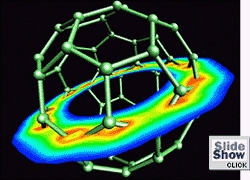

This "buckyball" is one of the great hopes of nanotechnology. To scientists, this clump of carbon atoms is a major building block in reproducing natural processes. Click for more molecular images. (ABCNEWS.com)

By

Chris Stamper

ABCNEWS.com

Imagine surgical tools that can fight disease at a molecular level.

Imagine computers smaller than a human cell and microscopic, superefficient

manufacturing tools that cut pollution.

Those are the goals of nanotechnology, the

futuristic hybrid science that will one day blend engineering and chemistry

to build products at the molecular — or even atomic — level.

Currently, organizations from IBM and Lucent

to the National Science Foundation and NASA are investigating the possibilities

of nanotechnology. The science is mostly experimental, carried out with

computer models and high-powered microscopes. So far, the practical results

have included microscopic electronic components called micromachined electromechanical

systems. Their most common use is in car air bag sensors.

Ralph Merkle, a researcher at Xerox’s Palo

Alto research facility, compares nanotechnology in 1998 to aviation in

the late 19th century. The revolution in manipulating materials too small

to see is right around the next scientific bend.

“Nature has given us Lego blocks and we can’t

move them the way we want,” Merkle says. “It’s like we have boxing gloves

on.”

Out of Thin Air

Nanotechnology’s primary goal is reproducing natural processes. If trees

can make wood without a factory, Merkle and his colleagues argue, people

can produce strong materials using efficient, small-scale molecular “machines.”

Diamonds, for example, could in theory be made by rearranging carbon atoms.

The problem is fashioning microtools that can push atoms around with precision.

To make ever-smaller components, researchers

are developing minuscule building blocks called buckyballs and nanotubes.

Buckyballs are named for the visionary architect/engineer

R. Buckminister Fuller, the designer of the geodesic dome. Infinitesimal

soccer ball-shaped clumps of 60 carbon atoms, they could be used to make

everything from plastics to batteries. Stretched out into nanotubes, they

are 100 times stronger than steel, yet six times lighter. Nanotechnology

researchers envision nanotubes as the connectors and cables in future miniaturized

electronics.

“You can use them as TinkerToys to build things

with, like little strings,” explains Donald Noid, a senior scientist at

the Department of Energy’s Oak Ridge National Laboratory .

Nanotechnologists imagine a day when these

carbon building blocks can be used to make diamonds cheap and plentiful.

Later on, they hope to build tiny devices that can be used to build other,

larger devices.

“The ultimate fantasy is to have a machine

the size of a sugar cube that has a solar panel that sucks carbon dioxide

out of the air, strips the oxygen away and starts building,” Jim Von Her,

president of Zybex, a small nanotechnology startup in Richardson, Texas.

“I can imagine a house made out of air and sunlight.”

If that sounds preposterous, listen to Bill

Spence, editor of NanoTechnology Magazine in Honolulu. Not only does he

predict micromanufacturing sites in private homes, where people build their

own wristwatches and computers as easily as they’d print out this article;

Spence suggests that nanotechnology could lead to immortality, once tiny

devices can start tinkering with a human’s genetic and cellular structure.

Not So Fast

Manual labor — all manual labor, including surgery — could become obsolete,

according to these theories.

“What happens when you can get a box that

looks like a microwave oven where atoms can go in one side and consumer

products go out the other?” Spence asks. “There won’t be any more autoworkers.

There will be just auto designers.”

Poppycock, says Charles Joslin, editor of

“Nanotech Alert,” a newsletter produced by John Wiley & Sons, an Englewood,

N.J.-based technology publisher. “People talk about a million tiny robots

in your house designing a free refrigerator; that’s nonsense.”

Nevertheless, governments around the world

are already pumping around $430 million annually into nanotech research.

Nanotechnology may not re-engineer human existence, but over the next few

decades it may well yield electronic components that could revolutionize

manufacturing processes.

And that’s no small thing.