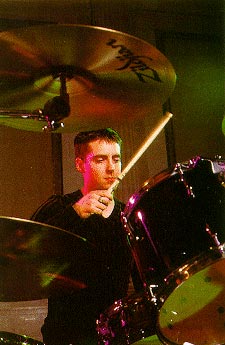

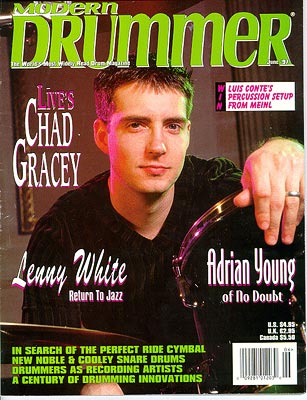

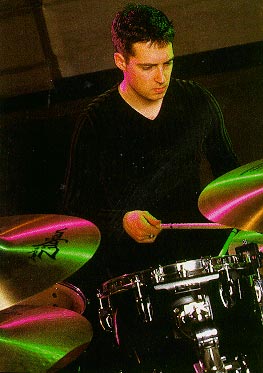

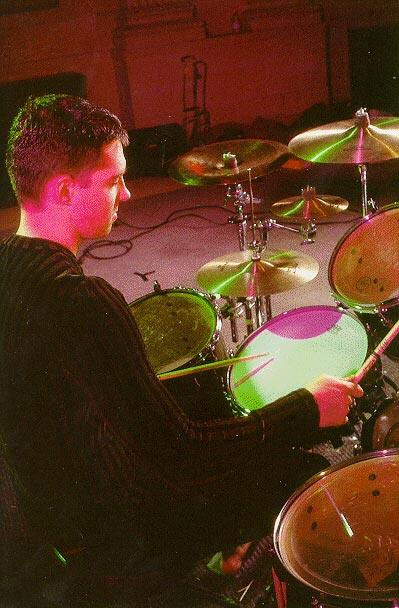

Live's Chad Gracey: To The Point

Chad Gracey Plays in a band that has sold more than seven million records, performed hundreds of shows, graced the covers of Spin and Rolling Stone, performed at Woodstock II, put together one of the most impassioned sets of music in the MTV "Unplugged" series, and been hailed by fans (and, lately, by critics) as modern rock's savior.

Still, Gracey doesn't seem entirely comfortable with the fact that, of all the things he might do in life, he's a drummer.

"It's weird, in a way, because I've never really cared about being a drummer," Gracey admits. "Drumming was just something I got into when I was young, and I think I would have given it up a long time ago if things hadn't worked out the way they did."

Strange sentiments, coming from someone who has been praised by Neil Peart and other "name" players as one of their favorite young drummers. The compliments are easy to understand, though, once you dig into the music Chad makes with his band, Live.

Gracey's unconventional rhythms, addictive grooves, and implacable knack for emotional impact are the unsung chemicals in the band's artistic formula. Few modern rock drummersuse the toms and cymbals more musically, and Gracey's ghost notes and efficient strokes belie his complete disinterest for any formal practice or training. For all that, Gracey simply shrugs and chalks it up to his ear.

"I know what I want to hear, and I guess I'm able to play whatever I hear in my head," he says. "I'm sure lessons could help me be a better player in some ways, but I'm more interested in being a good musician for this band than in being a good drummer. As long as I'm happy with what I'm playing and the guys are happy with it too, that's fine with me."

Gracey's priorities haven't changed since the seeds of Live were first planted a decade ago in York, a small blue-collar town in southern Pennsylvania, where Gracey and his bandmates attended the same junior high and first played together under the name Public Affection. Even then, they wrote songs resonating with spiritual and political overtones, inspired in part by singer Ed Kowalcyk's studies of Henry Miller and philosopher Jiddu Krishnamurti.

For his part, Gracey saw it as little more than something fun to do after school and on weekends with his best friends. Their first tunes reeked of U2 and Midnight Oil, but it mattered little to fans hooked on the band's youthful charm. Gracey and his bandmates decided to forego college, changed their name to Live, and released the tantalizing Mental Jewelry before they were out of their teens. Through it all, Gracey simply didn't have time to think about the commitment he was making to music.

Now twenty-five, he has since married and moved to Portland, Oregon, where he joins the frequent-flier club for his treks toward Pennsylvania for band rehearsals. For all his supposed apathy for drumming, Gracey will see nothing but sticks, skins, shells, and rims for the next two years, as Live tours in support of its haunting third album, Secret Samadhi.

Some will undoubtedly see the disc as a backward step. The sing-along anthems that sent 1994's Throwing Copper to platinum six times over are scarce on the new album. Though it's also Live's most rhythmically modest effort to date, Gracey latched onto an unprecedented emphasis on mood and atmosphere to steer his performance into new directions. If nothing else, he says, Secret Samadhi marks the band's greatest artistic leap.

"If we'd wanted to we could have written songs that sounded just like 'I Alone' or 'Lightning Crashes,' but I don't think we had it in us to make this kind of record before," he says. "There's a lot of depth here. These may or may not be the kind of songs people will love on the first listen. But if they really sit down and let the music sink in, we think that's when it will really grab them."

MP: A lot has happened for you in the past couple of years. You got married, moved to Portland, built a house. Were you anxious to get back into the band thing, or was it hard pulling yourself out of Oregon?

CG: Well, let me put it this way: It was a good, long break for me and I enjoyed every minute of it. I was totally burned out after the last tour. All the travel and something like two hundred fifty shows--it was non-stop. I'm the kind of person who really enjoys the quiet times. I'm sort of a homebody, I suppose, and I just spent a lot of time after we got off the road working on my house and hanging out with my wife. It's a lot different vibe in Portland than it is in Pennsylvania--a lot more laid-back and beautiful--and I had no trouble at all adjusting to that.

MP: Were you completely away from music in the time between the last tour and the sessions for the new album?

CG: I didn't play at all. I don't even have a set of drums at my house. I figure we get together enough as a band that I play as much as I need to, and I've never been someone who likes practicing drums on my own. In fact, I can't stand playing by myself--I just won't do it. My whole life as a drummer has been spent in this band. That's the only way I know how to play and the only way I want to play--with these guys. But I felt more prepared for this record than for the last one. I think we all felt that way.

At one point, when we were touring for Mental Jewelry, we stopped writing on the road, and that really put some pressure on us afterward because we didn't have any songs ready when we came off the road. That left us in limbo for the next few months until we actually got into the writing groove for the songs that ended up on Throwing Copper. We were fine once we got going, but we were really sweatin' it there for a while. We didn't want to be in that position this time around, so we really trained ourselves to write on the road during the last tour. We'd play a couple of songs at soundcheck, maybe work on some new things for a half-hour or so. And we were on the road for so long that we had a lot of songs and ideas for songs after we came back from our break.

We got off the road in late September of 1995, and we got back together in November, demoed a bunch of songs that we'd written on the road, and then took a couple of months off before going off to Jamaica to write some more. We ended up writing three songs down there--"Unsheathed," "Ghost," and "Gas Hed Goes West"--and we started recording at the Hit Factory in New York City in May.

MP: Those are pretty diverse environments--from the road to Jamaica to New York. Do you think there's a distinct difference between the songs you wrote on the road and the ones you wrote on the beach?

CG: Maybe on some subconscious level it made a difference, but I don't think it's anything you can hear on the record. A guy at our label, Radioactive, came up with the idea of sending us to Jamaica. I guess his thinking was we could just hang out, relax, enjoy the sun--and we're not fools, you know. We figured, "Sure, why not?"

We definitely had a good time there, but I don't know if there's anything that came out of Jamaica that we wouldn't have come up with in any other place at that time. You'd probably have to ask Ed or Chad [Taylor, guitarist] about that, because they write all the songs. I'm pretty sure it didn't affect my drum parts.

MP: You mentioned that you were not playing while away from the band. How did you get yourself into playing shape for the record?

CG: I've never really had a problem with that. I can take off for months and months and still be able to play as well, I think, as I did before. It's kind of like riding a bicycle for me. Now, for touring, it takes some time to build up the endurance you need. But if there's any rustiness at all, it's just in remembering some of the older songs we haven't played in a while.

MP: But some of the parts you come up with are pretty creative and deceptively elaborate, particularly how you weave the toms and cymbals into the basic beat. After a long absence, don't you ever trip over yourself when you're first picking up the sticks?

CG: Not really. A lot of what I play might sound more complicated than it really is. For me, something like hitting the tom at a certain point in the beat might just be taking my right hand and, instead of hitting the ride cymbal, hitting a drum. Then on the next stroke, instead of hitting the snare with my left hand, I might hit the hi-hat. It's really just a right-left-right-left sort of thing, and trying different things with that. My bass drum parts are usually pretty simple, and I don't do a lot of fast double hits or strokes with one hand.

MP: When you were writing on the road, did you spend much time thinking about or working out your drum parts?

CG: It depended on the song. Some things come together for us very naturally. I'll hear something that Chad is trying to do and something will immediately come into my head. I usually get an impression pretty quickly of what I want to do, but sometimes I have to tinker with a song for a while until the part sounds right.

Sometimes it's not so much a part I have to work out, but some of the accents and crashes. I like to throw snare strokes into some weird places because I think they help to bring out a verse or chorus and keep the rhythm flowing. But I have to make sure I'm not doing something that gets in the way of what Ed or Chad--or even Pat [Dahlheimer, bass]--is doing.

In the song "T.B.D." [from Throwing Copper], we start off really softly, but there's still a lot going on in the rhythm. I think Pat and I are probably playing more early on, during the quiet parts, than when the song really gets moving. When you're playing that softly, every note you play or don't play really affects the music, but the notes I put in there aren't getting in the way of Pat's bass line. And once the volume builds up and we're all laying into it towards the end, I'm not playing as many notes. I'm just trying to really kick the song.

MP: A lot of drummers today recognize you for the unique rhythms you come up with. For instance, what made you use the maraca in your ride hand for "Pain Lies On The Riverside"[from Mental Jewelry]?

CG: Chad had these crazy African maracas with old, beat-up, rusted bottle caps in them. I was just trying something different, so I picked one of them and started using it in the song. I didn't give any real thought to it. I'd never heard that done before. It was just a sudden inspiration and it clicked.

I think if I would have let it freak me out that I was using a maraca instead of a stick hitting a cymbal, I'm not sure I could have played it so easily. Maybe if I would have tried something like that for the first time now, it would be more difficult because I'd be more set in my ways. But I was just a kid then. I hadn't been playing drums all that long, and I didn't know any better.

MP: Have you taken more of a role in the songwriting these days? Or do you even want to get involved in that at all?

CG: No, not really. I'm a little up front these days lately about arrangement and maybe how a song will develop dynamically, but the initial ideas still come from Chad and Ed. I don't play guitar, you know, and I really don't have any aspirations to write music from scratch. It's just not what I do. I'm really content to jus kick back and be the drummer.

MP: Your playing on Secret Samadhi seems much more straight-ahead than what we've heard from you before.

CG: Yeah, I'm playing a lot less. I don't know whether you'd call that maturing or not, but I think experience has something to do with it. Mental Jewelry was very much driven by bass drums, whereas we really brought out the guitar parts for Throwing Copper. I think with the new record, it's not just about writing good songs, but sort of creating an atmosphere to go along with them.

A lot of that comes from just playing to what was there and trying not to overdo things. Not that I think I overplayed on the other records or anything like that, but most of the songs on the new record are more mellow than the songs on Throwing Copper. The tempos are more similar and they all seemed to call for more groove. Once I heard what was going on in the music, I just had to switch gears and lay in the pocket. I may not be doing as much on the toms as I did before, but I made the parts interesting in my own little way.

"Ghost" is an example of a song that threw me for a while. The drum part in the verse came to me right away, but I had to really think about the chorus, which seems kind of funny because it's really just a straight-ahead rhythm. At first, I was playing around in my head with a lot of different ideas, and I tried different things that might have sounded good on their own, but they were way off for this song.

"Ghost" was one of the songs we wrote at soundcheck, so I took the tape home and listened to it, and as soon as I settled into this real basic beat, it sounded good and I knew that's what I needed for this song. And as it turns out, most of the songs on this record called for that kind of approach. It wasn't anything I told myself I had to do. It just worked out that way.

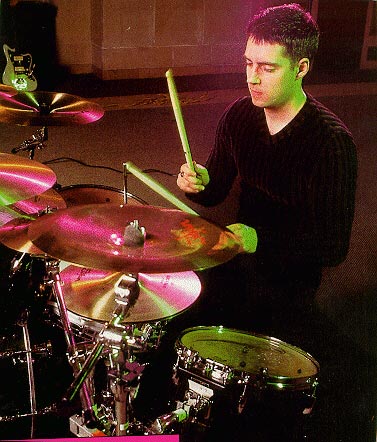

MP: Have you changed your setup much since the last record or tour?

CG: Not really, except that I've gone to bigger cymbals now. All my cymbals are basically one inch bigger in diameter than they were before, just so I could get a heavier sound in the studio, which is something I felt I needed for the new songs. I didn't necessarily want louder sounds, just maybe darker sounds.

I'm also going with coated Remo Ambassador heads now. I used to play the Attack double-ply heads, which worked really well for Throwing Copper and when we were on the road. But in the studio this time around, I wanted something more mellow and ambient, almost like a traditional jazz sound. I don't know if that comes through on the recording, but I could hear it when I played, and it probably affected my parts a little because I was hearing things differently.

MP: Why did the band decide to co-produce the new album as opposed to leaving it in the hands of an outside producer, as you had in the past?

GC: It had a lot to do with the fact that we didn't want to work with Jerry Harrison again. Don't get me wrong--we love Jerry--but we just wanted to change things up and see how that would affect our music. Jay Healy, who co-produced with us this time, is a friend of ours who worked with us six or seven years ago on a demo we did for Giant Records. We had sort of a family-type relationship with him, and we knew he was a good engineer.

We didn't go into this album wanting or knowing we were going to produce ourselves. Jay was helping us during pre-production and making a few suggestions here and there. But once we got into the studio, he became the engineer and was completely consumed with that job. So we just had to take the reins and not have anyone hold our hands anymore.

We're the kind of band that can lose its direction pretty quickly as far as work goes. We're not necessarily the most disciplined band. I mean, when the four of us get together, we might not feel any vibe going in rehearsal or in the studio, so we'll just decide to go do something else together instead of kicking ourselves in the butt. When we were actually recording, maybe one of us would come in at 1:00 and someone else would wander in at 1:30, and we'd just relax awhile. Once we got to our instruments and started playing, we'd get down to business. But sometimes it would take a while for that to happen.

In the end, I think it all worked out fine for this record, and what we got turned out great. But for the next record, I don't know. We might even have Jerry come back in or maybe someone else, just to have someone to say, "You be here at this specific time," because I think we work better that way.

MP: By not having a producer to guide you, did you take more ownership of your drum sound this time around than ever before?

CG: I left most of that up to the engineer, though I really took more of a role with my snare sound. I used a lot more snare drums than I had before. Most of them were piccolos--I've always been a big piccolo fan--but this time I played a greater variety. I played wood piccolos, brass piccolos--some that were deeper-pitched or maybe smaller in diameter.

I've been into piccolo snares since before we recorded Mental Jewelry. You get a lot more out of the drum at lower volumes, but you also get the kind of crack you can't get with bigger drums. And you'd be surprised at how diverse the sound can get just by using different piccolos, maybe even more so than with standard-size snares, because it's such an immediate punch. My Pearl brass piccolo is my mainstay, but I probably ended up using four different snares on the record.

MP: You talked a little before about how you physically play your parts, by hitting different drums or cymbals while keeping the right-left-right-left pattern in your fills. How did you develop that particular approach?

CG: Pretty much from when I just started out playing, when I was about fifteen. I bought a drumset a month or two before I joined the band, and the first thing I remember playing to was a Beatles record--just because it seemed easy to play. From there, I'd play to Tony Thompson with the Power Station and to some Chili Peppers records. I've never really thought much about my style; I guess it just seemed like a natural and easy way to play.

Not that I'm lazy or anything, but when it comes to drums, I've never had any desire to work on anything just so I could play some crazy fill. That's just not me. Like I said, if it wasn't for this band, I don't think I would have kept playing the drums at all. But on the other side of it, I also don't ever want to feel like I can't do something in a song because I'm not able to play it. So I suppose if I thought of something that would work well in a song and I couldn't play it, I'd work on it a little to see if I could make it happen.

MP: How long ago did you realize that playing the drums wasn't all that important to you?

CG: Probably when I was in about ninth or tenth grade, around '86 or '87. Back then, I was into playing music, but only because it was with these guys, not because I felt so driven to play drums. And I knew that right away because I couldn't stand playing by myself. I've never been into practicing alone just to get better. I've never wanted to sit and learn every Neil Peart part. I've always wanted to come up with my own parts, and it's always been about the music we make in this band.

MP: Though you say you never really tried to pattern yourself after other drummers early on, have any drummers influenced or inspired your style in the past few years?

CG: Yeah, probably more in the past couple of years than at any other time. I really like the way Eric Kretz plays with Stone Temple Pilots, not so much the things he plays, but what his parts do for the music. Matt Cameron's another guy I'm really into. He has a real distinct style, but everything he plays enhances the music.

I've never been into drummers who can play a million miles an hour and do all those gymnastics. I think that's kind of boring, actually, and it's not really fun to listen to. eric and Matt just hang back and do some cool, tasteful stuff. I try to keep that kind of philosophy in mind when I'm coming up with my own parts, but I think that comes sort of naturally to me, too. I'm a pretty laid-back person and I really don't like the spotlight. I don't care if people even notice my drum parts, as long as they like the music.

MP: What did your parents think about you guys, at such an early age, deciding to pursue the band full time?

CG: When we first started, I kind of had other ideas about what I was going to do in life. I really had an interest in going into the medical field someday, maybe becoming a doctor. I still have an interest in that, actually, but I've never looked back and thought, "Gee, maybe I should have done that instead." My parents have been supportive of me all the way. All our parents have been. They could see we were pretty serious about the music and pretty confident we could go somewhere with it, especially during our senior year of high school, when we made the commitment to hold off on college and see where we could take things.

I was never nervous about doing that because I wasn't alone. I had three other guys determined to take the jump with me. We just decided we were going to do this, no matter what happened, and we were going to make it no matter what happened. I don't know if it was just young, dumb enthusiasm or what, but even back then, we were really confident in ourselves. I do marvel now at how big we've become, but I can't say we didn't expect or hope for it. People think we're this overnight success, but a lot of them don't know we've been a band for eleven years, so it seems very gradual to us.

MP: When the band's popularity really began to skyrocket in 1995, did that catch you off guard or did you enjoy it?

CG: I thought it was incredible, really, and it was a fun time for us. The whole year was a real progression--we started in the clubs, then we got excited about moving up to theaters, then we got to move into 30,000-seaters. It was just this amazing climb, and it was funny because our booking agent predicted that we'd be doing amphitheaters by the summer of '95. We thought he was out of his mind. Since then, we've come to find out that we really like playing the bigger places.

The acoustic sets are fun, too, and the "Unplugged" thing worked out well for us and maybe gave fans a more intimate look at us. From the outset, though, We've always seen ourselves as a band that could play those kind of places--not necessarily an arena band, but a larger-venue band. We don't tailor the music to that, but we definitely have it in mind once we've written a song. We have a good idea what will go over well in the bigger places and what won't. Larger stages also open us up to doing creative things with lighting and video. We're opening the new tour in theaters, just to get our feet wet, but then we're going right into the amphitheaters and big arenas.

MP: Looking back to your first recording sessions, how did you react, personally, to the pressures of working in a studio?

CG: I actually liked it, especially for songs where I'd already had the drum parts down in my mind from rehearsing them. The only times I really got uptight about anything where when Jerry Harrison would make some suggestions for arrangements that conflicted with a part I'd already come up with. His ideas were great, but I didn't want to change my part. It just took time for me not to take those things personally.

MP: When you're recording now, are you playing along with the whole band or just to a rhythm track?

CG: Everything that's on tape pretty much came from "the" take. It may not have come in one or two takes, but we played all our parts at the same time and kept the best take from the four or five that we might cut for a song. Ed overdubbed most of his vocals and his guitar parts, but we kept everything else.

We've always recorded like that, and I think that just comes from playing together live all the time. We're just so used to playing that way that it's natural for us to carry that over into the studio, and I think the energy and spontaneity of that really comes through in the music.

MP: It's probably starting to get difficult for you now to put together a set list without leaving somebody's favorites out of the mix.

CG: Well, we obviously want to promote the new record and play it as much as we can. We've put together a sevety-five-minute set that has all the new songs except one. We've got three songs from Throwing Copper and one from Mental Jewelry. At this point, we figure we've pretty much played everything off the first record that needs to be played, and we're ready to move on to new stuff. I hope our fans are, too.

MP: Do you ever see yourself getting involved with any outside projects?

CG: The only outside projects I see doing have nothing to do with music. I'm really into carpentry. My father's a carpenter, and I like building stuff and fixing things around the house. I just remodeled one of the rooms in my house, which I'm pretty proud of. But as far as music goes, this band is the only thing I want to do. I've never played drums without these guys and I probably never will.

I'm married now, I have a house, and music will never be the most important thing in my life. I'm not saying I don't enjoy what we do. I enjoy it very much--we all do--and we plan to be making music together for a long, long time. In some ways, I think we are just now touching on some of our most creative ideas, and it would be a shame to cut that potential short. But if it ended tomorrow, I wouldn't be too upset about it. We'd all still be great friends, and I'd just go home to my quiet life, be with my wife, and blend into the scenery.