.

|

|

Boron

fire,

tidier than hydrocarbons',

abler,

is less easily lit.

Hydrogen, in principle still lighter,

ignites very easily ...

Boron: A Better Energy Carrier than Hydrogen?

... while with boron the easy part is the handling.

If drivers send slabs of (even less ignitable!)

boria

across the Earth,

and get back boron,

both forms' manageability helps

this energy tap be efficient.

But no cars seem to use it yet.

Cars that did, being safer,

could bring a motorist-chosen End of Oil.

Global nuclear/solar plugin cachet

might help.

|

Click image for table of contents

This work is Copyright © 1999-2001 Graham R.L. Cowan,

and may not be reproduced by any means for material or financial gain

without his written permission.

Encouragement by John McCarthy (Progress and Its Sustainability)

is gratefully acknowledged.

These people link to it,

as all are welcome to do, without notice,

or, if they wish to be considered for the list, with.

This work is Copyright © 1999-2001 Graham R.L. Cowan,

and may not be reproduced by any means for material or financial gain

without his written permission.

Encouragement by John McCarthy (Progress and Its Sustainability)

is gratefully acknowledged.

These people link to it,

as all are welcome to do, without notice,

or, if they wish to be considered for the list, with.

Linking Pages

Linking Pages

Here are some web sites that have recently linked to this one:

WebConX

"Sustainable Home Built Energy Production"

As long as boron energy transfer isn't yet letting a householder

tap at will into clean energy sources half the world away,

in preference to dirty ones nearby,

why not harvest clean energy in the back yard.

Hydrogen Energy Center

"working to demonstrate the potential of hydrogen"

REB Research & Consulting

"specializes in hydrogen separations and membrane reactors."

Hydrogen flows through metals, some very much more than others.

MIT Solar Electric Vehicle Team

"Winners of the 1999 World Solar Challenge, Cut-Out Class"

Indirect solar drive via faraway boron-deoxidizing

solar power stations is one possibility.

But a solar electricity plant right on the car

is a real engineering tour de force.

Chemdex Odds and Ends

"Chemdex is the directory of chemistry on the World-Wide Web"

This is its Miscellaneous section.

Introduction

Introduction

|

|

|

|

|

Boron fibre photo courtesy Textron Systems.

Future cars may have fuel spools not fuel tanks.

|

|

|

|

|

Boron is a hard refractory material a little like diamond.

Both it and carbon are chemical elements.

They are neighbours in the periodic table:

boron is the fifth element,

carbon the sixth .

Both are used as reinforcing fibre in composites.

.

Both are used as reinforcing fibre in composites.

The case for boron as fuel begins with a safety advantage.

Although very combustible, it also is very hard to light.

Spools of boron fibre like those shown could not be lit

even if a loose end were attacked with a blowtorch.

Not in air.

Risk reduction through the use of this fuel that won't burn can be realized

if combustors provide an unearthly environment where it will:

pure oxygen, high pressure.

Hard though this may be, it will yield other benefits

(cf. Why Boron Motors Won't Emit).

|

|

|

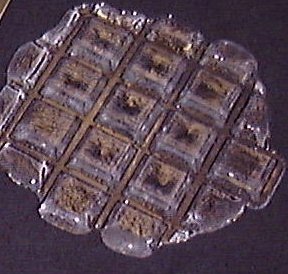

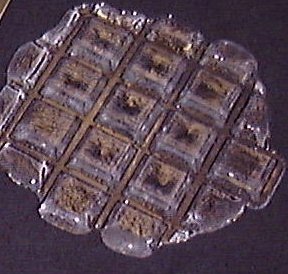

Syrupy when poured at 500-plus Celsius,

this transparent boron oxide (enlarge) has since

frozen rock-hard.

Photo courtesy RASA Industries

|

|

|

|

|

Return Ashes to Sender

That is the plan for boron.

In a four-mile, sub-four-minute dash

a hydrocarbon car might produce 1.43 kg of carbon dioxide.

That's most of a cubic metre,

enough to make many cubic metres of air unbreathable.

But if it could be reduced in volume a thousandfold,

and made to cohere in a lump that wouldn't stale any air,

it might begin to resemble the equivalent shown here:

1.25 kg of boria .

.

This 184 mm piece of glass is near in size and mass to an Olympic women's discus.

In a pinch it could serve as one, on a grass field.

If thrown onto a less yielding surface it would break .

.

Ash in boron cars would start out as similarly lustrous, transparent ingots.

They wouldn't be thrown anywhere, rather,

they would go back to nuclear or solar power plants to be de-burnt.

Boron Decombustion

proposes a thermal method.

The boron would be sent forth to be fuel again .

.

Not Just Safety

Ignition resistance in a fuel is a good thing.

Traditional fuels' lack of it has figured in many very serious accidents

and acts of sabotage.

But as noted in section

Boron the Unignitable

it doesn't by itself make boron unique or even very unusual.

What is unusual,

and helps make this alternative fuel truly an alternative with a difference,

is its high energy density,

per pound and especially per gallon.

A chamber for it plus a bin for all the glass ingots it will become

would together be not much larger than the liquid hydrocarbon tank they replace.

Sections Boron the Dense

and If a Car Retains All Its Ash give comparative data.

A compact energy reservoir should mean plenty of range.

Release of the energy in a hot flame at high pressure should mean

good ratios of power to mass in boron motors,

and quickness in boron cars.

People who read about global warming will want them,

but so will people who don't read the papers at all.

Voluntary customers will line up around the block.

Where Has Boron Been Hiding?

Can boron power be as good as is here let on

and yet not have been envisioned before?

At least one necessary technique may be intractable

or may only recently have ceased to be so:

Purifying Air Oxygen On Board a Vehicle

in the quantities necessary to power that vehicle.

Also, once pure oxygen is available,

it will have to be prevented

from burning the motor along with the fuel.

The section titled Is This in Any Way New?

briefly discusses an investigation of decades ago

that may have put people off.

Some still confuse boron with boranes.

Beginning with section Boron of the Bright Flame

basic data pertinent to boron's performance as a fuel are presented.

Why Boron Motors Won't Emit

Why Boron Motors Won't Emit

How can hot combustion in a flame be reconciled with zero emissions?

Nature's answer seems to be boron.

Its oxide uniquely combines oozy plasticity at hot motor temperatures

with stony solidity below 200 Celsius --

although unfortunately not complete waterproofness --

so that it can readily be molded into ingots.

|

|

| |

|

Pressed-glass form (RASA Industries photo) in

pure boria. Some squares have concave tops

due to interior shrinkage while congealing

|

|

That such ingots will in fact be made

is ensured not just by boria's cooperative nature

but also by boron's salvage value.

Vehicle operators need not be as nice as boria for this to work.

All the ash will be retained and recycled

(cf. Boron Decombustion),

none will be emitted.

Power-generating internal boron combustion also doesn't lend itself

to burning and emitting nitrogen.

Boron fuel cells may be possible,

but, unlike the case with hydrogen,

would have no edge in cleanliness over boron combustors.

Cars in which boron fuel simply burns will be true zero emission vehicles.

Combustion simplified

Some of what boron can do,

anything that burns to an involatile ash can in principle do too.

ash can in principle do too.

For instance, magnesium, chemical symbol Mg.

Seven pounds of it carries as much energy as three pounds of boron

(cf. Boron the Energetic).

If it were burnt in excess pure oxygen,

the only chemicals downstream of the flame would be gaseous oxygen

and solid particles of magnesium oxide (MgO ).

).

Some of this fine dust would readily fall out.

A remnant would make the mixture appear as white smoke

if it were released.

But it's nearly pure oxygen.

Releasing it would make no sense.

If instead it is sent back to oxidize more magnesium,

it does this just as well as new oxygen.

The suspended ash from last time doesn't interfere.

Pure oxygen is costly, but this way very little is wasted.

Each atom of leftover oxygen emerging from the flame is repeatedly sent back

until it is consumed.

No large volume of gas ever gets out.

The only final effluent is precipitated MgO powder,

plus a little entrained oxygen between grains and on their surfaces.

In general...

As above shown,

ash involatility allows pure oxygen to be used at once sparingly, and in excess.

This makes combustion almost ideally simple:

- all the fuel burns

- nothing else burns (nothing else is there)

- almost nothing but dense precipitated ash comes out.

|

|

|

Magnesium in air (video).

Courtesy C. E. Jones,

University of Texas Austin.

|

|

|

Allows, but does not require.

Many of us have ignited magnesium ribbon in air with a match.

If there were some reason to run cars on magnesium,

they too could burn it in plain air.

Combustion complicated

But using plain air would inevitably lead to ash venting.

As with pure oxygen, some ash would remain in suspension,

but now the gas it would be in couldn't return to the flame.

Having begun as air, 78 percent nitrogen,

it would have an even higher nitrogen content after one flame pass.

So it would be trash.

It couldn't go back and react more.

Nothing could be done with it except dump it as waste gas.

With it would go the magnesium oxide that didn't precipitate

and the (generally considered harmful) oxides of nitrogen.

So if metallic magnesium existed in huge natural deposits,

car makers designing for it might face a moral dilemma.

Take the pure-oxygen high road?

This gives a zero emission vehicle by eliminating oxides of nitrogen,

even though they would not be visible anyway.

It allows all the (worthless) MgO to be kept on board,

and so puts the operator in charge of it, willy-nilly.

Or simply burn it with air and let the smoke and fumes go?

Boron to the Rescue

Do designers of both B buggies and Mg-mobiles face this same dilemma?

Pure oxygen and cleanliness, or letting air in and smoke out?

Several factors contribute to an answer:

No.

One could never get away with discharging boria as smoke.

The particles would quickly combine with atmospheric water vapour

and become boric acid particles.

Boric acid is soluble,

and like oxygen can enter the bloodstream through the lungs.

In small quantities it may be necessary to animal life,

and is definitely harmless,

but the tonnes per day

that could be generated at a busy urban intersection

would be intolerable if dispersed there.

No.

One could never get away with losing boria as smoke.

Unlike magnesium, boron is a somewhat rare element.

In recent years its mining cost has been

roughly one order of magnitude more than the retail cost

of the energy it can carry.

If it made only one trip,

boron to deliver a dollar's worth of energy would cost roughly ten dollars.

Economy requires the same boron to be used many times.

The ash must be kept.

No.

Pure solid boron needs concentrated oxygen just to light

(cf. Boron the Unignitable).

There is no prospect of setting it on fire just with air.

The last point really may be only 0.99 of a No.

The crudest oxygen pure boron can readily ignite in is not as dilute as air,

21 percent, but still may be substantially below 99 percent.

It doesn't matter.

The first two factors push the required oxygen purity

from wherever that minimum is, on up to High.

They do this by demanding the combined level of all other gases,

which sweep ash out rather than becoming part of it, be Low.

But the unignitability factor backs them up.

It guarantees that even if there were no reward for keeping boron ash,

and the penalties for its dumping were either nonexistent,

or limited to persons other than the customer,

a designer still couldn't delete the oxygen separator.

See also Internal Boron Combustion Engine Considerations.

Conclusion: with boron there is no dilemma

In general if a fuel has involatile ash simplified combustion is merely possible,

but with boron it's the only possibility.

This means oxides of nitrogen will not be formed,

as said at this section's beginning.

Nitrogen is kept out of the boron flame primarily for

other reasons than preventing this oxidation,

but even so it is prevented.

Aluminum?

One reader suggests

aluminum's boron-like ignition resistance

and the limitless availability of its oxide (the mineral corundum)

might make it preferable despite a weight penalty

(cf. Boron the Energetic).

But while boron is rare to what seems like just the right degree,

aluminum's very abundance would tend to zero the salvage value of its ash.

Like magnesia, it would in all likelihood be dumped.

Maybe as smoke, maybe in bags,

but in either case no-one's name would be on it.

Basic boron data follow.

The main introduction is above.

Boron of the Bright Flame

Boron of the Bright Flame

Starting from 25 Celsius,

pure boron and a four-thirds excess of pure oxygen at 100 bars pressure

reach a maximum flame temperature of 4,370 Celsius.

Under the same starting conditions

hydrocarbons and hydrogen burn cooler by about 1,000 K .

.

Here are the basic oxidation process data for boron and some other materials

at 25 Celsius.

The energy yields are shown as negative numbers because before reaction

the energy is in the reagents , and when they react they lose it.

, and when they react they lose it.

| Reagents |

|

Products |

DG / /

(kJ/mol) |

B(s) + 3/4O2 |

|

1/2B2O3(gls) |

-590.76 |

Al(s) + 3/4O2 |

|

1/2Al2O3(s) |

-791.15 |

1/2H2(g) + 1/4O2 |

|

1/2H2O(g) |

-114.30 |

C(s) +

O2 |

|

CO2(g) |

-394.41 |

1/26C8H18(l)+25/52O2 |

|

9/26H2O(g)+4/13CO2(g) |

-200.64 |

|

The above data compare oxidizable atoms one for one.

So they compare one mass of hydrogen to

26.77 masses of aluminum (Al),

11.92 of carbon,

10.73 of boron,

and 4.36 of 3-ethyl-3-methylpentane,

an octane isomer that is a fairly representative component of gasoline (petrol) .

.

Since aluminum and boron atoms similarly combine with 1.5 oxygen atoms each,

and per aluminum atom the yield is more,

an aluminum-oxygen flame should be hotter and brighter than a boron-oxygen one.

No photo of the boron kind is available yet,

but a large aluminum one can be seen in section

Boron the Unignitable.

Removing the minus signs,

inverting (e.g. rewriting 791.15 kJ per mole of aluminum as

0.0012640 moles of aluminum per kilojoule),

and multiplying by molar masses and volumes gives

fuel mass and volume requirements per unit energy.

The next several sections do this arithmetic

for the above substances and some others.

Smaller numbers are better,

and where display and browser permit,

they appear on darker backgrounds.

Boron the Energetic

Boron the Energetic

Here in kilograms is how much of several elements of low atomic number

(shown in lower left corners)

must be oxidized to yield a gigajoule.

Volumes are given in section Boron the Dense ...

|

|

| |

3-ethyl-3-methylpentane

|

| 2.54 |

21.90 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

... and Energy-Specific Ash Mass

gives the post-oxidation masses.

The amounts of oxygen taken up are the subject of

Boron the Oxygen-Sparing.

Only light elements carry oxidation potential energy lightly.

At 30 kg/GJ carbon's entry is less than any in the rows below it,

and would be so even if the whole periodic table were included.

The fifth, fourth, third, and especially the first element, hydrogen,

all come in lower still;

and by virtue of containing a little hydrogen,

so do today's fuels.

They are complex mixtures of liquid compounds

that mass 20 kg or more, mostly carbon, per gigajoule.

One compound fairly near that minimum

has been allowed to hide among the elements above,

but can be spotted by its noninteger atomic number.

Its presence highlights the fact that

while boron's kg/GJ score is more than twice hydrogen's,

it is still entirely below the range of today's fuels.

Boron the Oxygen-Sparing

Boron the Oxygen-Sparing

When we produce energy by fuel oxidation,

we are also producing it by oxygen reduction.

Some fuels reduce more kilograms of oxygen per gigajoule yielded,

and some fewer.

Data follow.

|

|

| |

O2(3-ethyl-3-methylpentane)

|

| 2.54 |

76.68 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

O2(Zinc) |

| 30 |

49.92 |

|

|

|

|

|

Boron is a fairly deep chemical energy well for oxygen,

less so than metals just below it and to its left,

but in section Energy-Specific Ash Mass,

when its own lightness is added in, it beats some of them.

Hydrogen, carbon, and a typical fuel hydrocarbon

take almost twice the oxygen boron does.

Energy-Specific Ash Mass

Energy-Specific Ash Mass

Here are the kilogram amounts of oxide produced by complete oxidation

of a gigajoule's worth of various substances.

The space these oxides might be packed into is given

in section Ash Volumes.

|

|

| |

3-ethyl-3-methylpentane

|

| 2.54 |

98.57 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

Section Boron the Energetic

gives the pre-oxidation masses.

Boron scores lower than carbon and a typical fuel hydrocarbon

in Boron the Energetic

and Boron the Oxygen-Sparing,

but higher than beryllium .

The same order exists here because this chart just sums those other two

.

The same order exists here because this chart just sums those other two .

.

Hydrogen's entry shows that it isn't the lightest of oxidizable fuels

if the weight of the necessary oxygen is counted.

Carbon, hydrogen, and their compounds might be considered

as making no ash at all,

if fuel-oxidation-derived invisible vapours didn't count as ash.

In this document, they do.

Boron the Dense

Boron the Dense

Below are the various light oxophiles' volumes

in litres per gigajoule of oxidation potential energy.

The corresponding masses, kilograms per gigajoule, are given in

Boron the Energetic.

|

|

| |

3-ethyl-3-methylpentane

|

| 2.54 |

30.10 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Carbon  |

| 6 |

13.43 |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

Section Ash Volumes

shows the large expansion or shrinkage that can result

when oxygen attaches itself.

In section Let Your Car Bore On

boron's decent showing is partly due to its being tops here .

.

Ash Volumes

Ash Volumes

In how few litres of space can the oxide from a billion joules' worth of oxidation fit?

Below are some data.

The masses of these amounts of oxide are

given in section Energy-Specific Ash Mass.

Section Boron the Dense

gives pre-oxidation volumes, not including uncombined oxygen volume.

In Let Your Car Bore On

fuel and ash volumes are combined.

The eight small values of which aluminum's 16 L/GJ is typical

are oxide crystal volumes for the stablest forms at room temperature and pressure.

So if an aluminum-oxidizing power system

dealt with its ash by making it into a huge flawless sapphire,

that is how big the sapphire would end up.

This would not actually happen.

The two largest values, carbon's and 3-ethyl-3-methylpentane's,

are about 400 times smaller than they would be

if their carbon dioxide volume component referred to the

room-temperature, room-pressure gas.

In fact it is counted as pressurized room-temperature liquid.

The 79 L/GJ entry for hydrogen is the best approximation

to the volume an ash chamber in an actual power system would need,

because liquid water packs down well.

It is also the ash least likely to need keeping at all.

Let Your Car Bore On

Let Your Car Bore On

How big are the tanks, really?

Answers are given here in terms of litres per three gigajoules,

not one,

because 1 GJ of fuel energy propels a typical car only about 300 km,

and 1,000-km range is not very unusual.

|

|

| |

3-ethyl-3-methylpentane

|

| 2.54 |

90.30 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

The 140-L entry for boron is 108 L for ash, 32 L for fuel .

This is based not just on tripling the data from Ash Volumes

and Boron the Dense

but on multiplying them by further factors of roughly 1.5

.

This is based not just on tripling the data from Ash Volumes

and Boron the Dense

but on multiplying them by further factors of roughly 1.5 .

These extra adjustments allow for imperfect packing of solids.

.

These extra adjustments allow for imperfect packing of solids.

For liquid ammonia and liquid hydrogen those two sections' data,

summed and tripled, exceed the fuels' entries in this chart.

Only contained volume counts here,

and these fuels' ashes need no containment.

They can disperse harmlessly into the planetary atmosphere.

Using that same convenient ash bin,

3-ethyl-3-methylpentane and carbon show the same fuel-only compactness

to a much greater degree.

Carbon-free fuels can fit in reservoirs nearly as small,

but only if they are also hydrogen-free,

and much of the enclosed space then is for ash!

If a Car Retains All Its Ash

If a Car Retains All Its Ash

Boron's unique compactness suggests a car burning it could easily

have transcontinental range.

However, boria needs to be recycled.

The simplest way to ensure this happens is to keep it all on board

until it can be swapped for more boron.

That means

a 1,000-km boron fuel reservoir's worst-case volume is the sum of the volumes

of 1,000 km worth of boron before use and the same boron in oxide form after use.

The table below shows this sum is 129.9 litres.

A representative liquid hydrocarbon looks a little better at only 90.3 litres,

but this includes no space for waste oxide

after use.

The table below shows this sum is 129.9 litres.

A representative liquid hydrocarbon looks a little better at only 90.3 litres,

but this includes no space for waste oxide .

.

To propel a car 1,000 km (621 miles) at 125 km/h

|

| Combustible |

Volume/L |

Mass/kg |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Fuel H3C·C(C2H5)3 |

| Ash 8 CO2 + 9 H2O |

|

| 90.3 |

102,500  (202.5 kg CO2) (202.5 kg CO2) |

|

|

Methanol  |

| |

|

| Fuel CH3OH |

| Ash 2H2O + CO2 |

|

| 177.3 |

| 97,500 (192.7kg CO2) |

|

|

|

|

|

373.8  |

237.1  |

|

|

In practice, since boria is solid, it has a packing fraction

-- there are voids between lumps --

and the total volume may be more than 129.9 litres.

Perhaps as much as 150 litres, 66 percent more than equivalent gasoline (petrol).

This is less than half the 373.8 L liquid hydrogen volume .

.

A Preliminary Conclusion

A Preliminary Conclusion

To the question of this document's title

the answer suggested by the data above is plainly Yes.

As a synthetic fuel, boron is better than hydrogen.

This is true

even though hydrogen carries much more energy per unit mass than boron.

A pound of boron replaces 1.2 pounds of liquid hydrocarbon,

a pound of hydrogen replaces 2.5 pounds of it,

so it might seem hydrogen replaces 2.1 times its mass in boron.

That's not how it works out.

Boron's compactness means

a gallon of boron replaces at least 11 gallons of liquid hydrogen.

The boron is heavier.

But its inert solidity allows its safe containment in (e.g.) a paper bag,

where liquid hydrogen requires a tank that is not just 11 times roomier on the inside,

but thick-walled, to keep the cold in.

The weight of boron plus bag is less than the weight of hydrogen plus cryogenic containment.

By fitting the same energy in a smaller space under a car's skin,

boron allows a small drag reduction.

This makes the required boron inventory a little smaller yet,

or gives the same range at a greater speed.

Plus there are boron's advantages of not evaporating no matter how long the car sits,

and being unable to burn by accident.

Boron the Unignitable

Boron the Unignitable

Boron's major safety advantage is that it strongly resists ignition.

|

|

| |

|

B on glass at 600-800°C,

in air, from video courtesy

C.E. Jones, U. Texas Austin.

|

|

Shown are a few milligrams of pure boron particles

sitting inert in air, although nearly red-hot, on a borosilicate glass dish.

If they were to oxidize slowly,

they would literally fade into the background.

What stops them may be the formation of a heat-resistant oxide film .

If on each tiny grain the outermost few layers of atoms did oxidize,

they might then, as oxide, protect all the much more numerous atoms within.

.

If on each tiny grain the outermost few layers of atoms did oxidize,

they might then, as oxide, protect all the much more numerous atoms within.

This helpful behaviour is commonplace among metals

but unusual in nonmetallic elements.

It is unusual in fuels,

except for one odd case of a fuel that is a metal,

and has a very high flame temperature,

and in air can't be ignited with a blowtorch

because its superficial oxide layer is so strongly protective.

Aluminum is rocket fuel

|

|

|

|

NASA knows how to burn aluminum

|

|

|

|

|

|

Oxidation yields the same energy with three pounds of aluminum

as with only two pounds of a typical hydrocarbon

(cf. Boron the Energetic).

But combustion rockets must lift oxygen as well as fuel,

and when both reagent masses are accordingly counted,

the totals come out near six pounds for aluminum

versus nine for the hydrocarbon

(cf. Energy-Specific Ash Mass).

Some rockets therefore run on solid propellant

that is a mixture of finely divided aluminum, solid oxidizer, and glue.

The bright plume from such a rocket is shown.

Yet every day

millions of pots with aluminum alloy bottoms

are put on red hot stove coils by millions of people

who quite sensibly give no thought at all to the potential for aluminum combustion.

None occurs!

When the pots are forgotten, whatever is in them first boils or burns away,

and then near 600 Celsius the aluminum melts and runs down through the coils.

It does not ignite.

Like heavy boron only ductile, fusible, metallic, not dark brown ...

Aluminum, the next heavier element after boron

in the periodic table column they share, actually isn't very much like boron.

But the similarity in resisting ignition and oxidation is close.

The familiar example of aluminum is a good guide to boron's ignition behaviour.

There are some minor differences.

Refractory liquid barrier

Boron's oxide coat is unusual in that

at temperatures between 450±2 Celsius and roughly 2,000 Celsius

it is a very viscous liquid coat.

Also, boron itself is still solid at 2,000 Celsius.

So at temperatures like those of the boron photo,

boron is a solid protected by a liquid oxide film,

and aluminum would be liquid protected by solid.

It melts 660.37 Celsius, its oxide melts at 2,015 Celsius.

A liquid boria film's high viscosity makes it act just like a solid barrier,

except that if a gap somehow forms,

and air gets momentarily through,

the gap tends to get resealed not only by the creation of new oxide

but by the lateral flow of the oxide next to the gap .

.

This thick fluidity also prevents gaps from being created in the first place.

Liquids have no cracks.

In most metal oxides and in boria

the oxidized atoms are farther apart than they were in pure element.

So an oxide coat that gets thick

gets too big for the metal object it is growing on.

This is true for aluminum and beryllium,

but not for magnesium.

Magnesium atoms in the metal get closer together

when oxygens take up residence between them,

so an oxide coat develops tension, not compression, as it thickens.

Cracking and shrinking, re-exposing naked metal,

would help to explain the unboronlike behaviour shown in the section titled

Why Boron Motors Won't Emit.

A hot boria coat can flow,

so despite the boron atoms' moving apart on oxidation no compressive stress builds up.

No matter how thick the coat gets it remains seamless.

No oxygen can penetrate it except by diffusion.

When a coat reaches more than a few microns in thickness

this becomes a slow process .

.

Boron the inert

Another way

this nonmetal differs from combustible metals is its great inertness at room temperature.

Aluminum seems inert because its oxide coat is inert.

A bare aluminum surface reacts instantly with air or water.

The water reaction can be confirmed by putting an aluminum surface under water

and there scratching it with a file.

The new surface takes oxygen and leaves hydrogen,

which appears as minute bubbles.

However, a naked boron surface in air can remain naked,

or cover itself only with adsorbed air molecules as graphite does.

This paradoxically means it may be possible

for a suspension of fine boron dust in air to be explosive,

like flour or cornstarch.

Finely divided boron is very abrasive,

so even if it were too coarse to stay aloft it would not be a preferred fuel form.

Long boron filaments coiled into massive coils seem like a better idea.

A free end can be pulled off and go into a motor and burn at the tip.

and burn at the tip.

This way boron is unignitable only until we need it not to be.

In the motor the tip of the filament will be exposed on all sides to oxygen

and out of thermal contact with other parts of the coil.

Out in the reservoir coil the opposite is true,

so if a cosmic ray strikes one loop of filament and makes a hot spot on it,

its neighboring loops are there to conduct the heat away

and atmospheric oxygen has less access because they are in the way.

Also, while the still coiled loops are exposed only to dilute atmospheric oxygen,

the piece in the chamber is in pure oxygen at much higher pressure.

In this environment it is expected that a flame can sustain itself

and advance along the fibre leaving nothing but oxide behind.

Purifying Air Oxygen On Board a Vehicle

Purifying Air Oxygen On Board a Vehicle

The essence of boron power is compact energy storage

in innocuous dry involatile solids.

Consistency with this demands that oxygen be taken from ambient air.

It will not come from onboard tankage,

for if so kept it would be hazardous, bulky, volatile fluid.

The boron power system it was in would thus be a travesty.

But as shown in Boron the Unignitable,

boron is unignitable in the 21 percent oxygen that air is.

Although it might light pretty well in 70 percent oxygen,

compelling advantages of economy and cleanliness are gained

if the purity is much nearer 100 percent

(cf. Why Boron Motors Won't Emit).

So when boron power systems take oxygen from the atmosphere,

they'll take it neat, and leave the other stuff outside.

Is There Enough Energy?

Suppose a heat engine turns 30 percent of the thermal power it generates into mechanical power

and lets the other 70 percent depart unconverted.

An oxygen purifier will probably have no use for the waste thermal power;

instead, it will demand some of the scarcer resource, the mechanical power.

Will it demand all 30 percent?

Will it demand all that and another thousand?

No.

If Today's Hydrocarbon Motors Needed Pure Oxygen ...

They don't, and probably would burn up in it.

But if they did need it, they wouldn't be stuck.

At the supposed 30 percent gross thermodynamic efficiency,

they consume 260 kg of oxygen

for each gigajoule of produced mechanical energy,

according to the data in section

Boron the Oxygen-Sparing.

This particular proportion of energy to oxygen

has not figured in the design of today's air separators.

A high (kg O2)/GJ number has been only one of several goals,

and getting it well above 260 has not been critical.

Nevertheless, it is there.

Industrial-scale zeolite-based oxygen purifiers today give 430 (kg O2)/GJ.

If one of these had wheels,

and its power source were a built-in hydrocarbon motor,

and the motor had no source of oxygen but the purifier's output,

it would be more than enough.

170 (kg O2)/GJ would be net product.

Alternatively, the net oxygen output could be zeroed,

the motor taking it all,

if each motor output gigajoule were divided into

600 megajoules for the purifier

and 400 MJ for the wheels.

The thing could go.

Boron Motors Do Need It, But Not So Much

Section Boron the Oxygen-Sparing also reveals,

not without forewarning,

that boron motors will need less oxygen than today's.

At the supposed 0.30 gross thermodynamic efficiency,

they will need 140 (kg O2)/GJ.

That means the self-powering, self-propelling oxygen purifier

with its hydrocarbon motor replaced with a boron one

could apportion a gigajoule of motor output thus:

330 MJ for the purifier, 670 MJ for the wheels.

One useful attribute for industrial oxygen purifiers is

the ability to stay in place and working

despite occasionally being backed into by forklift trucks.

They are sturdy .

Converted to self-propulsion, they would not be fast rides,

but they'd be faster with boron motors than gasoline ones,

especially if both types of motor were scaled to drive

the purifier at the same throughput.

.

Converted to self-propulsion, they would not be fast rides,

but they'd be faster with boron motors than gasoline ones,

especially if both types of motor were scaled to drive

the purifier at the same throughput.

How Much Better Can It Get?

Thermodynamics provides one answer to this question.

Section Boron of the Bright Flame

presents boron's oxidation process this way,

| Reagents |

|

Products |

DG/

(kJ/mol) |

B(s) + 3/4O2 |

|

1/2B2O3(gls) |

-590.76 |

|

but from an atmospheric oxygen purifier's viewpoint it really looks like this:

| Reagents |

|

Products |

DG/

(kJ/mol) |

4/3B(s) + 4.774(air) |

|

4/3B +

O2 +

3.774(azotics) |

+6.07 |

4/3B +

O2 |

|

2/3B2O3 |

-787.68 |

|

The first line is the absolute minimum energy cost of purifying oxygen,

setting aside the other gases that do not support combustion.

They are denoted by "azotics" since they also don't support life.

The second line is how much energy the oxygen then can yield with boron.

In theory, then, one watt of power fed to an oxygen purifier

could be deducted from 130 watts yielded by a boron power system

downstream of that purifier.

In reality that can never happen,

but one can do a lot less well than that, and still do very well.

Oxygen Purification Based On Its Paramagnetism

|

|

|

|

Cobalt atoms magnetically aligned on polymer backbone.

|

|

|

Oxygen is the only common substance in air that is weakly attracted by

a magnet. Other gases are weakly repelled.

Polymers have been made experimentally

that contain rows of aligned tiny magnets -- cobalt atoms.

These rows act as corridors that hinder the motion of oxygen molecules

in directions not parallel to the polymer chain.

|

|

|

|

Dioxygen molecules' magnetically constrained motion

Both diagrams courtesy H. Nishide.

|

|

Other types of molecule will diffuse in all directions,

but dioxygens will hop along the polymer backbone.

The diffusion rate of oxygen is claimed to be 40 times that of nitrogen .

That means two stages of filtration through this material

would give adequately pure oxygen for a boron motor.

The first stage would raise the ratio of oxygen to nitrogen from the 0.26825

that exists in air to 10.7, and the second would raise it over 200.

.

That means two stages of filtration through this material

would give adequately pure oxygen for a boron motor.

The first stage would raise the ratio of oxygen to nitrogen from the 0.26825

that exists in air to 10.7, and the second would raise it over 200.

Efficiency might require this to be done at high pressure.

Pure oxygen and a hydrocarbon polymer could not then safely coexist.

One useful development of this technique therefore would be

to replace the organic backbone with one

that was already full of chlorine, oxygen, or fluorine,

i.e. a ceramic, or maybe a halocarbon polymer.

Boron Decombustion

Boron Decombustion

The Earth contains uranium and thorium

that over a two-million-year period could produce 175 petawatts

(175 PW, 175 trillion kilowatts).

This is also the total power of the light and other radiations

that continuously come to Earth from the Sun,

and are reliable for the next 2,000 such periods at least.

Averaged over its lifetime a modern car's power draw is a few kilowatts.

Appropriating the whole 175 PW to support 50 trillion cars and drivers

probably is a bad idea,

but diverting an unobtrusively small fraction will still support many

billions of them.

So the Earth can't be short of propulsion power for vehicles,

not now and not in the year 1000000.

Or at least, it can't be

if solar or nuclear power can be brought to bear on ash from combustion motors

in such a way that it turns back to fuel.

What follows is one possible way to do this with boria,

a way that takes most of its input energy in the form of heat.

Sulfur

First the boria will be melted and

have sulfur vapour bubbled through it.

Sulfur likes to combine both with oxygen, making sulfur dioxide,

and with boron, making diboron trisulfide.

| Reagents |

|

Products |

DG°/(kJ/mol) |

1/2B2O3(l) + 9/8S2(g) |

|

1/2B2S3 + 3/4SO2 |

+156.89 |

|

If, as seems fitting, this reaction occurs

then the two sulfur compounds won't stay together.

The sulfur dioxide will stay in the gas bubbles,

and the boron sulfide in the liquid,

which will become mixed oxide and sulfide.

The positive number in the third column above means that

at 25 Celsius the sulfur compounds in the Products column

are that much higher in energy than the sulfur and boria in the Reagents one.

What could provide the extra energy?

than the sulfur and boria in the Reagents one.

What could provide the extra energy?

Heat.

Sulfur bubbles will be injected at the bottom of a vat of liquid boria

that will start out hot, around 1,000 Celsius.

As they rise through the liquid the bubbles will lose sulfur to it,

take oxygen from it,

and even if the vat is well insulated,

the whole mixture will cool.

Heat will have been transformed into chemical energy.

If this continues the liquid will cool and stiffen

until bubbles are effectively trapped.

Heat from a solar collector or nuclear reactor must be added.

When this is done, a continuous countercurrent process is possible:

pure boria in at the top,

partially sulfided material out at the bottom.

Pure sulfur vapour in at the bottom, partially oxidized sulfur out at the top.

Constant temperature maintained by constant addition of heat.

Does this give us the indirect nukemobile and the indirect solar car?

Not quite yet, not unless they can usefully burn impure boron sulfide,

and they can't.

Plus, so far, much of the energy in that sulfide isn't solar or nuclear,

it's sulfur energy.

There is sulfur in the Earth,

but if burnt at 175 PW,

it would all be gone in a few minutes.

Also the resulting sulfur dioxide shouldn't just be let go.

Because boron and oxygen burn so strongly together,

getting them apart again is hard.

This first step may seem to have, indeed it has,

accomplished this at the expense of creating two new problems,

but they're both easier problems.

The fate of the sulfur dioxide will be discussed a little later.

For now the focus is what happens to boron sulfide.

Bromine

Mixed boria and boron sulfide

emerging from the bottom of the sulfur percolation vessel

will enter another vessel

and have another gas bubbled up through them.

The gas this time is the halogen, bromine.

The boron atoms that lost their oxygen to a bubble

now will be taken off as gas in their own turn.

| Reagents |

|

Products |

DG°/(kJ/mol) |

1/2B2S3 + 3/2Br2(g) |

|

BBr3(g) + 6/8S2(g) |

-56.82 |

|

The negative number in the right column shows

bromine would consume boron sulfide,

converting it to a gaseous mixture of tribromide and sulfur,

even if the gases remained mixed with the liquid sulfide,

even without any addition of energy.

This treatment dismantles and lifts out all the boron sulfide

and leaves the boria alone.

So the liquid becomes once again pure boria,

not quite as much as first entered the sulfur percolation vessel.

It will return there now,

along with additional boria to make up the loss.

Hydrogen Reduction

A hot boron surface can lose heat and gain boron if it is in contact

with a gaseous mixture of boron tribromide and hydrogen.

This is an established way of growing boron filament:

| Reagents |

|

Products |

DG°/(kJ/mol) |

BBr3(g) + 3/2H2 |

|

B + 3HBr(g) |

+70.92 |

|

Since boron is dark brown

(see photo in introduction)

and hydrogen bromide, hydrogen, and boron tribromide are all transparent,

there is an interesting possibility of using intense light

directly to heat the advancing boron surface.

Conquering the Divided

The sulfur that was combined with boron

has already been run out of there by bromine,

and so allowed to return to the sulfur percolation vessel.

The rest is in sulfur dioxide, which must be broken into its elements.

As must the hydrogen bromide:

| Reagents |

|

Products |

DG°/(kJ/mol) |

3HBr(g) |

|

3/2H2 + 3/2Br2(g) |

+164.78 |

3/4SO2 |

|

3/8S2(g) + 3/4O2 |

+254.99 |

|

The Whole Process

Here are the above five steps all together.

| Reagents |

|

Products |

DG°/(kJ/mol) |

1/2B2O3(l) + 9/8S2(g) |

|

1/2B2S3 + 3/4SO2 |

+156.89 |

1/2B2S3 + 3/2Br2(g) |

|

BBr3(g) + 6/8S2(g) |

-56.82 |

BBr3(g) + 3/2H2 |

|

B + 3HBr(g) |

+70.92 |

3HBr(g) |

|

3/2H2 + 3/2Br2(g) |

+164.78 |

3/4SO2 |

|

3/8S2(g) + 3/4O2 |

+254.99 |

|

Leaving out things that are produced in one reaction and consumed in another,

and adding up the DG° numbers,

| Reagents |

|

Products |

DG°/(kJ/mol) |

1/2B2O3(l) |

|

B + 3/4O2 |

+590.76 |

|

A combustion process that goes forward in one step

has been forced backwards in five.

-- Approximately five.

Sulfur dioxide and hydrogen bromide decompositions aren't as simple as above shown.

Followers of the long-rumoured "hydrogen economy" will recognize the

similarity to thermochemical water-splitting schemes.

But those schemes had fewer steps,

because from hydrogen down to water it's energetically

a lot less far than from boron down to boria.

Is It Worth It?

Is the increased complexity worth it?

One reason why it actually seems like a pretty good bet is this:

it never hurts to make some boron ahead.

Consider two power plants.

Each turns 20 or 30 gigawatts of heat into 10 GW of chemical fuel.

This is larger than usual for electric power plants today

but an ordinary size for oil refineries.

One makes hydrogen, the other makes boron.

If the boron plant has no takers for a couple of weeks,

it can stack boron outside, perhaps on pallets,

40 acres six feet deep.

Rain won't hurt it.

The hydrogen plant might also store two weeks' production,

not, of course, in contact with the elements --

earth and water are OK, but definitely not air or fire --

but perhaps as the inflating gas in a kilometre-wide

gas supported tent 250 m high at the centre.

This is about five times more area than the pallet field,

and seems certain to cost more per unit area.

Boron the Ubiquitous

Boron the Ubiquitous

There is enough boron on Earth

that plants rely on it to be in their soil in dissolved oxide form.

They suffer if there is too much or too little .

.

A million tonnes of seawater contains 4.4 tonnes boron.

This makes the oceans a reserve such that if the first pound is not too expensive,

many more pounds are available at the same price.

After a thousand cubic miles of boria have been removed,

the concentration still is pretty much as it was.

One way to extract it would be to impound a large amount of seawater

and let it dry up.

Different components of sea salt precipitate at different times as the salt concentration increases

and it is possible to get a borate layer.

layer.

Nature has done this,

and on a scale large enough to support an industry

that annually extracts ready-concentrated, cheap borates

containing a quarter of a million tonnes of boron .

Much of this boron has passed through people's houses,

particularly their laundry rooms,

in the form of perborate bleach or borax.

Much less than one percent has been separated from its oxygen.

.

Much of this boron has passed through people's houses,

particularly their laundry rooms,

in the form of perborate bleach or borax.

Much less than one percent has been separated from its oxygen.

Is It Possible to Run Out?

Known reserves are several tens of millions of tonnes of boron.

At current consumption rates, mostly for glassmaking,

that is several times 40 years' worth .

.

Each boron car that comes into being will require some kilograms on board,

and a few times that much in transit to and from a decombustion plant,

but once this has been provided it can just keep going around.

One way to look at the boron atoms

is as a multitude of little energy-transfer machines,

incapable of wearing out,

easy to keep herded together both when laden and when empty.

So there is plenty of boron for a few hundred million boron cars.

When more are desired,

it may be necessary to bring a minute fraction

of the ocean's boron onto land.

Boron the Peripatetic

Boron the Peripatetic

Coils of boron filament can get from the plant that makes them

to the devices that burn them by any ordinary kind of freight carrier,

with none of the restrictions necessary for today's energy-bearing chemicals.

One could mail five pounds of boron in a parcel

but the mails will not accept a gallon of gasoline.

It also is very easy to store boron.

When buying a car one could buy a lifetime supply of boron coils for it

and keep them in the back yard.

One would probably prefer to have them under some kind of cover .

.

The awkward but interesting parts come after the boron has been burnt.

If we visualize a small piece of boron filament

passing through a reaction zone where oxygen consumes it,

immediately downstream of the zone

we see it as a short section of a stream of very hot, very luminous boria vapour.

In a heat engine this will not be the working fluid all by itself; it's too hot.

Rather, its heat must be spread through some

surrounding fluid by mixing and by absorption of its light in that fluid.

Suppose for a moment that the mixing mass ratio is four masses of

fluid to one mass of boria, and the fluid is helium . Helium molecules are much

less massive than boria ones so a four-to-one mass ratio means

a 70 to one molecule ratio.

Heat capacity is per molecule so a good

approximation of the temperature rise can be found by treating the helium's

constant pressure heat capacity as the only heat capacity present.

715 K is the result.

. Helium molecules are much

less massive than boria ones so a four-to-one mass ratio means

a 70 to one molecule ratio.

Heat capacity is per molecule so a good

approximation of the temperature rise can be found by treating the helium's

constant pressure heat capacity as the only heat capacity present.

715 K is the result.

The temperature rise will be less if the boria remains in the vapour state;

but it won't.

For reasonable or even enthusiastic starting and ending temperatures,

e.g. 700 Celsius start, 1,415 Celsius end, it will condense.

It will exist as an aerosol,

or perhaps a helium-osol: a suspension of liquid droplets.

If the aerosol now expands through a gas turbine,

many of the droplets will stick to the turbine blades and run down them.

Since they are rapidly rotating,

"down" is not towards the centre of the Earth,

it is towards each blade's outer end.

So at first glance

a gas turbine seems to lend itself to continuous separation of boria from the working fluid .

.

Is a Gas Turbine the Way?

Let's assume so and see where it leads.

Something will have to happen to the parcel of oxide

when it gets to the ends of the turbine airfoils.

The centrifugal force field strength is at its maximum there,

so as long as a path is open to the oxide

that lets it continue to get farther from the axis of rotation,

it will keep moving.

Since the turbine channel where this is happening is an expansion channel,

the working fluid gets to wider places as it moves along and works.

The liquid boria can get farther out by going in the same direction.

The fluid is getting cooler.

Since the boria is flowing along parallel, it too may be cooling .

This will make it more viscous.

.

This will make it more viscous.

Where boria finally exits the expansion turbine

a glass-molding mechanism can take it and shape it.

It can be worked by the same methods as ordinary bottle glass,

but at a lower temperature.

The temperature where the viscosity of a type of glass is one million times that of

water at 20 Celsius is known as its working point,

and for bottle glass it's between 1,000 Celsius and 1,050 Celsius.

For boria it's 550 to 575 Celsius.

In a big car that is already at highway speed and accelerating rapidly

the motor might be pulling boron filament in and burning it at the rate of 0.014 kg/s .

This gives 810 kilowatts of heat and 0.045 kg/s of boria glass.

That is 25 cubic centimetres per second,

about the rate a toothpaste tube will give if you squeeze it with your fist.

.

This gives 810 kilowatts of heat and 0.045 kg/s of boria glass.

That is 25 cubic centimetres per second,

about the rate a toothpaste tube will give if you squeeze it with your fist.

If the molding machinery forms the oxide into balls 4 cm in diameter,

33.5 cubic centimetres in volume,

its maximum production rate is one every 1.35 seconds.

When the car is going along at a constant highway speed,

this slackens to one every 10 or 15 seconds.

These glass forms must be cooled and put in a storage bin to await recycling.

Internal Boron Combustion Engine Considerations

Internal Boron Combustion Engine Considerations

The very high temperature of the boron-oxygen flame makes it very luminous.

Rather than letting the light fly all the way to the combustion chamber walls,

it will probably be beneficial if the motor

quickly causes the energy to be transferred to the working fluid.

This might happen through the fluid's absorbing the light,

or through its being promptly mixed with the flame,

taking the energy by thermal conduction before it can be emitted as light.

This light might work out as a good thing

if its fast flight allows fast energy transfer .

However, it's hard to see how the working fluid could be dark enough.

.

However, it's hard to see how the working fluid could be dark enough.

The thermodynamic cycle now envisioned is a nearly closed one.

Pure oxygen and boron are injected, and pure boria is drawn off.

This means oxygen must be separated from air.

A filter using hot metallic silver seems like one possible way to do this.

Under pure oxygen at one bar, 0.1 MPa, of pressure

20 volumes of oxygen can be taken up by one volume of liquid silver.

Oxygen-laden liquid silver spits as it freezes

because the solid can't accommodate as much.

But it still takes a lot,

as is illustrated by the phenomenon of "firescale" in copper-silver alloys.

When they are heated in air,

oxygen finds its way through the silver to oxidize copper far below the surface,

and the copper oxide heaves up bumps in that surface.

Oxygen must not only go into silver but be forced through it with a pressure gradient.

This silver filtration will take power,

more research is needed to determine exactly how much,

but oxygen purification,

by this means or some better one,

is essential to an internal boron combustion motor.

Why only pure oxygen will do

If the oxygen is pure, boron burns better.

In air it may be practically unignitable,

in the sense that even if you run a large electrical current through a boron bar,

and keep it so hot that air eats away at it and eventually through it,

you end up putting more heat in with the electricity

than comes from the burning.

Once the circuit is broken,

the rate of oxidation is not sufficient to keep the two parts hot,

so the fire goes out.

If that is true, then a higher grade of oxygen -- air is only 21 percent --

is essential for that reason alone.

But does the grade have to be in the high 990s per thousand,

as a silver filter provides?

Boron must burn a little more readily in 99.x percent oxygen than in 70 percent,

but if 70 percent is enough for the flame to sustain itself,

isn't that good enough?

No.

Given that a filter is necessary in the first place,

there is a compelling reason to make it a good one:

with pure oxygen going in, no gas needs to come out.

All the gas that enters the combustion chamber combines with boron

to form a dense liquid.

Suppose the oxygen were cut with several parts in 20 of an inert gas, e.g. neon.

An exhaust gas port would have to exist so this neon could get out again.

Since it and any oxygen left over from the flame are both gases and not separable,

oxygen would have to be let go with it.

0.0216 kg boron combines with 0.048 kg oxygen to yield 0.0696 kg boria,

but to make this happen, maybe twice as much oxygen, 0.096 kg,

would have to be pumped in, and half of it would blow out again.

Although by the time the gases reached the exhaust port

most boria would have fallen out,

some would still be gas-borne and would go out with the oxygen and neon.

Thus we would have nonzero emissions.

Much heat would also go out the port.

In sum, several kinds of waste would result:

waste of oxygen, waste of heat, waste of boron.

Plus the extra complexity of needing a gaseous exhaust port in the combustion chamber,

in addition to the other exit that lets liquid boria out.

For these several reasons,

if we lived on a planet whose air was 79 percent neon, 21 percent oxygen,

we would exclude the neon from our boron-burning motors.

But nitrogen is the main diluent of the oxygen we breathe, not neon,

and in a hot flame nitrogen is not inert.

A small amount will combine endothermically with oxygen,

stealing combustion energy and making gaseous oxides of nitrogen.

These are noxious pollutants,

as suggested by their generic chemical formula, NOx.

Nitrogen exclusion as a side benefit

Nitrogen in a combustion chamber is a real nuisance,

but in a boron combustion chamber the same purification of the oxygen supply

that would be correct design on any planet covered in dilute oxygen

eliminates the nitrogen problem on this, our actual one .

.

The working fluid is expected to be more of this same atmospherically extracted oxygen,

making doubtful the idea of pigmentation to aid absorption of boron-oxygen flame light.

What coloured gas or vapour will stay with the high-pressure oxygen

through very high temperatures and lower ones, and not lose its colour?

But if there is such a pigment,

its use will be a little easier if the same oxygen is used again.

The pigment won't escape, or at least no more of it than will dissolve in the boria.

Finally, a closed cycle allows the use of a recuperator

and so increases heat-to-work conversion efficiency.

The Outside-In Turbine

Centrifugal force field strength is zero at the axis of rotation,

and therefore a turbine that combines its power conversion function

with centrifugal separation of liquid boria from gaseous working fluid

will have no control over oxide that adheres to surfaces there.

It might cause a rotor imbalance.

A peripherally borne rotor may be a solution.

This is an inside-out turbine rotor

whose centrifugal weight is borne by tension in a hoop.

Rather than hanging outward in tension

the turbine blades are supported at their outer ends, by the hoop,

and reach in towards the axis.

They bear their own centrifugal weight as a compressive load,

plus bending load from the fluid.

They don't reach all the way in.

There is a clear channel down the middle.

Where boria could stick to unaccelerated surfaces, there are no surfaces.

This is different from the usual turbine practice

of having the outer ends of the blades clear the housing by a small but safe margin.

Fluid in that margin is affected partly by neighboring fluid that does not miss the blades,

and partly by the wall.

Here the blades go right to the wall, and are part of it.

It is at their other ends that the fluid can go by out of reach.

The unswept region is a circle of small radius

rather than an annulus of large and nearly equal inner and outer radii.

Plus it is bounded only by blade tips.

Turbine motors have continuous combustion but it's also conceivable

that a boron engine could have pulsed combustion

like the piston-in-cylinder hydrocarbon engines we have today.

A boron diesel engine -- ignition by compression --

could have an exceedingly high compression ratio

because even in highly compressed pure oxygen boron won't ignite

until the oxygen is very hot.

However, experiment reveals

that even at bright red heat boria still is a stiff fluid.

At temperatures below the melting point of iron

it is unlikely to be a good lubricant,

and the cylinder walls are a large unaccelerated surface it would stick to.

There it would impede the sliding motion of the piston.

So an annular turbine rotor still is the best of the ideas so far seen.

Boron the Wieldy

Boron the Wieldy

Pure boron is easy to handle .

Combination with oxygen makes it less wieldy,

mainly because the oxygen-to-boron mass ratio is 2.22.

.

Combination with oxygen makes it less wieldy,

mainly because the oxygen-to-boron mass ratio is 2.22.

The resulting colourless clear glass is also not as perfectly water-resistant as boron.

Pure boria probably does not occur in Nature,

for when liquid water gets at it they unite as boric acid.

This does have limited occurrence as the mineral sassolite.

The lightness and wieldiness of dry boria is key to a scheme

where a solar power plant sitting motionless on one side of the Earth

can power many fast-moving vehicles on another.

What it would do is separate boria into boron and oxygen.

One method is proposed in the section titled Boron Decombustion.

Equally many cars might derive the same total propulsion power

if the plant made some other fuel for them,

but then it would have to be bigger.

One reason is that no matter how boria is broken up,

it takes much energy,

more per kilogram than for most other compounds.

An energetic point of view

Otherwise said,

a given quantity of energy will break up a lesser mass of boria

than it would of most things.

If this relatively small mass is hauled across the face of the Earth and then split,

the ratio of transport energy to separation energy will also be smaller than

it would be for most other compounds.

When boria is split the oxygen becomes gaseous,

as it is in air,

and the boron becomes a dark brittle crystalline solid.

This hard, inert, insoluble substance

very effectively stores much of the energy it took to make.

Being just 31 percent as massive as the oxide it came from,

it can return to the point of energy demand at the cost of

somewhat less shipping energy than it took coming in.

Unfortunately not 69 percent less,

not if it returns in the same carrier.

With some difficulty it can be burnt there.

This, it turns out,

yields much more energy than was taken by transport both ways.

Boron is an efficient energy carrier.

Cars that burn it can be efficient indirect nukemobiles

if the energy it carries originates in a nuclear reactor.

How Efficient? A Saltwater Example

If a large modern marine bulk carrier were boron-fuelled,

and had 1,900 tonnes of it on board,

it could stop at a cold Northern city in December

and take on 310,000 tonnes of boria.

It could take this load 10,000 kilometres to a solar boron plant near the Equator.

There it would exchange all its boria, 322 kilotonnes of it,

for 100,000 tonnes of boron.

(What kind of cars would this plant feed? Indirect solmobiles? Star-cars?)

100 kilotonnes is only 31 percent the tonnage it can carry.

Why wouldn't it load all the way up?

Because then it would need 2.22 sister boats

to help it bring all the boria back.

Or let 69 percent of it not return, but that would be very uneconomic.

Next run after that, eleven vessels.

At some point, to stay on top of the job,

every carrier must take away only as much boron as it will be able to bring back.

Taking this light load back to the Northern city it would burn only 1,700 tonnes.

Retaining 1,900 tonnes for its next trip South, it would deliver 96,400 tonnes.

Don't Oil Tankers Beat 96.4 Percent?

Yes.

Travelling the same 10,000 km

an oil tanker as big and efficient as the ship discussed above

would take no payload to an oil well and bring 2.5 times more energy away.

Since its propulsion energy use would be the same,

its energy transfer efficiency is 98.5 percent, not 96.4.

Trying for lower loss in long-range chemical power transmission

than boron can give

one finds the loss fraction resisting like a live thing,

surreptitiously reappearing in other forms,

often much bigger than before.

Even though the petroleum scheme is in large scale practice,

this doesn't mean no such problems can be identified.

Some are mentioned below.

Boron unable to walk on water

Unlike oil, it can't even lie there.

The particular variety of harm associated with oil and oceans is the oil slick.

There never will be a boron slick, nor a boria one.

If spilled they both would lie inert on the bottom.

Boria would dissolve slowly.

The existence of thousands of cubic miles of boric acid already in the sea

suggests no harm would come of this .

.

Boron wouldn't dissolve at all.

Risk reduction

Boron's transport in place of petroleum will yield a very substantial one.

Hydrocarbon tanker ships haven't been free of cargo-fed fires and explosions,

e.g. the Betelgeuse at Bantry Bay in 1979,

and ships carrying boron will be.

The difficulty of setting boron on fire is elaborated on in Boron the Unignitable.

Briefly stated, you can't light the stuff with a blowtorch.

This is a difficulty only in those few centimetres of a boron atom's round trip

that lie within a combustion chamber.

Everywhere else it's a powerful advantage.

Please stand by

A sustainable 31 percent boron load has only 40 percent the energy of a full oil load.

So if a ship can be assigned to move one of either load each month,

it will be hugely more productive with oil.

But some oil well operators in recent years have adopted a practice of

gradually increasing the time a ship must wait to get filled.

In theory this trend will continue .

When this delay raises the round trip time on an oil run

to 2.5 times what it is on a boron run,

it will no longer make sense to stop at the oil well.

Maybe before if the other problems are counted.

.

When this delay raises the round trip time on an oil run

to 2.5 times what it is on a boron run,

it will no longer make sense to stop at the oil well.

Maybe before if the other problems are counted.

Why Would the Solar Plant Not Just Make Oil?

Or maybe not exactly oil, but a solid hydrocarbon polymer

that would combine boron-like ignition resistance and harmlessness if spilled

with oil's advantage of 98.5 percent transmission efficiency over 10,000 km.

Perhaps this will happen to some extent,

but the carrier isn't bringing the necessary carbon dioxide.

If it were, it could only take away a 32 percent load of plastic fuel,

more than boron's 31 percent but not enough more to compensate for the lower energy content.

So like any returning hydrocarbon carrier, it has no payload.

The solar plant must be getting its carbon dioxide locally.

The world is full of limestone, so that's certainly possible.

But carbon dioxide from limestone has an energy cost

that is not compensated by any energy yield at the consuming end.

Instead that energy would come out near the plant,

when dispersed quicklime would take carbon dioxide out of the local air,

making the scheme carbon neutral overall.

This cost is like a transmission loss of roughly seven percent

except it doesn't vary with distance.

Where the boron carrier transmits 96.4 percent over 10,000 km,

the sustainable hydrocarbon carrier transmits 98.5 percent of 93 percent,

result, 92 percent.

As is true for most if not all boron substitutes,

this one requires a bigger solar plant at the Equator than boron would

to support a given load in the world's Northern parts.

Hydrogen at Sea

Hydrogen as fuel is lighter than petroleum,

lighter even than boron,

and has a nonreturning oxide.

Water vapour can be dumped anywhere

and hydrogen generating plants can find new water to split,

or at least different water, almost anywhere.

Hydrogen isn't explosion-proof like boron,

but it must beat hydrocarbons and boron in the efficiency race, must it not?

Actually it comes dead last.

Liquefaction energy is the culprit,

and it's not a seven percent loss, it's about half.

A boron carrier could go around the world the long way and

still beat a hydrogen carrier.

So could a carrier of plastic made from air, water, and solar energy.

Below are footnotes that are linked to by preceding sections.

The main introduction is above,

as is the title screen.

readers since 14 May 1999

according to the free Web-Counter. readers since 14 May 1999

according to the free Web-Counter.

(http://www.digits.com)

|

Use this ad-supported service to guide alternative fuel-interested

e-friends and colleagues here. Those not fond of ads may of course just

send the URL by hand. to guide alternative fuel-interested

e-friends and colleagues here. Those not fond of ads may of course just

send the URL by hand.

|

Main text ends, footnotes begin

Return to mass and volume table

The very large volume for ash from liquid hydrocarbon,

over 100 cubic metres,

is mostly due to gaseous carbon dioxide.

The calculation is based on its density at zero Celsius, 0.001977 kg/L.

If the problem of

where hydrocarbon for many billions of cars will come from in the first place is solved,

the release by those cars of many billions of tonnes of this gas

presents another difficulty. It seems likely to have global consequences.

But its release has immediate local consequences that we seldom think about.

We are very accustomed to hydrocarbon-derived limits on our thinking about cars,

limits that hydrogen- or boron-burning cars do not impose.

(Other limits still exist, of which more will be said a little later.)

What if everyone in a crowded shopping mall remained in his or her car?

Not as many people could fit, evidently, but maybe these are very small cars.

If they burn boron they don't pollute the indoor environment at all.

If they burn pure hydrogen

the mall's air conditioning may need to dehumidify the air.

This situation doesn't arise with today's carbon-burning cars

because everyone in the mall would get very short of breath,

and flee or die of suffocation,

long before anyone would be bothered by humidity.

This is true regardless of how well tuned and clean burning the hydrocarbon cars are,

because carbon dioxide is the cause of the trouble.

This chemical is also naturally produced by human life processes,

and we absolutely need to get rid of it.

If there is too much in the air,

so that blood carbon dioxide has no concentration downgrade to escape along,

it doesn't matter how much oxygen there is.

If a hydrocarbon combustor in perfect working order,

that just means all of the carbon it is exhausting is in the form of dioxide.

Malfunctioning cars can emit carbon monoxide, a strong poison,

but that is not the main reason why today's cars can't come in the house.

If they could, would that a good thing?

Difficult to say, what with thinking limited by existing structures,

but if we try it for 20 years or so and then consider going back,

maybe some benefits will come to mind,

or indeed maybe no benefit will have turned up and the cars,

after a brief foray,

will have returned to their almost exclusively outdoor habits.

An Insidious Hazard of Carbon-Free Combustibles

If one tries to keep a submarine warm with a charcoal fire,

and the carbon dioxide

that would otherwise be an immediate hazard

is made harmless by being captured in alkali,

eventually there will be a shortage of oxygen.

This is the above mentioned limit that exists

even when combustion is carbon free.

Infringing on it is dangerous

because animals don't naturally detect oxygen-deficient air the way they do carbon dioxide excess.

This hazard is a remote one

because consuming all or most of the oxygen in an enclosed space produces a huge amount of heat,

and it would be very unusual for the enclosure to be able to lose the heat

without also exchanging the oxygen-depleted air for fresh.

E.g. consider a house trailer sized room 2.5 metres by three metres by five metres.

It contains 45 kilograms of air and 10 kg oxygen at sea level.

In the depth of winter someone is heating it from inside by burning a carbon-free fuel,

and the outside is so cold and the trailer is so thermally leaky

that it takes 10 kW of heat to keep it warm.

The trailer's occupant gets 17.87 megajoules per kilogram of oxygen

if he combines it with hydrogen,

so a hydrogen burner will take half the oxygen in 2.5 hours.

The unlikely thing, unless the trailer really is hitched to a submarine,

is that it could leak all that heat without being well ventilated.

In fact this trailer would be unsafe in the summer too,

because just breathing in it would raise the carbon dioxide concentration from 0.03 percent to 0.2 percent in 2.5 hours.

When oxygen is combined with boron

the heat yield per kilogram of oxygen is 26.53 MJ

so in that case, for a 50 percent depletion to exist,

the trailer must still be on the same air after 3.7 hours.

An Oxygen Extractor that Quits before You Do?

It's possible that boron's unignitable nature will make a total

difference, and make that slight extra time irrelevant.

While hydrogen can be ignited very easily,

even in air with low oxygen,

a designed system is needed to ignite boron.

Part of the necessary commitment is extracting pure oxygen from air.

Air gives up oxygen not directly to a boron flame,

but to an oxygen extractor, and if that device can be so made

that it will take plenty of oxygen when there is plenty,

and none at all if the oxygen concentration is getting down anywhere near a level

that would inconvenience air-breathing life,

then dealing with the anoxia hazard will have been folded into a design task

that had to be done anyway.

Return to mass and volume table

|