"If Wally Knew"

"If Wally Knew"

By Katy J. Vopal

Written for "Non Fiction Workshop" at the University of New Orleans, September, 1999.

When I was fourteen, Wally caught me with a full bottle of Vodka in my hands just as I quietly eased it out my father's liquor cabinet. My best friend, Tracy, was having a slumber party because her parents were out of town. With no parents scheduled to be around, I eagerly accepted her invitation. My own parents were out for the evening, leaving my grandfather in charge of my brother, Matthew, and me.

The liquor cabinet is located in the hallway between the living room and kitchen of my parents' house. It used to be a closet, but someone renovated it so it was equipped with a nice countertop and two cabinets beneath. With both parents home, it was almost impossible to reach in and grab a bottle out of their impressive liquor collection: only tapped into at holidays and dinner parties after we kids had gone to bed. As I hit puberty, the fascination of doing all I was told not to grew. Being drunk was exceptionally appealing to my group of friends. My friends and I planned endlessly: what liquor to drink and when. It didn't matter that we looked like lovely, innocent examples of our all girls' Catholic school: we were kids, and the polyester plaid uniforms and crisp white blouses didn't make us angels by any means. The plot fell into motion when the slumber party was planned, and I was nominated to bring the liquor, not only because I had easy access, but because producing a full bottle of Vodka to a group of teenagers makes one a hero. I wanted that status.

That evening, Wally was dozing lightly on a chair in the living room. An empty glass that once held a Manhattan was on the table beside him. The Manhattan was Wally's drink of choice. Everyone else was drinking, why couldn't I? Finding it unfair I would have to legally wait seven years to sample such adult pleasures, I dropped to my knees quietly in front of the cabinet and pulled open the doors just out of Wally's range of vision. There was so much to choose from: Crown Royal, Gin, an array of wines, and the coveted Vodka. "Vodka," Tracy reasoned, "can be mixed with anything. Plus it gets you drunk quicker." It wasn't that Tracy was a liquor connoisseur, we were just going by what we had heard other people say.

The Abslout was in the back behind several rows of bottles. I grabbed the top, surprised at how heavy it was. The bottom of the Absolut hit a squat bottle of Amaretto with a small clink, and I froze. After a few moments, I relaxed. I pulled it all the way out of the liquor cabinet and closed the doors. The breath I hadn't realized I was holding released. Victory!

"What do you think you're doing?"

Wally.

My grandfather was a large man. He stood at an even six foot six inches tall, slightly overweight, with long arms and legs and hands the size of frying pans. From where I was kneeling on the ground, Wally seemed to go on forever. My heart stopped as I clutched the bottle to my chest.

"Nothing."

"Are you stealing liquor?"

He reached down and took the bottle from me in a flash. He read the label and his eyes pierced me. Wally's bright blue eyes were always kind, but now they darkened with disappointment. That scared me. So did the silence. A terrible, achy feeling of guilt swept through me.

"So, you want to try a drink? We'll drink."

Wally took me by the arm and pulled me to my feet. With granddaughter and Absolut in tow, he led me to the dining room where a large buffet held my mother's fine dinnerware and company glasses. Wally set the bottle down and opened one of the cabinets in the buffet. He carefully pulled out two small glasses. I watched Wally open the Vodka. He poured a shot in each.

Wally picked up one glass and slid the other over to me. "Let's have a drink."

I took my glass with trembling hands. The stench from the Vodka burned my nostrils. I looked up at Wally helplessly, and he smiled back at me with faint amusement. "Go on. You wanted to drink. Here's your chance."

"But, Grandpa..." I started to say.

Wally motioned at me with his own glass. I took a deep breath and swallowed some of the Vodka. My eyes filled with tears and my throat burned. I thought I was going to die because I couldn't breathe. Somehow, I managed to swallow and the sensation of pure Absolut hit me and I almost fell backwards. For a fourteen year old who had only sampled wine at an anniversary party years before, the straight shot was awful. Wally took my glass from me and pounded me on the back as I started to cough. I ran out of the room and into the kitchen, where I gulped cup after cup of cold water. When I was done, I was crying. Wally came up behind me and patted my shoulder, and told me to go upstairs to my room. When Tracy came by to pick me up for the slumber party, Wally simply told her I wasn't feeling well. I vaguely remember my parents coming home, and I waited for them to come upstairs and scream at me, but they didn't. Wally never told, and neither did I.

Thanks to Wally, I didn't touch liquor again until I was in college. The first time someone pulled out a bottle of Absolut, I politely refused. Wally was one of those people who left an impression, and I know I had no ordinary grandfather. Many people were intimidated by the sheer size of him. Wally wore cotton pants, and threadbare shirts which he took off in the summer, leaving him to lounge in his white undershirts. He liked sitting on old white metal patio chairs and work on "Find-A-Word" puzzles for hours. He was too sweaty, and too scruffy. I used to hate when he would pluck up the grandchildren, one by one, and give us sloppy kisses and pinch our cheeks. His monstrous hands always looked like they could crush us in an instant, but he was always gentle with children. He bought us frozen custard, handed out quarters. And whenever I had a recital, a basketball game, or landed a part in the school play, Wally was always there, sitting in the crowd and towering above anyone else.

I had a hard time in high school. Unfortunately, I inherited Wally's shape: too tall and too big. When you're a girl, a teenager, and wanting desperately to fit in with everyone else, be like everyone else, and have a date like everyone else, it isn't easy. I went to the mall with my friends and never enjoyed it the way they did. I had to worry about finding pants that would fit me first of all, and then I had to worry about if they would be long enough. They didn't make the latest fashions in plus sizes, and it hurt. I wanted so much to be little, even if just for a day, and be cute and admired. Instead, I suffered with plain clothes and the taunts of "Jolly Green Giant" whenever some cruel people made me their target. It didn't take me long to realize society isn't kind to large people.

I wasn't just different size wise, though that was plenty. I was creative, spending long days dreaming up stories and plays when my friends had dates and went to dances. I learned early on in my high school career that dances only meant more suffering, because no boy wanted to dance with someone who was taller than they were. I didn't have any interest in boys anyway, but longed to be asked to dance just once so I had some boasting rights among my friends at lunch time.

Most people asked me how I was doing in school (terrible), what I did on weekends (nothing), and if I had a boyfriend (not on their life). But it was Wally that asked, "Write anything new lately?"

To him I could say, yes.

Wally was a master storyteller. He always had an audience, because he knew half the people in Milwaukee county. The running joke among out relatives was that Wally couldn't go anywhere without knowing somebody. He spun tales of people and places he had seen and been, and everyone listened with great earnest.

"That's some story, Wally!" people would hoot. Then Wally would pound me on the back, his voice and laugh growing heartier with each Manhattan, and say, "My granddaughter here tells some good stories. Tell them what you write!" I would turn red and mumble enough to please Wally and his court, and wish Wally would stop boasting.

One of the best things about Wally was that he had the rare gift of not caring what people thought of him. It was another of his lessons that was a lot harder to instill in me than staying away from liquor. Wally was scheduled to pick me up from school one day. It had been a pretty good day, until some boys waiting for their girlfriends outside the school building spotted me. They snickered as I walked past, but I tried to hold my head high. I knew they were laughing at me. "What an amazon," one whispered. I sat on the stairs that led up to the gym, several feet away from them. School busses and cars drove past me in a line, and I kept hoping I would see Wally's car. The boys said something I couldn't hear, and laughed again.

Hurry, hurry, I silently prayed. Finally, the lumbering brown car came around the corner of the school. I jumped up and the boys laughed even louder. One of them called out "Someone needs some Slim Fast!" Another said, "She sure is big!"

I flew into Wally's car and slid down in the seat as far as I could go. I was on brink of tears. Wally looked across the driveway and I'm sure he saw the laughing boys. He waited until we were a safe distance from the school before he asked, "What's wrong?"

"Nothing."

"Sure. Nothing's wrong. You're crying. Tell me what happened."

On the long, bumpy ride home I cried to Wally about how I was tired of being teased, and why couldn't I look like everyone else? I twisted my plaid uniform skirt in knots. I was not only big, but tall, too. I hated the endless height jokes, did I play basketball, and how was the weather up there. Miserable.

"If someone asks me how the weather is up here, I say ‘Why? Are you standing in a hole?'" Wally said.

I stared up at him, admonished. Wally got teased? Everyone liked Wally. It seemed impossible. "Who teases you?" I demanded.

"A lot of people," Wally replied. "Not as much as they used to.. You're a big person. You either use it to your advantage, or you let it make you miserable. Don't let other people's ignorance and stupidity get the better of you."

It's those moments with him that are the most vivid. There are so many inside that I hold close. Wally helped guide me through childhood and through high school, and at my graduation party he toasted me with every Manhattan until he fell asleep in the recliner, snoring.

The summer after graduation, I was busy helping my parents and other relatives plan a surprise 50th anniversary party for Wally and my grandma. I was leaving in August for college to study creative writing, but the date of the party was two weeks before. In between work and packing, I assisted in picking out invitations, flowers, and the catering menu.

One hot July day, Wally had chest pains. He tried to dismiss it, but my grandmother insisted on calling a doctor. She tried calling our house first, asking for my father, but I told a small fib because my parents were out buying flowers for the surprise party.

Since she didn't get anywhere with me, Grandma called 911 because Wally got worse. When the paramedics arrived, Wally walked to the ambulance, insisting he was fine. He probably made a few jokes with the paramedics. He walked into the hospital. There he had a heart attack and fell over. He never got up.

Flowers ordered for a party were then used for a funeral.

No one thought Wally would go when he did. He was the one who was so full of life. Wally knew everybody. Good old Wally, the life of the party -- we all thought he would live forever. He was the first one of my grandparents to die, and it was one of the hardest things I had to face. How I could imagine not waking up and finding out Wally had dropped by to have a morning cup of coffee with my dad? What would Christmas and Thanksgiving be like without him? How could Wally not be around to see me graduate from college? He'd been so proud I made it in. All these thoughts boiled inside me, complicated by the fact I had to dress up in a skirt and nylons, sit in a hot church, and see Wally in a casket looking like he was going to sit up any minute, look around, and say, "Hey, George! Hey, Jerry! I haven't seen you guys in a long time. How the hell ya doing?"

I didn't cry because I was too busy being mad at everyone and everything. So many people came in. Hundreds. I didn't know Wally knew so many people. Whenever Wally saw a large funeral procession, he would say, "Somebody important must have died." Now someone would see all the cars parked outside and that someone might make the same comment.

I had been asked to "write something nice" for Wally's funeral. I cringed at the sea of faces who were whispering how sweet it was that one of Wally's grandchildren was doing a reading, even if was that "odd one" Katy J.

After the service, they closed the casket, and then it was time for the eulogy. Catholic funerals take forever and I just wanted to get out of the church with all the sobbing and whispering. My Uncle Tom, who isn't really an uncle but has known our family long enough to hold the title, gave the eulogy. I didn't hear a word he said, until he pulled a small glass out of his suit coat. It was a glass similar that Wally had filled with Vodka that fateful day, and also similar to the glasses Wally himself had sipped many a drink out of. Uncle Tom put the glass on top of the casket and said, "Well, I guess Wally is having a Manhattan with the good Lord right about now."

Then, and only then, did I cry.

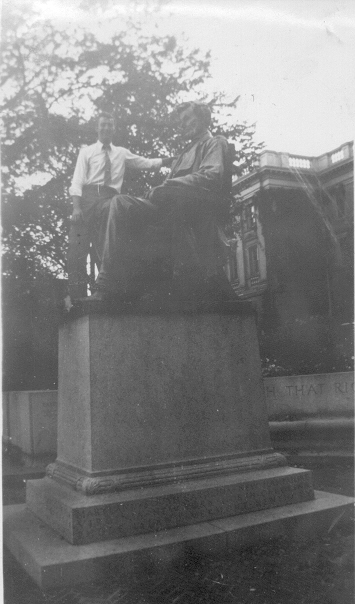

Several years later, I took a trip to Vincennes, Indiana with a few friends. It's a small town about 45 miles south of Terre Haute, where I went to college. There isn't much in Vincennes, except a pretty riverfront park with a huge statue of Sir Frances Vigo, the French explorer who helped found that part of Indiana known as The Wabash Valley. The scowling statue sits on the bank of the Wabash river, his back to the water. I was unable to resist climbing up on the statue, striking a pose, and putting my arm around Mr. Vigo like he was an old friend. My friends thought this was hilarious, and took a picture.

That Christmas, I was rummaging through a box in my dad's garage, when I found a stack of old pictures. There was grandma in her younger days, and my dad as a child. Then I found the picture of Wally, in Madison, Wisconsin, standing up on a large statue of some nameless politician, arm around the statue and grinning broadly for the camera. I took it back to Indiana with me, and pulled out the picture of me on the Frances Vigo statue. Side by side, the pictures show two different generations, some fifty years apart, doing the same thing. It's an enigma to me.

When someone touches your life, there isn't any writing or explaining that can do them justice. That's how I feel about Wally. I often wish he could have lived to see the person I've become. Thanks to him, I suppose I've turned out all right.

The few times I drank Vodka it made me sick. I learned to love myself, weight and all, height and all. I love telling stories and no longer mumble when people ask me what I write. I haven't crawled up on any more statues, however. I moved to New Orleans to pursue more school, and a career in writing and publishing. A few days after I moved, I was putting gas in my car and a greasy man passed by and said, "Hey, how's the weather up there?"

"Why, are you standing a hole?" I replied.

The man moved on. Take that, I thought, you ignorant sonofabitch.

If Wally knew, he'd be proud

Legacies Are Forever

Wally Vopal, 1945 on the Lincoln Statue in Madison, WI on the right

Katy J. Vopal, 1998, on the Frances Vigo Memorial Staue in Vincennes, IN.

Katy J. Vopal, 1998, on the Frances Vigo Memorial Staue in Vincennes, IN.

Any questions or comments? E-mail me!

Return to Search For a Legacy or Vopal Surname.

"If Wally Knew" c1999 by Katy J. Vopal. Please do not take this story without permission. Thank you.