VI. History

- Rivers & Lakes

- Climate

- Natural Resources

- Plants & Animals

- Population Characteristics

- Political Divisions

- Principal Cities

- Religion

- Language

- Education

- Culture

- Agriculture

- Mining

- Manufacturing

- Energy

- Currency & Banking

- Commerce & Trade

- Labour

- Transport

- Communications

- Executive & Legislature

- Political Parties

- Judiciary

- local Government

- Health & Welfare

- Defence

- International Organizations

VI. History

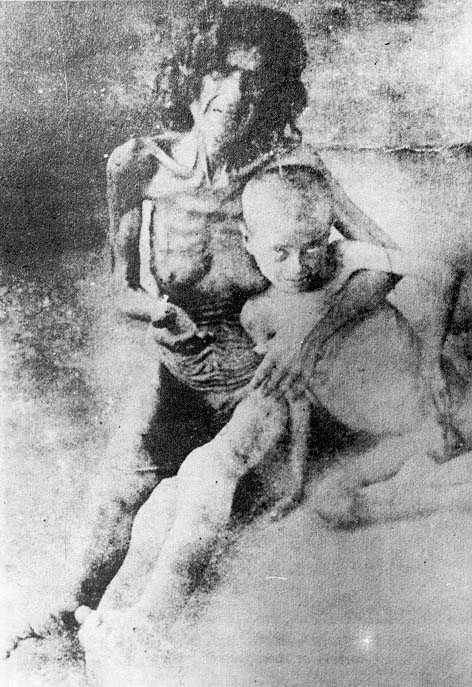

Armenia suffered from extremely harsh treatment by foreign powers several times during its history. The invasion of the Seljuk Turks in the 11th century resulted in the first large-scale emigration of Armenians. Other periods of emigration followed, especially during the late 19th century, when Armenians were persecuted by Turkish and Russian governments for agitating for political reforms. Armenians were massacred on a large scale by Turkish forces. The Russian government, although not as repressive as the Turkish government, closed Armenian schools and ordered the confiscation of Church property. Even larger massacres occurred during the 20th century as the Turkish government of the Young Turk era (1908-1918) sought to move Armenians to Mesopotamia. Between 1915 and 1923 more than 1 million people were estimated to have died from the Turkish action.

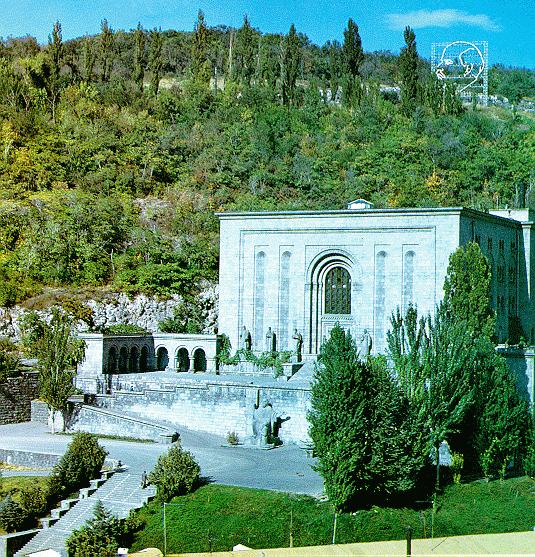

In 1918, Armenia declared itself an independent state after the short-lived Transcaucasian Federation with Georgia and Azerbaijan collapsed. In 1922 Armenia was incorporated into the USSR as part of the Transcaucasian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic. In 1936 Armenia became a separate Soviet Socialist Republic within the USSR.

In the late 1980s popular unrest demonstrated the desire for Armenian independence, despite half a century of Soviet rule. Under Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev, Armenians took advantage of the policy of glasnost (Russian for “openness”) to publicly decry the state of the environment and rally for the annexation of Nagorno-Karabakh, an Armenian enclave in Azerbaijan. In 1989 the Armenian Supreme Soviet declared the enclave part of Armenia and proclaimed the sovereignty of the republic of Armenia. In September 1991 Armenian residents voted overwhelmingly to secede from the USSR, and the Supreme Soviet declared Armenia a sovereign, independent state in the same month. In October 1991 Levon Ter-Petrosyan, formerly chairman of the Armenian Supreme Soviet, became the first popularly elected president of the new republic. Armenia became a member of the UN in 1992.

Political tension in the country increased sharply in the first years after Armenian independence. Difficulties presented by the aftermath of the 1988 earthquake, the war with Azerbaijan over the disputed region of Nagorno-Karabakh, and the economic blockade of Armenia by Azerbaijan resulted in an increase in political opposition to the government. The ruling party, the Armenian Nationalist Movement, which promotes a moderate programme of economic reform and territorial delimitation, was challenged by a wide array of political parties. The foremost was the Dashnak Revolutionary Federation, which has been in existence for more than a century and was the ruling party during Armenia’s brief period of independence from 1918 to 1922. The Dashnak, which exerts a great degree of control over Armenian military forces in Nagorno-Karabakh, rejects economic market reforms and advocates closer ties with Russia. Because of political pressure from Dashnak and other opposition groups, Kosrov Arutyunyan was forced to resign as prime minister, and an interim prime minister, Grant Bagratyan, was appointed in 1993. In 1993 Armenian forces defeated the Azerbaijani army in several confrontations, which led to Armenian control of Nagorno-Karabakh and adjacent areas.

Some of the advances made by the Armenians were reversed in December 1993, when Azeri forces launched a counter-offensive, and a ceasefire was negotiated in May 1994. Continuing economic problems resulted in the announcement of an austerity programme in November 1994. A worsening internal security situation led the government to implement measures to combat terrorism, including the suspension of the leading opposition party (ARF), which was charged with assassination, terrorism, and involvement in drug trafficking. Two rounds of the first post-Soviet legislative elections and a referendum on a new constitution took place in July 1995. The nationalist group took 119 of the 190 seats (the 131-seat National Assembly followed when the new constitution came into force). In February 1996 the IMF approved a US$148 million three-year loan to support economic reforms during 1996-1998. The incumbent president, Levon Ter-Petrosyan, was returned for a second five-year term, with over 50 per cent of the vote, in September 1996, and the result attracted charges of vote-rigging from opposition parties and led to demonstrations in Yerevan. In October the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) reported on its observation of the elections, and noted that it had reason to “cast doubt on [their] validity”. In November, Bagratyan resigned and was replaced by Armen Sarkissian; a major Cabinet reshuffle followed.

In March 1997 Sarkissian resigned on health grounds and his successor Robert Kocharyan was appointed by President Ter-Petrosyan two weeks later. Kocharyan was president of Nagorno-Karabakh and his appointment was seen as a move to ease tensions in Armenia. A proposal in June to initiate conscription, prompted the Speaker of the National Assembly, Babken Ararktysan, to tender his resignation. He resumed his post after President Ter-Petrosyan announced that further discussion on conscription would be postponed, and, if approved, the law would not become effective until 1998. During a visit to Russia in August, Ter-Petrosyan signed a treaty of friendship and reached agreement on the export of natural gas from Russia to Turkey via a pipeline through Armenia. Ter-Petrosyan suggested in the autumn that Armenia be more flexible in its approach to the question of Nagorno-Karabakh, by adopting the plan put forward by the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE). Ter-Petrosyan was forced to resign in February 1998 by dissenters, among them Prime Minister Kocharyan, who were unhappy with his policy plan. In the presidential run-off election in late March, Kocharyan was elected with almost 60 per cent of the vote, and Armen Darbinian, who was previously the finance minister, was appointed Prime Minister in early April.

Following ratification of legislation to legalize the Dashnak party (the Armenian Revolutionary Party), President Kocharyan appointed two members of the ARF to his administration in May. In the same month Kocharyan announced the establishment of a commission on the constitution that was expected to recommend a reduction in the powers of the president; the constitutional amendments would be subject to a referendum. In July it was announced that the Supreme Court was to be disbanded and replaced by a Court of Appeals that would be divided into civil-economic and criminal-military divisions; this restructuring was part of a number of reforms to the legal system that were expected to become effective during 1999.

Fighting in Nagorno-Kharabakh

Armenian Genocide

20th Century First Genocide