CONTENTS:

VIROSTKO CLEANS UP IN FIRST EVER MAVS CONTEST

PRINCETON-BY-THE-SEA - At the end of the long and grueling day, it took a Flea to conquer a mountain.

Darryl "Flea" Virostko, a 27-year-old surfer from Santa Cruz with a strange nickname and an even stranger hairstyle - bleached platinum with dark leopard spots - earned a place in surfing history by winning the first Men Who Ride Mountains contest Wednesday at Mavericks, the surf spot off Pillar Point known for its enormous, deadly waves.

Virostko, one of only 20 surfers invited to compete in the event, thrilled both spectators and judges with a wicked drop-in on one of the biggest waves of the day - possibly a 25-footer. He caught an updraft and became airborne as he descended, then caught his balance and finished the ride smoothly.

For his courage and technique, Virostko was given first prize, which was to have been $10,000 but was upped to $15,000 by Quiksilver USA, the contest's sole sponsor.

"There was a lot of camaraderie out there," said Virostko, looking a bit embarrassed by the glare of TV cameras. "A wave would come, and they'd all shout, "You got it! You got it!""

Asked how he got his nickname, Virostko said Vince Collier, another competitor from Santa Cruz, had given it to him when he was young. "He said I looked so tiny on a wave I could have been a flea."

As if on cue, the 38-year-old Collier interrupted in a booming voice at the back of the press conference: "Ladies and gentleman, Flea Virostko!" And the Santa Cruz contingent erupted with riotous applause.

Later, Collier declared that given Virostko's skills at both acrobatic and big-wave surfing, "He's probably the best surfer in the world right now - not just Santa Cruz."

The day did belong to surfers from "the Cruz," who took five of the top seven spots. Coming in second was Richard Schmidt, 38, of Santa Cruz; third was Ross Clarke Jones, 32, of Australia; fourth was Peter Mel, 29, of Santa Cruz; fifth was Jay Moriarity, at 20 the youngest competitor, from Santa Cruz; sixth was Josh Loya, 30, of Santa Cruz; and seventh was Brock Little, 31, of Hawaii.

Three of the surfers invited to compete were over 40 - including Dr. Mark Renneker of Ocean Beach, a cancer specialist and big-surf expert - and there were a handful of 20-somethings. The average age seemed to be early 30s.

The only criteria used to determine who would get the coveted invitation?

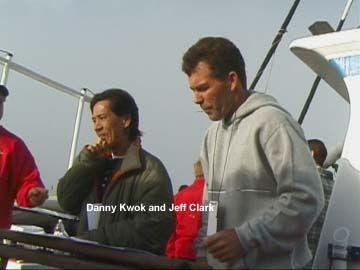

"Experience," said contest director Jeff Clark. "Whether they've surfed a lot of big waves, it's a whole different ball game than what most contests call for."

Indeed, only a tiny fraction of all surfing enthusiasts want to challenge themselves by surfing waves that are potentially lethal. A tinier fraction than that want to take on the likes of Mavericks. Until five years ago, Mavericks was a secret spot, known only to a few. But it's now considered among the top big wave spots on the planet - up there with Todos Santos in Baja California, the North Shore of Oahu in Hawaii, and J-Bay in South Africa.

Mavericks also is known as possibly the most dangerous surfing spot in the world, partly because of its proximity to huge rocks planted in the lineup, and also because of the sheer volume of water that rises up when the mighty Pacific meets the reef half a mile from Pillar Point some time between November and March. Heavy, green and opaque, it's a wave that really does look like a mountain.

The danger of the place was brought home in 1994, when a huge swell came up just before Christmas, drawing surfers from around the world. Included in that group was Mark Foo, a celebrity Hawaiian surfer with his own TV show and world renown. Before the end of his first day at Mavericks, he was dead, after probably hitting his head during a fairly routine wipeout.

"Yeah, Mark's death was a reminder that we should never take this place for granted," said Clark, shaking his head.

Contest organizers had been waiting since November for conditions to be right. Finally, the contest was a go when this week's storms generated a swell at Mavericks.

Clark had sole claim to Mavericks for more than a decade and a half, growing up within view of it and surfing it as a teen when no one else would. The only person he knows of who surfed it before him was a Half Moon Bay local named Alex Matienzo, who lived there in the '60s and who owned a German shepherd named Maverick.

As the story goes: the day Matienzo decided to give the break a whirl, Maverick paddled out into the heavy surf with him as he often did. But Matienzo returned the enthusiastic pooch to the car, concerned for his safety. The break was forever after called Mavericks. Wednesday, the crowd of several hundred who had gathered in anticipation of the event could have used Maverick for entertainment. The contest was postponed for four long hours while everyone waited for a heavy fog to lift. (Organizers noted that surfers needed to be able to see the rocks for safety reasons.)

Oh, but you could tell the waves were out there, somewhere on the other side of the gray screen. The thunderous noise attested to the size of the monsters.

By the time the fog cleared, about noon, and the tide had come in, the surf had gotten smaller. But even an average day at Mavericks is bigger than most. By the end of the afternoon, three surfers had been wiped off their boards and into the "boneyard" - the no man's land between the jagged rocks. They were fished out by Water Patrol members on personal watercraft, and all continued surfing.

Because of the late start, there were no semifinal or final rounds. Everyone was judged on performance in the individual heats.

Everyone seemed pleased with the results - doubly so for the up-and-coming Virostko, who said quietly that he wanted to dedicate his win to his friend Sky, a 23-year-old man battling cancer.

"We shaved our heads together out of solidarity - and this is how mine turned out!" he smiled.

It was right around the middle of November last winter, the first really heavy day of the Maverick's season, and the story wasn't in the lineup. It was on the cliffside, where three men stood watching.

Grant Washburn, Richard Schmidt and Jeff Clark represent the pinnacle at Maverick's, as capable as they come. They never made a move for their wetsuits that day because the place was 20-25 feet with contrary winds and out of control.

Left to his own devices, Washburn might have hit the water. Schmidt probably would have joined him. But they thought twice when they saw Clark in full retreat. This is the man who pioneered Maverick's, rode it alone for nearly 15 years, so there's hardly a question about his courage. "If Jeff thinks it's too dangerous," said Washburn, "well, then I'm gonna think it's too dangerous."

As they watched the scene unfold, Clark's fears were totally justified. Josh Loya dropped fearlessly into a set wave and took the worst wipeout of his life, an incident that diminished his big-wave bravado for weeks afterward. Mike Brummet, the young backside charger out of Santa Cruz, got about halfway down the face when he was launched into mid-air and pummeled without mercy. Maybe one other surfer took off that day, on any wave. It was just too heavy.

This is why Clark is the perfect man to run the upcoming Quiksilver contest at Maverick's, with a waiting period running through January 27. "I won't put anyone in a position I wouldn't put myself in," says the 41-year-old Clark. "It'll be a great day, a hard-core day, but the kind of surf that lends itself to fun and performance surfing. Maybe 15-18 feet, with some 20-foot sets, out of the northwest. A lot of contests can afford to wait for the biggest day possible. We can't do that here. When it gets that big, people are just sitting in the channel, not even going near the peak."

As most everyone in the big-wave arena knows by now, Clark's 20-man field has the look of class and experience. He wants just five surfers from outside the area: Brock Little, Ken Bradshaw, Ross Clarke-Jones, Tony Ray and Evan Slater, all of whom have surfed Maverick's before. The others will be locals. From Santa Cruz: Schmidt, Loya, Peter Mel, Flea Virostko, Vince Collier, the brothers Wormhoudt (Zack and Jake), and Jay Moriarity. From Pacifica: the highly respected Matt Ambrose and Shaun Rhodes. From the wilds of San Francisco's Ocean Beach: Washburn, Steve Lowrey and Mark Renneker. And from the pages of underground lore, Ion Banner from Half Moon Bay and Don Curry from Monterey. (Those familiar with the latest surf-magazine articles will notice an expanded field. Collier, Lowery and the Wormhoudt brothers were added to the main list after its original release.)

"This contest is all about the guys who have really devoted their surfing to Maverick's," said Clark. "We've seen a lot of guys hit the scene. They all got boards, they went out and saw the reality of the place, and they sold their boards (laughter). Then there's the guys who had the sack to go out there, and once they'd done it a few times, they knew the game and how much more they had to prepare."

I had a guy paddle up to me the day Mark Foo died (in 1994)," Clark went on. "He goes, 'I'm so scared!' I told him, 'Get away from me. Get out of the water.' I don't want to be around anybody who feels like that, especially out there. The guys in this (Quiksilver) contest are the ones who go out there with full confidence in their ability."

Clark's alternate list carries its own relevance, for it's a way of honoring some of the locals who might otherwise oppose the contest scene. For a variety of reasons -- attitude, injuries, dubious K2 priorities, misplaced publicity, a lack of experience or issues more personal -- such Maverick's veterans as Jim Kibblewhite, Keoni Watson, Taylor Knox, Chris Malloy and Bob Battalio did not make the cut. These are the ones who did, in the order they will be selected if any of the main-list entries can't make it:

1. Kenny (Skindog) Collins. Part of that rare breed of surfer who shreds small waves, complete with radical aerials, then moves comfortably into the big-wave arena. He joins Mel, Flea and Loya in that company from the rich pool of Santa Cruz talent. Last Jan. 30, when Maverick's broke at a horrifying 25-30 feet and Mel needed two attempts just to reach the lineup, Collins was one of the few surfers out there. "He didn't really go on the bombs," said Clark, "but not many did."

2. Colin Brown. Probably as talented as any surfer from the Ocean Beach-Maverick's crew. "This guy just rips," said Clark. "He's so talented. I know Doc (Renneker) has had some reservations about surfing the contest, and if that's the case, I'd go with Colin in a second." People like Renneker, Washburn and Brown have their own agenda at Maverick's. They're not preoccupied by the morning sessions, when the light is perfect (for photographers) and the Santa Cruz surfers arrive in full force. You're more likely to see them in late afternoon, with a bit of wind up but the waves still perfect and only a handful of guys in the water. That's the definition of a Maverick's local.

3. Mike Brummet. Out of nowhere, or so it seemed, this Santa Cruz resident took the place by storm last winter. He was by far the most committed backside surfer, to the point where if any goofy-foot took off on a bomb, you just assumed it was Brummet. Some felt he was a little too interested in the $50,000 K2 payoff last winter, but the bottom line is that he took off on waves that most surfers rejected out of pure fear.

4. Gary Elkerton. Out of all these names, both on the main and alternate lists, Elkerton is the only surfer who has never ridden Maverick's. He's one of the all-time performers in big Hawaii, and he was a deadly competitor in Triple Crown events there. While a bit out of the mainstream lately, he hasn't lost his big-wave stoke. "To be honest, I don't like the idea of anybody being in this contest if he's never surfed Maverick's," said Clark. "Elkerton is a Quiksilver guy. His reputation speaks for itself, but it's a concession we made to Quiksilver."

5. Rod Walsha. Part of Clark's original crew at Maverick's in 1990, along with fellow Pacifica surfers Ambrose, Rhodes, Kibblewhite and Brent Heckerman. "You may have not heard of these guys, but they're as gnarly as they come," said Clark. "Walsha's a total animal. He's a black belt in tai chi, just a bone-and-muscle kind of guy." Added Ambrose: "If you're talking about taking off on big waves, I'd put Rod right behind Flea and Peter Mel. People know it from back then. Rod was takin' off on 20-footers, not making 'em sometimes, and coming right back out."

6. Chris Brown. He got some dubious publicity in '94 when, after watching Moriarity take that wipeout for the ages, he paddled back to the beach in horror. But Brown couldn't stop thinking about Maverick's. He launched a fresh assault last winter and gained a lot of respect, particurly on an air-drop he nearly pulled off on a 20-foot wave. "I think Chris is still a little bit scared out there, but he's stoked," said Clark. "He's a blast to be out with. He's like a cartoon."

7. Mike Parsons. Deeply shaken by the events of Dec. 23, 1994, Parsons hasn't been back to Maverick's. He's made a winter home at Todos Santos, where everyone considers him the best around. "This is a guy who fell off a wave at Maverick's, had the lip hit him in the chest, got blown through the rocks, then spit back through the other way," said Clark. "And then Mark Foo dies on top of that. So I can understand him being a little shook up. But I put Parsons on the list out of respect. I think a good session out there could turn him around."

8. Mark Sponsler. This East Bay surfer is known mostly for his Stormsurf website, considered the No. 1 source of big-wave forecasts among the Maverick's crew. "But he's always out at Maverick's," said Clark. "This is a guy originally from Florida, and I've seen him out there by himself in the afternoon at 18-20 feet."

9. John Raymond. While not a super-talented surfer, he became a star with his hilarious and right-on interviews from Washburn's film documentary, "Maverick's." For years he rode enormous Ocean Beach without the slightest fanfare. Now this 39-year-old bankruptcy lawyer has dedicated his life to Maverick's. Just for fun, he keeps a chart on the number of times he and his friends surf Maverick's ... and both Raymond and Washburn surfed it 62 times last winter alone. If it happened at Maverick's, chances are John Raymond has witnessed it.

10. Steve Dwyer. Yet another Ocean Beach veteran from the East Coast (along with Washburn, Battalio, Raymond and Christy Davis), Dwyer made his mark during the epic swell of '94. He put it all on the line, getting the waves of his life and taking his worst-ever wipeouts. The experience lifted him to the highest level, but it also made him acutely aware of his mortality. At last, an honest man. At the age of 38, with a wife and kids, Dwyer says, "I had a couple of experiences out there that really humbled my butt. I started thinking about my family. I became more choosy. I got some demons. It's hard to get used to the fact that you're slowin' down. But I want to be there when the jerseys go on and those guys are goin' off. If I don't get in (as an alternate), I'm going to love watching it."

11. Christy Davis. By trade he's a 45-year-old environmental chemist from Moss Beach, only a stone's throw from Maverick's. But he leads a fascinating double life, surfing big Ocean Beach and Maverick's at every opportunity. Not a great surfer, and he's the first to admit it, but Davis loves the thrill and the experience, and on a 15-18-foot day, he'll get his share of waves. "I'm really against contests out there," said Davis. "But to be selected by Jeff on this alternate list . . . that's really an honor."

12-13. Tom Powers and Dave Schmidt. Neither man has surfed Maverick's in recent winters, but they were chosen for their historical significance. Back in 1990, on the same January swell that brought the all-time Eddie Aikau contest to Waimea Bay, they were the first two surfers to join Clark in the Maverick's lineup. Schmidt, brother of Richard, went right off the scale with his backside riding. "He was out there on an 8-4 and making unbelievable snap turns on huge waves," said Clark. "To this day I haven't seen a backsider pull maneuvers that sharp."

As expected, there was some behind-the-scenes quibbling about Clark's entry list, revealing sporadic cases of ego damage. Now, with the contest at hand, the emphasis has shifted to pure stoke.

Reef Brazil pulled out of its February contest slot -- a source of great relief, since Reef had no concept of Maverick's inner workings -- and the Clark/Quiksilver combination has produced an ideal-sounding event. Even with four additional surfers, the one-hour heats will have just five men, a vastly improved setup over the crowded 11-man heats witnessed at the Eddie Aikau contest in 1990. "That's just too many guys to put in the lineup at Waimea," says Bradshaw. "At Maverick's there's a lot more room. And to have just for other guys in the lineup with you ... that's perfect. Nobody can have any excuses."

A couple of Quiksilver contest tents will be set up on land, but essentially, this event will be run strictly from the water. Some questioned Clark's judging format, because without any judges on land, it would be impossible to see (a) a surfer going left or (b) someone screaming through the long inside section. But then you read the fine print on the press release:"The surfer that takes off on the biggest wave at the deepest point, and makes the drop, will receive the highest score."

In other words, long rides don't mean very much. Just go hard, go deep and make that bottom turn. This will be encouraging news for Brock Little, who took the biggest and heaviest waves in the storied 1990 Aikau, only to finish second to Keone Downing, who rode many waves flawlessly but didn't catch the bombs.

Who's the favorite at Maverick's? Hard to say. Mel has the best combination of talent and desire. Virostko simply doesn't care about anything, especially the consequences of a late takeoff on a 20-foot wave, and he could steal it. Washburn has made incredible strides over the last three winters and has added a carving, flowing style to his Maverick's riding. Schmidt is the old master with a lot of history. Banner, Curry, Ambrose and Rhodes are the soul-surfer guys who spent their lives riding massive surf without fanfare. Loya, Slater and Moriarity are forever etched in Maverick's lore from their performances in '94.

All that plus Bradshaw and Little, too? The imagination runs wild.

One of Renneker's big concerns was the safety angle, and the lack of a solid rescue/emergency system at Maverick's. Although several jet-ski operators have shown the guts to go into a churning whitewater pit to make rescues, "We really need a full-blown system in place," says Renneker. Quiksilver has taken an impressive first step, recently calling on Brian Keaulana, Terry Ahue and other Hawaiian Ocean Safety mainstays to visit Maverick's and plot contest strategy.

The reality is that priorities change during the biggest swells. It's conceivable that the Keaulana & Co. will be fully occupied in Hawaii when Quiksilver wants to run the Maverick's contest. The Aikau event could be a factor, or one of those "mysto" days like last Jan. 28, Big Wednesday, when the North Shore broke at 30-40 feet with perfect conditions.

"It might be a little tricky, but since Quiksilver also runs the Aikau and really wants the Hawaiians over here for Maverick's, I think we've got a pretty good chance," said Clark.

Here are assorted comments on the Men Who Ride Mountains contest, as it will be called, from some of the surfers involved:

DON CURRY: "You have to like Clark's entry list. It looks like the lineup on a big day. I have to say I'm a little nervous, because I've never competed in a professional contest in my life. But it's gonna be great, being out there with such a solid crew. You don't want a bunch of green guys out there, doing stupid things and risking their safety. This is a rare opportunity to give some people their just due. I'm just stoked that I'm one of 'em.

"Will this change the atmosphere at Maverick's? I really don't think so. I always feel good about the vibe up there. I don't think a well-conceived, one-day event will change that."

MARK RENNEKER: "I actually believe more than anything in sharing the ocean with everyone. That's what I love about Ocean Beach. It's a public beach, and damn the pissmouth sourpusses who somehow think that other people aren't entitled to surf there. So the arrival of a contest automatically breaks that rule, even if it's only for one day. You've got a structure that excludes people. Some winters we only get four or five really great days, and now you're losing one of 'em. I have a hard time with that.

"I've been asking myself, why go along with it? Why have complicity with the process? And strangely, I'm curious to see how it comes out. I'm part of this, whether I want to be or not. So to be a dissonant, on the outside of it all . . that would make me nervous. I think I can do a lot more to protect Maverick's -- particularly in the realm of safety -- if I'm actively involved.

"The Hawaiians have made great advances in water rescue, and we need to have our people trained. I've talked to Brian (Keaulana) already about the education he can bring to our area. If it comes in a few days early and takes some of our guys around with their jet-skis and puts 'em through a course, that would be fantastic. Everything about water rescue and the emergency medical systems is about rehearsal and practicing, and Brian is the best in the world at that.

"As for the Reef contest, that was a disaster waiting to happen. They actually wanted to bring in two-man 'teams,' like they have at their Todos Santos contest, from all over the world. That was a recipe for disaster, and we all knew it -- including Reef Brazil. And that's why they were doing it! I really believe that. They were getting a ton of publicity around a well-organized disaster. We're all glad they're out of the picture. It was like, you've already worked out who's gonna go on a surf trip, and then the most obnoxious guy on the beach suddenly jumps into the car. That's what we would have been stuck with."

MATT AMBROSE: "As long as they're respectful, and they don't take any advantage of the local scene, it doesn't bother me if they're having a contest. I'm stoked to be in it, as long as that respect is shown.

"They've really got some great international guys on that list. Gary Elkerton was like a childhood hero, the way he charged the North Shore. The world tour was one thing, but in big Hawaiian waves he was just an animal. Ross (Clarke-Jones) showed up one day last winter, and it was one of the biggest days we'd seen, and he was taking off on 20-footers, easy, all day long. So it's great. I think the place deserves a little exposure ... let people know what's really going on out there.

"I think I first surfed Maverick's in the winter of '90-91. Those early years, the swells were so clean, so far apart, and all west. It really wasn't so much the drop we were worried about, but the whole wave, just scary from beginning to end. We were on such logs, it's amazing we surfed it at all. Shaun (Rhodes) is a guy I've surfed with for years. He had a knee injury last year and pretty much missed the winter, but he's back. And he's been on it. I remember a few years back we were all riding big boards -- I had my 9-6 -- and Shaun was taking off on huge waves on an 8-2. Even Schmidt was turning his head, like, 'Whoa, what's this kid doing?' He was blowing everyone's mind.

"In my mind, Schmidt still has to be the undisputed guy. He rode that wave in '92, or whenever that was, that was bigger than anything anyone's ever gone on. Me and Shaun watched him take off. We were lucky to be a little bit inside from everybody. He just got disintegrated at the bottom of that wave. Then he paddled back out, rode another one, took it all the way past the rocks and went in."

"KEN BRADSHAW: "I've probably put in 10 sessions or so at Maverick's. I've got boards and wetsuits and a place to stay there; I'm always ready. The reason I haven't been back (since '94) is mostly logistics, but sure, after being there the day Mark died, my motivation was stifled. It just didn't seem as important to go there any more. But it's a great wave, definitely worth pursuing. My whole goal at Maverick's is to do tow-ins there on giant days when the wind's a little wrong and there are no surfers in the water. That's what I really want to do."

PETER MEL: "I'm affiliated with Quiksilver and Reef Brazil so I was kind of on the fence, but deep down, as a Maverick's surfer, I think we only need one contest. NO events would have been fine with me. At least the Quiksilver is being done right; they're keeping it small, keeping it local. Everything we ever talked about as Maverick's surfers to have an event, it's turned into that.

"You can never say a big, beautiful day is really safe at Maverick's. That Friday in '94 (when Mark Foo went down), everyone talks about how that was a small day, that the Monday and Wednesday sessions were much bigger. My observation was that it was still as big as those days, but it wasn't as consistent, so it seemed smaller. There were some 20-plus waves and the sets were 6-7 waves long, and that was crucial. If you took the first one and made a mistake, you were gonna take at least three or four big waves on the head."

JEFF CLARK: "Just to give you an idea what can happen out there, I was out one afternoon and there had been a south wind blowing all day. So it kicks up the south current, an underlying push with northwest wind-chop on top, so you might not be aware of it. I'm waiting to get a last wave in, and I get caught inside by a set. The current's pushing me in front of the waves, and this is a 20-foot set. I'm just gettin' murdered in there. And every time I come up, I can feel the current suckin' me north, so I'm just staying right in the pit. Right in the double-up section.

"This thing's just kickin' the crap out of me. By the fourth wave my leash has snapped off, so I'm swimming. The sun's already down. I'm on my back swimming, and I my heart's just red-lining; I can see it pounding right through my wetsuit. I finally made it out the channel, but it's just another one of those times, when you think you're a goner. I saw it happen to Richard Schmidt, too. He ate it at the peak, and it pushed him from the bowl all the way to Mushroom Rock before he was able to get on his board and paddle away. He endured like 10 waves. It was just hideous. I'm like, 'Oh, my God.' And this is The Man."

BROCK LITTLE: "I think this contest will be great for the sport. Anything that helps big-wave riders, and bumps up your bank account, is good for everybody, whether it's Maverick's or the Aikau or whatever. I think the younger guys need it (the publicity) more than I do. In big-wave riding, it seems you don't make a reptuation unless you do it in front of a whole bunch of cameras, or in a contest. So this will help Jay (Moriarity) and the young guys who are coming up.

"Is Maverick's different than anywhere else? In a way it is, but the way I look at it, it's just a big wave and it's freezing cold. That's the deal. Everyone knows what they're in for. I've wanted to surf it more, but for me, the priority has always been to not miss an Aikau. That's held me back a number of times. A place like Todos is pretty much guaranteed. The weather's way predictable. You can pretty much tell if it's gonna be big and offshore all day long. At Maverick's, you never know if it's gonna blow out, or be rideable for two or three hours, or just be a total writeoff when you get there that morning. That's stopped me more than anything.

"I guess the best way to really catch Maverick's is to hang around Half Moon Bay for a month or so. Well, like I've always said, I love Hawaii. I love warm water and the place where I live. I'll leave for big waves, but preferably for just 3-4 days. To station myself in Northern California and freeze my butt off for a month, that doesn't really turn me on. Especially during the Eddie Aikau time.

"I don't really buy into the whole Maverick's mystique thing. I'm gonna go ride some big waves and it's gonna be fun. And that's it. Be it Maverick's or Todos or anywhere else. Mavs is heavy, take nothing away from that. But if you go out in 20-foot surf, it's heavy everywhere, and you still have to be prepared to go out and have your butt kicked."

A California break called Maverick's turned into surfing's Super Bowl this winter, by achieving far more big-swell days than Hawaii's famed North Shore of Oahu.

``Maverick's has taken center stage for big-wave riders,'' says Evan Slater, managing editor of Surfer magazine. ``We're in a cycle where storms grow more intense after they leave Hawaii. Maverick's gets the brunt.''

On Sunday, millions of Americans lolled on sofas and watched John Elway reach his long-sought championship. At the same time, out on a lonely seascape north of Half Moon Bay, a dozen wetsuited men bobbed on their ``big gun'' longboards, ready to face an athletic test even rougher than pro football.

The surfers did not gamble for championship diamond rings or a showy trophy. Their stakes were simple and stark -- survival or death

--just to score the thrills of a lifetime.

Riveted by a need for absolute focus, they stared at the shape, rhythm, size and vector of huge swells shooting past them to burst into rocks at Pillar Point like rounds of heavy artillery. Then each one selected a ride.

Only a few score watermen have the moves and nerve to challenge a wave with the height and heft of a four-story building -- a swiftly moving structure that can demolish itself on your head. And even these men know that all their skills might not be enough to keep them from harm. Each attempt to rip a line down the face of one of these growling giants is a toss of the dice.

Maverick's is now world-famous. Its name came from the German shepherd of an old-time surfer who used to paddle out with his master to waves near the spot.

Twelve years ago, the place was an enigma. Surfers on the local shorebreak had another name for that place out past the reef where storm seas detonated, ``Mystos'' (short for ``Mysterioso''). A dim figure, rumored to have been seen riding its huge waves, was dubbed ``The Phantom.''

Yet that Phantom was real.

Jeff Clark was a Miramar local, inspired by photos of big-wave riding in Hawaii. After honing his moves on other California sites, he paddled out alone -- at age 17, in 1975 -- to face Maverick's thunder. For 15 years, Clark was the break's sole rider. Only gradually did he coax other riders to try it, surfers like Dave and Richard Schmidt, Mark (``Doc Hazard'') Renneker -- and a gangly newcomer from the East Coast named Grant Washburn.

As a kid, Washburn sketched waves on schoolbooks in the winter, then milked scant thrills on the New Jersey coast in the summer. After college, he quested westward for big surf in 1990. He thought his rainbow's end was San Francisco's Ocean Beach. But then -- encouraged by Doc Renneker to take Clark's invitation -- he discovered a further dimension.

A break like Maverick's is an inexhaustible subject. On Sunday, Washburn, 30, was devoting himself to more research.

In big surf, your take-off point is important. At Maverick's, where waves vary greatly in size and direction, it is crucial. The penalties are harsh, even fatal. In 1994, visiting Hawaiian surf star Mark Foo dropped in too far north, was caught deep in ``The Pit'' as the wave walled and got jolted off his board when an unexpected wavelet slid up the swell. Next, the ocean fell on top of him. More than an hour later, his body was found a mile away.

On Sunday, Washburn dropped late from a feathering crest and went airborne while falling down the face. Offshore winds were light, and he landed well. At many breaks, such winds bestow blessings by holding a wave up. At Maverick's, they're a curse. A gust under a board's nose may stall your drop. The result: a plunge ``over the falls'' as the crest hammers down like a ponderous fist.

As his board touched hissing seawater, Washburn sketched a steep line down the face, building speed to avoid a crest pitching out to drop tonnage in a trough 40 feet below. Moving at a withering pace, he cranked a bottom turn, driving with his right foot so hard that just 18 inches of back rail on his board stayed in the water. He scooted away from the main peak's explosion with two yards to spare.

Washburn carved right as a new section of wave began to jack up. Although chop wrinkled the wave face, he wasn't worried -- this board was built for it. The 10- foot-9-inch gun was shaped by Clark to take Washburn's 6-foot-5, 225-pound frame down a Maverick's wave. One feature is a base that ``Vee'd'' through the tail, to cut bumps and keep the board from skipping at speed.

Most surfers turned off on the wave shoulder after the main drop. Washburn wanted a second act. He coasted over a deep channel where waves briefly soften, and committed himself to the next drop. Then his wave hit a ledge and steepened, a wavelet buried the board's nose, and the curl grabbed its tail.

Washburn's dice rolled to snake eyes. Ejected from his board, he was Mixmastered in a classic Maverick's wipe-out.

Spectators may ``Ahh!'' and ``Ooh!'' over a hot ride or wild crash. But still more drama occurs below water, where Maverick's shifting currents can mug a submerged surfer. Foo had vanished into a deep bowl called ``The Cauldron.'' Driven very deep, bereft of flotation because of a broken board, Foo apparently had his board leash jam as he was shoved past a rock spur, and he was held until his air ran out.

A surfer's board and leash may be his best pal and worst enemy on the same ride. It can be the magic carpet that lets him soar away from a foaming dragon, or a frantic guillotine, chopping at him during a tumble. Or, if he's sucked deep into the cold darkness, he may need to climb his 20-foot board leash hand-over-hand to where the board floats like God's own life buoy.

As Washburn surfaced, another wave bore down. He yanked his board close to gain leash slack so he could dive. A hundred yards off, Jeff Clark cruised in a motorized Zodiac raft beyond the impact zone. Clark had surfed the best morning sets; now he was out to shoot some photos. The men locked eyes. They both knew what was about to happen.

Around Washburn's body, seawater boiled as it was sucked up into the towering mass of the next swell. He snapped Clark a brief salute

--an ironic variation on the Denver Broncos' ``Mile-High'' gesture

--and dived for the bottom.

Imagine lint in a washing machine. Washburn was tumbled hard and long. He curled into a fetal ball until the chaos faded, then surfaced with time for one breath before the next wave hit. Lungs burning, he fought upward once more and tried to breathe, but he gained only a mouthful of foam and a glimpse of a bad situation. He was being shoved toward ``The Boneyard'' of exposed reef rocks. His only hope lay in squeezing through a narrow channel.

Then he heard the whine of an outboard motor. Employing years of savvy, Clark had seen a window of low swell. He zoomed over as Washburn paddled to him. Washburn gripped a handle on the raft. Clark spun the craft around and towed him to safety. Then Washburn went straight back to the line-up to score more rides.

All Maverick's habitues know its days of solitude and secrecy are gone. With Hawaii's North Shore afflicted by swell drought, surfing magazines extol the pyrotechnics here. They've even run a photo spread of waves too big to ride. There's a Maverick's Web site and videos. Washburn, who works as a grip in the movie industry, has shot 16mm film out here since 1993. He hopes to complete a Maverick's documentary in spring.

Yet they also know this wildest ride in the North Pacific will never be jammed with too much traffic. Challengers with insufficient ability will either be scared away -- or carried away.

``Maverick's is one break that can defend itself,'' Washburn says. ``And very well, indeed.''

It wouldn't have worked anywhere else. Nobody wants to see blown-out Cloudbreak, Pipe on a north swell or 15-foot Waimea. Maverick's produced a perfectly average day for the Quiksilver/Men Who Ride Mountains contest on February 17, and the results were spectacular.

"Maverick's on an average day," said Richard Schmidt, "is pretty intense."

You knew it was real Maverick's when Grant Washburn got washed through the rocks, when Matt Ambrose broke his board on an air-drop nightmare, when locals like Ion Banner and Shawn Rhodes pulled back from the meanest-looking bombs. There was no shame. "Doesn't matter who you are," said contest director Jeff Clark. "Even when it's 15 to 18 feet, when Maverick's is pumping, you look over that edge on certain waves and you want no part of it. That just doesn't happen at other spots."

It especially seemed like Maverick's when Darryl "Flea" Virostko walked off with the $15,000 winner's check. He's been charging the place maniacally for years with an awe-inspiring combination of desire and talent. Even with stars like Schmidt, Peter Mel and Brock Little in the event, Flea's victory was proper and just, applauded by all.

Clark wore a permanent smile at the after-party that night. He'd needed the contest to run, that day, in the worst way. And if you'd been there on the beach with him 12 hours earlier, you wouldn't have given it a chance in hell.

At 8 a.m., the usual kick-off time for major events, the whole place was enveloped in fog. The buoy readings suggested that there were 20-foot sets out there and that they would last all day, but who could tell? There was a four-hour wait until the break became visible through the mist. And even then, a peaking high tide had rendered it weak and inconsistent.

Clark, who is to Maverick's what George Downing is to the Eddie Aikau contest, made the "go" call anyway. He trusted the buoy readings and his knowledge that Maverick's jacks when the tide goes out. Most of all, he didn't want to disappoint his Hawaiian visitors, who had already experienced one false-alarm trip to Half Moon Bay.

It's one thing if Mel or Kelly Slater gets lost in the Eddie whirlwind, making a half-dozen futile trips in a month. The Eddie happens on its own good time. But it doesn't work in reverse. Maverick's still has some proving to do, and Clark had an all-star cast in town: Little, Ken Bradshaw, judges Bernie Baker and Jack Shipley, Ocean Safety lifeguards Mel Pu'u, Victor Lopez, Dennis Gouveia and Craig Davidson. He also had all 20 entrants ready to go--not a single alternate needed.

The format had already been changed from advance-and-elimination, featuring semifinal and final heats, to an Aikau-style event: everyone surfs two heats, then we'll add up the scores. But by the time the fog lifted and the contest got underway, it was already past noon, which meant there would be time for each competitor to surf only once. Fortunately, the five-man heats were extended to an hour, giving everyone a chance to go off--and everyone did. All of the local stars showed exactly why they earned their Maverick's reputations. For instance, some had questioned the inclusion of Mark Renneker, saying his surfing ability didn't match the rest of the field, but Renneker rode three waves expertly and finished 12th--incredibly, ahead of Evan Slater, Ambrose, Rhodes, Washburn and Bradshaw.

"I'm sure he won't let us forget that, either," joked Bradshaw.

As if by magic, Maverick's came to life as soon as the first heat hit the water. Little set the tone, catching four solid waves and thoroughly dominating the heat. Mel was hindered by an aggravated knee injury, which had kept him out of the water for a week, and he surfed with a thick brace on his front leg. That had to be an annoying handicap for Maverick's main man, but he surfed well enough to impress the judges. To the surprise of nearly everyone, Mel finished fourth and Little seventh.

Brock didn't seem the slightest bit angry, but, then, nothing much bothers him. Not 25-foot Waimea, not the fact that it was his first Maverick's session since Mark Foo died, not even Jaws, where he pulled into a massive and totally unmakeable tube the first time he rode the place. "It's cool," Little said of the Maverick's judging. "You get burned sometimes, but it usually comes back around in your favour. I'm glad Peter got fourth. I liked being here."

The second heat began with Rhodes, a rock-solid veteran of many Maverick's seasons, surfing a booming set wave with style and precision. Unfortunately, it didn't count. The heat hadn't officially started. That seemed to deflate Rhodes, who was pretty quiet for the rest of the heat, and Santa Cruz surfer Zach Wormhoudt took over.

When you think about it, Santa Cruz has produced more great big-wave surfers than any city, town or community outside Hawaii. There's Schmidt, Mel and Virostko. There's Jay Moriarity and Josh Loya, who finished fifth and sixth in the contest, respectively. There are old hands Vince Collier and Anthony Ruffo, and fearless underlings like Mike Brumett, Neil Matthies and Kenny "Skindog" Collins. And then there are the Wormhoudt brothers, Zach and Jake, with their low-key assault on every big swell.

Zach had a dazzling heat, first surviving a behind-the-peak takeoff by bulling his way through a mountain of whitewater. Then he pulled into a massive inside-section barrel, and although he didn't make it, the mere effort was insane. A few moments later, there was a fascinating juxtaposition of chaos: the sight of Washburn heading straight for the rocks, using his local knowledge to shoot the gap on his board, while Loya pulled into a hideous beast--successfully--outside.

"It took me forever to get back out there," said Washburn, "but at that point, I didn't even care. It was just so cool to see this contest going off, with some truly dangerous set waves and everybody charging it. That's what this day was all about. I don't think anybody was that wrapped up in the scores."

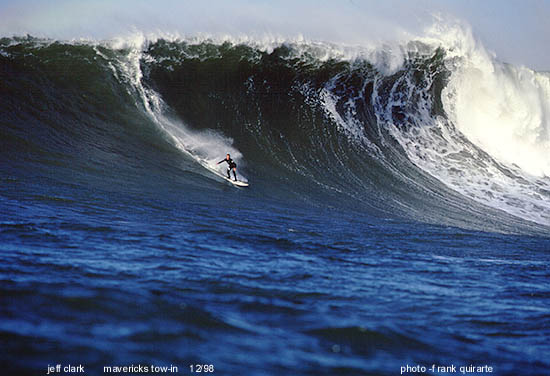

By the third heat, it was vintage Maverick's. Not the perfect, blue-sky morning with ideal light and photographers dotting the channel, but late afternoon, backlit, with a wicked northwest wind, waves rudely sucking out in the retreating tide and just a handful of surfers in the water, barely visible from land. That's how it goes down here, day after challenging day in the winter. And that was the stage for Virostko and Ross Clarke-Jones in the day's best heat.

With cliffside viewers squinting through the glare, Virostko and Clarke-Jones put on an unbelievable show on consecutive 20-foot waves. Both pulled their air-drops, both came screaming off the bottom and both negotiated a gaping inside section, Flea actually making it out of a top-third barrel (a feat later matched by Tony Ray). People were going crazy; Virostko scored a 98, top score of the day, and Clarke-Jones had the signature piece of his third-place finish. "That had to be the coolest thing that went down all day, those two waves," said Washburn.

It was left to Schmidt, still an absolute master at age 38, to apply the finishing touches. With two high-performance rides, he made a late rush in the day's final heat to finish second behind Virostko. But it was his phenomenal top turn earlier--basically a layback on an inside face that had to be 20 feet--that bent minds. It was Schmidt in full flight, cranking the kind of move you just don't see at Maverick's.

"Did he do that layback intentionally?" someone wondered. "No question about it," said Little, who was standing nearby. "Richard will tell you it wasn't, 'cause he's so modest, but that's what he does."

Before his heat, Schmidt was one of the few competitors who watched the contest from the bluffs--a smart move, as it turned out. Out on Wild Wave, the 65-foot boat that served as headquarters for judges and competitors, it was the Hurl Invitational, as many of the players spent the afternoon spitting up their breakfast over the side.

The crew from Esquire magazine, sources said, was quite the disgrace. They made a big show of forcing their way onto the boat, throwing their weight around as heavyweight journalists, and within a couple of hours, they wanted out. "There were fully clothed guys bailing on Jet Skis--anything to get out of there," said alternate Steve Dwyer. "They were actually offering money for a ride. 'I got a hundred bucks--take me in.' All the guys on the boat were just laughing at 'em."

Vince Collier, of course, was the main heckler. This was a great day for Collier, who got to surf in the event and saw some of his protégés, particularly Virostko, go out and kill it. For years, Collier was the guy waking up the Santa Cruz wannabes, cranking up the radio, pouring the coffee and steaming up the coast with a car full of stoke.

And the day of the contest, Collier, Flea and company were in rare form. They pulled up at 5:30 in the morning, with heavy-metal music booming, amped out of their minds. Alternate John Raymond, who has surfed the place maybe 50 times this season, remembers the scene: "They were just screaming. 'Yeah! F---in' right on!' I see 'em here all the time, but at that hour, I'm thinking, who are these guys?"

To top it off, Flea had added a special touch to his platinum-dyed hair, dotting it with black spots. A couple of surfers were calling him "the Dennis Rodman of surfing," but there was much more to the story. Flea wound up winning this contest with tragedy swirling all around him.

He had dedicated that hairstyle to his good friend Skye Ksander, manager of the HotLine surf team, who is undergoing chemotherapy for cancer. "The guy's going to be losing his hair," said Flea. "So I messed up my hair in honor of him. If he looks fried, why shouldn't I?"

As if that wasn't enough to think about, moments before Flea stepped up to receive his winner's trophy, he learned that his good friend Pat Groen, a 22-year-old Santa Cruz surfing buddy, had died of a brain aneurysm, completely without warning. No wonder he looked a little shell-shocked as the night went on.

"It was so weird coming from such a high, getting congratulated by people I respect and grew up watching, to finding out my friend died," he said. "It's just bullshit. Stuff like that just isn't fair."

By the time Virostko got around to celebrating--and rest assured that he partied hard with his friends that night--he was absorbing the best part of that day: his vindication as a big-wave surfer.

"I've kind of been the dark horse all year," he said. "Peter [Mel] has gotten all the attention, and that's cool, but I always surfed Maverick's for pleasure, and he was the one the cameras followed around. That bugged me a little. But now I think things have turned around for me."

Flea is part of that exclusive crowd--names like Mel and Rusty Keaulana come quickly to mind--that can lay claim as one of the most versatile surfers in the world. It's a pretty tough hang: you have to be off-the-scale good in 3-foot waves and a true standout at 25 feet. That's why so many people celebrated Flea's win at Maverick's: his time had come.

"[Flea] deserves it more than anyone," said Schmidt. "This is a guy who does aerial 360s on small waves, then takes that same high standard into big Maverick's. He's out there taking air-drop wipeouts, being swept onto the rocks, nearly drowning a couple of times and going right back out, unfazed. That needed to be recognized. Peter Mel's got the recognition, but Flea hadn't achieved that. This really sealed his reputation."

Maverick's didn't fare too badly, either. They need a ban on helicopters for next year ("I felt like the FBI was after me," said one competitor), and they might consider posting the judges on the cliff, where the seasickness factor disappears and a full Maverick's ride can be witnessed, but otherwise, the event was a success.

Pu'u and Gouveia, a couple of Makaha-side heroes who thought they'd seen it all, went back to Hawaii with a whole new outlook on the surfing world. "You go out there [on a Jet Ski] and you're reduced to nothing," said Gouveia. "First, I can't hear 'cause of my helmet. Then there's the fog, so now I can't see. Pretty soon it's so cold; I can't feel anything. I'm losing all my senses." "You're senseless," said Pu'u, and they both cracked up. But Pu'u kept saying the same thing, all night long, as the post-contest party raged on. "To surf waves like that in water that cold," he said, "Those are real men."

In the end, it wasn't so much about classic conditions or memorable rides at the Maverick's surf contest yesterday. It was more about the big-wave surf culture, so nobly represented at the remote spot near Half Moon Bay, and the environment, carefully preserved for future use.

Despite some angry words, there were no major incidents regarding the strict security that turned away the general public. Despite weather conditions that threatened to force a postponement, there wasn't a single no- show among the 20 invitees. And when the Quiksilver/Men Who Ride Mountains event was over, Darryl (Flea) Virostko, one of Maverick's most talented and courageous locals, won first prize and walked off with $15,000.

The day belonged to Santa Cruz, a town that has produced more big-wave surfers than any other community outside Hawaii in the past 10 years. Virostko and second-place finisher Richard Schmidt are Santa Cruz mainstays, along with Peter Mel (fourth place), Josh Loya (fifth) and Jay Moriarity (sixth). Ross Clarke-Jones of Australia finished third, and Hawaii's Brock Little took seventh.

After more than two months of waiting for the perfect day, contest officials were determined to hold the event yesterday. Noting that a major swell was rolling down from the Pacific Northwest, they alerted everyone concerned -- including a crew of surfers, judges and ocean-safety lifeguards who arrived Tuesday from Hawaii.

"We already had one false-alarm alert, and another one would have been pretty discouraging," said contest director Jeff Clark, the Half Moon Bay surfer who pioneered Maverick's in the mid-'70s. "So we were gonna go this time, even if it wasn't perfect."

It was far from that. A factor no one had counted upon -- heavy fog -- shut down the event until noon. That forced a change of format, limiting the contest to four one-hour heats with five surfers apiece. By the time the sun appeared in late afternoon, a heavy northwest wind was up. It wasn't a day for blue-green water, postcard-perfect photographs or dancing girls on the beach. It was Northern California in essence: cold, challenging and forbidding.

The waves were in the 15- to 18-foot range, with the occasional 20- footer and long lulls between sets. On the wildest, heaviest days at Maverick's, 25-foot surf is the norm. But no one was complaining yesterday. Not after watching an all-star cast in full assault, raising the Maverick's performance level to new standards.

"It was just a great thing to see everybody here, enjoying themselves and getting great waves," said San Francisco entrant Grant Washburn. "I didn't have the greatest heat, but I didn't even care. It was more about doing justice to Maverick's as one of the best waves in the world, and we did that. The caliber of surfing was tremendous."

Tube rides, usually reserved for the small-wave arena, were almost commonplace yesterday. Virostko, Australia's Tony Ray and yet another Santa Cruz surfer, Zach Wormhoudt, all had the distinction of pulling into a giant Maverick's barrel. Who rode the biggest wave? The honor seemed to switch hands all day. Matt Ambrose, Shawn Rhodes, Loya, Washburn, Clarke-Jones, Virostko and Schmidt were all major players on that score.

Maverick's has such fascinating waves -- and such a relatively new discovery, having only become popular this decade -- everyone wants to see it. Yesterday, that became a problem, because only a few people were allowed to see it.

The only remotely good viewing point is along the high cliffs at the edge of the Pillar Point Air Force Station. But it's a narrow, precarious (and, yesterday, quite soggy) space, with a sheer drop of some 200 feet to the rocks below. The notion of an overflow crowd yesterday was intolerable for Air Force officials, the San Mateo Harbor Commission and local police.

``One kid falls over that cliff, or one dog, and it's all over,'' said one contest official. ``The area could be made entirely off-limits, and the Quiksilver contest would probably not be welcomed back.''

Several hundred people made the long walk from Princeton to the beach yesterday (traffic access was completely blocked). A few of them stationed themselves on the short, steep slope leading to the cliffs. Others scaled the cliff side to give themselves 40 to 50 feet of elevation. But only a handful of media representatives were allowed onto the cliff top itself. And that didn't sit to well with spectators used to frequenting that area.

``Fortunately, there were no arrests or disturbances, no problems with alcohol or anything like that,'' said Sheriff Gary Johnson of the San Mateo County. ``A few people didn't understand the security, and they got a little angry with us. But overall it went very well. Probably better than we expected.''

(1) As waves near the shallow water of the coast, they slow down and bunch together.

(2) Wave length gets shorter, so wave height increases. Waves are caused by action of the wind blowing across the surface of the sea. Their size depends on:

-- Wind speed

-- Distance traveled

-- Duration

(3) ``The Boneyard''

Due to the unusual contour of the sea floor at Mavericks, where the bottom suddenly rises from 66 to 21 feet deep, the waves here are much steeper.

MEN WHO ARE WAITING TO RIDE MOUNTAINS

They've got plenty of time. Contest director Jeff Clark and Quiksilver officials have a waiting period lasting until Jan. 27 to run the Men Who Ride Mountains contest at Maverick's. In the meantime, the spot has seen giant surf, jet-ski breakthroughs and what might be its greatest day of surfing since the spot became popular in the early '90s.

No wonder Clark had a big smile on his face on the night of Dec. 12, when local surfers and photographers gathered for a slides-and-video show near the Princeton Harbor. This has already been a memorable winter, and there appears to be no letup in sight.

A chronology of a remarkable three weeks:

Monday, Nov. 23: The Hawaiian Ocean Safety contingent arrives. Brian Keaulana and Terry Ahue, two lifeguarding legends scheduled to work emergency rescue for the contest, walked the cliffs above Maverick's with George Downing, coordinator of the Eddie Aikau contest at Waimea Bay. Ken Bradshaw also flew over, eager to experience his first Maverick's session in four years.

It was a wild, huge, stormy day, blown to hell by south winds. There really wasn't much to see beyond the general layout and the stark reality of a Northern California winter. "I can't believe anyone goes into water this cold," said Ahue, bundled up against the wind. "I also can't believe guys surf in front of those frickin' rocks."

The plan is for Keaulana, Ahue, Dennis Gouveia, Mel Pu'u, Archie Kalepa and Craig Davidson to fly over from Hawaii, with each man provided with a jet-ski craft for the contest. Additional rescue help will come from Frank Quirarte, head of the Maverick's Water Patrol, and Shawn Alladio, a highly skilled woman who has performed a number of military jet-ski missions and worked the Reef Brazil contest at 25-foot Todos Santos last February.

Unfortunately, the Hawaiians had a tight schedule and had to leave at the crack of dawn the following morning. Bradshaw stayed around, but the lifeguards never got in the water. That's a shame, because they really missed something.

Tuesday, Nov. 24: It's mind-blowing huge, some say the biggest Maverick's they've ever seen, and as usual, the bombs aren't being ridden. Not from the peak, anyway. Even Bradshaw made that concession as he watched in awe from the shoulder.

"So, Ken, how big do you think it is?" Grant Washburn asked as they paddled over a monstrous wave. Off to the side, John Raymond and Mark Renneker were trying not to laugh. Bradshaw is notorious for his skepticism on the size of Northern California waves.

"I'd say 25 feet, easy," said Bradshaw, to the delight of everyone.

"OK," Washburn thought to himself. "We really DO have big surf here."

He always knew it, but it didn't hurt to get some validation from Bradshaw, who last winter got towed into the largest wave ever ridden on Oahu.

Washburn blew everyone away that day -- even Bradshaw, who had his mind on tow-in surfing and wasn't that comfortable paddling in on his 10-6.

"It was the biggest Maverick's I've ever seen, and Grant was just on it," said Bradshaw. "He was even more impressive than Peter Mel that day, because he caught the biggest waves. Grant really hangs in there. He's bouncing all over the place on this one wave, and I completely wrote him off, but he made it. Peter's more beautiful to watch, but Grant is really going big."

Raymond, who has made countless trips to Maverick's with Washburn, said, "Grant really stepped up. He definitely out-surfed everybody, no question about it. There was one wave near the end of the day, when it was just Kenny, myself, Shawn Rhodes, Matt Ambrose and Grant out there. This huge set came through and Kenny was yelling for me to go. I started paddling in when I saw Grant about 30 yards deeper, just turning around and launching into this thing. Right into the pit on a really big wave. Bradshaw was floored. He was like, 'Whoa!' And Grant made that wave. He pretty much made all of 'em."

Washburn wasn't ready to call it the biggest day he'd seen. "To me, there were a couple of days last winter that were bigger," he said. "But it was the same kind of deal: Waves breaking way out to the north on the outer reef. It was unreal, because we had a 15-foot, 14-second windswell breaking on top of 23 feet, 17 seconds, and there were just waves breaking everywhere, all the time. I saw four guys head out from the beach and four of 'em were turned back."

To even begin to grasp Washburn's mindset, imagine heading out alone at stormy, 12-15-foot Ocean Beach some lonely afternoon. That's what Washburn did on Monday, the day before. "Waves were breaking way out on the patch," he said. "Nobody on the beach or in the water. I went out there and managed to get two huge lefts. Really satisfying."

On days like Tuesday at Maverick's, there are no surprises. You've heard the names before. "Jay Moriarity was killin' it," said Quirarte. "Kenny (Collins) is really turning it on. And Moose (Neil Matthies, who had a horrific two-wave hold-down last January) is really charging it this year."

"I think Jay got the bomb of the winter that day," said Renneker. "There was a wave behind it, and he made it. Really impressive. But overall, I'd say Grant's the man this year. When all of us are paddling to get over a big set wave or heading for the channel, you're aware that Grant is actually paddling to get in position to take off. And then he goes. Even if the penalty would be huge. And he's not falling. So far (laughter)."

Bradshaw wanted badly to tow in that day, especially when the winds became severe in the afternoon, but his partner, Dan Moore, was back on Oahu and Jeff Clark was getting some major dental work. Instead, Bradshaw grabbed Quirarte's jet-ski and put on a show, basically scouring the Maverick's playing field with a combination of raw courage and extreme skill.

"He went everywhere you could possibly go," said Washburn. "He was bombing through the pit on the biggest sets. He went through the lefts. He went all around and through the rocks. Everybody was impressed, even Shawn, who's really got her thing wired, too. The difference there is Ken's experience in big waves. She was out there blazin' around, but at one point, she said to me, 'That last wave was the biggest I've seen in my life.'

"Ken was taking some chances, no doubt about it," said Washburn, "but he's much more qualified than anybody around here. He's so comfortable out there. He was totally playing around."

Quirarte had the perfect attitude, standing his ground as the local ace but watching Bradshaw's every move. "Ken is the man, for sure," he said. "He just gave us the whole lowdown. Seeing the master, that was a great thing for all of us. Everybody just sat back and applauded."

Bradshaw said he couldn't believe that Ahue, Keaulana and Downing had to get back to Hawaii so soon. "They missed seeing a 25-foot day," he said. "But I think I accomplished a lot that day. I learned more about Maverick's than I had in the 10 previous times I'd been out there. My point was to show the confidence you can get with the machine once you know how to operate it correctly. Before, people were saying you couldn't do any rescues around the rocks. I think I shattered some misconceptions about not being able to go in there."

Preparing for the session at the harbor that morning, it dawned on Bradshaw: This was his last, horrible memory of Maverick's from the last time he visited it: Dec. 23, 1994, watching paramedics throw a blanket over Mark Foo's dead body.

"Just then I realized it had been three years, 11 months almost to the day. Doc (Renneker) showed up to get a ride out to the lineup, and I said to him, 'Doc, this is interesting. This is perfect. The last time here, I ended my session at the harbor. Now I'm gonna start my session at the harbor (as opposed to the beach, where paddle-in surfers hit the water). There's sort of an irony in that. And I liked it that way. I did all of that for Mark. It kind of helped me through the whole experience."

Thursday, Nov. 26: Perhaps the wave of the future: Surfers in the morning, when conditions were relatively clean, and tow-ins in the blown-out afternoon. This was another giant day, with sets of at least 25 feet, and the morning belonged to Darryl (Flea) Virostko.

"It was the Flea show," said photographer Doug Acton, yet another Maverick's jet-ski operator. "He came, he conquered, he went. Everyone else kind of played catch-up."

Raymond said Flea got out there early, "and he caught like 10 waves, just a psycho thing. So he was steppin' up, too. Flea, Peter and Grant, those are the three kings."

Very few serious waves were ridden that day, but with surfers in the lineup, Bradshaw and Jeff Clark motored over to Blackhand Reef for some tow-ins there. "Peter Mel's got a ski now, and he came over to watch, and Grant got sort of curious and he hopped a ride on Frank's ski," said Bradshaw. "It was probably four times overhead over there -- not that big, but fast and thick, a great place to practice. Finally there were just two guys left at Maverick's, and when we got over there they said, 'Cool, go ahead and tow in. We'd like to check that out.'"

Bradshaw and Clark towing each other into Maverick's? Who wouldn't want to watch that? And again, Bradshaw was struck by a moment of historical significance.

"I said to Jeff, 'This is so appropriate. Get your board. I'm going to tow you first. You started this whole thing (surfing at Maverick's, way back in the mid-70s), so you should do the first tow-in.'"

To be accurate, it had been done before -- by Clark, on a smaller scale, and by the Santa Cruz team of Perry Miller and Doug Hansen last winter. In fact,one of Miller's rides -- documented by a wire-service photo -- is widely considered to be the biggest wave ever ridden at Maverick's. But Clark and some other Maverick's locals have a bias against Miller and Hansen, because they haven't paid their dues. As they readily admit, they are tow-in specialists. They've never paddled into a Maverick's wave, and as Bradshaw says, "I don't think you're fully legitimate if you do that. Tow-in surfing should be a reward for years of paddle-in surfing in giant waves, and you bring all the experience you've gained from that."

For big-league, big-name action, the Bradshaw-Clark collaboration was a Maverick's first. Mel got towed into a couple, as well, turning loose his magic with some gorgeous S-turns before the waves started to break. The highlight had to be Bradshaw's attempt to "backdoor" a massive set wave, coming from behind the peak and trying to sneak underneath the lip.

"I jumped this wake, hit the face, and tried to turn across real quick," said Bradshaw. "I mean, I was full-on backdooring it. I thought I could stick it through. Didn't work. It just blew up, and I got clobbered."

What was the pounding like?

"It was good (laughter)," said Bradshaw. "A real good pounding. It was just lights out. I thought, wow, that was a big hit."

Before long, in the good-natured ribbing of Maverick's camaraderie, Bradshaw was being portrayed as the messenger of evil. "I was like the crack cocaine dealer invading the schoolyard with all these innocent kids," he said, laughing. 'Come on, all you kids, who wants to try it? First time's free.'"

But for Mel and Bradshaw, two cutting-edge Maverick's surfers, it wasn't 100 percent funny. They face a maddening dilemma with tow-in surfing, and the arguments rage within their minds. "I think it almost scared Peter, how great and fun and easy it is," said Washburn. "This is a guy who wants to win that Quiksilver contest here. He told me if he does too many tow-ins, he'll lose his touch with paddle-in surfing."

"But wait until the contest is over," said Acton. "After that, the genie's gonna be let out. Pete's so capable. A lot of these guys are. They were meant to do it."

Washburn may be among the last to commit. "The takeoff part is so simple, it removes the main challenge of surfing big waves," he said. "Hey, I completely believe that Ken Bradshaw could ride a 30-footer from the outside; come all the way across the peak and make it. Other guys could do it, too. But I like the traditional game. Maverick's is such a neat place for catching a wave on your own power. Kenny says it's archaic. Well, it is -- and it isn't. I told him, don't forget what you did for all those years, just turn and face the beast. That whole symbolic thing of man's struggle against nature. That's why I'm in the game. I love the hunt and thrill."

Bradshaw's tow-in act drew quite a crowd, and most of them were spellbound. "I saw Ken take off on this mutant wave, just dropping and dropping to the bottom forever," said Acton. "Like he was in slow motion. Oh, my God ... it was just a whole new world. It was so fun to see him do that. He's truly an inspiration. Other guys sort of scoff about Maverick's and never come surf the place, but Kenny, he's all over it. And he's 46 years old! He's just a true waterman from the word go."

Clark will have major input on the future of tow-in surfing at Maverick's, and he sees the same pattern continuing: Paddle-surfing as long as the waves are clean, tow-ins for the late afternoon if the lineup is empty.

"I don't think tow-ins will ever dominate here," said Clark. "They shouldn't; Maverick's is the ultiamte pure surf spot. It's not like Waimea, where it closes out on huge swells. Not like Todos, where waves start breaking all over the ocean. Maverick's holds any swell, they all break on one bowl or the other, and they can be surfed.

"Don't get me wrong, I like tow-ins a lot," he said. "Oh, yeah. You can really get sucked into this tow-in game. But the two do not go together in any way, shape or form. And that's the way it should be."

Here's how Bradshaw described his side of it:

"Those two big days, Tuesday and Thursday, were typical of the big swells you see out there. Guys looking at 25-foot waves from the shoulder and just drooling. Nobody's sitting on the peak and nobody WILL be. The face of that wave literally scallops right out of the swell. It has more velocity, more heave, than Waimea or any other paddle-in spot. Even when people take off on the shoulder at Maverick's, they can barely breach that velocity of pitch -- you see how much it lifts 'em up and it's all they can do to get down that thing. When people look the pictures, they wonder why guys have so much difficulty taking off at the peak. Well, the pictures don't truly show how it is in real life. You know that insane, heaving spot they call The Box in Australia? Where it just surges over a shallow reef? Maverick's is like a giant Box. That was much more clear to me this time than ever before. Paddle-surfing, I was watching waves peel off outside of where I was sitting, and I didn't move. Better judgment told me not to."

Bradshaw recalled the sight of Mel on the three or four tow-in rides he got: "He's such a beautiful surfer to watch, and even more so when he does a bunch of turns and then makes his drop IN the bowl. All of a sudden, the break is approachable. You CAN go over there. You may have a big advantage on the takeoff, but once you get onto that face, man, you're surfing."

Renneker, the San Francisco physician, watched all of this in amusement. He's good friends with Bradshaw, a friendship that can withstand any surfing debate, but he represents the flip side of the tow-in argument. It should be noted that there was uproarious laughter through much of Mark's rant. It's not like he wants Bradshaw to leave Northern California forever. But this was Renneker's reaction to what he saw during Thanksgiving week:

"It was interesting to watch Ken, because he just blew doughnuts on what anybody's ever done on jet-skis here. It was astonishing to watch. After about five minutes of that, it was like, Ken, will you go away?

"I mean, that day he was just puttering around solo out there, it was just ridiculous. The outer peak starts to break, like 25 feet, and he's right next to you, talking, aboard this Yamaha something-or-other. Then, in a nanosecond, he does this big brodie turn, sprays water all over the place, races in front of the wave, does a 180-degree turn and goes back out on the left. It's almost like he was laughing at us. It was appalling.

"From the safety angle, I have to say he was impressive. He took all the guys, put 'em in the pit and came in to make simulated rescues. He was masterful. You really have to listen to what he says, because it looks like he's going to kill you. He does that elbow-to-elbow thing, where you hook yours onto his as he races by, and I mean, this is 20 miles an hour straight AT you. I was ready to dive underwater and take my chances elsewhere. But then, away you go. Incredible safety measure. It's obvious he's a hell of a driver.

"But while we're doing all this, I'm getting nausea from the fumes. I'm hating it. And there's jet-skis everywhere. If we could vote tomorrow to ban those things, except for safety-rescue and photographic purposes, I think we would all vote now to ban 'em.

"I'm not there on the get-into-the-wave early argument," Renneker went on. "Not me. If that's the case, just fly me onto that mountain, drop me right above the Hillary step, I'll hike up that last hundred feet, and by God, I've climbed Everest! And by the way, I have a new machine where I don't actually have to do the climbing. Just strap myself in, push a button and it climbs for me.

"I just think it's a desecration to the degree that there's some bad juju around the corner. These things do not belong there. And then to watch 'em all reveling in their greatness afterward -- you know, like they were jet pilots who flew around the world, and man, we flew really fast. Compare that with Magellan getting together with Cabrillo, talking about fucking sailing around the world. I mean, THAT's real.

"I see nothing wrong with a surf spot so powerful, so magnificent, that you can't ride all of the waves. I don't find it all beautiful that someone can insert himself on it, with gas and oil and silicone belching. Can't you see the beauty of a gorgeous mountain that can't be climbed at a certain point? That's what makes Everest. And when the storm's on it, those are the days to sit back and respect it, be in awe of it, not go out and pound it into submission.

"It's the worst. Jet-skis are like the biggest, most godawful mosquitoes you've ever been around. They just don't shut up. And here comes the guy being towed, looking just like a water skier. Big deal. Let's all get the brewskis and go hang at the lake."

This, clearly, is an argument to be continued.

Friday, Dec. 11: It was history. It was all of the elements coming together. It was the epic swell of '94 all over again, with one big difference: The surfing was incredible. If you combine weather, water texture, size and performance, Dec. 11 might have been the greatest surfing day in Maverick's history.

As the slide-video show unfolded the following night, the images came back to life: Incredible stills by Quirarte and Don Montgomery. Insane video by the newly formed combination of Eric Nelson (High Noon at Low Tide, Twenty Feet Under) and Curt Myers (Heavy Water, Half Moon Bay). It was 18-20 feet, with bigger sets, blue-green water, mild temperatures and slight offshores, and everyone said the same thing: "This was the day. We could have held the contest."

Fortunately, for the sake of eliminating those second thoughts, there was one quirk: The waves were slow to arrive. Contests are usually called at around 7 a.m., and in the lull of this Friday morning, they wouldn't have pulled the trigger. Even if they had, two or three morning heats would have been skunked.

So it was left to the locals, just as it was in December 1994. If you've seen those videos, you remember guys just falling off the cliff, one after another, taking the worst cold-water wipeouts you'd seen in your life. Now, with four years of experience and improved equipment, guys are just killing it. There were some ferocious wipeouts, to be sure, but the caliber of surfing reached an especially high level.

"It was just epic out there," said Shawn Rhodes, who joined Matt Ambrose, Kenny Collins, Peter Mel, Steve Dwyer, Evan Slater and Jay Moriarity as the standouts of the day.

Strangely, a lot of regulars were missing: The Wormhoudt brothers, Flea Virostko, Steve Lowery, Vince Collier. But the action was pulsating. Mel pulled into a full-on barrel, and while he didn't make it out, the mere attempt was tremendous. Slater caught some bombs and took a horrendous mid-face fall on a wave well over 20 feet. And Dwyer was particularly amazing, making some unbelievable drops and at one point being tossed over the falls as he was caught inside, just a few feet short of being able to push through. At 37, with a wife, famiily and responsible job as an educator, Dwyer recently talked of "pulling back" at Maverick's, saying he just couldn't charge with his old flair and commitment.

"Yeah, but that was before I saw the conditions on Friday," he said. "It was so perfect, there was no question about it. Ambrose and Rhodes were the men of the day. They're smart out there and they have the four most important elements in surfing: power, speed, positioning and style. Many guys have three of those attributes; few have all four."

The next month will bring some riveting Maverick's photos in the surfing magazines. At season's end, look for the best videos yet. And before too long, the contest will go off. Maverick's looks ready for the occasion.

FIRST-ROUND HEAT SETUP FOR CONTEST DAY

ONE

Brock Little

Peter Mel

Matt Ambrose

Ion Banner

Vince Collier

TWO

Ken Bradshaw

Grant Washburn

Josh Loya

Shawn Rhodes

Zach Wormhoudt

THREE

Darryl Virostko

Jay Moriarity

Ross Clarke-Jones

Jake Wormhoudt

Mark Renneker

FOUR

Richard Schmidt

Evan Slater

Don Curry

Tony Ray

Steve Lowery

DECEMBER 19TH 1995 - BIG SWELL AT MAVS

The mention of December 19th brings chilling memories for the strong-willed surfers of Northern California. It was on that morning that a week of epic, historic surf began at Maverick's last winter. This year, as if on cue, the 19th brought the first combination of big waves and clean conditions to the notorious spot near Half Moon Bay.

It was a sunny, beautiful morning, and the usual crew of Santa Cruz dawn patrollers -- including Flea Virostko, Josh Loya and Anthony Ruffo -- showed up right on schedule. The waves were a clean 15 feet, with occasional bigger sets, and by 8 a.m. there were 19 guys in the water. By the end of the day, such Maverick's regulars as Grant Washburn, Donald Curry, Darin Bingham, Mark Renneker, Matt Ambrose, Steve Dwyer, John Raymond, Christy Davis and the most respected of them all, Mavericks innovator Jeff Clark, had enjoyed their share of waves.

Historical reference: Last December 19 was the morning of fierce offshores, unbelievable wipeouts and waves pushing 25 feet. That's the morning 16-year-old Jay Moriarty took his well-documented wipeout, believed by many to be the worst they'd ever seen outside of Hawaii. Two days later came Big Wednesday, another day of 25-foot sets and heroic deeds, a day that seemed to have been filmed by every notable surf videographer on the planet. And on Friday of that week, the 23rd, Mark Foo met his death at Maverick's. Locals still get the chills when they remember the sequence: First, the sudden arrival of a tropical, multi-colored cloud formation above the break. Then the set that ended Foo's life -- and nearly those of big-wave legends Brock Little and Mike Parsons. Then the evaporation of those clouds, just as quickly as they appeared, and a rush of contrary onshore winds. And finally a jarring rainstorm that shut down not only the day, but the entire winter at Maverick's.