Those of us who regard Family as one of the most consistently fine hours on television are loath to peer into the program's clockworks to see what makes it go. We might find the illusion shattered. What if the Lawrences of Pasadena, so palpably real on the tube each week, and so decent, turned out to be -- unmasked -- just another troupe of bored and cynical actors, cleverly putting us on at show time?

Blessedly, this is not so. It's been close to five years since the Lawrences were created. But on ABC, they're only in their second full season. The story of how they got there is too full of snags, happenstances and 11th-hour rescues to be believable as a script for the series. As a result, gratitude and concern are bywords among the Family family, off camera as well as on.

In its struggle to make the ABC schedule, the show had three strikes against it. The network found the Lawrences, at various critical times, (1) too well-educated and too well-dressed, (2) too true-to-life for Family Viewing Time and (3) simply "too good for television." During the same period the network found three other shows out of the same shop -- Spelling-Goldberg Productions -- irresistible: S.W.A.T., Starsky & Hutch and Charlie's Angels.

The Lawrence Saga begins in the summer of 1973. The two production partners meet for dinner to kick around new-show ideas. Aaron Spelling: skinny, pipe-smoking, Texan, 50ish, onetime actor, longtime writer. Leonard Goldberg: not yet 40, handsome, muscular, up from Madison Avenue and network executive suites. Goldberg has been following the cinéma-vérité adventures of the Loud family on public television with fascination. "I'd love to see a contemporary traditional family get time on TV," he says. "I just don't buy this premise that the American family is disintegrating."

Spelling agrees. Good idea. Worth investing in a pilot script. Calls for a script by some writer from outside television, who knows how to construct solid drama without resorting to shoot-'em-ups and car chases. They narrow the field to one such writer: Jay Presson Allen, a woman whose novels and screenplays they both admire.

Two Weeks Later, Summer of '73. Lunch with Jay Presson Allen at a Beverly Hills restaurant. Miss Allen says yes. Turns out she is an avid television fan who has never written for the medium because nobody has ever asked her to, until now.

Fall of '73. Allen turns in script, "The Best Years." The Lawrences -- parents Kate and Doug, son Willie, daughters Nancy and Buddy -- are born. Composite of two families Miss Allen knows -- one from Texas, the other from Philadelphia. Story, centering on Nancy's husband's infidelity, is set in suburb of Philadelphia.

Script submitted to ABC. Verdict: dynamite! So dynamitic the network is stunned into silence, and the expected order to film a pilot episode is not issued. Spelling and Goldberg find out that the programming people have decided to go with another project, "The Chadwick Family," starring Fred MacMurray. The Chadwicks were more "typical" and therefore more "lovable" than the Lawrences because they didn't play tennis, or dress so conservatively, or talk like adults about such recondite things as how little girls change anatomically at puberty.

Fall of '74. Michael Eisner, old compadre of Len Goldberg's, takes over ABC's prime-time series programming. Goldberg nudges him about "Best Years." Eisner rereads it, still thinks it's dynamite. Will put it in briefcase to take on upcoming trip to New York headquarters. On New York agenda is the Mike Nichols Question.

Nichols, ex-comedy-improv partner of Elaine May, director of "The Graduate" and "Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf?," is under open-end ABC contract for his TV debut as producer, but is without a first project. Nichols says, "I have come across one thing that appeals to me very much. A script by my friend Jay Presson Allen." Eisner recognizes cue to pull script from briefcase. Just happened to have a copy. Cloutwise, it's Nichols all the way. ABC orders pilot of "The Best Years."

January '75. Co-production deal set up between Spelling-Goldberg and executive producer Mike Nichols. Name of series changed to Family because "The Best Years" is too close to Samuel Goldwyn's "The Best Years of Our Lives."

February '76. Nichols, told that year-round outdoor shooting is not possible in the Philadelphia area, says: "We'll have to move the family to California." Agreed that the Lawrences must live on a real street in a real city, not behind an Andy Hardy picket fence on a studio lot. Nichols rents a car, goes scouting. He reports back that South Pasadena is Philadelphia Main Line West. House on Milan Avenue "borrowed" for pilot location.

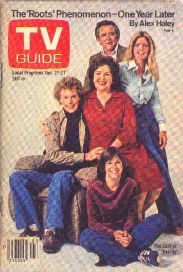

Nichols re-certifies his genius in casting Family with a finely balanced cadre of actors: Sada Thompson, James Broderick, Gary Frank, Kristy McNichol.

March '75. Family pilot screened for 15 ABC executives. Goldberg: "They started calling us immediately. Most beautiful pilot they'd ever seen! They came out with tears in their eyes! Aaron and Mike and Jay and I and all the cast were absolutely euphoric."

April '75. ABC announces its 1975-76 season line-up. Family is not on it. The reason is leaked: "The show is too nice to be set up against all those high-powered contenders. It would just get eaten up. But we still love it and it will be seen." Goldberg: "How? Are we supposed to take a projector and go door-to-door and show it to the people?"

Summer of 1975. Fred Silverman named savior-designate of foundering ABC network. He screens inventory of pilots. Instantly hooked on Family. "Just may be the most beautiful pilot I've ever seen. You have my word that this series will go on the air in midseason. Get a staff. Order scripts..."

September '75. Spelling-Goldberg hires Nigel and Carol Evan McKeand as line producer and story editor. McKeands old hands at scripting and editing (most recently on The Waltons), although new to marriage. Bank of scripts ready for January air time.

Nov. 26, 1975. ABC announces its midseason schedule. Family is not on it.

Thanksgiving Weekend, 1975. All principals stunned. Leonard Goldberg at La Costa sports spa for holiday. Aaron Spelling at home with family in Beverly Hills. McKeands in Hollywood Hills, with visions of sugarplums (back to The Waltons?) deadening their heads. Sada Thompson reading stage-play scripts, searching for a role. James Broderick packing to fly to his dream-house in Ireland.

Spelling and Goldberg get on the phone, Beverly Hills to La Costa. They will not give up. They roust Fred Silverman out of his Thanksgiving rites back East. What the hell happened? Silverman contrite but unconciliatory. It is his job, he says, to turn the network around. He has no choice but to go for "big numbers" with "firepower shows" like Laverne & Shirley, Bionic Woman, Donny & Marie. Later they will afford a luxury like Family.

Spelling and Goldberg still do not give up. They get a fourth party on the line, Silverman's boss Fred Pierce, in New York. The marathon conference call goes on, pleading and placating, demanding and denying, through the weekend. Turkeys go uncarved, pumpkin pies unpunctured. Leonard Goldberg, huddled over the phone in his La Costa kitchenette, finally hangs up. It is 1 A.M. Sunday morning, 4 A.M. back East. Fred Silverman has just said, "I think I can work something out."

Monday, Dec. 1, 1975. Carol and Nigel McKeand have backed their station wagon up to the Family office-bungalow on the 20th Century-Fox lot, doing what dismissed writers traditionally do: loading up on supplies -- paper, paper clips, staples, pencils, manila envelopes.

There is a call from Goldberg. "Take the covers off your typewriters," he says. "We're in business." Silverman had struck a compromise. In March, after the winter-season wars had quieted down, ABC would air six consecutive episodes of Family.

Spelling-Goldberg's contractual holds on the cast had expired, but all the actors leaped at the chance to bring the Lawrences to network life.

March 9, 1976. Family went on the air with the merest dribbling of pre-show publicity. It recorded an astonishing 40 share in the ratings.

The fall of '76. Family became an ABC fixture. The Lawrences of Pasadena, who "lived too well," "dressed too well" and "spoke too well" (about things like death, divorce, alcoholism, homosexuality, and the simple pains of growing up and of being parents), knocked hyped-up competitors like Switch and Police Woman out of the Tuesday 10 P.M. box.

January '77. It remained for CBS to give Family its biggest -- if back-handed -- accolade, by bringing up a howitzer like Kojak to blast at it from across the video trenches. Family returned fire with a candid, tender story about Willie's affair with an older woman. It left Lieutenant Kojak in the starting gate, choking on his lollipop.

So that's how it's done in Video Wonderland. Easy as falling off a program log. Nothing to it. Hah.

Mike Nichols, having executed what executive producers traditionally execute -- the launching of the show -- now enjoys the emeritus rank of Family's First Fan. Jay Presson Allen continues in the role of creative godmother, but not on a nuts-and-bolts, script-by-script basis. What comes through on the air is an affirmation of Leonard Goldberg's original hunch: that the death knell of the traditional American family is not yet ready to be rung.