(Published in 1985)

(Published in 1985) |

| The world is never really seen at its best at half past five in the morning. Night was almost over and it was not quite morning as I stood at the prow of an 18-metre express boat at Kapit, the administrative headquarters of Sarawak's Seventh Division. The far bank of the Batang Rejang was an indistinct blur, the tall trees on the far side only just visible, like the sails of ghostly ships shrouded in a morning mist. Overhead, three hornbills honked their way across the river, black silhouettes, their large wings flapping loudly in the morning quiet. A few metres away, a floating fuel station gleamed in the half-light. All was silence until the express boat's 350 horse-power diesel engine started up. At the entrance of the boat, an elderly woman leant against the bulkhead, fast asleep, clutching one of the metal stanchions for security. Beside her, a dead sambar deer, its fur matted and blood-stained around its middle. Despite the early hour, the boat was packed. It was on its way to Sibu, 130 kilometres downriver. People and their baggage were everywhere, inside the boat, outside the cabin, on the bench seat at the stern and even on the roof amidst a cargo of large cardboard cartons tied up with pink plastic raffia. |

In a State where there are very few roads, rivers such as these are the arteries of life and industry in the interior. At Kapit, nearly 260 kilometres from the sea, the Rejang is over sixty metres wide and thirty metres deep. With a roar, the Flying Swallow started down the river. It had a specially designed steel-plated hull to protect the boat from floating logs and debris. As the morning grew, the river began to reveal some of its secrets. A logging camp or two, the occasional longhouse and a sawmill.

| Slowly, the river awoke. A power boat, all blue and white, roared past us, throbbing purposefully out of sight, a long frothing trail of white in its wake. Caught in this turbulence, a tiny dugout rocked precariously as it hugged the safe waters along the river bank. On the muddy shores, below a longhouse, a group of young women, bare-breasted and bathing at the river's edge, modestly turned their backs on us as we passed. Nearby, a group of young children happily wallowed and played, knee-deep in mud, their shrills of delight audible even above the roar of our diesel engines. On a hill overlooking the river, a modern wooden building stood proud against the horizon, its white-painted walls catching the early morning light. |   |

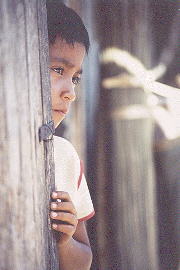

The boatman called out - I had arrived at my destination and the building was a school. The forty-minute journey had cost me five Ringgit. The Flying Swallow slowed down, inched forwards to deposit me neatly at the longhouse jetty and pulled out once again, back into the river within seconds. I carefully negotiated the narrow rickety ramp from the jetty onto the upper bank, a slow ten-metre climb. Background laughter told me that I was under observation. At the top, a group of children awaited me, highly amused by my hesitant progress up the ramp.

| Behind them, an open padang, many more children playing football in front of smaller school buildings. I offered a few of them some sweets but, though quite friendly, they kept their distance. A shy smile or two greeted my attempts, polite refusal nonetheless. Some thirty away, two women peered hesitantly at me behind the safety of a clump of bushes. As I walked towards them, they bolted up a ramp that led into the longhouse. The children broke into open laughter. A man strode out of the longhouse, past the women, towards me . Jeffrey anak Jawa, aged 32, could have stepped out of any city street, so well dressed was he. The Tuai Rumah, Nalung anak Daga, being the Penghulu (Headman) of the area as well, was away attending a Council meeting at Kapit. So Jeffrey, his assistant, welcomed me to his longhouse. He spoke fairly good English. One should never enter a longhouse unless invited. The invitation was immediate. After a brief exchange of greetings and an almost formal exchange of names, we took off our shoes and entered the long enclosed verandah, or ruai. |

The longhouse was built some three metres above ground on stilts made of thick pieces of timber. From outside, the building gave an impression of a long wall pierced by several doorways along its length. As I came through this door, I was confronted by a long enclosed verandah and yet another wall. This too had a series of doors along its length, each one leading into a bilek or room, each room housing a family. The number of doors on this inner wall indicated how many families resided there. Nanga Ibau was a forty-door longhouse.

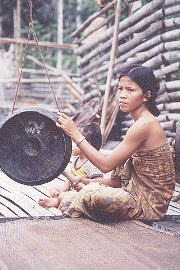

| The interior of the longhouse verandah was spartan. And fairly dim inside. A long wooden bench was aligned against the wall. In front of it, a linoleum mat. Jeffrey placed a woven mat upon it and invited me to sit down. A few of the doors along the far wall were open, women peering out to see who had come. Any visitor to a longhouse is the personal guest of whoever invites him there. In my case, Jeffrey was my host and would be responsible for me as long as I stayed there. Paying for my food and lodging was out of the question. As a way out, I gave my host a present of several tins of canned food and a couple of packets of sweets for the children of the village. Ideally, I should have given the sweets directly to the children. They were, however, exceedingly shy. Shortly after we were seated, other members of the longhouse began to gather around us, most of them women. The older ones sat beside us on the mat, the younger women being clustered around the doorways, slowly coming closer as curiosity got the better of them. |   |

"I don't see any of your men here", I said. We were conversing in a vile mixture of Malay, Iban and English. "Gone to the farms", Jeffrey replied. Apparently, the men leave at six every morning to work on the collective farms across the river. When they returned, usually well after dark, they would bring back whatever food or jungle produce they were able to find during the course of a long working day.

| Farming was still by the shifting cultivation method. An area is cleared and the rubble burnt. In August, the main crop of padi is planted. After the harvest, a secondary crop of ubi kayu or tapioca is taken before the land is allowed to revert to nature. Nanga Ibau was not one of the really old traditional longhouses - concessions had been made to time. They had an electric generator and piped water though they still did their cooking using firewood. The interior doors were custom-made ones fitted with glass louvre panels. Above each door was a hunting trophy, the skulls of various kinds of deer, mainly sambar. At one time, the trophy would have been a human skull, that of an enemy killed in battle. |

The Ibans have surrendered some of their more colourful customs. An elderly lady came up to me, smiling, bearing a very young baby in her arms. Two others lined up behind her. Kneeling in front of me, the first one very ceremoniously handed me the child. The fragile two-month old stared up at me, its enormous dark eyes fascinated by my beard. As for me, embarrassed sort of sums it up. Everyone was looking at me, obviously in high humour. I was terrified that I might drop the baby.

| After the third child had been handed to me and retrieved, it occurred to me that there had to be a reason for all this. I asked Jeffrey. From what I could gather, since children of that age were unable to leave the longhouse and see the world in person, contact with a visitor from the outside enabled them to go out, by proxy so to speak. |  |

There was a major problem developing for me, the matter of taking photographs. No hostility or resentment, just a great reluctance to be photographed. Each time I picked up my camera, they giggled and retreated, only to return smiling as soon as I put it away. Eventually, they "persuaded" a group of children to pose for me - en masse! Not really the sort of photograph I would like to have taken but I dutifully complied. Honour was saved on both sides.

| Jeffrey invited me to his bilek or room. The interior was decorated with clippings from various magazines, an assortment of woven hats, mats and bags, not to mention a truly wonderful collection of old Chinese urns that lined one side of the room. After a simple meal of rice with fish curry and pork, washed down with coffee made from home-grown beans, he took me on a short tour of the village. Different points in the village were linked up by a series of footpaths that straggled through the jungle. Across a wide gully, they had erected a simple but very stable wooden bridge. Jeffrey was quite worried about their small pepper crop. "Too many insects. The yield is very low, so also the price of pepper." He pointed towards a new clearing. "Now we grow cocoa". Their cocoa crop, planted three years ago, was just beginning to fruit. It should bring in a fair income when mature. The main problem seems to be one of income and employment. Traditional methods and lifestyles are no longer applicable. To maintain a decent standard of living, many young men and women have left the village in search of work. |

To Kapit, to Sibu, Brunei, Sabah, and even to Saudi Arabia. Sixty young men have gone. Jeffrey himself works as a tractor driver in a logging camp near Belaga, a full day away by boat. On average, he stays in the village for only four days in a month. Others are less fortunate. They send money home to support their families but come home only once every year or so. The problem is accentuated by education. The school at Nanga Ibau caters for the children from all the neighbouring longhouses, a total of 168 pupils, both boys and girls.

| It gives basic schooling in Bahasa Malaysia up to Standard Six. All education is free - the children need only to pay for their exercise books. And there are dormitory facilities for the children from the other longhouses. Schooling is not compulsory at any level. Those who wish to go to Form One or further need to become boarders at schools in Kapit or Kuching. Several schools in the area serve as channels to these secondary schools. Beyond Form Five, the students have to go further afield. Currently there are only fifty children from Kapit undergoing education at Form Six level. |

Sadly, though, education is a gateway that leads away from the community, not one that directly benefits it. It renders the villager unemployable in the village or its immediate vicinity. In the absence of any real job opportunities, educated Ibans will be forced to move away from their ancestral homes. The local school's only graduate, a student from Nanga Buan, now lives and works in Kuala Lumpur. As I boarded the express boat an hour later on my way back to Kapit, I could not help but wonder how much longer the longhouse culture could survive. A lot of pressure is coming to bear on their traditions and cultural values.

| Footloose In Sarawak | Pun Ritai's Home Page | The Kelabit Connection |

© Pun Ritai

(Updated on 21st April 1998)