Reply To Vanity Fair and F.O.B.

by C. Clark Kissinger

"...a myth that, if repeated enough, could begin to carry the authority of absolute truth." -- Buzz Bissinger

The Real Myth in the Case of Mumia Abu-Jamal

In 1995, an international movement against the execution of author Mumia Abu-Jamal came into existence. Taken aback, the political establishment in Philadelphia hit upon the idea of using the widow of slain police officer Daniel Faulkner as the symbol for a national campaign to demand Jamal's execution. Ever since, there has been a concerted attempt to hide the real issues in the case of Jamal, and to project instead the "human interest story" of a lonely widow, fighting valiantly by herself for justice and for closure -- her everyday existence tortured by rich Hollywood liberals, radical political activists, and Jamal's evil lawyer who feeds them false information. The August issue of Vanity Fair magazine, a Condé Nast publication aimed at the up and coming, contains yet another rehash of this official myth.

Those voices asking for an impartial examination of what has been a travesty of justice in Jamal's case are waging a very uphill battle against the most powerful forces in the land.

On the national level, both the Congress and the Supreme Court have been seeking a return to the era of "states rights," sharply restricting any federal review of state court justice. Major political figures have made it quite clear that they are prepared to see innocent people executed rather than have the death penalty itself called into question. In the world community, only the United States, China, Saudi Arabia and Iran still carry out executions on a large scale.

The case of Mumia Abu-Jamal has come to crystallize these larger issues for both sides, and that is why there are such powerful political forces behind the demand for his execution. As Evergreen State College president Jane Jervis put it so well, Jamal has used his voice "to galvanize an international conversation about the death penalty, the disproportionate number of Blacks on death row, the relationship between poverty and the criminal justice system."

We are also talking about Philadelphia -- a city synonymous with police corruption and a racist judiciary. This is the city that the Kefauver Committee came to for hearings on ties between the police and the mob. This is the city of Frank Rizzo, the infamous racist police chief and mayor, who took pleasure in attacking Black school children and personally arresting Black leaders like Malcolm X. This is the city where the leaders of the Fraternal Order of Police (F.O.P.) were themselves convicted in federal court of racketeering. Philadelphia is the only big city where the federal Justice Department brought suit to end police brutality. In the last few years, scores of persons have been released from prison after it was revealed that they were framed up by the police. And Philadelphia was recently chosen for a case study on racial prejudice in the application of the death penalty.

In fact, the real accomplishment of author Buzz Bissinger is that he is able to fill eight pages of Vanity Fair, without ever mentioning the names of any key players in the anti-Jamal campaign such as Ed Rendell, Rick Costello, and Mike Smerconish.

The idea that those campaigning for Jamal's execution are somehow the underdogs in the political arena borders on ridiculous. After all, it is Maureen Faulkner who went to Washington to sit on stage with President Bill Clinton and Attorney-General Janet Reno, not Pam Africa of MOVE. It is Jamal who is repeatedly attacked by ABC's Sam Donaldson on 20/20, not the Fraternal Order of Police. It is Jamal, not Maureen Faulkner, who has been denounced on the floor of the Senate by then minority leader Bob Dole and in the House by the current majority whip Tom DeLay. And it is the forces pushing for Jamal's execution that benefit from the feeding frenzy of both mainstream parties for more and speedier executions, with fewer questions asked.

The Attack on Jamal as a Journalist

One sure indication that Bissinger and Vanity Fair are out to low ball it, is their attack on Jamal as a journalist. In fact, Bissinger claims that Jamal never really reported on police issues at all! But his work in reporting on police brutality began with his work in the Black Panther party, first in Philadelphia and then on the national staff of the Black Panther newspaper.

Rosemari Mealy, one of the founders of the Black Panther Party in Philadelphia, recalls Jamal's work: "In 1969 there was a major incident which intensified the work of the Party, and that was the killing of a mentally retarded Black youth by a notorious cop named Bushwinger on 15th and Oxford Street. The young Lieutenant of Information [Jamal] spoke to the murdered youth's family and began to write in such a prolific manner of this and other wrongdoings of the Philadelphia police (having himself been a victim of their brutality)."

Since Bissinger can't think of a single instance of Jamal taking up the issue, let me refresh his memory about one highly publicized incident. After the first police attack on the MOVE house in 1978, where Delbert Africa was beaten and kicked by police on live TV, Mayor Rizzo held an angry press conference to defend the police action. In response to a question from a reporter, Rizzo lashed out: "They believe what you write, and what you say, and it's got to stop. And one day, and I hope it's in my career, that you're going to have to be held responsible and accountable for what you do." The reporter who questioned the police actions was Mumia Abu-Jamal.

Before he was railroaded onto death row, Jamal engaged in both print and radio journalism, and shared in an Armstrong Award for excellence in radio journalism. Since his imprisonment he has produced two books, written over 420 columns, and produced numerous audio recordings. Bissinger conspicuously avoids mention of "the Mumia rule" adopted by the Pennsylvania prison system that now bars all audio and video recording of prisoners by reporters. As Mumia has so eloquently put it, "they don't just want my death, they want my silence."

The Great Confession Hoax

Perhaps the most ridiculous claim in the whole frame up of Jamal is that he loudly confessed to shooting Officer Faulkner in the hospital emergency room. It's just so typical of the Philly cops, that when they don't have a case, they make one up.

You would think that if a group of trained police officers heard a suspect make a public confession, especially in a case where a police officer had been killed, they would report it. But no such report was made. In fact, the officer in charge of Jamal at the hospital wrote in his report that Jamal made no statement, and this is confirmed by the attending physician.

Two months after the night when Jamal was shot and then beaten by police, he filed police brutality charges against them. This made the cops go ballistic. At a meeting then held between cops and prosecutors, in which an assistant D.A. suggestively asked if anyone had heard a confession, several of them suddenly "remembered" that Jamal had confessed. Why hadn't they reported it at the time? Well, they were just too upset.

When this story was met with the skepticism it deserves, a hospital guard named Priscilla Durham (who was a friend of the deceased officer) was the next to suddenly "remember" that she too had heard the confession. In a lame attempt to add some credence to the story, she claimed that she had reported it the very next day to her supervisor. Of course, he didn't remember to tell anybody about it either, nor was he called into court to corroborate her sudden recall. So what it boils down to is that NOBODY "remembered" the confession for over two months, while the only written record from that evening states clearly that Jamal made no statement.

You don't have to be a legal scholar to see this is a pretty weak link in the case against Jamal. So Buzz Bissinger now jumps into the breach with a brand new confession tale. Only this time the memory lapse is years, not months. Perhaps we should hold a contest to see who can recall hearing Jamal confess after the longest lapse of time!

Some years ago, Philip Bloch was a volunteer with a prison aid society, and in this capacity he met Jamal. Jamal remembers him, and remembers that several years after he last saw Bloch, Bloch wrote him saying that he had become convinced that Jamal was guilty. Apparently Bloch's convictions have now blossomed into retroactive accusations. About Bloch's belated charge, Jamal says: "A lie is a lie, whether made today or ten years later. But I suppose Mr. Bloch wanted his fifteen minutes of fame in which case I hope he has received it. I find it remarkable that this rumor turned lie was never brought to my attention by the author, by Mr. Bloch himself or by Vanity Fair magazine which never contacted me. Welcome to snuff journalism."

Jamal went on to say, "If ever one needed proof of the state's desperation here it is. I thank Vanity Fair, not for their work but for stoking this controversy, because controversy leads to questioning and one can only question this belated confession."

The Prosecution's Case Warmed Over

Journalism students are always told that they must never engage in "advocacy." But in the real world, all journalists are advocates. The only question is, for whom? In Bissinger's case it's quite clear. He marches through a presentation of the prosecution's case while carefully avoiding the most serious evidence to the contrary. For example, Bissinger assures us that four witnesses testified to Jamal's guilt. Of course, there were ten eye-witnesses who testified to all or part of the events that led to Mumia's fast track to death row. Bissinger simply picks out the four who most closely agree with the prosecution and ignores the rest. He also conveniently forgets the special favors given to witnesses who changed their testimony to suit the prosecution (for a complete rundown on the witnesses, see "The KGO-TV Report" by C. Clark Kissinger and Leonard Weinglass).

Bissinger dismisses the idea that the shooter could have been a third person at the scene, then fails to tell his readers that the prosecution withheld from the defense for thirteen years the fact that the driver's identification of a third man was found on the dead officer.

On the ballistic evidence, Bissinger doesn't seem at all upset over how a bullet first reported by the medical examiner as being in two fragments and of .44 caliber, got itself together and became one bullet of .38 caliber. But then many strange things have happened in police department evidence lockers. Bissinger is very pleased that the metamorphed bullet is "consistent" with Mumia's gun. Of course, it's also consistent with tens of thousands of other guns. If Bissinger really wants to play investigative reporter, he might try to explain how a copper bullet jacket was found at the scene when the police ballistics expert testified that the bullets in both Faulkner's gun and Jamal's gun did not have copper jackets.

So Bissinger gives us his own "consistent picture of what happened that night." Not surprisingly, it is identical to the police theory of what happened, except that it omits how Jamal got shot. The police theory is that Jamal runs across the street when he sees a cop beating his brother with a flashlight. Jamal shoots Faulkner in the back at close range, and as he's falling, Faulkner gets off one shot at Jamal. The gravely wounded Jamal then supposedly walks over and shoots Faulkner in the face.

The problem with this story is that it doesn't conform to the evidence or the testimony. Faulkner was not shot in the back at close range, because there are no powder burns on his clothing. Jamal was not shot by Faulkner as he fell, because the trajectory of the bullet in Jamal's body is downward, not upward. And one of the prosecution witnesses (Michael Mark Scanlan) testifies that someone runs across the street to where Faulkner and Mumia's bother are, that there is a shot, and then a second shot after which Faulkner goes down.

The scenario that best fits the facts is this: Jamal runs across the street to aid his brother. Faulkner hears running steps behind him, spins around and shoots. Jamal attempts to duck, and the bullet enters his chest headed downward in his body. A second person, quite possibly a person in the car with Jamal's brother, then fires from some feet behind hitting Faulkner in the back. Faulkner goes down. The shooter then shoots Faulkner in the face and flees. A number of witnesses see a man running from the scene.

What is most annoying about Bissinger's hit-piece is the way he cavalierly attacks the defense, when he actually knows the truth of the matter. For example, Bissinger writes: "There is a question of why witnesses who might conceivably have been helpful in advancing the defense theory that another person had shot Faulkner were never called." Bissinger knows full well why other witnesses were not called. In the case of Officer Wakshul, who wrote in his report that Jamal had made no statement at the hospital emergency room, the defense was told that Wakshul was on vacation and was not available to testify. Today we know that he was sitting at home and was available, but Judge Sabo would not allow even a day's recess to try to find him. In the case of other potentially helpful witnesses, either their very existence was hidden from the defense, or the prosecution refused to give the defense the addresses and phone numbers where they could be reached.

Bissinger also assures us that the massive predominance of Blacks on death row in Pennsylvania "has nothing directly to do with the facts of the case." Apparently for Bissinger, racial prejudice exists only in the ethereal realm of statistics, and never impinges on the lives of actual Black defendants. Or perhaps a "fact in the case" like the prosecution using eleven peremptory challenges to knock African-Americans off the jury is not an instance of racial prejudice for Bissinger. This is precisely the sort of racial jury selection that was later outlawed by the U.S. Supreme Court.

Finally, Bissinger assures us that the Pennsylvania Supreme Court has examined Jamal's claims and rejected them. Here Bissinger fails to tell his readers quite a bit. First, the judge who held the hearings on whether Jamal should be granted a new trial was Albert Sabo, the same judge who conducted the original trial in 1982. Sabo was past the mandatory retirement age for judges in Pennsylvania, but the chief justice of the Pennsylvania Supreme Court signed a special order that allowed him to stay on the bench and hear Jamal's new appeal. Sabo then quashed most of Jamal's subpoenas for suppressed evidence, and passed on to the Supreme Court his finding that there were no errors in the original trial. The Pennsylvania Supreme Court then rubber stamped Sabo's findings about his own conduct in the first trial. The justices of this court are elected in partisan political elections, and five of the seven justices were endorsed and supported for election by the Fraternal Order of Police. Further, one of these F.O.P.-endorsed justices is a former District Attorney from Philadelphia who signed all the papers opposing Jamal's original appeal.

Failure to Read the Transcript

Bissinger repeats the frequent contention of the F.O.P. and prosecution, that those who support a new trial for Jamal have not read "the complete trial transcript." Of course he fails to mention that the transcripts of the 1982 trial, and the hearings for a new trial in 1995, 1996, and 1997, come to 12,306 pages, to which one can add thousands more pages of briefs and motions by both sides. The plain fact is that virtually no one, on either side of the issue, has read all the transcripts, nor do they have to in order to understand that Jamal never got a fair trial.

Certainly Bissinger hasn't read the transcripts, otherwise he would not make gross factual errors like saying that the defense called the 1995 witness who claimed that two different people shot Officer Faulkner, and that one of them jumped in a car and sped away. That witness, William Harmon, was called by Judge Sabo over the strenuous objection of the defense, precisely because he was not credible. Also, Judge Sabo's first name is Albert, not "Alfred" as Bissinger writes.

Bissinger goes on to ridicule author Alice Walker for only having read "bits and pieces" of the transcript. Yet "bits and pieces" of the transcript is exactly what F.O.P. has on its "Justice for Daniel Faulkner" web site, and Bissinger doesn't seem upset about that at all.

The F.O.P. frequently makes the claim that only people outside of Philadelphia support Jamal's bid for a new trial, but there are actually many people in Philadelphia who support a new look at Jamal's conviction. Many of them have experienced "Philadelphia justice" first hand, and know what life is like in the "deep North." But people who speak up for Mumia in Philadelphia do so at great risk. In other parts of the country and internationally, many thousands more have taken the time to look into the facts of the case, causing them to join the call for justice for Jamal.

Most people who examine this case for the first time find the case against Jamal so weak, and the procedures of his trial so flawed, that justice demands a fresh look in an unbiased venue. As author E.L. Doctorow put it so well: "It's inconceivable to me that unless someone has some political stake they would not want some further examination of the whole thing."

Someone With a Political Stake

One person who clearly has a political stake in the outcome of Jamal's appeals is Buzz Bissinger. Judges and other government officials are supposed to reveal when they have an interest in a pending decision. Unfortunately, journalists are exempt from this rule.

So who is Buzz Bissinger? Bissinger was a long-time reporter for the Philadelphia Inquirer and something of a figure in Philadelphia politics. Bissinger picked up a Pulitzer Prize for a series on the Philly courts, but was best known for covering mayoral politics in Philly. Bissinger and the Inquirer were aligned with those forces opposed to any political comeback by former Mayor Frank Rizzo. The sixties were over, Nixon had fallen, and the openly racist, head-cracking style of Rizzo was no longer wanted by Philadelphia's elite. Politicians like Wilson Goode and Ed Rendell were now slated to take the reins.

But in 1987, an aging Frank Rizzo made a comeback attempt. Bissinger was assigned by the Inquirer to cover his campaign. The anti-Rizzo articles written by Bissinger were credited by most observers with tipping this close election to Wilson Goode. The service was not forgotten, and when Ed Rendell replaced Goode in the 1991 election, Bissinger was invited into the Mayor's office -- literally. Rendell gave Bissinger complete access to his office and operations for the four years of his first term in office. This was not an act of altruism on Rendell's part. The quid pro quo was that Bissinger would write a book on Rendell.

Bissinger's book, A Prayer for the City (Vintage: 1997), is a lyric hymn of praise for Ed Rendell. Bissinger credits Rendell with "saving Philadelphia" by crushing the public employee unions and slashing city services -- sort of a Giuliani before his time. The book is filled with vignettes of civic figures, who are all conveniently classified as good guys or bad guys. Should we be surprised that most of Bissinger's good guys are white and most of his bad guys are Black?

Although Rendell was part of the new generation that overthrew Frank Rizzo, it was something of a palace coup. Rendell was also a product of the Rizzo era, serving as District Attorney while Rizzo was Mayor. With Rendell now reaching the end of his second term and barred by law from running for mayor again, he is looking at higher office. Rendell's name has been touted for governor and for the Senate.

The eight-foot skeleton in Rendell's closet, as he now goes for higher office, is that Rendell was District Attorney in 1978 when the police first attacked MOVE (beating and kicking MOVE members on live TV); Rendell was District Attorney in 1982 when Jamal was railroaded onto death row; and Rendell was District Attorney in 1985 when police dropped a bomb on the MOVE house killing 11 people (including 5 children) and burning down a Black neighborhood.

If Jamal is now vindicated -- if he is shown to have been framed up and a victim along with the MOVE organization of a deliberate miscarriage of justice -- then someone is going to ask: "On whose watch did this occur?"

Thus we find in Vanity Fair a marriage of convenience. The larger political agenda of pushing ahead the death penalty, in this case against a well-known political dissident on very suspect grounds, is married to the political interests of one politician and his personal publicist, Buzz Bissinger.

At the same time, by running out the widow-fighting-by-herself myth, Bissinger seeks to hide the role of Rick Costello of the Fraternal Order of Police. Unfortunately for the official myth, Costello has a big mouth and is constantly bragging about the F.O.P. raising the money and organizing the campaign for Jamal's execution (operated through a Pennsylvania dummy corporation, "Justice for P/O Daniel Faulkner, Inc."). Nor does Bissinger tell his readers about the chief cheerleader role of Michael Smerconish. On April 23, Smerconish organized 800 people to come to a $100 a plate dinner at Philadelphia's elite Union League club to raise money to campaign for Jamal's execution. As Bissinger well knows, Smerconish was a loyal side-kick and aide-de-camp to Rizzo and has served as a lawyer for the F.O.P.

Vanity Fair was warned in advance about Bissinger's bias, but decided to proceed with his story.

Unanswered Questions

When you can't answer the tough questions, you try to shift the terms of debate. And this is what Bissinger has to do. He talks about the widow-fighting-by-herself-myth, he talks about newly remembered confessions, he talks about Mumia's attorney defending political prisoners in other countries besides the U.S. He talks about everything except how Blacks were deliberately knocked off Mumia's jury, how evidence was suppressed, how Mumia's political statements from ten years earlier were used as an argument to the jury for giving him the death penalty, and how there is an overwhelming pattern of police and prosecutorial misconduct in Philadelphia.

And with good reason. The facts are not a favorable ground for the F.O.P. and the state to fight on. This is why they resort to emotional appeals based on the widow. She has become a stage prop used by others in a campaign to perpetuate a great injustice, and to extend a national program of callous disregard for rights of those accused.

The Vanity Fair article ends with the standard demand that Jamal give the prosecutors a free preview of how he will testify in federal court when his petition for habeas corpus is heard this fall. Well, Buzz, if you want to know, come sit in the courtroom and listen. In the meantime, you will have to make do with what Jamal said at the close of his sham trial in 1982:

"I am innocent of these charges that I have been charged of and convicted of, and despite the connivance of Sabo, McGill and Jackson to deny me my so-called rights to represent myself, to assistance of my choice, to personally select a jury who's totally of my peers, to cross-examine witnesses, and to make both opening and closing arguments, I am still innocent of these charges.

"According to your so-called law, I do not have to prove my innocence. But, in fact, I did have to by disproving the Commonwealth's case. I am innocent despite what you 12 people think and the truth shall set me free.

"This jury is not composed of my peers, for those closest to my life experiences were intentionally and systematically excluded, peremptorily excused. Only those prosecution prone, some who began with a fixed opinion of guilt, some related to City police, mostly white, mostly male remain. May they one day be so fairly judged."

* * *

Readers are invited to share their thoughts with Vanity Fair at vfmail@vf.com.

[posted 7/13/99]

Contact Refuse & Resist!

305 Madison Ave., Suite 1166, New York, NY 10165

Phone: 212-713-5657

email: refuse@calyx.com or resist@walrus.com

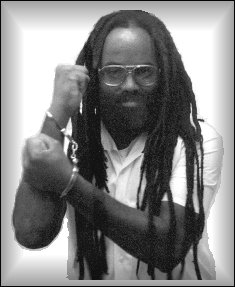

FREE MUMIA ABU-JAMAL

All photos on this page were reprinted with much gratitude and permission from the photographer Diane Greene Lent. More of her work can be seen at The Bretch Forum.