The Ghost

of the Ulu Batang Ai

(Published in 1992)

The Ghost |

| "So how did you like the Batang Ai", I asked. "Pretty interesting area. Hey, I have been hearing a lot about you up there. You seem to have quite a reputation among the longhouse people," my colleague said, chuckling. Up till then, it had been a simple telephone conversation, between two colleagues discussing a future project into the interior of Sarawak. But that loud chuckle made wonder which of several stories about me he had heard? "Oh, they were telling me about the ghost you saw", he said, reassuringly. I couldn't stop laughing as I told him what had happened. The Ulu Batang Ai is a series of small but never-ending hills connected by spiny ridges. Between them, even smaller valleys, with rivulets, streams and rivers frothing and twisting through these natural obstructions. |

For over four centuries, the area had been under shifting cultivation by Ibans from longhouses even farther upstream. Being close to the Kalimantan border, they had became vulnerable to Indonesian attack during the confrontation. As a result, people from the more remote longhouses were evacuated to Lubok Antu in 1963.

| Further dislocations followed twenty years later when the Batang Ai Hydroelectric Dam created a huge artificial lake with a surface area of about 8500 hectares, or 33 square miles. The water level had risen nearly sixty metres above the original river level, inundating 26 longhouses. |  |

And hundreds of Ibans moved out to resettlement schemes around Lubok Antu. The area, about 250 km from Kuching, was gazetted as the Batang Ai National Park in 1991, and Mike Meredith had been called in to prepare a Management Plan for the Park.

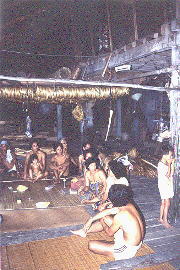

| He and his small team of Ibans were conducting a series of faunal surveys in the area, and I was asked to make an inventory of its birds, as a result of which I found myself in a camp on the banks of the Sungei Lubang Baya. Eight feet down a steep slope lay our two boats, pulled high onto a pebble beach. Directly in front, the Sungei Akup, forty feet wide at this point and ankle-deep with silt-laden water, trickled over a sand bank into the Lubang Baya. Our little beach, or kerangan as the Ibans called it, some ten feet wide and thirty long, was one of the few campsites along that dangerous and fast-flowing river. |

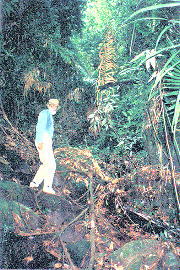

I had to sample bird populations from two sites, each with a different vegetation type. I set out immediately after setting up our camp. Wading half a mile up the Akup, we found a hill slope covered with kerangas forests, its pole-like trees less than ten metres tall due to poor soil conditions. It was an almost vertical climb, and treacherous underfoot with fallen leaves and other debris. Almost doubled up and gasping for breath, I reached the top of the ridge. It was a perfect site for birding with a wonderful view of the adjoining hills and valleys.

| Within half an hour, with the help of the Ibans, I had cut clearings in between some trees to make space for my mist-nets. This camp was going to be a piece of cake, I thought, feeling rather pleased with life at that juncture. Wading down the Akup to its junction with the Lubang Baya, I turned right and marched off into the jungle again, to a patch of old secondary forest I had seen earlier, smack bang in front of our camp itself. The trail was easy at first, until it was blocked by debris left behind by a previous flood. Once over that, we were faced by another of Ai's hills, inevitably, a steep one. |   |

Both Nyanggau and Kaya seemed reluctant to go any further. Probably wanted to head back to camp and rest, I thought, looking at my watch. It was only three in the afternoon, time enough to cut the rides for the next set of nets. I scrambled up the hill, and was relieved to find another perfect site. The Ibans seemed less enthusiastic. They pointed out that, to reach this site, I would have to wade across the river daily, up to my chest in water. They insisted that there was a better site, on the same side of the river as our camp. Adamant, I pushed on, marking out the rides as I went along.

| At the third ride, I noticed a few ceramic jars on the ground. Nyanggau told me that the Ibans used to keep padi in such jars long ago. Not exactly a lie but most certainly not the whole truth either. I kept quiet for those were old Iban funeral jars whose presence worried me. |

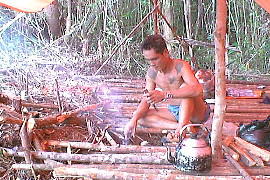

The tense situation eased somewhat when it began to rain a little later. We dashed back to camp. Rimong and Angai were busy putting our makeshift kitchen in order. A few minutes later, the rain stopped and the young Ibans suggested that I look at the site they had suggested earlier.

| The trail began immediately behind our camp, steeply up a ridge for about four hundred metres to a level patch covered by low spindly vegetation. The netting site lay a further three hundred metres away, along another steep ridge. It was clearly an impossible site, and I went back to camp, the others trailing behind to gather material for the camp. Back in camp, a wood fire was merrily crackling away and a kettle, thoroughly blackened with soot, emitted clouds of steam. After a cup of coffee, the Ibans began preparing dinner, a collective effort. One person saw to the rice and opened up a tin of curried chicken, another chopped up some fish, put it into a strip of bamboo and propped it up by the fire to cook, all the while engaged in casual cross-talk. They dealt with all manner of things - of trips to various other parts of the country and abroad, the things they saw or did while there, the people they met and so on. The more hilarious tales were, inevitably, of their hunting expeditions, some that had gone hopelessly awry, others that had been hugely successful. |   |

This continued throughout dinner and right up to the time we headed for our respective bunks, ready for sleep. Once in my tent, I kept thinking about a notable omission in that conversation. At no time had they discussed the jars we saw up on that hill. I dismissed the thought. Shortly afterwards, I thought I heard someone call me and called out to ask who it was. Then, realising that is was just Rimong, coughing, I switched off the torch and went to sleep.

| I was woken at three in the morning. Kaya, in a bunk just beside my tent, was having some sort of nightmare and was talking in his sleep. Someone else - later discovered to be Nyanggau - was trying to comfort him. Neither of these events seemed significant enough for me to take note of - at that time. Nor did the Ibans mention them the next morning, not that there was much time for any kind of small talk that early in the morning. Up by five-thirty, breakfast was a frugal and hurried affair of cream crackers - the Ibans call it roti - dipped in coffee or milo. At first light, around six, we dispersed. I crossed the river and went up the hill to set up my nets, the Ibans going further up the Akup, to clear a faunal survey site. The netting site proved its worth and kept me busy all morning. Around noon, while watching birds, something crashed through the undergrowth some hundred yards beyond my nets. |

Hoping it was a wild animal, I scanned the area with binoculars and saw a man walking through tall bracken fern and down the hill, only his back and blue T-shirt showing at times. At first, I thought it was one of our Ibans, then realised it was not - the man was walking away from me, and the camp. Back in camp that evening, I asked the others if they had seen anyone else in the jungle that day. They looked puzzled and discussed the matter thoroughly amongst themselves. Then, after asking a few questions, they suggested I must have been mistaken, that I had probably seen some animal. I scornfully dismissed the notion, saying that I had yet to meet animals that wore T-shirts, blue or otherwise. And set off for the river to bathe.

| There was a full moon that night, and dinner was rather more subdued than usual. Which suited me fine - after twelve hours in the jungle, I was quite tired and went to sleep early. I was awakened by a loud scream from Kaya who was having another one of his nightmares. Nyanggau went to his aid again with words of reassurance. It was therefore quite a relief when the young Ibans left for Lubok Antu the following morning, to fetch Mike who had been away for a meeting. Rimong left with them, for a short visit to his own longhouse - about a kilometre away - and was back in camp by the time I returned from work. |  |

That night, after dinner, Rimong and I had a long and frank conversation. He had asked around at his longhouse and was now certain that none of his people had been in the area - had I really seen a person walking down the hill, not just an animal? I gave him several reasons why I felt sure it was a man. In turn, I wanted a straight answer to a question - was the hill pantang (a taboo area)? He assured me it was not, just that they avoided the hill since it was known to be haunted.

| What if I worked in the burial ground but avoided the jars themselves, would that offend them or pose any other problem? No, he said, then opened up and talked freely. He asked me about that night when I had called out to someone who had come to my tent. And laughed when I told him of the mistake I had made after hearing him cough. |

He told me about Kaya's nightmares. During our first night there, after our visit to the burial ground, Kaya had gone down to the river to answer a call of nature. There, he had seen a very bright light shining just above the hill, like a giant eye. Certain that it was some kind of ghost or Hantu, he had run back to his bunk shivering with fright. And this had prompted his subsequent nightmares. The nightly conversations became a ritual between us. The matter was discussed many times over the following two weeks but the man in the blue T-shirt kept cropping up. And while Rimong accepted my statements at face value, I could never convince him that I had made no mistake, that it was a living human being I had seen, not a ghost. And I slowly began to understand just how the deep-rooted his belief in supernatural beings was.

Oriental Dwarf Kingfisher |

| The Kelabit Connection | Footloose In Sarawak | Pun Ritai's Home Page |

© Pun Ritai (Updated on 21st April 1998)