A Memory Explored

The park itself is a lovely tangle of

wooded areas and winding, narrow walking- paths that

impulsively open up into clearings. And more often than

not, the clearing is dominated by one or more monuments,

some reveling in their new, white glow, and others

shrinking to ground in their relative dilapidation.

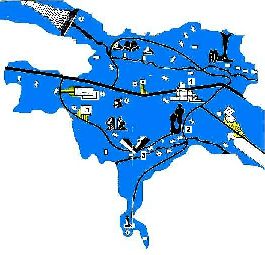

Memorial Park, a two-acre expanse dedicated solely to the

memory of the victims of the 1941 massacre at Kragujevac,

lies on the edge of the city and hosts a large three-story

museum on its western perimeter. The museum stands at the

entrance to the park like a sentinel, guarding the stone

monuments and the memory of the fallen within. There is a

billboard-sized map near the museum outlining the layout

of the park, directing visitors to the various monuments

and park facilities: the library, the hotel, and the

lecture hall.26

The more prominent monuments are drawn in

miniature in their proper places.  The grounds have

a tousled look about them, as if the park is a popular

attraction during the warmer seasons. I arrived on a

beautiful spring day, early in March 1998. The grounds

and the museum were both practically deserted. I found

one sleepy attendant sitting just inside the entrance to

the museum. He was rather displeased at my arrival, as he

had intended to close up early due to the lack of

visitors. However, after I had explained my business in

my best Serbian, his Balkan sense of hospitality came out.

He was amused at my attempt to use Serbian and that broke

the ice. He gave me a guided tour of the museum and

managed to find me a brochure, which was no easy feat

considering the fact that my visit was in the off-off

season. Thus began my excursion to Kragujevac's Memorial

Park. The grounds have

a tousled look about them, as if the park is a popular

attraction during the warmer seasons. I arrived on a

beautiful spring day, early in March 1998. The grounds

and the museum were both practically deserted. I found

one sleepy attendant sitting just inside the entrance to

the museum. He was rather displeased at my arrival, as he

had intended to close up early due to the lack of

visitors. However, after I had explained my business in

my best Serbian, his Balkan sense of hospitality came out.

He was amused at my attempt to use Serbian and that broke

the ice. He gave me a guided tour of the museum and

managed to find me a brochure, which was no easy feat

considering the fact that my visit was in the off-off

season. Thus began my excursion to Kragujevac's Memorial

Park.

Kragujevac October, 1941 is a thin

brochure, complete with color photographs of all the

major monuments in the two-acre park. It contains a brief

synopsis of the events in October 1941 and it also offers

biographical information about some of the victims. The

cover is graced with a photo of the most famous and

poignant of all the monuments: Monument to the Dead

Schoolchildren.27

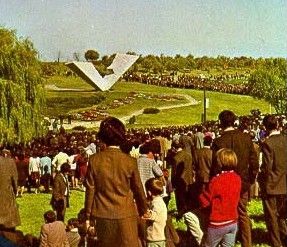

This statue is a very large stone reproduction of

the Roman numeral five. It is commonly accepted that the

Roman numeral symbolizes both victory and the grade of

the class to which most of the child-victims belonged.

Every year, on October 21, "The Great School Class,"

a musical and artistic extravaganza, is held in the  area surrounding

this monument.28 This is

only one of many public events that take place at

Memorial Park in Kragujevac each year. Other monuments

throughout the park are titled One Hundred for One,

Against Evil, Stone Sleeper, and Monument

of Pain and Defiance.29

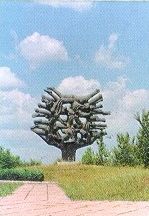

The monuments characterize various aspects of the

massacre. Some, like One-Hundred for One, are

fierce and embody outrage at such a bestial crime. The

ire is of course expressed in the monument itself: layer

upon layer of dead rise high up into the sky on a thick

pedestal. Monument of Friendship explores a

different set of emotions evoked by the tragedy.30 It reflects the sentimental area surrounding

this monument.28 This is

only one of many public events that take place at

Memorial Park in Kragujevac each year. Other monuments

throughout the park are titled One Hundred for One,

Against Evil, Stone Sleeper, and Monument

of Pain and Defiance.29

The monuments characterize various aspects of the

massacre. Some, like One-Hundred for One, are

fierce and embody outrage at such a bestial crime. The

ire is of course expressed in the monument itself: layer

upon layer of dead rise high up into the sky on a thick

pedestal. Monument of Friendship explores a

different set of emotions evoked by the tragedy.30 It reflects the sentimental nostalgia that must accompany such a

tragedy. Other monuments, Monument of Pain and

Defiance, for example, commemorate the agony and

grief the massacre spawned in those who fell in at

Kragujevac, in those who carried on during the war in the

shadow of Kragujevac, and in those who visit Kragujevac

years later to remember. nostalgia that must accompany such a

tragedy. Other monuments, Monument of Pain and

Defiance, for example, commemorate the agony and

grief the massacre spawned in those who fell in at

Kragujevac, in those who carried on during the war in the

shadow of Kragujevac, and in those who visit Kragujevac

years later to remember.

It is interesting that a monument

was erected to pain and defiance. "Defiance"

is the usual element. The park stands in memorial to a

massacre of massive proportions that was directly

triggered by defiance. The very trigger of the

massacre, excluding German complicity, is thus being

commemorated.  There is reason to memorialize the

fallen, but it seems that those who commissioned the

monument feel the need to justify their actions. Are the

Partisans perhaps a little defensive about their role in

the Kragujevac tragedy and the Second World War in

general? Objectivity becomes very difficult, as many of

the facts have been obscured by Tito's interpretation of

historical events during the war. The perspective and

interpretation that have survived in the historical

consciousness of the Serbian people are those of Tito and

the There is reason to memorialize the

fallen, but it seems that those who commissioned the

monument feel the need to justify their actions. Are the

Partisans perhaps a little defensive about their role in

the Kragujevac tragedy and the Second World War in

general? Objectivity becomes very difficult, as many of

the facts have been obscured by Tito's interpretation of

historical events during the war. The perspective and

interpretation that have survived in the historical

consciousness of the Serbian people are those of Tito and

the  Partisans. Schoolbooks, television

programs, museums, monuments, all of these things serve

first to shape and, later, to proliferate, a certain

historical consciousness. The process at work is best

defined by one popular cliche: History is written by the

victors. A world of wisdom exists in that simple sentence.

In this situation, conflict is at issue. When conflict

occurs among people and a battle ensues, there is always

a winner and a loser, even if the status is relative.

There are always two (or three or four...) sides to every

story and the "victor" will pick the "version"

that is passed on to future generations. The victor will

be, of course, tempted by the desire to justify all of

his doubtful acts; thus, history with a distinct slant is

handed down as absolute fact. Partisans. Schoolbooks, television

programs, museums, monuments, all of these things serve

first to shape and, later, to proliferate, a certain

historical consciousness. The process at work is best

defined by one popular cliche: History is written by the

victors. A world of wisdom exists in that simple sentence.

In this situation, conflict is at issue. When conflict

occurs among people and a battle ensues, there is always

a winner and a loser, even if the status is relative.

There are always two (or three or four...) sides to every

story and the "victor" will pick the "version"

that is passed on to future generations. The victor will

be, of course, tempted by the desire to justify all of

his doubtful acts; thus, history with a distinct slant is

handed down as absolute fact.

Such instances permeate our modern-day

society to such an extent that we are barely aware of the

slanted point of view being presented to us.  Few people have the time to think

critically about everything that touches our senses. We

assume that CNN is adhering to the most important and

rudimentary rule of journalism: just present the facts

will minimal commentary. Tito and his supporters

commissioned Memorial Park, and the erected monuments

were carefully planned and considered. Which

emotions in particular did Tito want to evoke in his

public? How did he want them to remember

Kragujevac? Of course such devastating loss of life must

be lamented, but, Tito asks himself, is it possible to

lament and defend the Partisan image at the same time?

The monuments, inscriptions, and museum presentation all

lead the discriminating person to the following

conclusion: Tito decided to highlight the struggle at Few people have the time to think

critically about everything that touches our senses. We

assume that CNN is adhering to the most important and

rudimentary rule of journalism: just present the facts

will minimal commentary. Tito and his supporters

commissioned Memorial Park, and the erected monuments

were carefully planned and considered. Which

emotions in particular did Tito want to evoke in his

public? How did he want them to remember

Kragujevac? Of course such devastating loss of life must

be lamented, but, Tito asks himself, is it possible to

lament and defend the Partisan image at the same time?

The monuments, inscriptions, and museum presentation all

lead the discriminating person to the following

conclusion: Tito decided to highlight the struggle at  Kragujevac to remind the

public of the anger and noble intentions that motivated

the Partisans. Memorial Park was most certainly meant to

glorify and protect the Partisan image, even as it

simultaneously offered a forum for the understandable

grief felt by many visitors, testified to the barbarity

and danger the resistance movement faced, and promoted

historical awareness of the massacre. Memorial Park is a

tribute to the fallen innocent, but its alter-agenda is

to remind the public under whose banner so many

died: Tito's hindsight, as demonstrated by numerous

displays, quotes and arrangements throughout the park and

the museum, would have us believe that the victims at

Kragujevac were indeed innocent victims but they were

also victims under a Communist, or Partisan, banner. Of

course, this does not imply that all the victims were

Communists, but those who were Communists are certainly

showcased in the museum. The tragedy of the children is

also understandably prominent in Memorial Park; their

tragedy is beyond political affiliation, but it does

effectively demonstrate the depths of German hostility

and bestiality during World War Two and it reminds the

visiting public quietly that no matter the cost, the

Partisan Kragujevac to remind the

public of the anger and noble intentions that motivated

the Partisans. Memorial Park was most certainly meant to

glorify and protect the Partisan image, even as it

simultaneously offered a forum for the understandable

grief felt by many visitors, testified to the barbarity

and danger the resistance movement faced, and promoted

historical awareness of the massacre. Memorial Park is a

tribute to the fallen innocent, but its alter-agenda is

to remind the public under whose banner so many

died: Tito's hindsight, as demonstrated by numerous

displays, quotes and arrangements throughout the park and

the museum, would have us believe that the victims at

Kragujevac were indeed innocent victims but they were

also victims under a Communist, or Partisan, banner. Of

course, this does not imply that all the victims were

Communists, but those who were Communists are certainly

showcased in the museum. The tragedy of the children is

also understandably prominent in Memorial Park; their

tragedy is beyond political affiliation, but it does

effectively demonstrate the depths of German hostility

and bestiality during World War Two and it reminds the

visiting public quietly that no matter the cost, the

Partisan  activities were absolutely necessary to

halt the German war machine. activities were absolutely necessary to

halt the German war machine.

In essence, the post-war Communist

movement, directed by Tito, adopted the tragic memory

associated with the Kragujevac massacre, and while

preserving the integrity of the tribute, it orchestrated

a memorial that would claim some of the martyrdom of the

victims as its own. The same is true of many other

monuments that were erected under Tito's watchful eye. Is

it a malicious attempt to distort the truth of the matter?

It is meant to manipulate extensively public historical

consciousness? It is fostered by the desire to taint the

historical interpretation of a given event, here the

Kragujevac tragedy?

I assert that the Communists followed

a strict, subtle program regarding the interpretation of

the history of the entire Second World War, and Memorial

Park is an excellent example of this. It was a program

meant to protect their image, to complement and further

their power. Naturally, very few governments want to

undermine their own image, historical or contemporary.

The crucial points in determining the extent of the

affect of the government's program are the scale and the

severity of the manipulation. In post-World War Two

Yugoslavia, every possible step was taken by the

victorious Communists to stamp out controversy and

possible unflattering speculation about Partisan conduct

during the war. Due to the civil war and the conflict

with Croatia during the German occupation, such measures

were necessary to retain bratstvo and jedinstvo,

or brotherhood and unity. Kragujevac, as a popular site

for public events, offers the perfect stage for Partisan

revisionism.

Toward the end of the war, Tito was

still in the process of convincing the Allied powers to

relinquish their support of the royal government, which

had spent the war in England lobbying to insure their

return to power after the war. Prime Minister Churchill

and President Roosevelt were naturally suspicious of Tito

as a Communist. The balance of Allied power was

definitely in Tito's favor with the Allied decision to

support the Communists with supplies, but it was clear

that England would reevaluate the situation after the

conclusion of the war. At the urging of the English

government, the king agreed to a coalition with Tito in

July 1944. Essentially, the "coalition" was a

victory for Tito, as all of his demands were met and the

resolutions he had drawn up with other Communists

throughout the war were upheld. The relationship between

the two factions was redefined in a series of agreements

between Tito and Prime Minister Subasic, the Prime Minister of the royal

government. These negotiations extended into 1945, and

Tito, who pragmatically held no real interest in sharing

power with the king, astutely sidestepped any

responsibility to the royal government and managed to draw

up a government, with himself as Prime Minister, in which

the royalists had minimal representation. The culminating

point was reached when the Provisional Government of

Democratic Federal Yugoslavia was established on March 7,

1945.

In post-war Yugoslavia, it was not

only advisable for the Communists to keep a tight leash

on dissent regarding their wartime activities; it was

necessary for their political survival. Thus Tito had

sufficient motivation to pursue a subtle campaign of

"damage control" regarding Partisan wartime

activities, and it is a certain fact that Tito's

consolidation of power was anything but peaceful. On the

political front, Tito executed his enemies, sometimes

with little more than a show-trial, as in the case of his

archrival in the civil war,

Draza Mihailovic. On the public-relations front,

Tito demurely and almost indiscernibly manipulated public

opinion one public display at a time. Kragujevac had its

turn as the doors to Memorial Park opened. The process of

manipulation itself is a passive process, but the

political motivation behind it is definable and concrete.

Each monument, museum, and street sign was carefully

rationalized to glorify the Partisan efforts. A selection

of interpretations exists for any given historical event,

and one must be chosen for posterity. The Partisans chose

the most flattering. Millions of people visited

Kragujevac, a majority of them Yugoslavs, and the

impression with which they walked away was certainly

grief at the human tragedy, but it was grief filtered

through the protective, though very subtle, veil of

Titoism.

Thus, as time wore on, and objective

memories faded, the people of Serbia were constantly

reminded in subtle ways of the Partisan victory. The

value of the Partisan war effort would be repeatedly

emphasized so that the masses would be properly grateful

and docile. The Partisans won the war, they would be the

entity to celebrate victory and mourn the cost, dutifully,

at sites like Kragujevac. It is a strange mixture of defiance,

and defensiveness of that defiance, with pain and

a-political, human tragedy. The struggle against the

Germans cost lives

but in Partisan ideology, the end justifies the means.

The Chetniks would have had reason to commemorate

suffering and struggling, both of which they certainly

endured, but with their conservatism and caution in the

struggle against the Germans, I doubt Memorial Park would

have the same character if the Chetniks had won the civil

war. There would be a slant, simply a different one.

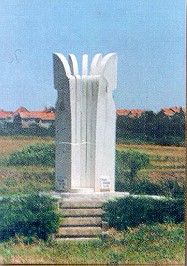

Monument of Pain and Defiance

is a graceful stone piece, with the unnatural and

anguished postures of the miserable. A serene and

peaceful flower garden is situated directly behind it.

The message is clear: "We, as Partisans, suffered

deeply, as did the victims of the Kragujevac massacre,

but our fight was not in vain, we were victorious and now

we have peace. Let us celebrate our victory, but never

let us forget our pain." Dutifully, there is

expression of pain, but the element of "advertisement"

is again present. There is no plaque or inscription, as

so many other pieces have. In its Spartan simplicity,

this statue speaks very loudly. The statue is, from an

apolitical point of view, an appropriate memorial to a

deeply disturbing and sad event, and if one looks a

little deeper into the presentation, it is also an

excellent example of party-line history.

|