| Select Magazine (UK) - November 1990 |

HUSKER DU - Goodbye to the Metal Circus.

Husker Du roared out of Minneapolis in the early '80s to become one of decades most influential guitar bands.

A power trio of Bob Mould (guitar/vocals), Greg Norton (bass/vocals) and Grant Hart (drums/vocals), they made seven classic albums before imploding at the beginning of 1988. It was a legendary hard-core fallout between Mould and Hart and heroin.

Norton now sells donuts but Mould and Hart are pursuing solo careers. And the bitterness lingers on.

This is their story...

SHEER HART ATTACK

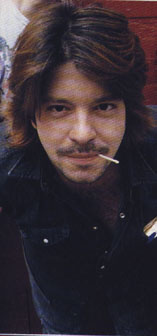

Almost two years after the end of Husker Du, Grant Hart is still a bitter and resentful man. Now free of a destructive drug habit, he's starting over with his own group.

Story by Nick Griffiths.

In January 1988 following a widely publicised period of heroin addiction Grant Hart quit the US' most influential and revered hard-core band. Husker Du. The band split.

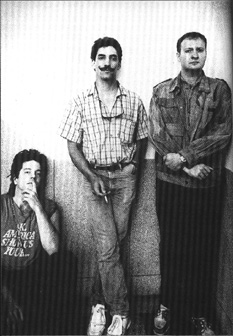

Formed at the beginning of the 80's in Minneapolis the Huskers were a powerhouse trio: Bob Mould (guitar/vocals), Hart (drums/vocals) and Greg Norton (bass/backing vocals). From 1981's live 'Land Speed Record', a frenetic blow of unfettered thrash. They developed their style in a further six albums, culminating in the introspective and hook-loaded 'Warehouse Songs and Stories' (1987).

Both Mould and Hart have since gone solo. And Greg Norton? The waxed-mustacioed bass player now runs a doughnut stand on the boardwalk in Atlantic City.

The demise of the band was inevitable. Bob Mould and Grant Hart were joint leaders of the outfit, but Mould had gradually been curtailing Hart's creative input by giving him less songwriting space on each album. The final straw came when Mould autocratically cancelled the last date of the 'Warehouse' tour. The tension that had prevailed for some time snapped.

The vicious war of innuendo that ensued between Hart and Mould is now legendary.

Mould released his solo 'Workbook' LP on Virgin America in July '89, followed by this year's 'Black Sheets of Rain'; Hart released 'Intolerance' on Husker Du's old label SST in November 1989 and played UK dates with his new band Nova Mob, in the early summer.

The records garnered lavish critical praise and both men departed from the harsh fuzztones and obligatory guitar solos that characterised Husker Du.

With 'Workbook' and 'Intolerance' both intense albums, Mould and Hart had reached a low ebb in their lives following an illustrious ten-year career in Husker Du and both sets of lyrics contain subtle sniping references to the other.

Musically Mould's 'Workbook' is a beautifully restrained piece of guitar work, 'Intolerance' has a higher feel to it, tracing Hart's '60s childhood influences with swirling organs and beguiling psychedelia.

But Grant Hart- songwriter, musician, painter, poet, environmentalist --is a man of anomalies. His keyring says "Fuck You" and his appearance suggests aggression, but his conversation is managed and considered. He can be affable, humorous and unpretentious. Not to mention embittered and mistrustful......

To Grant, the memory of the split is still painful.

"It totally destroyed my network. I was left with a bad reputation, and everything else had been taken by the others. I came back after quitting the band and they'd gone through the entire office. Only things that were my direct possessions they'd left. But the computers, all the files, all of that has been out of my reach. So I have to re-establish the network, which is good because it's going to be an up-to-date one."

Network?

"In terms of different agents, mailing lists. So it's like, I was blackballed and then silenced because I couldn't get in touch with anyone."

At present Nova Mob do not have a record deal either here or in the States. Though Rough Trade look interested in the UK, things in America are a different matter. Grant is not considering renewing the contract with SST. He's critical of their accounting procedures and their overseas effectiveness.

"It's like they're almost afraid to sell records in Europe. And they have many people wanting to do pressing and distribution with them but they say (Grant adopts an uppity accent), Well those records won't sell because people want to have the original issue.

"Plus they're paranoid as hell about anybody getting their fingers into the SST pie."

"I love the people working at SST dearly. But it's like living an old, crippled dog - he can't chase a rabbit.".

He minces words no less when asked whether Warner Bros., the label for the final two Husker Du LP's, 'Candy Apple Grey' (1986) and 'Warehouse', might be interested.

"Warners aren't out of the picture. One problem I do have with them - and you can print this - is the first day that the Warners office was open after Husker Du broke up, I was given reassurances by a person in that company that they would work with me in the future and that they had always wanted to see what I could do on my own.

"And then two weeks later, I got a very official letter in the mail that unless Husker Du get back together then any ties that the individuals may have to Warner Bros. would be severed. And I think some other people formally in the group had something to do with that."

He measures his words carefully, weighing up each sentence before he airs it, but the insinuation's clear - he was stabbed in the back.

The word "Bob" crops up with alarming regularity, rarely in amicable circumstances. After two and a half years, the distrust is as rampant as ever. There's none of this, Oh we'll meet over a pint one day and have a drink and a laugh about it. It's more....

"There's a little part of me that wants our T-shirts to be a dollar cheaper than his."

He blames Husker Du's split not on his heroin addiction but on not being able to trust the people he was working with. Would things have been different had he not been on drugs?

"No things would have been different about the drugs if I hadn't been in the band."

Was it pressure from Bob or Greg that forced him to come off the heroin?

"No it was myself. Bob and Gregory reacted like, This was something we never knew about before," he mimics, adopting an air of wide-eyed incredulity.

Grant weaned himself off the drugs with the help of a doctor who treated him as an out-patient, so that he could keep his mind of the rehabilitation by working. Much of 'Intolerance' was written during this period.

"I can see 'Intolerance' as being a very reactionary record. It's relating to things that had been said. I wanted to surprise people by doing this album myself because I had been branded as someone who had been unable to do anything but shoot heroin. I wanted to disprove or at least cause some of these things to be examined."

Given the markedly different style of 'Intolerance' compared to any Husker LP, was he being compromised in Husker Du?

"Completely."

And is that the sort of music he'd rather make?

"Not necessarily rather, but I would like to have had a little more subtlety when subtlety was called for. There's some instances where Husker Du takes a lullaby and turns it into a song for strippers. Every song had to have required guitar solo. It's kind of like burying a sparrow with a bulldozer.".

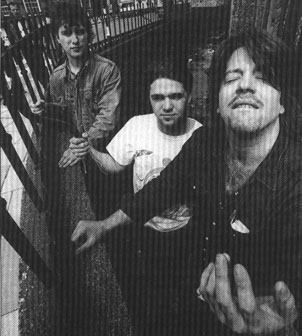

Grant is now working on the first Nova Mob LP, 'The Last Days of Pompeii', loosely turmed a rock opera. He had worked with various band's after the demise of Husker, from Yanomanos and the Strange Men to The Swallows., but not mentally ready for the band scenario, he made 'Intolerance' alone.

With Nova Mob, he's far more at home. Bassist Tom is an old friend from high school and Mark, the drummer, who played with Tom in Harvest House, completes the trio with Grant on guitar and vocals.

He compares 'Pompeii' to the Who's 'Quodrophenia'. It will not be played by a host of stars, but by Nova Mob alone. The story itself is somewhat complicated.

"It starts out narrated by Pliny the Younger from Pompeii, okay?" He pauses, grinning. As the story becomes more abstract, so his grin widens.

"He pretty much gives the general synopsis. The story starts with the fall of Nazi Germany, and Wernher Von Braun doesn't wanna be captured. So he conjures up Wotan, the Nordic god of war and asks him, like, How the hell do I get out of this mess?"

Von Braun then escapes back in time in a V2 rocket, meets Pliny the Elder who takes him to Pompeii, and ends up with King Pompedebile (from the illustrated book, The Knave of Hearts) trying to control his mind, much as Hitler had done before.

Grant takes up the bizarre story again

"He slowly comes to the realisation that he's going to be manipulated, no matter what he does. He leaves again, but it's not altogether clear how. It's more or less a transcendental thing involving the eruption (of Vesuvius) - the eruption wakes him up from a sodium pentathol induced dream."

Weired - but different. Where does the concept come from?

"The theme of control, where he is being manipulated and controlled while being the smartest person around."

Whatever has gone before seems to a strengthened his determination not to compromise. To say the least.

"We have no intentions of just chasing the golden parrott. I'd rather make 20 records that sell a 100,00 copies each than one record that makes two million dollars and destroys my reputation - destroys our reputation."

"When it comes down to it, your physical body, your energy and your reputation are the only things you have to preserve, because you could be flat broke but, you know, play a gig and people will come and see it and you're not flat broke."

Does money worry him?

"No I mean, it would be nice to be doing this interview while shopping or getting a massage, but looking at my life it's not so fucking bad without much money. I have things in my life that Bob will never be able to afford with his money."

That 'Bob' word again....

HERE COMES THE RAINY SEASON

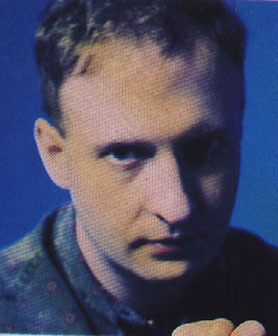

Glad to be free of Husker Du, this solitary man Bob Mould talks about the success of his solo career and how he regrets an acclaimed group coming to such an undignified end.

Story by Graham Linehan (of 'Father Ted' fame - Tony)

It's funny, but in colour, in person, Bob Mould looks much the same as he does in the black and white shot that graced the sleeve of 'Workbook'.

His expression hasn't changed; he still looks simultaneously expectant and relaxed, calm with reservations. And he's still holding a cigarette. When he speaks he taps it into the ash tray, gusts of smoke escaping his mouth with each word. After an hour, the ash tray resembles a small funeral wreath ravaged by fire.

"The last thing I want is for people to listen to the records and come away with, Oh, we really feel sorry for Bob," he says. "The goal is to people to examine whether they identify with the various ways of dealing with the various situations."

Do you use the songs to prepare yourself for the pain,

"Yeah I think so," tap, tap, exhale. "It's part of the healing process, getting those kinds of thoughts out of your mind and allowing yourself to look forward to something again, even if it's a variation on what you've gone through before. You try to document places you've been and trace what kind of an effect that has on your next time round, whether it's the relationship or friendship or whatever."

Do you enter things with your guard up?

"Um, you can't, he laughs. You have to let go let yourself be completely immersed in it... knowing full well that the worst can happen. You have to keep going on. You could never have an amazing relationship without completely giving in. But it's hard. You get torn between, God, I've been through this before... and, God I don't care."

Tap, tap, exhale

Bob Mould's second solo album, 'Black Sheets of Rain', is not an entirely worthy successor to last year's monolithic 'Workbook', but it does feature some of his most wildly electric primal screams since the ugly demise of Husker Du. It's main fault, probably, is that it stretches the mordancy and bleakness of 'Workbook' far past breaking point. Everything's still in black and white. Autumn walking unchecked into winter.

"It's a different album" he say. "It's similar but it's not the same. Thematically it's along the same lines. It's still the rust. But the sonic approach is different. I just chose electric guitars as the main vehicle this time, as opposed to acoustic. And the cello wasn't in my head to this time... I was hearing electric guitars in my head."

It's certainly louder. Was that due you to moving base from Minnesota to Manhattan?

"It had a lot to do with the shading of the record. On the farm in Minnesota everything was very green and very quiet. There was a lot of solitude and natural sound, and when you get thrown into the city your immediately bombarded with constant noise and aggression and speed, and that has to show up in your work."

"You try to compete and coexist with your elements. 'Workbook' was a very outdoor, open-sounding record. This one is the sound of the city in its own way... Not like Lou Reed's album ('New York'), which was very site specific, but more to do with a sense of concrete and steel."

You seem to put yourself in places where you don't feel that comfortable.

"Well, once you get too relaxed in a place - as I was in Minnesota - you get a lot less inspired. The less difficulty there is, the less there is to contend with. New York is really exciting, though. Miserable but exciting. There's a lot to take in there. And there's a lot of conflict; racial conflict, class conflict."

"It's interesting, watching the decline of a major metropolitan city, being there to witness that..."

How do you deal with the fabled everyday obnoxiousness of New York's inhabitants?

"I'm polite," he says, smiling. "You can freak people out just by being polite."

It's the curse of solo artist. Leave your band, record an album and suddenly everybody's calling you 'mature'. Novelists 'mature', playwrights 'mature'... Surely it's rock 'n' roll's job to regress...

'Mature' is a word you see a lot in Bob Mould reviews. He is now 30.

"Let's be honest, we're all getting older," he says in his soft, gas-flame voice. "I think that year alone I had before 'Workbook' gave me a look at what my priorities were. Of course, I still want to make music but what kind, y'know? Did I still want it to be a thrash thing or what?

"It gave me a chance to get much more of a grip on the terms that I use, the sonic temperament that you have from record to record. So, it's maturing, yeah, but just because something's mature doesn't mean it has to be boring."

Recently, Bob pared down his band to three members: himself, Anton Fier (of The Golden Palaminos) on drums and Pere Ubu bassist Tony Maimone. He doesn't feel much need to baptise the unit unless you count the current working title of The Bob Mould band.

"I never felt comfortable being part of a group," he explains. "I'm not necessary talking about that in the band sense of the word. I'm cynical about people who base their complete lives around groups, who feel that their lives aren't complete unless they're part of something. I get scared of group mentality."

He sighs. "America especially is so orientated that way. It's not individualistic. People really want to belong... to a fashion statement, a political group or a religious thing. I find it very frustrating. I like being alone. I don't like being part of a gang."

Were the seeds of the feelings sown when Husker Du were still together?

"Yeah, and in the old days it was supposed to be a democracy where everybody had an equal say in everything, and as time went on it became apparent that it wasn't. It was getting very frustrating for me to keep trying to maintain that illusion."

"Now it's pretty cut and dried. With Anton and Tony it's very flexible and good. With the Husker Du situation it was always, if somebody left that was it, nobody could be replaced. So there was always that hanging in the back of your head . Now, everybody knows that if by the end of all the touring we look at each other and relies it's not that much fun anymore, we can all walk away and not feel lost."

"In a sense, there's more equity. We're playing this music and that's all there is to it."

Husker Du collapsed under a weight of backbiting and in-fighting. Grant Hart, the band's drummer and second songwriter, even included a song on his LP, 'Intolerance', which appeared to be addressed to Bob. It was entitled 'You're The Victim'.

'Yeah, ah, ha, ha, ha. I heard the album once ah, ha, ha, ha,... I thought it was funny. It was the album he wanted to make, that's all I can say about it except... I'm glad that Husker Du broke up."

Are you happy about the band's legacy?

"Seems like the guitar band thing is really back," he says, squeezing his thousandth cigarette butt to death. "Whether it's the Dinosaur Jr type or some of these English bands. The whole experience of Husker Du was great...

"It's unfortunate that it soured as it did, and because that souring aspect of it was harped upon by other people in the band so much, it just made me want to reject it. When you've got people you used to work with either badmouthing you or the experience, you end up feeling that way. But now, with the distance, I can appreciate it more. I thought it was a great thing, it's just a pity we didn't try to solve our personal differences until it was too late."

Did the friction in the band help the music?

"No, it's got very ritualistic. By the last album it had just gotten stagnant. It was the same as the three albums before it. It didn't progress much, and that's a good time to stop. I think if Husker Du had made another album it would have been terrible."

'Husker Du might be important still to a lot of people in the sense of music history, and I'm flattened by that, but it doesn't affect my life anymore. As regards the fighting, I said all I had to say in the nine years the band was together."

Did the split leave a large gap in your life?

"When I left the band in January of '88 making music in public was the last thing on my mind. I really wanted to get out of the whole thing. I'd gotten sick of the business, gotten sick of the routine of constantly touring, gotten sick of never having a private life, never having time for myself. So I just withdrew from the whole thing and spent a year just writing music, for myself with no real intention of making a record, or some kind of statement, or anything."

"Then it's sort of snowballed and friends started asking when I was going to start making music again. I sent out a demo and the response was amazing. Every label in the country seemed ready to do a deal. So I settled on Virgin and did the album."

"But I made the record for me. I knew people have certain expectations so I wasn't too optimistic about the response, but I didn't care. So when the response was so good, it came as a shock."

"Workbook' will always be a special album to me because... I don't want to make allusions to anything silly but... There was the stuff before 'Workbook' and the stuff after. 'Workbook' was like a fulcrum. And things are gonna change again soon. They have to."

Life is being good to Bob Mould at the moment. He has his music, his cigarettes, a city to look at. And things are going to change soon. As the man said, they have to.

Tap, tap, exhale.