|

Meeting The Challenges of Zoning in the Information Age: Planning For Wireless Communications Facilities |  |

|

Meeting The Challenges of Zoning in the Information Age: Planning For Wireless Communications Facilities |  |

Although the issue of siting wireless communications facilities is a recent phenomenon, several communities around the country have regulations dealing with these issues. This section will examine several communities' ordinances, their language and examining how well they deal with facility siting, as well as determining their compliance with the Telecommunications Act of 1996.

For use in the analysis of these existing ordinances, I have taken what I believe to be the eight most important aspects of a wireless facility ordinance are developed for comparison. These criteria will be examined for each ordinance reviewed, and will then be compared to the model ordinance developed in Chapter 5 of this project. A summary of the ordinances examined for this project follows in the tables presented in the following table.

| Date Adopted | Last Amended | Type of Ordinance | Definitions | Application Requirements | Co-Location Provisions | Safety Considerations | Aesthetics | Lighting | Abandonment | |

| Jefferson County, Colorado | 1985 | 1993 | Zoning Amendment | In a separate Wireless plan | Yes | Not Required, but suggested | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Cincinnati, Ohio | N/A | N/A | Zoning Amendment | Yes (One definition) | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| Gaithersberg, Maryland | 1990 | N/A | Zoning Amendment | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Portland, Oregon | 1991 | N/A | Zoning Amendment | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

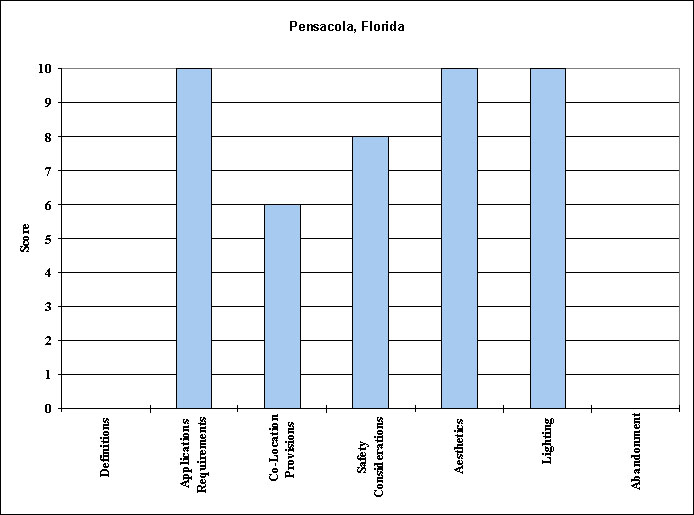

| Pensacola, Florida | 1994 | N/A | Zoning Amendment | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No |

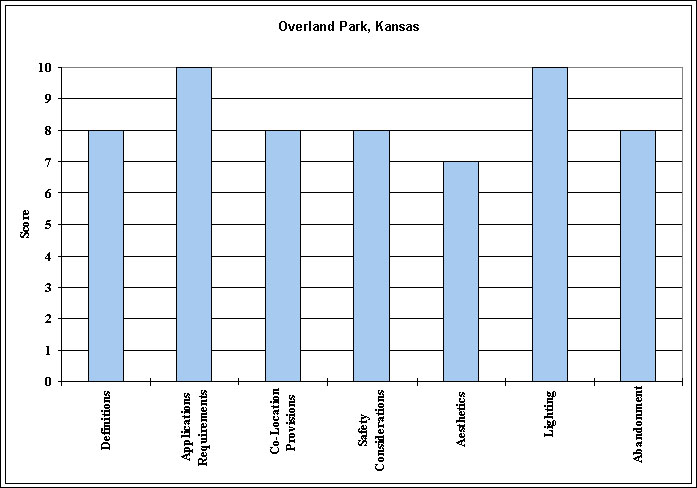

| Overland Park, Kansas | 1996 | N/A | Stand-Alone | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

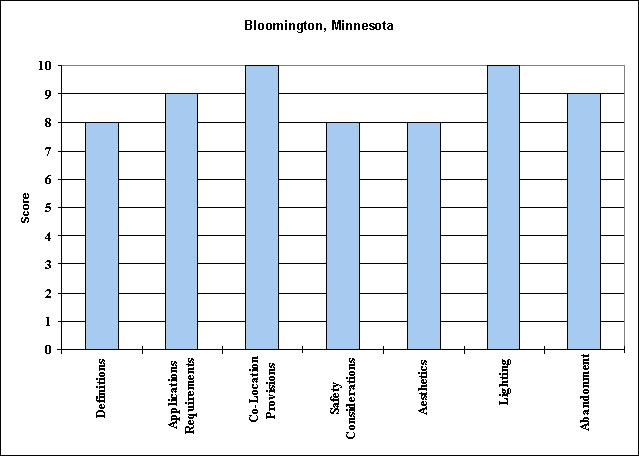

| Bloomington, Minnesota | 1996 | N/A | Zoning Amendment | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

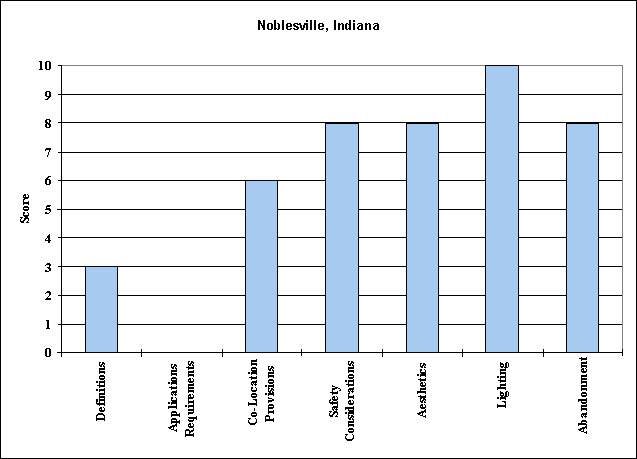

| Noblesville, Indiana | 1997 | N/A | Zoning Amendment | Yes (One definition) | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

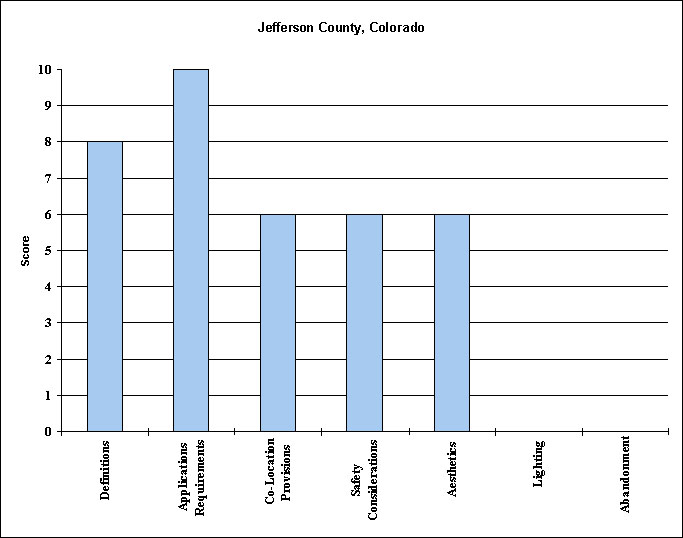

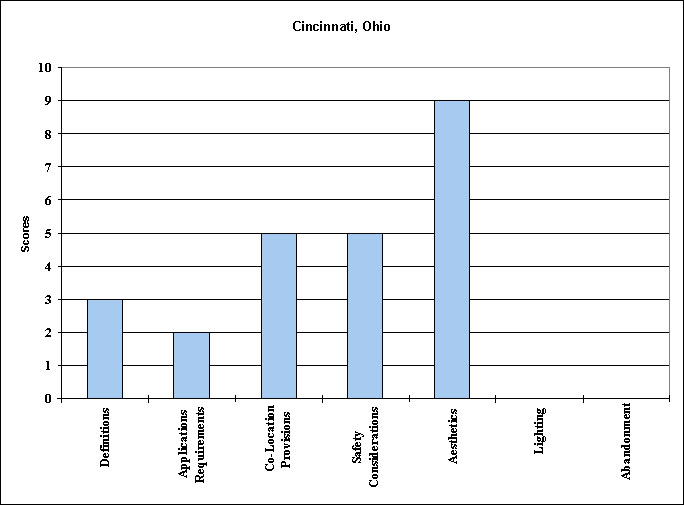

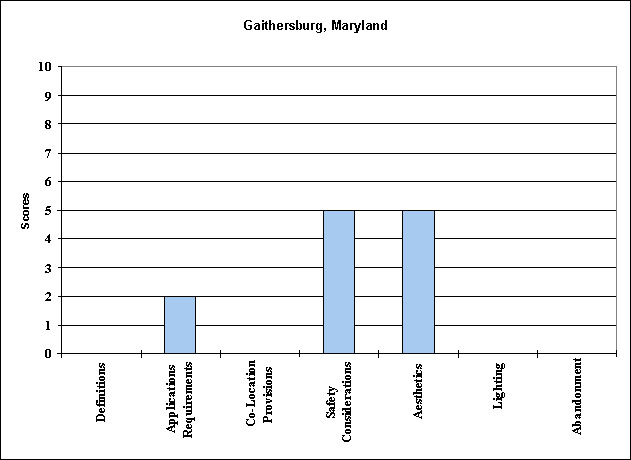

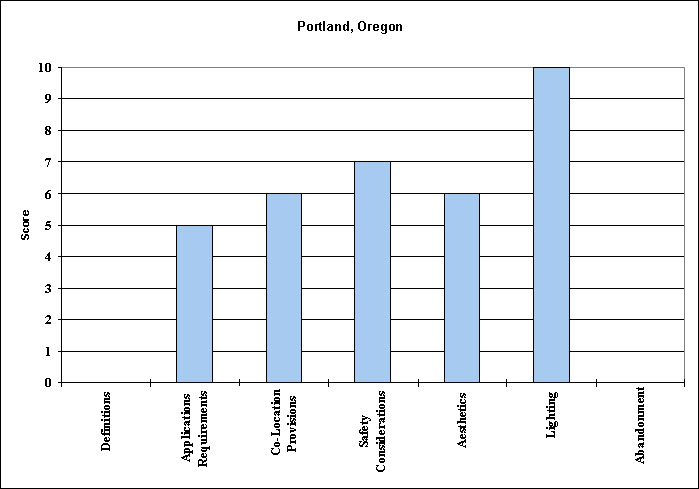

In addition to a general comparison of each ordinance, ordinances will be rated individually, based on how well the ordinance meets each of the eight characteristics (type of regulation does not apply in this analysis), used in my analysis. A score of zero to ten (zero being poorly conceived or written, ten being extremely thorough or well conceived), can be achieved in each category. Using past experience with the subject of wireless regulation, as well as the "Key Elements to a Wireless Ordinance" section of the National League of Cities Siting Cellular Towers report (1997), the basis for these ratings is how well they deal with the issues of community aesthetics, safety, compliance with the Telecommunications Act of 1996, and provision of adequate service to customers of wireless services.

Jefferson County, CO, has been dealing with wireless facilities since

1985, the oldest set of regulations that have been researched for this

project (the regulations were amended in 1993).

Jefferson County's regulations are in the form of a zoning amendment, but go a step further than most communities. Jefferson County also has a Telecommunications Plan that is part of the county's master plan. All definitions related to wireless facilities are located in this plan, and there is language in the zoning ordinance that makes it very clear that "accordance with the general plan" is an important aspect of any application for a wireless facility siting.

The strengths of the Jefferson County regulations are the applications procedures and the coordination with planning efforts. The ordinance does have language dealing with everything except lighting from my list of eight criteria (although co-location is not required by the ordinance, providers must clearly demonstrate that they have sought to co-locate), but much of the language is not specific enough, or is geared towards high-emission uses, such as radio and television transmission.

The ordinance lacks treatment of mobile communications antennas and towers. There are well conceived and thorough procedures in which standards must be met for the emissions of electromagnetic radiation. This is a problem, however, since in Section 704 of the Telecommunications act of 1996, local governments cannot base approval of a proposed wireless facility on electromagnetic emissions, so long as they meet the guidelines set by the FCC.

Jefferson County, due to the age of the original ordinance and amendments, needs to update the language of the ordinance so that it, 1) does a better job of examining cellular, PCS, and ESMR antennas, and 2) revises the emissions section, bringing it up to compliance with the Telecommunications Act of 1996.

Cincinnati uses language within its zoning ordinance to regulate cellular towers. Cellular towers are included in the definition of "public utility distribution system" along with other elements including, "facilities for the transmission or distribution of gas, electricity, steam, water, or communications, but not including a public utility station" (Cincinnati Zoning Ordinance, from PAS Report, 1995). Public utility distribution systems are allowed as both conditional uses and as permitted uses, depending on the zone you are talking about. From what can be ascertained from the excerpt (the zone definitions were not included), they are a conditional use in most residential zones, and a permitted use in most commercial or industrial zones.

The ordinance goes further to say that a "communication distribution system antennae installed on a monopole structure of less than 150 feet in height" is a permitted use in high density residential zones (again, this is from inference), business/residential zones, and industrial zones. It must go through a conditional use hearing process in any other zone where it is not a use by right, but listed as a conditional use. The hearing process assesses whether or not the location would be in the best public interest. The hearing process includes issues such as possibilities of sharing use on an existing tower, minimum setback and yard standards, aesthetics and architectural compatibility with the surrounding area, screening, and landscaping.

Cincinnati also has a very well designed method to deal with facility abandonment. The owner of the tower would also be required to annually file a declaration of his or her intent for continuing the operation and use of the tower, and obsolete facilities will be removed by the city within 12 months of ceasing operation.

Gaithersburg's zoning amendments from 1990 are in much the same situation as the Jefferson County regulations are; they are geared towards television and radio towers and antennas, and do not deal specifically enough with cellular, PCS, and ESMR. Unlike the other ordinances reviewed in this project, however, there is not enough specificity in its language.

Gaithersburg's regulations go no further than stipulating that towers and antennas are allowed in the C-2 (General Commercial) zone, so long as they are not a danger to the health, safety, and general welfare of its residents. There are no requirements for co-location, lighting or abandonment, nor are there any definitions given for the terms used in the ordinance. The language of this ordinance leaves too much unresolved, probably because it was written prior to the boom in mobile communications and the Telecommunications Act of 1996.

Portland's zoning amendments are well conceived, even though they were written prior to the Telecommunications Act of 1996. Written in 1991, Portland covers several of the key criteria, most prominently provisions for co-location, and are the oldest regulations reviewed that deal with the issue of lighting. Portland also does a nice job of specifying what types of facilities are exempt from regulation.

Portland finds itself, however, in the same boat as Jefferson County, CO, in that it bases much of its approval standards based on electromagnetic emissions, which, as has been stated previously, is not a valid reason for denying an application under Section 704 of the telecommunications Act of 1996. Other weaknesses of Portland's regulations are the lack of definitions, and no language dealing with the abandonment of towers and antennas.

Within the supplementary district requirements of Pensacola's zoning ordinance, there is a section on "commercial communications tower review." Towers are allowed in several districts, but are subject to site plan review in every case. There are also well conceived aesthetics protections in the ordinance for governmental districts, as well as historic districts (towers may be allowed, but only rooftop towers that clear architectural compatibility review).

Pensacola's strengths are in the very clear applications requirements, the concern for aesthetics, and the safety precautions that are incorporated into the specific site design requirements. The main drawbacks to the ordinance are the lack of definitions and facility abandonment regulations.

The lone stand-alone wireless facilities ordinance reviewed for this project is Overland Park. This set of regulations (along with Bloomington, Minnesota's) came up with the most consistent set of scores in all of the criteria areas.

Overland Park starts out with clear statements of purpose, a relatively good set of definitions, and requirements specific to each zoning district where facilities are allowed. Overland Park's applications requirements are very thorough and clearly defined. Co-location is required, and single user towers will only be allowed if a series of conditions have been met. Incentives are used to promote co-location as well. Aesthetics and safety are dealt with appropriately, and Overland Park requires the removal of abandoned towers at the tower owner's expense after a set of time periods have been exhausted.

Aside from Overland Park, no other set of regulations scored as high as Bloomington's zoning ordinance amendments (full text of Bloomington's Ordinance is in Appendix 3).

While Bloomington is strong in all of the criteria, its strongest point is its co-location requirements. Bloomington, like most regulations with co-location provisions, requires proof that the applicant has looked for an existing structure to locate on, but takes it a step further. "A proposal for a new commercial wireless telecommunication service tower shall not be approved unless the City Council finds that the telecommunications equipment planned for the proposed tower cannot be accommodated on an existing or approved tower or building within a one mile search radius (one half mile search radius for towers under 120 feet in height, one quarter mile search radius for towers under 80 feet in height) of the proposed tower" (Bloomington, MN, 1996). If these requirements are proven, then Bloomington requires the construction of all new towers to be designed so that it can accommodate at least 2 additional users if the tower is over 100 feet, or one additional user if the tower is between 60-100 feet tall.

Bloomington covers all of the criteria for review quite well. It is not, however, without its weaker points. A drawback to the ordinance is the lack of towers as a permitted "use by right" in any of the zoning districts. The ordinance might be better served by allowing facilities in Industrial and highway districts, and leaving the rest of its zones where facilities are allowed as conditional uses the way they are written.

Noblesville is the most recent ordinance reviewed here, passed by the city council on March 2, 1997. This zoning amendment nicely covers the most important aspects of regulating wireless facilities in a concise, short set of regulations. The drawbacks to Noblesville's amendments are the lack of applications requirements, and a limited definitions section (only one definition).

Noblesville is also the first ordinance reviewed that allows wireless facilities as a permitted use in some of its zoning districts (Heavy Industrial, and Extractive Industrial). The ordinance also requires that wireless service providers submit a plan for their future plans in Noblesville, so that officials can determine what potential sites may be applied for in the future.

Though I have not reviewed Sacramento County's ordinance, the APA-PAS reference packet includes an interdepartmental memo from the Sacramento County Planning Department concerning the need to update the zoning ordinance to address the issues of "cellular phone system facilities."

The planners, in the memo, outlined a table of recommended siting criteria for each of the various elements in setting up a cellular communications network. This table would be based upon the planning department's perceptions of the thresholds of public acceptance of the visual components of a cellular system, not on the technical requirements of the system. The goal was to integrate these elements as well as possible into the existing land use patterns of the county.

The table itself would then be used as a performance-based tool to possibly eliminate a large portion of the permitting process. If a facility were to meet all of the criteria stated in the table, there would be no need for public hearings for construction to commence. However, if any of the criteria were not met, then the project would have to go through the standard permitting process with public hearings included.

This use of performance criteria has been replicated in this project, as it is a method of creating incentives for wireless facility sitings in areas most suitable (for the impact on the community's interests) while providing a means for the service provider to move quickly through the permitting process and begin service to its customers.