Artists like Witkin have sought to give meaning back to the monsters lurking under the bed of society. By placing them in situations unimaginable to the normal sensibilities, Witkin has brought them into a new reality that is all his own and in which he allows us to share. Through his unrestrained vision and technical mastery of the medium new messages and emotions; can come through. He opens the boundaries to acceptance and true beauty.

Artists like Witkin have sought to give meaning back to the monsters lurking under the bed of society. By placing them in situations unimaginable to the normal sensibilities, Witkin has brought them into a new reality that is all his own and in which he allows us to share. Through his unrestrained vision and technical mastery of the medium new messages and emotions; can come through. He opens the boundaries to acceptance and true beauty. The concept of beauty in modern society is almost permanently etched on the consciousness of the people. We have learnt to recognise and label things different to our own ideals as freaks or perversions. While we ostracise the part of society for being different, we glorify and equally small portion for the same reason. Our culture of idealised and almost naturally impossible beauty (ie supermodels) has in many ways, closed itself of to the darker and deeper emotions that exist at the other end of the spectrum.

Through this, the images that Witkin creates, just as unreal as those pop media present feed us, become more real. Unlike the pop media, Witkin’s interests in models include ‘pinheads, dwarfs, giants, hunchbacks, pre-op transsexuals, bearded women… people with tails, horns, wings…reversed hands or feet…anyone born without arms, legs, eyes, breast, genital, ears, nose, lips. All people with unusually large genitals…All manner of extreme visual perversion. Hermaphrodites and teratoids (alive and dead)…Anyone bearing the wounds of Christ.’(Celant) as well as cadavers and body parts of humans and animals.

Although these ‘freaks’ are a major part of the composition of the photograph, in the finished image they become part of a meaning that goes beyond a lone figure. Their faces are masked or hidden so that ‘the personality of the subject would not interfere with the potential image’ (Celant, 55) . Witkin often consults with his models about any ideas they may have about the shoot, any fantasies they may have, although the final creation is totally his. Witkin is a master in his craft and is well known as a perfectionist. He likely to produce around ten lovingly finished prints in a year and the results are always remarkable. His prints have an aged look that is the product of a painstaking printing process. The negative itself is scratched and, printed through tissue paper changing the texture of the print. It is mounted on aluminium and hand toned with pigments. Then molten bees wax is poured onto the print and reheated , emulsifying the surface, cooled and polished. The toning warms the blacks and whites while the scratches distances the subject matter further from our reality. All in all, this process succeeds in removing the image from any stream of time and like any raw emotion, becomes timeless without becoming static.

Witkin is well known for his borrowing from ‘high art’ and replacing it with his choice subject matter. His 1990 work, Feast of Fools looks like any other traditional still life (refer to Jan Davidz de Heem’s Still Life with Fruit and Lobster) and until the subject matter is examined. Besides the fruit lies a masked foetus, severed hands, legs and feet. Arranged like fruit the artist places them into an excepted form but its meaning becomes more. Every part of the image becomes symbolic, it is at once repulsive and arresting and somehow beautiful. Typically beautiful masterpieces such as Antonio Canova’s sculpture, Le Grazie becomes Witkin’s The Graces, New Mexico(1998). In this image, the three traditionally beautiful girls, the Graces, are replaced by three masked hermaphrodites in the type of figurative composition but totally different context. These are no longer innocents of light mythology but figures out of a darkened dreamscape. Yet, if you look beyond the ‘shame’ of being a hermaphrodite these figures are beautiful in their darkness.

In fact, the disregard of those sexually ambiguous beings in society is reversed in Witkin’s. In this alter reality, hermaphrodites represent the unity. The belief in god who both man and woman and neither is not truly practiced in our world’s culture. It is undeniable that the God of the three main monotheistic religions (despite the fact that he is a creator god) is seen as a man by his followers. Other god’s may have goddess counterparts, but the faith in a double sexed god is not evident. Therefore those who could represent this unity as the doubly blessed, as goodness, are also thrown into the heap of cultural freaks. In Gods of Heaven and Earth, his appropriation of a famous Botticelli work, Witkin works to overturn standing concepts of beauty (much of which was established by Botticelli) and to create a new beauty. In this version, the Goddess of beauty rising from the shell is a hermaphrodite as is the other ‘female’ standing to the right of her. Both figures would be considered beautiful women if not for their abnormality. Despite their beauty, the first reaction these beings is usually disgust. But it is also impossible to deny the beauty of their faces and forms. This dichotomy of ideas is a powerful tool throughout Witkin’s work.

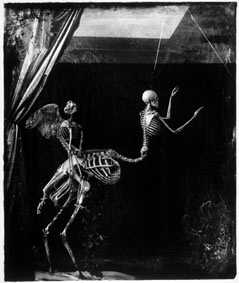

Much of Witkin’s own journey and exploration has been in a search for God. Born of a Jewish father and Roman Catholic mother (who divorced because of religious differences), Witkin is a practicing Roman Catholic. God, the ultimate force of creation, goodness and grace. For a long time he tried to find God in his art, his images, his redemption. "I chose to incarnate Christ as G-d, because I believe he is G-d and because he still represents the living belief of this culture. He is the symbol, regardless of historical existence representing Redemption and the end of suffering and confusion"(Witkin). As God created man in his image, that must also contain all the little deviance as well. In freaks, in their diversity and potential, Witkin may well find the true face of God and all He represents. In Saviour of the Primates, New Mexico (1982) he portrays a masked monkey strapped to a cross, a skull and crossed bones below. In this, that other face of God becomes apparent. It alludes to animal sacrifice as well as the penitent rites of Mexican penitentes who crucify themselves at Easter. Darker, animal sides of a religion based on love and light.

Witkin’s portrayal of Woman seems like a natural progression from his male Christ. Just as much as God is a large scale creator, so are all woman on a smaller one. Even as Christ suffered, Woman suffered to bring life into the world. "I was trying to create a personal mythological image of the source of all human life"(Celanto, p56). The torture of childbirth is evoked in Mother and Child(1979). A woman holds a baby, both are masked making the picture strange and dissociative. The woman is semi naked but the main interest is the great surgical retractors prying open the mother’s mouth into a scream of pure agony. Pain starts at birth, it is part of the human condition.

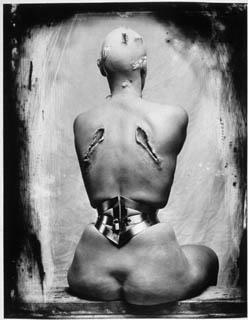

Witkin’s work seeks to illuminate hidden and often primal qualities that belong to all. The horror of Witkin’s images stems not from a wish to shock but to explore. In his own words "I do not make the work to disturb people…I photograph death because it is a part of life! I look forward to dying because I think living on earth, in the plane is one part of existence, and death is another, and that we are constantly learning through the process"(Celanto, p 34). His figures are less personality and more symbol. In Woman Once A Bird (1990) the figure, armless and impossibly belted at the waist, has two great slashes in her back in exactly the place once would expect wings to have been attached. Although the face is not visible and the rest of the body fairly inactive, there is a great sadness to the image. The story reminds at once of a fallen angel, stripped of wings and handed to the dark side. It is now a lyrical vision worthy of compassion. The seeming frenzy of piercing is attempt to allow the individual to become more in tune with their insides. In essence, giving the outside a way into the inside.

Witkin’s work seeks to illuminate hidden and often primal qualities that belong to all. The horror of Witkin’s images stems not from a wish to shock but to explore. In his own words "I do not make the work to disturb people…I photograph death because it is a part of life! I look forward to dying because I think living on earth, in the plane is one part of existence, and death is another, and that we are constantly learning through the process"(Celanto, p 34). His figures are less personality and more symbol. In Woman Once A Bird (1990) the figure, armless and impossibly belted at the waist, has two great slashes in her back in exactly the place once would expect wings to have been attached. Although the face is not visible and the rest of the body fairly inactive, there is a great sadness to the image. The story reminds at once of a fallen angel, stripped of wings and handed to the dark side. It is now a lyrical vision worthy of compassion. The seeming frenzy of piercing is attempt to allow the individual to become more in tune with their insides. In essence, giving the outside a way into the inside.

In the end, beauty is not the image that we are taught but that thing that has the ability to move us on our deepest levels. If Witkin’s images are not beautiful then it is because they are more then that. They have the power to move us to another more open level of thinking. Perhaps the true power in Witkin’s work comes from having the courage to show us the other side of beauty, the other side of ourselves and hence the other side of God. As Christa Palmer has noted "His fascination with the lives of those who live at the margins is not intended to reveal what the individual subject chooses to hide but instead to make the hidden qualities more meaningful". Each image is an answer and then a question. This questioning which leads us to insight that the world is not black and white, that beauty and perversity can and do exist side by side, unified and not to be denied. All the more real

Bibliography

Celant, Germano (1995) Witkin, New York, Scalo

Palmer, Christa (1997) ‘A History of Truth’, Metropolitan, October.

Isola, Marina (1997) Beastly Beauty,