| The Guitar Magazine (UK) September 1998 |

|

|

|

|

Hüsker Düde |

|

|

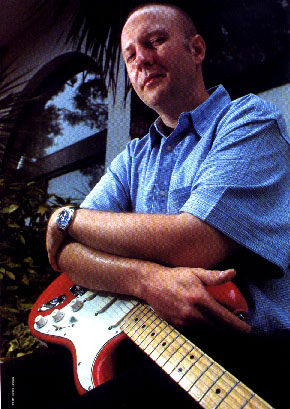

Reluctant 'Godfather of Grunge' and mentor to everyone from My Bloody Valentine to The Pixies to Nirvana to the Smashing Pumpkins, the impact of Bob Mould's raging, tune-conscious guitar fury on modern alternative music is profound. Through the '90s he's moved from gold-selling power trio Sugar back to solo artist - but now he's contemplating leaving theloud stuff behind, forever... |

If you've ever caught Bob Mould on stage in full electric flow, whether fronting Hüsker Dü or Sugar or performing his own solo work, then you've witnessed a man exorcising demons of black-souled fury through the power of sound. The maelstrom of moving air Mould produces as he stomps and strides around the stage - tangible, rolling masses of volume that snaps heads back, thumps chests - is little short of eviscerating. Take, for example, the show Sugar delivered at the Brixton Academy during the London stop on their notoriously noisesome Beaster tour in 1994. The levels were relentless but had a near-spiritual power, a force that seemed almost capable of lifting people up over the balcony railing and tossing them puppet-like into the crowd below. Loud? Definitely. Painful? Er, yes - all those stacked Fender Concerts and Roland JC120s added up to an almost astronaut-in-training G-force effect. Suffice to say, Bob Mould knows how to crank it.

But now he's prepared to give all that up. As the title of his tunefully blistering new solo album The Last Dog And Pony Show hints, the upcoming full-band tour will be the final time around for Mould's full electric rock'n'roll circus...

'It's been great,' says Mould, qualifying his decision, 'but I've been doing it for almost 20 years. I don't feel, like, 'Oh, it's time to go away' - but I do think it's time to maybe put some closure on that chapter of my life.

'By the time I get to play the UK shows I'm going to be 38, which isn't old - but it's not 23, you know, ha ha! I don't want to be saying to myself, 'Wow, when I'm in my mid-40s I'm still going to be up there doing this!' I'm not going to be able to do what I used to do, and I don't want to tarnish what people have perceived me to be over the years. I don't want people to come and pay to see a show, and when I drop my pick on stage some guy has to come out and pick it up and put it back in my hand.'

Indeed, the road, the playing and the volume have all taken a physical toll on Mould. There's his perpetually bad back, the tinnitus that gets so bad by mid-tour that he has to sleep with the TV on full-blast to drown out the ringing in his head, the cumulative abuse he's dealt his larynx... all these make the 'big show' an increasingly painful proposition. Like the rest of us, the man has aged; his always high hairline has moved a couple thousand hairs further skyward, and he's grown a little softer round the middle than in his lean days of adrenaline-fired thrash with speed demons Hüsker Dü, cuddly even - if the man who torched the foundations of popcore on songs of spite and fury like New Day Rising, In A Free Land and JC Auto could ever be described as 'cuddly'.

'It's just... physically, it's real taxing,' Mould continues. 'And it's very invasive on my life, 'my life' being everything but my career. The most invasive part of it is to keep nine people lock-stepped on the same schedule for a number of months; I can't go home, I can't see my friends, I can't see my family, I can't see my dog. I can't do the things that, as I get older, I see are really important to having a life, instead of just a career. So, you know, I hear people saying, 'Oh, I never got to see Hüsker Dü, I never got to see Sugar!' So this is it: fair warning. After this you get to see maybe the acoustic shows or whatever I'm going to do next, and I don't really know what that is.'

So it's not, as has been rumoured, that Mould is turning his back entirely on live work. 'I love playing live,' he declares with relish, 'but just not for three months at a time. I'd love to come over and do five shows and go home again, but you can't do that with a rock band because of the whole circus of getting it on the road. The whole show is just too big; it becomes all-consuming. But you know, I'll still be doing the acoustic shows - and generally a proper, sit-down acoustic show is, I think, even more intense that an electric show.'

Indeed; witness the man drenched in perspiration and close to tears after belting out The Slim or Hardly Getting Over It accompanied only by his Yamaha APX12 acoustic 12-string and you know he's investing as much emotional firepower on the solo stage as he is in the highest-decibel electric band work. But enough idle talk of aging and hair loss... let us indeed, as the man says, rock.

|

|

|

After the all-too-premature dissolution of his last power trio, Sugar, in 1996, Mould hurried back into the studio to record his third, self-titled solo album. The result was a complex and accomplished record but, by his own admission, a dark, miserable, even self-defeated affair ('there wasn't any fun in that record,' Mould now says. 'I wouldn't wish that on anybody!') By contrast, The Last Dog And Pony Show is packed with fun; true, on occasions of Mould's own rather darkly introspective variety, but by any standards a much sunnier, more open outing. You could even call it, if such a word isn't insulting, accessible.

'Accessible? Sure it is! Ha ha ha ha! That's not insulting to me at all. God, it's weird, as the years have gone by it seems like every other record is different: this one's pretty up, then the next one's pretty sombre... I guess it's how I try to keep myself balanced. But yeah, this one, sonically, I'm sorta surprised at how smooth it all turned out.'

'Smooth' is not an adjective generally tagged on to Bob Mould's guitar sound. 'When I was cutting the guitars I spent a fair amount of time looking for the right edge and trying to get that real mid presence,' he explains. 'Then in the mix everything just smoothed out, and I was sorta' freaking out for a minute... then I was like, 'Well, you know what, maybe that's just what's happening. The less I try to fight it, the better it'll be.''

It's pretty uncharacteristic for Mr. Mould not to 'fight it', but the results are superb; The Last Dog... has a sweetness and sonic tactility rarely before heard in his previous work, not even in the subtler moments on his relatively mellow solo debut, Workbook, or in Sugar's power-pop masterpiece Copper Blue, or anywhere. Producing himself yet again and playing everything but drums and cello (duties shouldered by Matt Hammon and Alison Chesley) Mould took long-time engineer Jim Wilson back to Cedar Creek studio in Austin, Texas and spent a month whacking down twelve trenchant, tuneful new tracks. To talk comparatively, melodic pop-classics-in-waiting like Taking Everything and Classifieds are closer in sound, style and feel to Copper Blue radio faves like If I Can't Change Your Mind and Changes, but are fresh ventures in and of themselves; not a change of direction, but a worthy step forward.

'On a technical note, I tried a lot of different amps and also tried using no equalisation on anything - in the cutting there's absolutely nothing, just getting the sound straight to tape: mic, to mic preamp, to a compressor, to tape. No processing, nothing.' Mould's guitars still sound big - well, huge - but now they threaten to swamp the vocals or even capsize the entire track less often than before. It's a new approach, and it's paid off. 'It was different for me, yeah... with the hubcap record (Bob Mould) the guitars were pretty processed and pretty edgy. It was a real solid-state processed sound.

'This time, instead of using a wall of amps, I went with select amplifiers for different things; anything from a Fender Princeton to my Roland JC120 heads with a Marshall cab to trying out some old Fender Bassmans to - my new favourite amp - a Matchless 2x12' combo, the Chieftain.' What about the sweet, round sounds of Skintrade - a loping, loose-limbed slow burner midway through the album that just drips Class A valve tone? 'Ooooh, yeah! That's the Matchless,' grins Mould. 'It's too musical for me, almost! All those Class A amps are just so sweet! Some guy just let me borrow it for like a week. I'm thinking of buying a stand-alone head for the tour this fall.'

Whatever privileged place the guitars may receive in the mix, Mould's still not a big fan of soloing - preferring his intros, riffs, hooks and breaks heavy, hard and tuneful, but ultimately rather minimalist. 'Soloing? Eeuuuchh!' he squeals, cringing visibly. 'Very few people in the trio setting have genuinely stood out as soloists; a lot of people have thought they were good - but really there's Hendrix, and that's about it. When it comes to three-piece bands and guitarists who can carry that and still be great soloists, there was pretty much just one guy... sorry, Leslie West, sorry whoever, but you just didn't do it!'

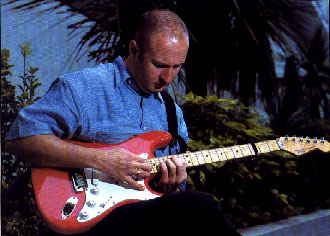

Not a great collector of instruments, Mould is still using the 1987 and 1988 Fender American Standard Strat Pluses he's wielded since Sugar's inception (pretty much standard, apart from the addition of Sperzel locking tuners and Lace Sensor Super Lead pickups in the bridge positions) while for acoustic work he again turned mainly to his Yamaha APX12 stereo 12-string. In the area of distortion boxes, however, he was relatively more adventurous...

'I tried a couple different pedals, because usually I use the old MXR Distortion Plus, the old yellow stomp box,' Mould reveals. 'I was trying some Rats, the Ibanez Tube Screamer - three or four different ones, and they all sounded different - and this other pedal called a Centaur. This guy in Massachusetts makes these hand-made, multi-step-pot distortion pedals, totally hand-wired; he's one of these guys who pours epoxy over the circuit board so you can't see what's happening! They're about $700, and really professional, but it's like 'scary pro' - I really couldn't find much application for it; very adult distortions!'

More than a product of EQ or effects, though, the lush textures on The Last Dog... are mainly the result of careful and correct mike placement, making the most of room acoustics and using the amps as they were designed to be used. 'This album's a lot woodier and warmer sounding,' agrees Mould. 'It's taken some getting used to. The thing that's nice is that it isn't so upper-mid distinct; it's more harmonic and just warmer. It allows for more depth perception in the mix. And I noticed the warmer and more harmonic it was, the more the drums appeared on the direct plane axis as opposed to the wide axis. They seemed

dimensionally deeper because it's just eating up different frequencies in different places.'

Another noticeable change on this album is - oh, wonder of wonders - you can actually hear the vocals in most places. Even on Sugar and Hüsker Dü's poppier numbers, Mould's vocals always battled for attention in the mix with distinctly forward guitars (don't even try to work out what's happening lyrically in the first four tracks on Beaster), but the singing on The Last Dog... has a more distinct position in the aural spectrum without ever threatening to launch a radio-friendly coup on the album's guitar edge.

'I thought the vocals were pretty good on this record,' Mould concurs, 'and I thought they were louder than they were once I heard the record, because we were mixing at low volume and they seemed much more up front - at quieter levels, they're a lot louder.' In places where the guitars do threaten to stomp the singing, it seems that's just the way Mould likes it. 'Generally, it's getting the right balance; the lyrics are included in the record worldwide, so it's not a mystery as to what I'm singing, it's not anything about that! It's just that to me, if vocals are way up then the track suffers, it becomes all about the vocal and all about the lyrics. To me, the vocal is an instrument like the bass or like the guitar. It should sit in the field with everything else, not on top of it.'

Now occupying an un-pigeonholeable class of his own following the less-than-amicable implosion of Hüsker Dü early in '88, Mould's career has outwardly appeared to follow a spiral trajectory of one comeback after another - though these, by and large, are themselves self-imposed via conscious changes of personnel or of musical direction. His popularity has never waned - indeed, he's never really gone away - but there's something about every other Bob Mould album that screams 'I'm back!' - a war cry hollered loudest, perhaps, when Sugar launched themselves on the grunge-dominated scene of 1992, a scene fuelled by Nirvana, Soundgarden, The Smashing Pumpkins and other noiseniks whose sound and stance owed a formidable debt to Hüsker Dü. Talk of 'coming back to the fold' or of his 'Godfather of Grunge' status, however, merely invokes a wry laugh...

'Huhuhuh, yeah, well... I have no choice over those things, but I was more than aware of what was happening, and it was an interesting predicament, to be the returning forefather, and at the same time being aware of all the baggage that came with it... trying to walk that line between being a Nirvana fan but not being a Nirvana follower, and going, 'Wait a minute, Kurt used to come see us in Seattle,' you know...?

'It's like, here's this hot potato,' he continues, tossing rock's stylistic trends - well, a sugar lump - from hand to hand to illustrate. 'Here's Zen Arcade and, whoops, there's (My Bloody Valentine's) Loveless, then here's Nevermind, and over there's Copper Blue. Everybody keeps throwing it around.'

What goes around comes around, certainly, but with heavy guitar rock somewhat on the wrong side of the coin in 1998 and grunge itself almost a dirty word, what sort of a reception can Mould expect for The

Last Dog... ?

'You know, I'm sure some people will look at it and go, 'This has been done, this is sorta tired. We're on to other things,' and I think they'll generally be younger people,' Mould offers. 'But I think there'll be people who are a little bit older and have been around who will look at it and go, 'This is a good guitar record, a good pop record... good songs.' And then I think there'll be that larger group of people who will say, 'This is a really good Bob record. This is what Bob does and this is sorta what we've come to expect.' 'Things come and go, and so much of how popular a record becomes is timing and external forces. You know, at the end of the day I was making this sort of music before it existed. I may make this sort of music after it exists. It's my music, so... ha ha ha!'

|

DÜ RIGHT MAN |

||||

|

|

the tunes could go. 'What The Buzzcocks Following the downbeat and distinctly un-punk yet staggeringly impressive Zen Arcade - a double album which followed a single storyline about a boy leaving home - the Hüskers churned out New Day Rising and Flip Your Wig in rapid succession, discs which clinched the band's reputation as popcore masters and earned them a major-label deal with Warner Brothers. As if to scotch any rumours that they'd sold out to the big boys, Mould, Hart and Norton's major debut, Candy Apple Grey, was as searing and uncompromising as any album they'd made to date. It's follow-up, the double LP Warehouse: Songs And Stories was still redolent of the trio's darker demons but came packed with punchy, From 1981 to the split early in 1988 Hüsker Dü recorded nine albums, two of them doubles; the influence of this prolific output is the stuff of legend. The Pixies recruited bassist Kim Deal through an advert seeking members for a 'Hüsker Dü / Peter, Paul and Mary band', and Black Francis has famously commented, 'When we made our first album I owned four LPs, and three of them were by Hüsker Dü.' In this, he echoed the sentiments of a generation of indie and alternative rockers. |

|||

|

W hen it comes to setting standards for alternative rock sonics, one name bubbles to the top time and again: Hüsker Dü, the trio who coined popcore nearly two decades ago by slashing the boundaries between The Byrds and Black Flag.Formed initially as a hardcore thrash band in Minneapolis, Minnesota, in 1979, with Mould on guitar and vocals, Grant Hart on drums and vocals and Greg Norton on bass, Hüsker Dü were - even in the burgeoning local punk scene - the wrong kids from the wrong part of town playing the wrong music. 'We didn't fit in with the bands in Minneapolis at that time; we were very disliked when we started,' Mould confesses. The rebellious trio pushed their sound to extremes of speed and aggression; the results were explosive - and the rock world feels the shock waves to this day. |

Before long Hüsker Dü were pioneering a movement, garnering adulation from fans, lodging in every rock critic's 'top 10 of the year' list and sending journos scrambling for their thesauruses in search of new superlative synonyms for 'fast' and 'heavy'. But while the power and pace of the band's early sets got people's attention - see the live debut LP Land Speed Record (1981) and its follow up, Everything Falls Apart (1982) - a far more revolutionary tendency was bubbling under between the dual songwriting powers of Mould and Hart: these guys could actually write tunes. The collision of hardcore thrash with luscious pop melodies was consummated on the seven-track mini-LP Metal Circus (1983). Raised on a diet of The Beatles, The Byrds and The Who, Bob Mould was well grounded in pop sensibilities by the time early punk bands like The Buzzcocks came along to show him where |

|||

|

BOB MOULD THE LAST DOG AND PONY SHOW (Creation) Others hint at future directions; take your pick from the cello- accompanied lament Along The Way (fine) or sample-driven 'electronica' Megamanic (awful). Elsewhere, Mould's tiredness is manifest, First Drag Of The Day particularly being forgettable Bob-by-numbers. So, more a final hurrah for the old than a hearty blast of the new, The Last Dog And Pony Show lacks the vigour last heard over five years ago on Sugar's Copper Blue and Beaster yet, reliably, it is another decent Bob Mould album. Given his immense influence on post-punk American guitar music, it would be foolish to write Mould off just yet. 3 stars (out of five)Michael Leonard |

|