Mutt and Jeff met at the usual time for their adventures at the Swap Shop on this cool morning in mid-March 2004.

Not much in the way of numismatics today. Mutt did find a book on history, which he noted in looking at the index, had a few pages listed under currency.

Today with our new colorful TWENTIES and the price of gold above $400. we forget that the history of paper money is much older than 1933, when the U.S. Government demonetized gold.

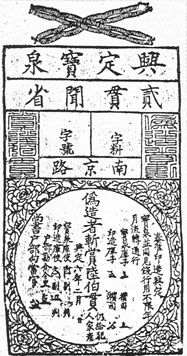

Mutt and Jeff found the following story very interesting, with thanks to the Author and the copy of a Chinese note from Marco Polo's time in an all Chinese Coin Book.

When Marco Polo visited the China of Kublai Khan (1216 - 1295), he saw nothing worth reporting in their multiplying of sacred texts by block printing. But he did note with astonishment how Kublai Khan by a kind of alchemy had made printed paper, in place of precious metals, serve as currency.

Of this money the Khan has such a quantity made that with it he could buy all the treasure in the world. With this currency he orders all payments to be made throughout every province and kingdom and region of his empire. And no one dares refuse it on pain of losing his life. And I assure you that all the peoples and populations who are subject to his rule are perfectly willing to accept these papers in payment, since wherever they go they pay in the same currency, whether for goods or for pearls or precious stones or gold or silver. With these pieces of paper they can buy anything and pay for anything. And I can tell you that the papers that reckon as ten bezants do not weight as one. .

Here is another fact well worth relating. When these papers have been so long in circulation that they are growing torn and frayed, they are brought to the mint and changed for new and fresh ones at a discount of 3 per cent. And here again is an admirable practice that well deserves mention in our book: if a man wants to buy gold or silver to make his service of plate or his belts or other finery, he goes to the Khan's mint with some of these papers and gives them in payment for the gold and silver which he buys from the mint-master. And all the Khan's armies are paid with this sort of money.

After having for years tried to support and maintain these notes, the people had no longer any confidence in them, and were positively afraid of them, for the payment for government purchases was made in paper. The fund of the salt manufactories consisted of paper. The salaries of all the officials were paid in paper. The soldiers received their pay in paper.

Of the provinces and districts, already in arrear, there was not one that did not discharge its debts in paper. Copper money, which was seldom seen, was considered a treasure. The capital collected together in former days was. . . a thing not even spoken of any more. So it was natural that the price of commodities rose, while the value of the paper money fell more and more. This caused the people, already disheartened, to lose all energy. The soldiers were continually anxious lest they should not get enough to eat, and the inferior officials in all parts of the empire raised complaints that they had not even enough to procure the common necessities. All this was the result of the depreciation of the paper money.

Following the example of the more advanced people they had conquered, the Tartars began issuing their own paper currency, and after 1260, when Kublai Khan completed his conquest of China, he made it the regular institution reported by Marco Polo. In Marco Polo's day the notes were still passing at full face value, but in the last years of the Mongols' Yuan dynasty (1260 - 1368), floods of paper money once again signaled inflation. When the first emperor of the new Ming dynasty (1368—1644) took over, he cut back the paper money in circulation, and finally succeeded in stabilizing the currency.

Boorstin, D. The Discoverers Random House p. 502-3, 1983.

People's Bank of China. Currency through out history 1600BC to 2000AD plate note