| ||||||

| Articles | Projects | Resume | Cartoons | Windsurfing | Paintings | Album |

The Conflict Between Killer Whales and Commercial Fishing Operators in British Columbia: Legislative Solutions

by

Waterose

There is a cartoon on the way for this one!

Here it is!

Adopt a Killer Whale!

The legislation to protect killer whales, Orcinus orca, in British Columbia is ineffective. The conflict between killer whales and commercial fishing vessel operators in British Columbia is an example of the inadequacies of the legislation to protect killer whales.

This paper examines the historical development of attempts to use legislation to protect killer whales in the area of Johnstone Strait, British Columbia. The major legislative instruments include the National Parks Act, S.C., 1988, c. 48; the Ecological Reserve Act, R.S.B.C., 1979, c.101; the Fisheries Act, R.S.C.,1985, c.F-14; the Marine Mammal Regulations, SOR/93-56; and the Oceans Act S.C. 1996, c.31. The Oceans Act, formerly Bill C-36, came into force on January 31, 1997. The Oceans Act has the potential to be effective legislation to protect the killer whales in British Columbia.

The killer whale is a marine mammal. Marine mammals are protected under the Fisheries Act. Under this act "fish" includes shellfish, crustaceans and marine animals. The Fisheries Act Regulations include regulation of commercial fishing and the management of whales. Section 7 of the Marine Mammal Regulations prohibit the disturbance of marine mammals except when fishing for marine mammals.

There are three distinct races of killer whales that frequent the coastal waters of British Columbia; the offshores, the transients and the residents (Ford 16). The races are distinguished by their dialect and their diet (ibid 18). The offshores are seldom observed in the coastal waters of B.C. (ibid). The transients feed primarily on marine mammals(ibid). The residents, the most frequently observed B.C. killer whales in Johnstone Strait, feed on salmon (ibid). The killer whales usually arrive in Johnstone Strait at the same time as the migrating salmon which are returning to the spawning streams (ibid). The resident killer whale population feed in Johnstone Strait from mid June to late fall when the salmon have completed the spawning runs (ibid).

Commercial fishermen and killer whales compete for the same natural resource - salmon. Traditionally, killer whales have been not been harvested by commercial fishermen because the whales are too small to be of commercial value. Rather, the whales have been treated as a nuisance to commercial fishing operations. In the 1960's the Federal Department of Fisheries condoned the culling of killer whales by killing them with firearms:

"It is recommended that one .50 calibre machine gun with tripod mounting be used [at Seymour Narrows] with ball ammunition only...If the whales approach from the westward, method of attack would be to open fire when they approach" (Johnstone-Background Report I).

The importance of killer whales came to the attention of the public with the increasing number of performing killer whales in captivity. With increased public attention, the scientific community focused more attention on studying killer whales in their natural habitat.

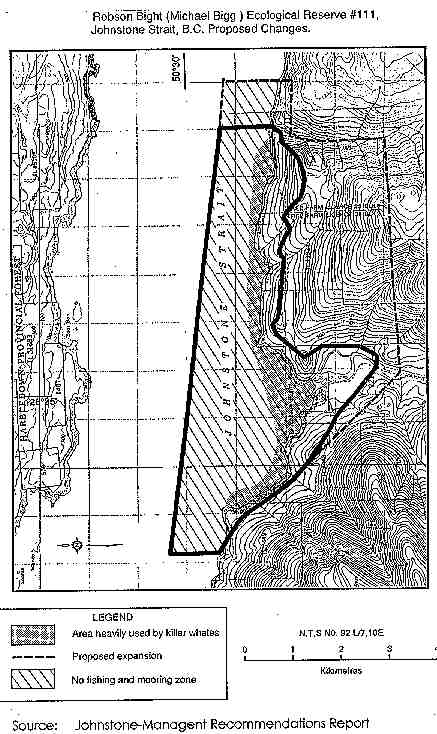

The most important area for studying killer whales in their natural habitat is Johnstone Straight located near the northeast end of Vancouver Island. Of particular interest is the area of the Robson Bight Michael Bigg Ecological Reserve (RBMBER)(please see Appendix I-location map).

RBMBER is a unique area of habitat because it has shallow pebble beaches that the whales visit daily to engage in the activity of beach rubbing (Ford 35). RBMBER was initially established as a site of national significance in 1982 by Parks Canada to protect approximately nine kilometres of shoreline (Johnstone-Background Report 1) under the National Parks Act S. 9 (1)(b). The RBMBER was subsequently expanded to include a land buffer zone in 1988 by the B.C. Ministry of Parks (ibid). The RBMBER currently includes 1248 hectares of marine area and 505 hectares of land buffer zone. The use of the area is heavily restricted and access to the RBMBER is restricted to authorised permit holders under the authority of the B.C. Ecological Reserves Act.

The B.C. Ministry of Parks and the Federal Department of Fisheries and Oceans work co-operatively to develop management options to ensure the continued presence of killer whales in the Johnstone Strait area (Johnstone-Background Report ii). Extensive studies culminated in the formation of the Johnstone Strait Killer Whale Committee which conducts ongoing studies to develop management strategies.

The management plans are concerned with issues regarding the disturbance of the killer whales in their natural habitat. Disturbances to killer whales include commercial fishing operations, sports fishing activities, logging operations, and commercial whale watching activities.

The activities of the commercial fishermen over marine waters are regulated by the Fisheries Act. The establishment and management of the RBMBER is regulated by the B.C. Ecological Reserves Act. Under this act, the provincial authorities can regulate and enforce inland activities on crown land at the RBMBER. The patrol of water activities is administered by the provincial authorities and requests voluntary co-operation from vessels in the area. There are no definitive regulations to enforce compliance in the waters off the Robson Bight beach area. The legal question arises with respect to the attempts to control the activities of the commercial fishing operators which are exempt from the provincial regulations and restrictions enforced in the ecological reserve area. The activities of the commercial fishing operations and the natural behaviour of the whales are inevitably in conflict.

The reason that the conflict exists is because both the commercial fishing operators and the killer whales compete for the same natural resource at the same time of year. Commercial harvesting of salmon is heavily regulated due to the reduction in salmon stocks. The nature of the conflict between commercial fishing operations and killer whales is not limited to competing for the same natural resource.

The conflict is exacerbated by the behaviour of the commercial fishing operators within the RBMBER.

"The Reserve is also used by commercial salmon fishermen to set their nets, to tie their nets to shore and to moor their boats. Between [fishing] openings, fishermen are often out in skiffs visiting other boats, target-shooting, fishing, watching for signs of fish accumulation, whale watching or exploring the land" (Johnstone-Background Report 50).

The commercial fishing vessels form the majority of the vessels in the area during the period that the whales are present (Impact 11). The fishing vessels are present twenty four hours a day, four to seven days a week(ibid). They fish within ten to fifty meters from shore and directly above rubbing beaches (ibid). One of the most disturbing aspects of commercial fishing operator behaviour is the continued use of firearms in the reserve area. "Gunfire was heard on 35% of the days that commercial fishing vessels were moored" (ibid). In addition, there is periodic use of explosives known as seal bombs in the beaches area (ibid). The presence of commercial fishing operators in Johnstone Strait engaged in the activities described is a threat and a danger to the use of this habitat by killer whales.

The protection of the killer whales is provided for under Section 7 of the Marine Mammal Regulations. The regulations prohibit the chasing, shooting or harassing of whales. The regulations are not enforced unless there is evidence of potential physical harm to the whales because there is not a legal definition of harassment (Johnstone-Background Report 46). In 1984 there was an unsuccessful attempt by the crown to prosecute a commercial fisherman for shooting firearms at whales (ibid). This is unfortunate because this case had the potential to set a precedent for the definition of the term 'harassment to whales' (ibid). In a more recent case, R. v. Richards (1991) BC Pr.Ct (unreported) Judges Bracken & Doherty [Judge Bracken presided over the court hearings August 22-23,1991, Judge Doherty issued the decision October 1, 1991.per Port Hardy Court Registry, File 7290.] the crown was also unsuccessful in obtaining a conviction for harassment to whales in the RBMBER under the Marine Mammal Regulations (Lochbaum, Ford). The Marine Mammal Regulations have subsequently been revised (P.C. 1993-189, 4 February), but the revisions neither provide for additional protection to marine mammals nor provide a definition of harassment.

The commercial fishing operators in Johnstone Strait and in the area of the RBMBER are the "largest single source of disturbance to the whales, primarily at the rubbing beaches" (Johnstone-Background Report 69). Both the whales and the commercial fishing operators compete for the salmon resource in the same area during the same time period. The issue at hand is not only an issue of legal jurisdiction between the provincial authorities and the rights of the commercial fishing operators in the area of RBMBER. The issue is the dichotomy between the rights of the killer whales and the rights of the commercial fishing operators. In principle, both can coexist providing that the salmon resource continues to exist. The depletion of the salmon stocks increases the competition between the commercial fishing operators and the killer whales. If the commercial fishing operators perceive that the killer whales are depriving the operators of an adequate share of the salmon resource, then it is inevitable that the harassment will increase. The potential exists for the commercial fishing operators to attempt to reduce the numbers of killer whales that compete for the salmon resource.

The existing legislation is inadequate to protect the killer whales under present salmon stock conditions. There have been proposed options to "reduce the number of whale disturbances from minimal reduction in disturbances to maximum reduction in disturbances. A maximum reduction in disturbances means prohibiting fishing in the reserve area" Johnstone-Background Report 60). One of the major shortcomings of the proposed recommendations is the failure to take into account the present state of the salmon population and the trend in reduction of salmon population. This omission fails to recognise the inevitable increase in competition between killer whales and commercial fishing operators for the salmon resource and the potential consequent actions. The proposed changes in management by the committee suggests that improved legislation is required to protect killer whales and their habitat. It is dubious as to whether or not the implementation of amendments to the Fisheries Act and the B.C. Ecological Reserves Act would be sufficient to be effective because of the application of the respective jurisdictions of the provincial and the federal statutes under the Constitution Act, 1867, R.S.B.C. 1979, c.62.

The Constitution Act divides the provincial and federal jurisdictions under sections 91 and 92. Section 91 establishes the management of fisheries under the federal jurisdiction. Section 92 establishes the management of crown land under the provincial jurisdiction. The Fisheries Act provides for the regulation of the commercial fishing operators and the protection to whales from harassment outside the ecological reserve. The B.C. Ecological Reserves Act provides for the operation and management of the RBMBER and applies to the reserve inland and over the sea bed. Both the provincial and the federal authorities are working co-operatively to satisfy the needs of both the killer whales and the commercial salmon fishing industry.

The review of the situation at Johnstone Strait has been ongoing since the 1970's. The primary objective of the governments and the members of the interested committees is to develop legislation that is both effective and enforceable. The Oceans Act is the most significant Canadian environmental legislation to be enacted that can potentially protect marine animals from harassment of any kind.

The Oceans Act provides for the establishment of Marine Protected Areas (MPA) that are defined in section 35 :

"A marine protected area is an area of sea that forms part of the internal waters of Canada, the territorial sea of Canada or the exclusive economic zone of Canada; and has been designated under this section for special protection for one or more of the following purposes: (a) conservation and protection of commercial and non-commercial fisheries resources, including marine mammals and their habitats;"

The Oceans Act provides for joint administration between the federal and the provincial government for enforcement of any regulations that may be applied to a designated MPA. It is the opinion of Paul MacKinnon, Marine Biologist, Department of Fisheries and Oceans that the Oceans Act will be the most effective legislation to provide protection to marine animals (MacKinnon). MacKinnon advises that each MPA will have a specific set of regulations to meet the needs of each MPA. It will be possible to stipulate that commercial fishermen do not approach to within a specified distance, the boundaries of the ecological reserve (MacKinnon).

The regulations with respect to the ecological reserve remain standing under the B.C. Ecological Reserves Act, thus the inland regions and the sea bed regions remain protected. The difference will be the flexibility in co-ordinating partnership administration and enforcement of both the MPA regulations and the ecological reserve regulations.

The implementation of the Oceans Act will be a lengthy process. The government plans to implement a systematic approach. The priority will be to consider applications for MPA's in areas that are adjacent to existing ecological reserves and marine parks (Marine).

It is anticipated that the marine area adjacent to the RBMBER could be designated a MPA within two years (MacKinnon). Mr. Ed Lochbaum, Co-Chairperson of the Johnstone Strait Killer Whale Committee views the Oceans Act and the establishment of an MPA in the Johnstone Strait region as an effective positive step to provide adequate legislative protection to the killer whales from any further harassment (Lochbaum).

The issue of developing adequate legislation to protect killer whales in British Columbia may be solved with the implementation of the regulations developed under the Oceans Act. The conflict between killer whales and commercial fishing vessel operators in British Columbia is not resolved. The killer whales and the commercial salmon fishing industry continue to compete for the same dwindling resource and consequently are in conflict; the solution is dichotomous.

Postscript 2000

Almost five years later I can revisit this paper and advise that the Canadian Federal Government, Department of Fisheries and Oceans appears to be moving forward to establish Marine Protected Areas through a stepped process. The initial phase is to establish a Pilot Project which can then become a model MPA. Once such example is the extraordinary Race Rocks Pilot Project. More information is available at the new Race Rocks Marine Protected Area Website. I invite you to browse their site for more information and updates. I can only wish that Robson Bight will one day become an MPA as well. Whales are to BC as Mountain Gorillas are to the Congo.

Appendix 1: Map of Johnstone Strait

Bibliography

Ford, John K.B. Killer Whales. UBC Press, Vancouver, B.C. 1994.

Ford, John K.B. Johnstone Strait Killer Whale Committee. Vancouver Public Aquarium. Personal telephone interview. 10 April. 1997.

Impact on Killer Whales, March 1991. Province of British Columbia, Ministry of Parks. 1991.

Johnstone Strait Killer Whale Committee Background Report, 1991. Province of British Columbia, B.C. Parks. Fisheries and Oceans.1991.

Johnstone Strait Killer Whale Committee Public Response Summary. Province of British Columbia, B.C. Parks. Fisheries and Oceans.1991.

Johnstone Strait Killer Whale Committee Management Recommendations. Province of British Columbia, B.C.Parks. Fisheries and Oceans. 1992.

Killer Whales and Coastal Log Management; An Overview of the Future Uses of Robson Bight. Province of B.C. Ministry of Environment. 1981.

Lochbaum, Ed. Co-Chair, Johnstone Strait Killer Whale Committee. Department of Fisheries and Oceans. Personal telephone interview. 11 April. 1997.

MacKinnon, Paul. Department of Fisheries & Oceans. Personal telephone interview. 11 April. 1997.

"Marine Protected Areas under the Oceans Act". Department of Fisheries and Oceans. 1997. On-line. Internet. Available: Ocean Act Discussion Paper

Rennie, Francis. An Assessment of the National Significance of Robson Bight British Columbia. National Parks Branch. Parks Canada. 1982.

email Waterose

email Waterose

Please Sign My Guestbook

Please View My Guestbook

| Articles | Projects | Resume | Cartoons | Windsurfing | Paintings | Album |

| ||||||