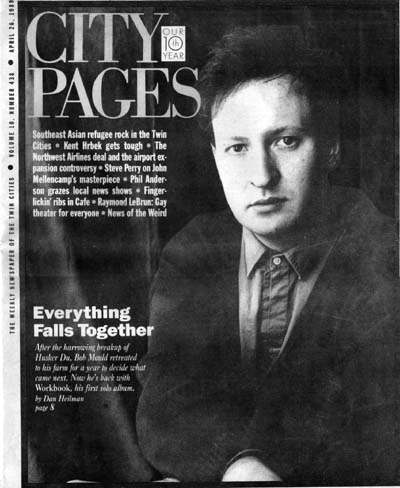

| CITY PAGES (MPLS) - April 26, 1989 |

|

|

M y experience with Bob Mould provided an instructive affirmation of the axiom maintaining that music and musicians would get along just fine without record companies. Not that Mould's label (Virgin, which will be releasing his solo debut album Workbook next Tuesday) wasn't entirely cooperative; but after several phone calls to the label's publicists netted a handful of I'll-see-what-I-can-dos, out of the blue came a call from the artist himself, and in five minutes, the wheres and whens of the interview were established; Mould later said with some pride that his people at Virgin have praised him for being one of the more "responsible" musicians they've dealt with.And aside from being an accommodating guy, Bob Mould is probably the Minneapolis musician most primed to be a national cause celebre right now. Mould left Husker Du, the already legendary Minneapolis trio, last winter, and they, along with the Replacements (with whom they were endlessly - and senselessly - lumped together), Prince, and Flyte Tyme, were regularly the first four artists mentioned whenever discussion turned to the "Minneapolis sound." But the Huskers are the only one of those four entities to have packed it in, leaving a sizable space in the realm of local music superstardom to be refilled. Workbook is no star turn, though; it is the measured, unnervingly |

Workbook ought to come as something of a shock to those who'd grown accustomed to the distortion-drenched hit-and-run style of Husker Du. The record's meditative tone is set by its opening track, a soft-as-a -whisper guitar instrumental called "Sunspots;" for that matter, the album is several minutes old before the first hint of distortion dares reveal itself, leaving Mould's urgent, resonant vocals as the sole point of identification. But by no means does Workbook soft-pedal the emotional intensity that Mould perfected with Husker Du - if anything, the stakes are raised, and lyrically, the record is as harrowing a mix of serenity and savagery as anything since John Lennon's notorious post-Beatles bilefests.Mould wrote all the songs in the privacy of his farmhouse, and that, along with his tentative plans to quit making records, gives a lot of the songs on Workbook the feel of private diary entries. The isolation and anonymity of the area proved to be crucial to the album's creation. "Nobody knew who I was up there," he says. "And nobody down here really knew where I was, and that made it easy to open up without being distracted by going to the bar and talking with friends about it. All anybody knows up there is I have the biggest house in the area and I have a lot of strange friends that make corrugated tin sculptures on my lawn." |

|

New Day Rising After leaving Husker Du, Bob Mould Took a year off to make the record of his life. By Dan Heilman |

||

|

quiet product of a full year's reflection by Mould on the breakup of Husker Du and on his own future, which for a while, looked likely to exclude music. In the 15 months since Husker Du's breakup, Mould, who's now 28, has found some measure of peace living on a 10-acre farm near Hinckley, where he spends his time writing and tending to a yard full of chickens. "There was a job open at the Northwest Company Fur Post," he recalls with a laugh. "It's one of the Minnesota Historical Sites, not too far from where I live, they were looking for a site manager. I thought that'd be great - I can work five months out of the year, and put together slide presentations and touring shows and stuff. And actually, a lot of people said I should take a year off, and that people wouldn't forget me, and damned if they weren't right. But after I started playing these songs for a couple of friends, they said, 'Look, don't get a day job. You should get back into music.' This stuff's pretty important." |

But the most important move for Mould was to divorce himself from his past, at least for the time being. "When I left the group, I was pretty tired of music, generally," he says. "I just wanted to write for myself. I just thought I'd sit up at my farm and write some songs for myself, and maybe someday I'll play 'em. So I was just writing things that I wanted to hear." "I wasn't really thinking about the past or the future or what people would think of it, which to me makes it a really interesting record. It's a real clean start, because I didn't hear any music last year. It was interesting, completely extracting myself from a situation I'd been in - it was like, 'My god, I've gotta get away from this for a while and figure out who Bob is, instead of who Bob from Husker Du is.' I already knew who he was, and I didn't like him anymore." |

|

|

|

"Immediately, everything was back on our shoulders," says Mould. "A lot of the problem with Husker Du was that claustrophobic attitude where nobody from the outside could get in. So now, not only did the only person 'in the band' who was not in the band die, but now we've gotta go back out on the road and keep doing it. The whole thing didn't hit me until June when we were in Europe. I just went into a black hole. I thank the Lord that I quit drugs and drinking two years before that, and that I could hold onto my sobriety through all that, because it wasn't real easy. All I could think about was, 'If this is what it's come to, I don't know if I enjoy it anymore.' It was killing all of us in one way or another - slowly, quickly, spiritually, or physically." Husker Du's last concert was on December 12, in Missouri. "It was just a really bad show," Mould recalls. "Things were not right in public and I don't put up with that. People can call me an asshole and a dictator - Goddamn right. I'm not getting up on a fuckin' stage with all that shit on display. When people are having problems and you're not enjoying what they're doing, you don't do it in front of people, period. It's not fair to people who pay money to see a band. I thought it was miserable, Greg thought it was miserable, Grant didn't know what to think." "To me, the only thing holding the group together for the last two or three years was the music. We just all grew apart, and people can say it's because of girlfriends, or because people are assholes, or people have drug problems, or whatever. Bands break up all the time - the truth of the matter is we grew apart as people and we had nothing in common but the music, and when that ceased to be an enjoyable thing, we had no reason to be with each other." After the disastrous Missouri show, the band cancelled their last two gigs and came home. Warner Brothers, for whom the band had recorded only two of a contractually-promised seven albums, urged them to try to straighten things out. "We were supposed to go into Paisley the second or third week in January," Mould recalls. "I'd spent a lot of time with Grant at his folks' house trying to talk through all the problems, and at that point it wasn't important for me to keep the band together - it was important to me to see Grant get better, and just for everything to get resolved. I thing Greg was more frustrated; he was like, 'Well something's gotta happen...' Then one day, I just woke up and said, 'I know what's gonna happen.'" After the band came to a consensus about dissolving, Mould retreated to his farm while Hart talked about forming his own band and gave his account of the breakup in a Spin feature article. Without the burden of having to write for the next Husker Du album (the songs slated for Paisley Park, Mould says, have been "burned"), Mould spent the first half of 1988 writing songs he was shure would never see the light day, many of which wound up on Workbook. The time off also gave him some desperately needed distance from - and philosophical perspective on - the band that had constituted his entire musical life."My analogy for the band at the time was that it was a runaway train," he says. "Everyone was trying to steer it and keep it on the tracks. Finally we went all the way up the big hill and all the way down it, and when the train got to the bottom I had to get off. I wasn't proud of the band when it ended. But I'll tell you, friends run tapes by me all the time and say, 'You've gotta hear this tape - it's like a Husker Du steal!' And a lot of these bands really have that sound down, and more power to 'em, 'cause it's a great sound." "I don't know how familiar you are with Chet Atkins," Mould says while trying to explain the conceptual reasoning behind Workbook's title. "Have you ever seen his Workshop album? There's a picture of him on the front in his studio, and the liner notes are really cool - he says, 'I don't like being in big studios because people don't dig my work, and I don't dig being around 'em. And it goes on about how Chet has his lonely room that he does his work in. And when I looked at that record, I thought, yeah, that's where I've been for a year. It's like a book to me. I'm the character in the book, and these are my stories, and the events that went on around me. It's pretty personal record; sometimes I have trouble listening to the songs." |

gives off the chilling effect you get when you see something you know you shouldn't be seeing. Some of the songs, like "Brazilia Crossed With Trenton" and the brutally frank "Poison Years", don't require much analysis before they reveal themselves as purgings of old demons: "The more I think, the less I've got to say /I don't remember you no more/About these poison years: it's just a memory." It should come as no surprise that many of Workbook's most affecting songs hearken back, however obliquely, to Husker Du; as the band's self-appointed archivist, Mould still keeps a mass of band posters, reviews and tickets stubs, just to remind himself that there were some great times. But the record was still essentially a product of self-imposed isolation. "I think a lot of what I was going through was in being torn between going to the press and running my mouth about what had happened, and just cooling it," Mould says. "I thought, it's really not fair in a historical sense to add fuel to the fire that had been going. I just thought, 'Well, I'll just sit and work this one out myself.' And there were some songs I wrote that would not be appropriate to put on a record, some things that were really personal." Mould knew he would need some goading to get the songs heard; enter Anton Fier, sometime session drummer (Herbie Hancock's "Rock It"), bandleader (The Golden Palominos), and producer (Joe Henry's new album, Murder of Crows). Last summer, Mould renewed a long friendship with Fier by indicating that he might be interested in recording again. After Fier pledged to help, he spent time at Mould's farm, listening to hours of material and talking about who else should round out the band. Around Thanksgiving, after sifting through dozens of offers, Mould decided to record for Virgin and alerted Fier that work was about to begin. A longtime Pere Ubu fan, Mould told Fier that he'd like that band's bassist, Tony Maimone, to join in; within fifteen minutes, Maimone had cancelled his engagements for the following weeks and called Mould. Acclaimed cellist Jane Scarpantoni was added, and in Mould's words, "It was like, instant band." Mould found that not only had his playing skills been dulled by endlessly performing the same music on the road, but that his mettle as a producer and arranger would receive its first real test with the seasoned pros he'd assembled for Workbook. "When everything's turned up loud, and you're jumping around and everybody's going nuts, it's really easy to play three chords," he says. "But these people... I mean, everybody paid so much attention to detail - like the hi-hat should come in here, and be miked this way - it was like, let's see how much of a producer and arranger Bob is, 'cause these are some badass players, and they're calling my shit up. So it was really challenging." The time elapsed from the start of sessions for the basic tracks to the day the master tapes were delivered to Virgin was just over two months, an incredibly swift pace by latter-day standards. "It was mostly a matter of a lot of 20-hour days," Mould says. "We pretty much locked the door and stayed in there until it was ready." Mould achieved another coup of sorts when he was able to get the core of the band (Fier and Maimone) along with a second guitarist in the dB's Chris Stamey, to go with him on a tour that starts this Sunday in Hoboken, New Jersey and winds it's way through 16 dates, including a homecoming show at First Avenue |

|

A fter a gloriously dense eight-year career resulted in eight albums and countless nerve-fraying barnstorming tours, Husker Du called it quits in January 1988. For Mould, the breakup constituted the end of a long, dizzying odyssey. Mould's childhood in upstate New York was normal enough - his parents ownned a corner grocery store - but after moving to St. Paul and studying at Macalester, mutual friends introduced him to Grant Hart and Greg Norton, and Husker Du's fabled buzzsaw sound was born.The overriding reason for the breakup passed around among insiders focused on drummer Hart's substance abuse problems, but Mould, Hart, and bassist Norton all realized that it was time to step of the merry-go-round. (Neither Hart nor Norton could be reached for this story; Hart released an EP, 2541, last summer, and has played some well-received shows at 7th Street Entry, and Norton is reportedly out of the music business.) Although he realizes it's a story he'll have to tell a hundred times in the coming months, Mould still gets choked up when discussing the band's dissolution. "I was the one who called Greg and said, 'I've had enough. I quit,' and I finally tracked Grant down a week later and said, 'I can't take this anymore, its killing me. It's killing all of us,'" Mould remembers. "Nobody can really take the credit or the blame for it. It had just disintegrated to the point where someone had to stand up and make it formal. When you're in our position, there are people who have to be called, like lawyers and record companies; contracts have to be dissolved. Nobody seemed to want to do that while everything was tumbling, so I just took the initiative and got it over with for everybody's sake." In terms of visibility, Husker Du was at its peak when they began to disintegrate: They were touring to support an acclaimed double album (Warehouse: Songs and Stories), they'd gotten prime exposure on two important, if incongruous national TV shows (Joan River's defunct talk show and an instalment of the Today show broadcast from the Hennepin County Government Centre), and they had studio time booked at Paisley Park for early 1988. But while things came to a head for the band in December, the beginning of the end was the suicide of the band's ad hoc manager, David Savoy, in February 1987. |

|

on May 15. And to answer the inevitable question, "I'll probably come out after the first set and do a compendium of my old stuff, by myself; I wouldn't feel right asking other musicians to play Husker Du songs." Another function of Mould's year off was to assert himself as a producer (for the Zulus, whose album is due for release on Slash, and for Hoboken's Friction Wheel) and record company magnate. Last year Mould co-founded SOL (for Singles Only Label) as a reaction to the escalating policies of major labels of phasing out the seven-inch, two-song single. "It just seemed like something to do," he says. "I mean, I grew up with singles-- my dad would bring jukebox singles home from the store when I was six years old. I hate to see 'em go, because not only did they seem like a big part of my life in '65 and '66, but also in '77 and '78, because then, you felt like you were really helping a band by buying their single, even if you'd never heard of them." SOL already has its first batch of singles out (by new artists like David Postlethwaite, Angel Dean, and the Zephyrs), and now Mould would like to get deeper into producing, an arena in which he's already know as something of a task master. "I take that real seriously," he says. "I don't do one of these put-your-feet-up-and-roll-a-doobie jobs. I do everything: make sure the budget stays within reason, that people have hotel accommodations, the people's girlfriends have a way to the studio... It's a lot of work - you've gotta be a bit of a diplomat and a bit of an asshole. I'm a slave driver, too, and that doesn't come as a surprise to anybody who knows me. I tell them, 'By the end of this you'll probably hate me, but we'll have a good record.'" |

|

|

|

back that's for sure. I was a fool to think I could ever stop." "And one thing I'm really proud of on this record is I finally feel like a writer writer, because I think I was able to do what good writers do traditionally in the romantic sense of the word: They force their work to come out of their environment, and that's what the record signified to me. It was a proud moment for me, because I finally feel like not a songwriter, but a writer." So consider Workbook Chapter Nine in Mould's musical saga; or more to the point, Part Two, Chapter One. And as reluctant as Mould is to go into any detail about the dissolution of Husker Du, he knows that the other principals in the band have gone or will go on record with their stories, and he's content to let that part of his history stay in the past. "When I left the group, I sort of left that where it lay. Grant called me a while ago and told me how his stuff was doing, and I was really happy for him, and I wished him the best, then and now, as I do with Greg as well. But I don't really see the guys anymore; I think it's probably better that way. I certainly don't have any hard |

feelings, but as time goes on, I don't have any feelings at all about it." Mould laughs at the mad-doctor sense his words convey. "Some of the stuff I'm working on now really does take this record one step further, though. I guess it makes me happy, ultimately, to get the poison out of my system and to get the demons out, even if it seems like for every one I get rid of, there's 10 more. But that's fine; that's what I do." |

|