In Conclusion

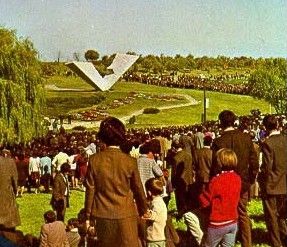

Memorial

Park in Kragujevac has been visited by millions of people

in the last two decades. Annual events are held there

every year and many schoolchildren take excursions to the

park to learn about their country's history.55  Memorial

Park and its monuments were even featured as main

attractions in travel brochures for Kragujevac.56 Thus the

messages inherent in the monuments and inscriptions at

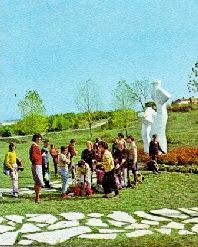

Kragujevac have reached many. Stjepan FilipoviŠ's image,

his arms outstretched in a victorious "V," is

one of the most familiar in Yugoslavia and has graced

many museum walls and publications about the war.57 The

presentation of these two events does have a

powerful impact on the public synthesis and formation of

historical consciousness; however, the perception of the

beholder must also be taken into consideration. A person's

perception of the past may be manipulated to some extent

but loyalty, grief and other basic human emotions are

less susceptible to outside influence. Memorial

Park and its monuments were even featured as main

attractions in travel brochures for Kragujevac.56 Thus the

messages inherent in the monuments and inscriptions at

Kragujevac have reached many. Stjepan FilipoviŠ's image,

his arms outstretched in a victorious "V," is

one of the most familiar in Yugoslavia and has graced

many museum walls and publications about the war.57 The

presentation of these two events does have a

powerful impact on the public synthesis and formation of

historical consciousness; however, the perception of the

beholder must also be taken into consideration. A person's

perception of the past may be manipulated to some extent

but loyalty, grief and other basic human emotions are

less susceptible to outside influence.

Now, in

contemporary Yugoslavia, geographically truncated by

another civil war in 1991, the political tide has shifted.

Communism, though still nominally present in Now, in

contemporary Yugoslavia, geographically truncated by

another civil war in 1991, the political tide has shifted.

Communism, though still nominally present in  Yugoslav politics,

has faded. In its place, nationalism has arisen and,

though all of the parks I visited (most of which are not

discussed in this paper) are still cared for and open,

there are many indications that Tito's "program"

and the preservation of a pure Partisan memory is no

longer a priority. Many museums that I intended to visit

were closed, especially those concerned with Tito

specifically. The museum of the "revolution,"

as the Second World War is called in Yugoslavia, had been

closed indefinitely due to lack of funding. "Eternal

Flames" had been dedicated at Kragujevac and Valjevo

under Tito, but these have long since been neglected.

They sit, somber, their flames long since forgotten.58 This

testifies to the fact that Serbia is in a state of

transition and her monuments reflect this. Yugoslav politics,

has faded. In its place, nationalism has arisen and,

though all of the parks I visited (most of which are not

discussed in this paper) are still cared for and open,

there are many indications that Tito's "program"

and the preservation of a pure Partisan memory is no

longer a priority. Many museums that I intended to visit

were closed, especially those concerned with Tito

specifically. The museum of the "revolution,"

as the Second World War is called in Yugoslavia, had been

closed indefinitely due to lack of funding. "Eternal

Flames" had been dedicated at Kragujevac and Valjevo

under Tito, but these have long since been neglected.

They sit, somber, their flames long since forgotten.58 This

testifies to the fact that Serbia is in a state of

transition and her monuments reflect this.  The monuments and

museums that once played such a crucial role in

preserving and flattering the Partisan legacy are slowly

becoming expendable. Propaganda, no matter the degree of

subtle finesse invested, has a short shelf life. The monuments and

museums that once played such a crucial role in

preserving and flattering the Partisan legacy are slowly

becoming expendable. Propaganda, no matter the degree of

subtle finesse invested, has a short shelf life.

The

massacre at Kragujevac illustrates both continuity and

change very well. The fifty years following the massacre

have not altered the gravity or the cruelty of the event.

In fact, most people have difficulty even comprehending

such a tragedy because they lack a frame of reference for

a massacre of that magnitude. Before World War II, there

was no precedent for such a massive slaughter and now,

two generations removed from the tragedy, we again lack

the memories to comprehend such an act. The  unalienable fact

is that we all acknowledge the tragedy and, as we are

restricted by mortality ourselves, to even try and

imagine such an inane event forces us to draw a sharp

breath and ponder our fragility as humans. And for most,

it is simply impossible to understand what madness was

behind such a disastrous event. What were the gunmen

thinking as the spent all day murdering? What prompted

Boehme to order such a harsh reprisal? Did he have any

concept of what his order would mean? We are all together

asking these questions. As individual humans, stripped of

all sense of military or political affiliation, we

respond similarly to the Kragujevac October. We all feel

the loss that pervaded "A Bloody Fairytale."

And this sense of sadness is timeless and indiscriminate.

The continuity of Kragujevac is in its timeless tragedy;

the change can be found in our fleeting ability to truly

comprehend the execution of 5,000 in two short days and

in Tito's passive manipulation of Memorial Park. unalienable fact

is that we all acknowledge the tragedy and, as we are

restricted by mortality ourselves, to even try and

imagine such an inane event forces us to draw a sharp

breath and ponder our fragility as humans. And for most,

it is simply impossible to understand what madness was

behind such a disastrous event. What were the gunmen

thinking as the spent all day murdering? What prompted

Boehme to order such a harsh reprisal? Did he have any

concept of what his order would mean? We are all together

asking these questions. As individual humans, stripped of

all sense of military or political affiliation, we

respond similarly to the Kragujevac October. We all feel

the loss that pervaded "A Bloody Fairytale."

And this sense of sadness is timeless and indiscriminate.

The continuity of Kragujevac is in its timeless tragedy;

the change can be found in our fleeting ability to truly

comprehend the execution of 5,000 in two short days and

in Tito's passive manipulation of Memorial Park.

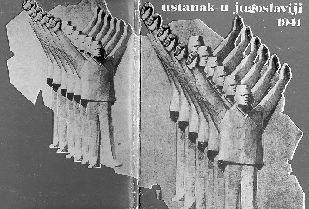

The

emphasis on victory in the name of Socialism and the

glorification of defiance present in the monuments at the

park speak to the masses to remind them to whom they

should be grateful. Critically considering the latent

messages in the park is not denying the Partisan

contribution to the war effort; it is simply recognizing

the Partisan program to create a glowing picture of their

bravery. Tito dutifully showed his respects to the fallen

innocent, yet he managed to advertise himself and his

political party as well.

History

can be understood on several levels: on the individual

level, and on the group level. The picture changes

drastically when one considers how people respond as a

group. Government is simply a synonym for the phrase

"collective mentality, with rules." Here,

agendas, power intrigues, and loyalties are in transition

and all of them interact with each other on an abstract

level. The result is often a multi-tiered maze with many

dimensions. The historical memories of the Kragujevac

massacre and FilipoviŠ's hanging have many dimensions

and demonstrate concretely the government's attempt to

change historical consciousness. Collectively, people are

vulnerable. And yet, Kragujevac, in its tragedy, and

FilipoviŠ, in his bravery, exemplify constancy as well.

The tragedy of 5,001 deaths will not be lessened over

time: it is a constant.

When

a person is acting as an individual instead of a member

of a group, the poem "Krvava Bajka" is touching

and sad, and Filiopvic's story is inspiring. The danger

comes when one group has the power to persuade, slowly

but surely, a public audience into believing something

that is just few shades away from the truth. Lies that

are close to the truth are those with potency, because

they are more readily accepted.

Continuity,

as I have demonstrated, is in the case of the Kragujevac

massacre and the FilipoviŠ statue, primarily associated

with the individual. A discriminating, rational person

has fewer tendencies to shift and less complexity than a

group. A personal historical consciousness, once defined,

is hard to disturb if a strong emotion or reaction has

cauterized it permanently. However, people in groups are

much more fluid and likely to shift. In large groups,

emotion, the very thing that ties us together, is blunted

and so we are more susceptible to half-truths. Naturally,

if something very important is in question, the

individual is alert and on guard. However, if the subject

in question is not considered a "sacred cow,"

the individual loses definition and blends into the group,

where he can be influenced. Thus, change is associated

with the group.

A

close examination of two case studies has given us

insight into the dynamic relationship between the Serbian

people, their collective memory, and Tito's government,

which played such an active role in the formation of the

historical consciousness in Serbia. The individual, in

tandem with the state and its political agenda, define

historical consciousness.

Yugoslavia

is a crossroads, culturally and geographically, and many

influences have come to bear on its people. Many agendas

have been served on its soil. As in any country, caveat

emptor is a necessary precaution. Critical thinking

is a dying skill in our modern society; our individuality

and sense of truth are easily lost in this age of

technology. Looking into the past gives us the

opportunity to learn and history, as well as the way we

choose to interact with it, can affect our lives in the

present. The truth is worth effort, trial, and

tribulation.

|