© 2000 The American Long Ears Society

All Rights ReservedEquus Ferus Przewalski

BY ANY OTHER NAME ~

While domestic horses have been around for thousands of years, the Przewalski (or Mongolian Wild Horse) easily predates that by at least millions. Pronounced "sha-vahl-skee” and spelled a myraid of ways from Przewalskii/Przhevalsky to Prjevalski/Prschewalski, this ancient breed was first discovered and documented in 1881 by a Russian scientist/explorer named Nicolaii Alexander Przewalskii. On many of his outings he filled journal after journal of notes on the little asiatic wild horse that impressed him so. Native to Russia and Mongolia, these magnificent creatures were never really domesticated on a large scale, remaining wild and subject to hunting, starvation, and eventual extinction. Nicolaii realize this and after much thought, settled upon a livecapture program, sending specimens back to his native Russia to be studied and bred. At first, it was speculated that this breed was nothing more than a mule offspring between the Wild Ass x a feral horse. But Alexander insisted otherwise and they eventually were given true breed status, and aptly named “Przewalski,” by Zoologist friend J.S. Poliakov in 1881. Incidentally, the Mongol word for them is "Takhi,” and the Chinese word "Kurtag.”

Nicolai’s premonition eventually proved true as the Przewalski horse died out in the wilds by 1967 in SW Mongolia. The first Przewalskiis imported to the United States were a breeding pair to the Bronx Zoo in 1902. By 1977, an important and influential group formed called the Foundation for the Preservation & Protection of the Przewalski Horse, and through tremendous efforts, were able to reintroduce the breed back into the wilds by 1992. The infamous reserve, named the "Steppe Reserve Hustain Nuruu” in Mongolia is monitored closely by various protection groups and wildlife biologists. If it weren’t for the heroic efforts of breeding stations scattered over all over the world, the Przewalski (along with the Tarpan and Quagga) would have died out completely, severing an all important, irreplacable link with the past.

BREED STATS ~

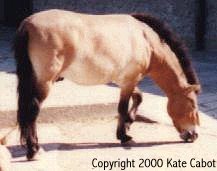

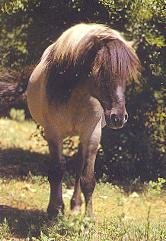

Przewalski’s comes in shades of sandy dun, ranging from yellow to golden to an almost reddish sandy bay. The mane is dark brown to black and stands up stiffly, like a brush, averaging 6 inches or more with the added unusual trait of having no forelock between the ears. The tail is long, brown to black, and shaggy, with the upper part covered with short lighter-colored hairs. The neck and chest are compact and solid, with virtually straight shoulders, no withers to speak of, and underdeveloped quarters on a ponyish 12-14 hands high frame. The head is straight or convex in profile, with massive bulging jaw muscles. The nose is beige grey, the color repeating itself around large brown eyes, throat, belly underside, and inside of legs. Black hairs rim the ears, inside and out, with a brown dorsal stripe running the length of their back and vanishing into the upper tail hairs. Sometimes, a shoulder stripe is visible. Legs are likewise black or rust colored up to the knee joint (with a slight feathering on the heels), above that on the forelegs are horizontal brown zebra stripes called “leg barring.” Their leg chestnuts are large and long, with ergots appearing on all legs.

Another unusual Przewalski trait is that it tends to molt or grow a brand new coat, mane, and new hairs on the upper part of its tail, twice a year (perhaps a residual trait tracing back to the harsh climates of central Asia). The only other “domestic” horse known to also do this, is the Curly Bashkir. The summer coat is sleek and shiny but by fall is replaced by longer, heavier, and warmer hairs. The final winter look with fur on its chest and a veritable beard on its chin (3-4 inches in length), likens the animal to a woolly bear caterpillar. By spring, the long hairs gradually fall out and a slow itchy shedding process begins.

Domestic horses don’t shed their mane/tail hairs annually like the Przewalski, but rather more like people, losing and replacing one hair at a time. Nor do domestic breeds fight like their Asian cousins, whose battles tend to be more frequent and more violent, often to the death. The Przewalski also has one extra vertebrae in the chest, hence an extra pair of ribs. Domestics have 64 chromosomes, compared to the Przewalski at 66, and the ass at 62.

The gestation period averages 11 months, just like that of the domestics, although many Przewalski mares have been known to foal late into their 20’s and 30’s. Newborns are long-legged and wobbly with a light colored coat and tufts of curly hair along the neck. The coat eventually darkens, and by 6 months of age, a true mane will grow in its place. Given the opportunity, foals will stay alongside their Dams for 2 years, but are usually driven off by the stallion (if a colt) or stolen by another herd stallion (in the case of fillies).

OTHER PRIMITIVE HORSES ~

After the ice age, two distinct types of horses emerged and survived through to modern times. One was the Przewalski of Asia, the other the Tarpan, a wild horse of the southern Russian grasslands. Not much bigger than a pony, the Tarpan was lighter built, and less chunky than the Przewalski. Discovered & documented by S.G. Gmelin in 1768, this ancient breed was once speculated to be a hybrid cross between the Przewalski and a Mongolian Pony. Born a peculiar blond-brownish coat color that darkens to mouse-dun after a few months, they too sported dorsal stripes, thick semi-upright manes, with little to no forelocks. Like their cousins, Tarpans were hunted and starved to the brink of extinction. The last known wild Tarpan reportedly died at a village in the Ukraine in 1880. Two attempts to “breed back” the Tarpan were made, the first beginning in Germany before World War II, using Przewalski horses and later in Poland using local Konik ponies. Examples of the Tarpan currently exist, though in “recreated” form (that is, bred up from individuals who resembled ancient stock), much like the case with Quaggas from the Quagga Project.

Perhaps one of the most intriguing finds of primitive breed discoveries this century has been that of the Riwoche (pronounced “ree-woe-chay”), a 4 foot high wild horse ancestor, discovered in 1996 along an isolated 17 mile stretch of valley in the Riwoche region of Tibet. A team of French, British, and Spanish explorers happened upon a herd accidentally and described them as having a beige coat, bristly mane, black dorsal stripe, lower black legs complete with leg barring, and a triangular wedge shaped head resembling the Przewalski. Current speculation is that this is a relic population, isolated from influences of any other breeds by high wall passes of 16,000 feet, thus preserving it’s unique characteristics for centuries. Also living in the same valley are the Bon-Po people, natives to the region whose farmers frequently catch & release the horses when riding or packing services are needed. Because this arrangement, the explorers were able to get within 15 feet of the free-roaming horses without their spooking and running off.

INFORMATION ~

For more information on any of these primitive breeds, we suggest contacting one of the following groups below:Foundation for the Preservation & Protection of the Przewalski

Mathenesserstraat 101a.

3027 PD Rotterdam

Netherlands

The Wild Equid Society

c/o Judith Kolbas

Flat 19 - 119 Haverstock Hill

London NW3-4RS

England

Some fabulous Przewalski thumbnail pix here!

How about spending your next vacation out among wild Przewalski in Mongolia? Visit this website to learn more about this wonderful opportunity!

Przewalski Postscript ~ another fabulous website on Prezzie's with if you're in the market for more good reading!

(This Page last updated: November 30, 2000)