

Kovats, - and he became a victim of death there also; this Michael Fabritius

Kovats, - correctly, Kovats of Keszi and Kaal - had a son, George (Gyorgy)

whom he begot with the noble lady Franciska, daughter of Sigismund

(Zsigmond) Merse de Szinye."

This short remark was penned down by the young family chronicler four

years after the heroic death of the Hungarian-born Colonel Commandant of

the Pulaski Legion. It misses only a couple of relevant details. The Colonel's

son, George died at an early age, well before his Father had left Hungary,

by which time the parents had already separated owing to the fathers frequent

absences from the home because of his involvement in the training of the

Polish patriotic forces. The mother, Franciska Merse de Szinye never remarried:

she remained faithful to the memory of her husband.

Alas, the last important "mystery" in the life of the famous Colonel

has found its documented explanation. Now we really know where "he came

from", what were his family heritage values, the ancestral "images" which

motivated him, and the elements of his European culture which enabled him

to remain "Fidelissimus ad Mortem" (Most Faithful unto Death) to a cause

which was adopted by him as his own.

EDITOR'S NOTE: Because of space limitations, we could not include Dr.

Bako's list of source references, description and illustration of the commemorative

stamp issued by the Hungarian Post Office (1982), or his description and

illustration of Colonel Michael Kovats de Fabricy's Coat-of- Arms. However,

if any reader would like to obtain these, we would be pleased to forward

photocopies.

|