L'IMPEDENZA

Abbiamo detto che gli elettroni possono essere spinti

da un generatore in un circuito per essere incanalati e

utilizzati ma tramite che cosa? Tramite dei conduttori di

materiale opportuno. In effetti non tutti i materiali

possono condurre l'elettricità allo stesso modo: in

genere tutti i metalli permettono il passaggio agli

elettroni mentre gli altri materiali (come mica, ambra,

vetro, carta, legno, bachelite, acqua distillata, aria

secca e materiali plastici in genere) non lo permettono.

A loro volta i metalli offrono tutti (quale più, quale

meno) una certa resistenza ,

paragonabile all'attrito in meccanica, al passaggio degli

elettroni. I materiali in grado di condurre, sia pure con

resistenza, la corrente elettrica nei due sensi (cioè

dal - al + e viceversa) si chiamano conduttori,

viceversa: isolanti. Esistono poi (ma qui

lo accenniamo soltanto) dei materiali, come il silicio e

il germanio, i quali conducono la corrente in un senso

solo (esempio dal + al - e non viceversa) e sono

denominati semiconduttori. Se la corrente

che circola nei conduttori è alternata, possono

verificarsi dei fenomeni di sfasamento tra ddp e corrente

(lo accenniamo qui solo per completezza) e anche questo

costituisce un ostacolo al passaggio della corrente.

L'insieme di tutti questi impedimenti (cioè resistenza e

gli altri fenomeni) viene denominato impedenza. Va

da sé che in corrente continua ,dove non esistono

sfasamenti, impedenza e resistenza

sono la stessa cosa. L'impedenza ha per simbolo Z mentre

la resistenza pura ha per simbolo R .

Entrambe si misurano in OHM (simbolo: W:lettera greca che si

legge: omega). Immaginiamo il nostro conduttore come un

tubo dove il nostro generatore spinge gli elettroni a

gran velocità (300000 km al secondo). Se il tubo è

largo ,liscio e non troppo lungo, gli elettroni

giungeranno a destinazione in buone condizioni, ma se

invece è stretto,pieno di strozzature ed asperità ed

esageratamente lungo i poveri elettroni faticheranno

parecchio per arrivare stanchi alla méta! Anche il tubo

patirà sollecitazioni che lo riscalderanno, o

addirittura lo danneggeranno! Analogamente se il

conduttore (un cavo elettrico nel nostro caso) ha una

buona area di sezione, un basso coefficiente di

resistività e non è eccessivamente lungo verrà

attraversato facilmente dalla corrente elettrica. Il

coefficiente di resistività ha per simbolo r(lettera greca che si

legge ro) ed è un numero unico per ogni

materiale: quanto più è basso tanto migliore è il

materiale al fine della conduzione. La resistenza (R)

di un conduttore risulta perciò direttamente

proporzionale al coefficiente di resistività (r) ed alla lunghezza (L),

ed inversamente proporzionale alla sezione (S)

secondo la seguente formula:

R= r *

L / S

Dove R è espresso in ohm, L in metri, S in mm2. Questa

è la prima legge di Ohm. A titolo informativo il rame ha

un r di 0.018, superiore a

quello dell'argento (0.017), ma inferiore a quello

dell'oro (0.025), dell'alluminio (0.029), del ferro

(0.10) , del nichel (0.09) , del piombo (0.23).

La resistività, con qualche eccezione, cresce nei

materiali con l'aumento della temperatura.. Il fenomeno

per cui si sviluppa calore in un conduttore al passaggio

degli elettroni si chiama effetto joule. Abbiamo visto

l'altra volta i parametri propri del passaggio degli

elettroni in un conduttore:

- la differenza di potenziale, che d'ora in poi

chiameremo tensione (voltaggio per alcuni)

,si indica con V, si misura in Volt e può

variare.

- L'intensità di corrente (o più brevemente

corrente); si indica con I, si misura in Ampere (A)

e può variare.

- La resistenza (che in c.c. coincide con

l'impedenza Z) si indica con R, si

misura in Ohm (W)

ed essendo legata alle caratteristiche fisiche

del materiale conduttore non può variare.

La seconda legge di Ohm lega tra loro questi tre

parametri secondo le seguenti formule:

V=RI; I = V/R; R = V/I

Questa legge ci consente, noti due parametri, di

ottenere il terzo; consente inoltre di dire:

- la corrente aumenta quando la tensione aumenta e

diminuisce quando anche la tensione diminuisce :

(I=V/R)

- La corrente, passando in un conduttore di

determinata resistenza, genera in esso una caduta

di tensione (cioè una d.d.p. ai capi di questo

conduttore) direttamente proporzionale alla

resistenza ed alla corrente (V =RI)

- Questo spiega perché i cavi di una batteria di

auto, dove la tensione é bassa (12 volt) e la

corrente notevole (anche 100 ampère

all'avviamento) sono di grossa sezione e

piuttosto corti, mentre gli elettrodotti che

trasportano elettricità a centinaia di

chilometri di distanza, abbiano una tensione

altissima (qualche centinaia di migliaia di volt)

e una corrente ridotta con una sezione dei cavi

che é un compromesso fra bassa resistenza e peso

dei cavi.

- poiché intensità di corrente e tensione sono

direttamente proporzionali, il loro rapporto,

essendo costante, dà il valore della resistenza

del conduttore: R = V/I.

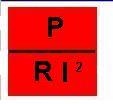

Se ci troviamo nella necessità di calcolare di questi

parametri e non ricordiamo le formule possiamo

memorizzare il seguente schema:

Legge di Ohm

Spostate il mouse sopra le figure per

vedere il funzionamento.

Nascondendo con un dito il parametro

che ci interessa ottenere (beninteso conoscendo gli altri

due), ad esempio la tensione:

Se ci interessa la corrente:

Se ci interessa la resistenza:

Finora abbiamo visto la corrente elettrica mentre attraversa un conduttore generico, senza considerarne a fondo gli effetti né la possibile utilizzazione; orbene gli effetti sono essenzialmente i seguenti:

- Effetto termico: ne abbiamo già accennato parlando della resistenza; è dovuto all'attrito elettrico del mate- riale e consiste nello sviluppo di calore all'interno del conduttore; è detto anche "effetto joule".

- Effetto magnetico: intorno ad un conduttore percorso da corrente appaiono linee di forza analoghe a quelle prodotte da una calamita.

- Effetto chimico: si manifesta quando la corrente passa attraverso una soluzione chimica; le molecole vengono dissociate e gli atomi che compongono le medesime diventano ionizzati , depositandosi sugli elettrodi di segno opposto; il fenomeno è sfruttato in particolare nelle officine di galvanoplastica; è pure sfruttato nel funzionamento di generatori di corrente quali le pile e gli accumulatori, apparati che studieremo presto.

- Effetto fisiologico: interessa soprattutto l'antinfortunistica; la corrente elettrica, specialmente con alte tensioni e intensità, è pericolosa e produce effetti devastanti nel corpo umano. Con differenze che variano da una persona all'altra, la corrente massima sopportabile è di 15 milliampère (0.015A); considerando che in particolari condizioni, la resistenza da una mano all'altra può essere di circa 10.000 ohm, la tensione mortale può essere, applicando la legge di Ohm (V=RI): 10.000* 0.015= 150V, tensione abbastanza comune nella vita di ogni giorno. E' da notare che negli amplificatori lineari a valvole, alla portata di ogni radioamatore, si raggiungono tensioni ben superiori a 2000 V! Ovviamente la fatalità della scarica dipende dalla zona attraversata: da una mano all'altra passa per il cuore, provocandone la fibrillazione. Se il corpo è bagnato o le mani sono sudate, la resistenza scende di parecchio ed in tal caso anche le tensioni domestiche possono diventare pericolose. Inoltre la corrente elettrica risale attraverso i liquidi che scorrono: si è verificata in passato la tragica morte di un bambino il quale, dall'alto di un viadotto della ferrovia, orinò per gioco sui cavi sottostanti. In ogni caso, anche se non è sempre mortale, la corrente elettrica provoca sempre dolorose scosse o profonde ustioni e deve quindi essere trattata con rispetto……

Per generare tutti questi effetti (fisiologico a parte!) occorre che la corrente elettrica passi attraverso particolari componenti, ideati apposta per esaltare e sfruttare un particolare effetto; tali componenti sono collegati per mezzo di fili elettrici (detti anche cavi quando sono di grandi dimensioni) ad un generatore.

Fra questi componenti esamineremo ora:

- Il resistore: è composto di materiale ad alta resistività (nichelcromo, costantana, grafite, impasto di carbone, leghe speciali). Il corpo è generalmente un cilindro ceramico, sul quale è avvolto del filo metallico (per i resistori a filo) oppure è depositato l'impasto resistivo (per i resistori ad impasto); ai capi del cilindro, collegati al materiale resistivo, sono disposti due corti spezzoni di filo, detti reofori. Il resistore concentra in sé il fenomeno già esaminato della resistenza elettrica; sfrutta l'effetto termico (o effetto Joule)

Il simbolo del resistore è il seguente:

Il resistore si comporta allo stesso modo in corrente continua o alternata e dissipa sempre energia.

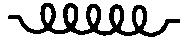

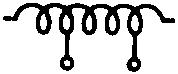

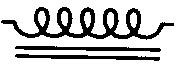

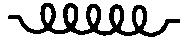

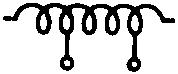

- L'induttore: è composto normalmente di filo elettrico avvolto a bobina, con o senza supporto a seconda della rigidità del filo; ha due capi detti anch'essi reofori (se ne ha di più, vengono detti prese intermedie) e un numero più o meno grande di spire. Esalta e sfrutta l'effetto magnetico, in modo molto più accentuato se munito di nucleo ferroso.

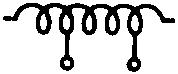

Il simbolo dell'induttore è il seguente:

Con prese intermedie

Con nucleo

L'induttore ha un comportamento differente in corrente continua e in corrente alternata, che esamineremo in dettaglio quando studieremo a fondo il componente; in corrente continua non ne ostacola il passaggio se non per il valore resistivo del filo di cui è composto l'induttore stesso; un induttore ideale (inesistente perchè il materiale presenta sempre una sia pur minima resistenza) non dissipa energia elettrica ma la restituisce sotto forma di energia magnetica.

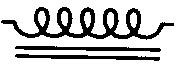

- Il condensatore: è costituito da due piastre affacciate; al centro di ciascuna piastra è saldato un reoforo; tra le piastre esiste uno spazio più o meno largo, il quale può essere vuoto o riempito da materiale isolante (mica, vetro, carta, politene, ceramica o altro); questo spazio è chiamato dielettrico. Quanto più larghe sono le piastre e più sottile il dielettrico, tanto più alta è la capacità del condensatore. La proprietà del condensatore è quella di accumulare cariche elettriche, come avevamo visto fare da parte delle nuvole all'inizio della nostra trattazione; ne accumula tante di più quanto più alta è la sua capacità.

Il simbolo del condensatore è il seguente:

Come già abbiamo visto per l'induttore, anche il condensatore si comporta diversamente in corrente continua e in corrente alternata; possiamo dire che si comporta in maniera opposta rispetto all'induttore: infatti un condensatore ideale (inesistente perché la resistenza del dielettrico non è mai infinita) costituisce un ostacolo totale al passaggio della corrente continua e non dissipa energia.

Vedremo ora come questi elementi si comportano, se inseriti in un circuito elettrico, per ora alimentato con corrente continua, ma prima vogliamo esaminare alcuni elementi ausiliari che: 1) producono la corrente, 2) la misurano, 3) la inseriscono o la escludono:

- Il generatore: simbolo

Questo è un simbolo di generatore generico e non specifica il tipo di corrente generata.

Generatori per sola corrente continua sono la pila e l'accumulatore (o batterie dei medesimi); il loro simbolo è il seguente:

Un particolare generatore di c.c. è l'alimentatore. Più che un generatore è

un apparato che preleva dalla rete la corrente alternata, la raddrizza (cioè esclude la parte negativa della c.a.) e la livella al

valore di cresta (vedremo poi ciò che significa) trasformandola in c.c. E' simboleggiato come una fonte generica di c.c. e cioè

Oppure

Oppure

Tutti i generatori hanno una loro propria resistenza , detta resistenza (o impedenza) interna e di essa bisogna tener conto nel dimensionare il circuito. Quanto più bassa è la resistenza interna, tanto più è efficiente il generatore.

- Gli strumenti di misura, simbolo generico:

Può indicare un voltmetro oppure un amperometro , a seconda della sua disposizione nel circuito,

se invece si vuole essere specifici, occorre usare gli strumenti coi loro appropriati simboli e cioè:

Il Voltmetro, simbolo

Misura la tensione in volt (V) oppure nei suoi multipli (Kv: leggi kilovolt pari a 1000 volt)

o sottomultipli (mV: leggi millivolt pari a 1/1000 volt oppure m

V: leggi microvolt pari a 1/1.000.000 volt).

Il voltmetro è sempre posto in parallelo al circuito da misurare (Vedremo tra poco ciò che significa)

L'Amperometro: simbolo

Misura la corrente in ampère (A), oppure nei suoi sottomultipli (mA: leggi milliampère pari a 1/1000 ampère;m

A: leggi microampère pari a 1/1000.000 A). Esiste poi il picoampère, pari a un miliardesimo di A, misura effettuabile solo con strumenti ultrasensibili,non alla portata del comune radioamatore.

L'amperometro va sempre posto in serie (vedremo in seguito) al circuito da misurare.

- L'interruttore: simbolo =

Serve ad aprire o chiudere un circuito. Se non ci fosse occorrerebbe attaccare o staccare manualmente il carico, operazione ovviamente troppo scomoda; tramite l'interruttore è possibile tenere il carico sempre inserito e attivare o interrompere il flusso della corrente.

Merita un discorso anche il carico, che può essere un motore elettrico: simbolo:

una lampada: simbolo:

un altoparlante:simbolo:

un semplice resistore o altro.

Tutti i carichi hanno una propria impedenza e tutti consumano energia,perciò possono essere indicati semplicemente come un resistore di quella determinata impedenza.

Quando il carico è un resistore puro (o una lampada che poi non è altro che un resistore) tutta l'energia consumata viene trasformata in calore.

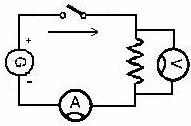

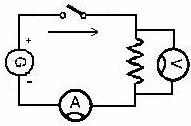

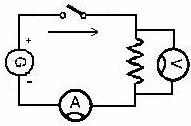

Altri simboli verranno introdotti a mano a mano che impiegheremo i corrispettivi apparati. Ed ecco il più semplice di tutti i circuiti:

Vediamo che è composto da un generatore di corrente continua, da un resistore (ma potrebbe essere un motore, una lampada o un trasmettitore con la stessa impedenza), dai fili che portano la corrente e da un interruttore. In serie al circuito, cioè in una posizione tale per cui la corrente lo possa attraversare c'è un amperometro, mentre in parallelo al circuito, cioè in una posizione che abbraccia i due poli (+e-) c'è un voltmetro. In questo caso ,per comodità, l'abbiamo posto ai capi del resistore, ma potrebbe essere ai capi del generatore o a valle di interruttore e amperometro: la misura non cambierebbe.

Quando l'interruttore viene chiuso, la corrente fluisce nel senso della freccia (senso convenzionale), attraversa il resistore e l'amperometro, tornando al generatore, e così via in un ciclo continuo; gli aghi dei nostri strumenti segnano qualcosa. Supposto che il nostro generatore sia privo di resistenza interna ed eroghi una tensione costante di 1 V e che il nostro resistore abbia un'impedenza di 1W,vediamo che l'amperometro segna 1 A , mentre ovviamente il voltmetro segna 1 V . Infatti, applicando la legge di Ohm: I = V/R, cioè I = 1V/1W= 1 A .

Toccando il resistore, notiamo subito che si scalda, a volte fino a scottare. Infatti gli elettroni, per vincere l'attrito elettrico, devono compiere un lavoro, il quale regolarmente si traduce in calore! L'unità del calore è la caloria e l'unità di lavoro nel sistema Metro , Kilogrammo, Secondo (MKS) è il Joule, pari a 0,24 calorie (di qui l'effetto joule). Il lavoro compiuto durante un'unità di tempo corrisponde ad una Potenza (simbolo P). L'unità di potenza è il Watt; 1 joule al secondo corrisponde ad 1 Watt (simbolo W).

Però anche1V*1 A equivale ad 1W; possiamo enunciare ciò con la seguente formula:

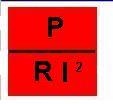

P = VI ma, per la legge di Ohm: V=RI cioè

P=(RI)I, cioè ancora P = RI2 . Inoltre, sempre per la legge di Ohm: I=V/R, perciò P=V(V/R) cioè P = V2/R.

Si hanno quindi tre enunciati per esprimere la potenza:

P =VI ; P = RI2 ; P = V2/R.

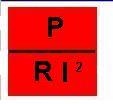

Da ciascun enunciato possiamo ricavare ogni singolo elemento, conoscendo gli altri due.Anche qui possiamo ricorrere al trucco mnemonico già visto con la legge di Ohm, tenendo presente che occorre uno schema per ciascun enunciato e cioè:

Di questi prenderemo in esame soltanto il primo:

Se ci occorre P:

Se ci occorre V:

Se ci occorre I:

Analogamente per gli altri due schemi, tenendo presente che gli elementi come I e V vanno prima elevati al quadrato e, nel caso di risultato, occorre estrarne la radice quadrata.

|

THE IMPEDANCE

We said that electrons can be pushed onto

a circuit to be canalized and utilized, but by what mean

? By mean of conductors of convenient material. Indeed

not all materials can conduct electricity at the same

manner: generally all metals allow transit of electrons,

while other materials (like mica, amber, glass, paper,

wood, bakelite, distilled water, dry air and plastic

material in general) don't permit it. However all metals

offer (more or less) a certain resistance

to the transit of electrons, comparable to attrition of

mechanics. Materials capable of conducting, even if with

resistance, current in both directions (that is from - to

+ and vice versa) are named conductors,

vice versa insulating. There are

however materials (but now we just mention it) like

silicon and germanium, which conduct current in one way

only (e.g. from + to - and not vice versa) and are

named semiconductors. If current

circulating in conductors is alternating, phenomena of

phase-difference between dop and current can occur (we

indicate it here only for completeness) and that form a

obstacle to transit of current as well. The concurrence

of all impediments (i.e. resistance and other phenomena)

is named impedance. Of course in

direct-current, where there aren't any phase-differences,

impedance and resistance

are the same thing. The symbol of impedance is Z

, while the symbol of pure resistance is R;

they are both mesured in OHM

(symbol W: greek letter readed omega). Just

imagine our conductor like a pipe where the generator

pushes electrons at great speed (300000 km /sec). If

the pipe is large, smooth and not too long, the electrons

reach their destination in good condition, while if it's

narrow, full of stranglings and roughnesses and

excessively long, poor electrons will work hard to reach

very tired their goal! The pipe as well will suffer

solicitations which will warm up and perhaps damage it!

In an analog way, if the conductor (a electric cable in

our case) has got a good area of section, a small coefficient

of resistivity and isn't too long, the

electrical current will run through it very easily. The

symbol of the coefficient of resistivity is r (greek letter

readed ro) and is a fixed figure for

each material: the lower it is, the better the material

is for what conduction is concerned. The resistance (R)

of a conductor results therefore directly proportional to

the coefficient of resistivity (r)

, to the lenght (L), and inversely

proportional to the section (S)

according to the following formula:

R= r

* L / S

Where R is expressed in ohm, L in meters,

S in mm2 . This is the first Ohm's law. As an

example, copper has a r of

0.018, more than silver (0.017), but less than gold

(0.025), aluminum (0.029), iron (0.10), nickel (0.09), or

lead (0.23).

The resistivity, with some exception, increases with

the rise of temperature. The phenomenon of heating a

conductor at the transit of electrons is called

"joule effect". We have already seen the

parametres of electrons passing through a conductor:

- The difference of potential, which henceforth

we will name voltage, is indicated with V, is

measured in Volt and can vary.

- The intensity of current (or shortly current) is

indicated with I, is measured in Ampère (A) and can vary.

- The resistance (which in d.c. coincides with the

impedance Z) is indicated with R,

is measured in Ohm (W)

and, being binded to the properties of the phisical

conductor, can't vary.

The second Ohm's law ties this parametres following

this formulas:

V=RI; I = V/R; R = V/I

This law allows, knowing two parametres, to obtain the

third; it allows in addition to say:

- The current increases when the voltage increases

and decreases when the voltage decreases: (I=V/R)

- The current, passing through a conductor of a

certain resistance, generates in it a fall of voltage

(that is a d.o.p. across the tips of this conductor) directly

proportional to the resistance and to the current: (V=RI)

- That explains why the cables of a car-battery,

where the voltage is low (12 volt) and the current high

(even 100 ampère during the start), have a large

section and a small lenght, while the electro-lines,

which transfer electricity to hundreds of miles, have a

very high voltage (some hundreds of thousands volts)

and a reduced current with section of cables which is a

compromise between low resistance and weight of the

cables.

- Since intensity of current and voltage are directly

proportional, their ratio, being constant, gives the

value of the conductor's resistance.

If we need to calculate this parametres and we do not

remember the formulas, we can try and use the following

diagram:

Ohm's law

Move your mouse over the pictures to

see how it works.

Just hide with your finger the

parametre you have to get (you'll have to know the value

of the others, of course...), e.g. the voltage:

If we need the current:

If we have an interest in the

resistance:

Till now we have seen the electric current while flowing through a conductor, without taking into account neither its effects nor its possible use; the effects are essentially as follows:

Thermal effect: we already mentioned it while speaking about the resistance; it is generated by the electric attrition of the material and consists in the development of heat inside the conductor; it is also named "Joule effect".

Magnetic effect: when a current flows through a conductor generates a magnetic field equivalent to the field generated by a magnet.

Chemical effect: it is generated when the current flows through a chemical solution; the molecules are dissociated and the atoms that compose them become ionized, stitching themselves to the electrodes of opposite sign; the phenomenon is exploited particularly in the electroplating workshops; it is also exploited in batteries and accumulators, pieces of equipment we will study soon.

Physiological effect: it interests especially the prevention of labour accidents; the electric current, especially with high voltage and intensity, is dangerous and produces rouinous effects in the human body. With differences that vary from person to person, the tolerable current is about 15 milliampères (0.015A); taking into account that, in certain conditions, the resistance from hand to hand may be as low as 10.000 ohms, the deadly voltage can be, applying the Ohm's law (V=RI): 10.000 * 0.015 = 150V, a voltage quite common to be found in everyday life. On the other hand, a simple linear amplifier tube set, very common in any Amateur's lab, can reach voltages well over 2000 V! Obviously the fatality of the discharge depends on the crossed zone: from hand to hand the current passes through the heart causing its fibrillation. If the body is bathed or the hands are wet, the resistance decreases, making the domestic voltages very dangerous. Besides the electric current flows through the liquids, also when they are flowing and regardless of the direction. In the past a child tragically died urinating for fun from a railroad 's viaduct on the underlying cables. The moment the liquid hit the cables, the current flew up to the child, killing him. In any case, even if it is not always deadly, the electric current always causes painful shakes or deep burns and needs therefore to be treated with respect……

To produce all these effects (physiological apart!) we need to let the electric current flow through particular components, conceived to exalt and exploit a particular effect; such components are connected through wires (also named cables when they are very large) to a generator.

Among these components we will now examine:

The resistor: it is composed of material of high resistivity (nichelcromium, costantana, graphite, mixes of coal, special leagues). The body is generally a ceramic cylinder, on which some metallic wires (for the wire-resistors) are wound or a resistive mix (for the mix-resistors) is deposited; two short pieces of wires, named rheophores, are connected to the tips of the cylinder. The resistor concentrates in itself the phenomenon already examined of the electric resistance; it exploits the thermal effect (or Joule effect).

The symbol of the resistor is the following:

The resistor behaves the same way in direct or alternating current and it always dissipates energy.

The inductor: it is normally composed of a electric wire wound to spool, with or without support according to the rigidity of the wire; it also has two tips named rheophores (in case it has more intermediary wires, they are named taking) and a number of coils. It exalts and exploits the magnetic effect, more intense if a ferrous nucleus is inserted inside the coils.

The symbol of the inductor is the following:

With intermediary taking

With nucleus

The inductor has a different behaviour in direct and in alternating current, we will examine such behaviour in details when we will study deeply the component; in direct current it doesn't oppose the flow if not for the resistive value of the wire composing the same inductor; an ideal inductor (non-existent because the material always introduces a resistance, however low) does not dissipate electric energy but returns it in form of magnetic energy.

- The capacitor: it is constituted by two leaned out plates; a rheophore is connected to the centre of every plate; the plates are separated by a space, which can be empty or filled by insulating material (as mica, glass, paper, politene, ceramics or other); this space is called dielectric. The wider the plates and the thinner the dielectric, the higher the capacity of the capacitor. The capacitor has got the property to accumulate electric charges, as the clouds do (we mentioned it at the beginning of our course); the higher the capacity the more electrical charges can be stored.

The symbol of the capacitor is the following:

As we have already seen for the inductor, the capacitor has a different behaviour in direct and alternating current; we can say that it behaves the opposite manner if compared to the inductor: in fact an ideal capacitor (non-existent because the resistance of the dielectric is never infinite) constitutes a total block to the passage of the direct current and it doesn't consume energy.

We will see now how these units behave, if inserted in a electric circuit, for the present powered by direct current, but beforehands we will examine some auxiliary units wich: 1) produce the current, 2) measure the current, 3) insert or exclude it:

- The generator: symbol=

This is a symbol of a generic generator and it doesn't specify the kind of generated current. Generators for only direct current are the cell and the accumulator (or batteries of accumulators); their symbol is the following:

A particular dc generator is the power supply . Rather than a generator it is a device which takes away from the network the alternating current, rectifies it (that is excludes the negative portion of the ac) and levels it at the peak value (we will see later), converting it to dc.

It is symbolized like a generic source of d.c. that is:

Or

Or

All generators have a proper resistance, called internal resistance (or impedance) and we need to take it into account, dimensioning the circuit. The lower the internal resistance, the more efficient the generator.

- The measurement instruments, generic symbol :

It can indicate a volmetre or an amperometre, according to the position in the circuit, if instead we need to be specific, it is necessary to use the instruments with their proper symbol, that is:

The Voltmetre, symbol:

It gauges the voltage in volt (V) or in its multiples (Kv: read kilovolt equal to 1000 volt), or sub-multiples (mV: read millivolt equal to 1/1000 volt or mV: read microvolt equal to 1/1000.000 volt).

The voltmetre is always placed in parallel to the measured circuit (We will see soon what it means).

The Amperometre: symbol:

It gauges the current in ampère (A), or in its submultiples (mA: read milliampère equal to 1/1000 ampère; mA: read microampère equal to 1/1000000 A) The picoampère equal to a billionth of A exists as well. Its measurement is possible only with ultra-sensitive instruments, not affordable by a common radio-amateur.

The amperometre can be always placed in series (we will see soon) to the measured circuit.

- The switch: symbol:

It's used to open or close a circuit. Without it it would be necessary to attach or detach the load manually, action obviously too umcomfortable; by the switch it's possible to have the load permanently inserted and to put or to cut off the current flow.

Let's mention also the load, which can be a electric motor: symbol:

It's used to open or close a circuit. Without it it would be necessary to attach or detach the load manually, action obviously too umcomfortable; by the switch it's possible to have the load permanently inserted and to put or to cut off the current flow.

Let's mention also the load, which can be a electric motor: symbol:

a lamp: symbol:

a loudspeaker:symbol:

a simple resistor or other.

All loads have a proper impedance and all consume energy; therefore can be indicated like a resistor of such impedance.

When a load is a pure resistor (or a lamp which is a simple resistor) all the consumed energy turns in heat.

Other symbols will be introduced as soon as we will use the correspondent devices.

And now the most simple of all circuits:

We can see that it's composed by a dc generator, by a resistor (but can be also a motor, a lamp or a transmitter with the same impedance), by the wires which lead the current and by a switch. In series to the circuit, i.e the current passes trough it, stays a amperometre, while in parallel to the circuit, that is in a position which embraces both poles (+ and -) stays a voltmetre. In this case, for convenience, we have posed it at the ends of the resistor, but it can be at the ends of the generator or after the switch and the amperometre: the measure would not change.

When the swithch is closed, the current flows in the arrow sense (conventional sense), crosses the resistor and the amperometre, coming back to the generator, and so on in a continuous cycle. The needles of our instruments indicate something.

Supposing our generator free of internal resistance and giving a constant voltage of 1V, our resistor having a impedance of 1W, we will see that the amperometre will indicate 1A , while obviously the volmetre will indicate 1V. Actually, applying the Ohm's law: I = V/R , i.e. I = 1V/1W= 1A .

Touching the resistor, we will notice that it warms up, sometimes close to burn. As a matter of fact the electrons, overcoming the electrical attrition, must accomplish a work, which regularly turns in heat! The heat unit is the calorieand the work unit in the system Meter,Kilogramme,Second (MKS) is the Joule, equal to .24 calories (whence the joule effect) .The work accomplished during a time unit corresponds to a Power (symbol P). The power unit is the Watt; 1 joule per second corresponds to 1 Watt (symbol W). However also 1 V*1 A corresponds to 1 W; as we can enunciate with the following formula:

P = VI but, according to Ohm's law: V=RI, i.e.

P=(RI)I, that is again: P = RI2 .

In addition, again according to Ohm's law: I=V/R, therefore P=V(V/R), i.e.

P = V2/R.

We have therefore three expressions for the power:

P = VI ; P = RI2 ; P = V2/R .

From each expression we can extract every single element, knowing the others. Here also we can rely on the mnemonic trick already employed with the Ohm's law, keeping in mind that a scheme for each expression is required; i.e.:

We will examine the first only:

If we need P:

If we need V:

If we need I:

Analogously for the other scheme, keeping in mind that the elements as I and V must be elevated to the power of two beforehands and, in case of the result we need to extract the square root beforehands

|

Oppure

Oppure