Small Boat, Large Ocean

by K.P. Chin

Small Boat, Large Ocean

by K.P. Chin

When it became apparent that I was not going to be ready for the June 15th start of the 1980 Solo TransPac Race from San Francisco to Kauai, Hawaii, I decided to officially withdrew from the race. But go I must, for it was a personal odyssey for which the first step had been taken long ago.

My goal was to sail alone across an ocean. Could I do it?

I did not know exactly when the idea first occurred to me, but it had been bubbling in my head for many years. I suppose it did not come as an instantaneous inspiration, but began more like a seed in the fertile imagination of a young mind that grew and grew until it had become an all consuming passion. Ever since I was a young boy growing up in Malaysia and encouraged by my Outward Bound School experience I have always wanted to sail solo. Now that I am in the United States I decided to seize the opportunity.

For the trip I got a used Cal 20, one of the early Bill Lapworth designs, which I strengthened and modified for easier offshore singlehanding. Having raced on Cal 20s regularly on San Francisco Bay, I found them to be small but able and seaworthy boats. And besides, it was all I could afford at the time. With a real boat on which to base my dream I went to work achieving it with a will, working days to earn money, and nights and weekends on Chalupa. Whenever my willpower faltered, I reminded myself of a passage from Richard MacCullough's book "Viking's Wake":

....and the bright horizon calls! Many a thing will keep till the world's work is done, and youth is only a memory. When the old enchanter came to my door laden with dreams, I reached out with both hands. For I knew he would not be lured with the gold that I might later offer, when age had come upon me.

The night before I left I hardly slept. My mind was alive with a thousand questions. Was I ready? Yes. Was Chalupa adequately prepared? I'd done the best I could. I learned that one can never be 100 % ready in a venture like this, for too much analysis might lead to paralysis. I just took care of the major stuff on my to-do list and did the best I could with what I got. Before long it was dawn. I had my last hot shower for many a days to come. After a small breakfast I was driven by friends to Gas House Cove where Chalupa was waiting. There was that familiar summer fog over San Francisco Bay and a light breeze blowing that morning as I raised the sails and said good-bye to my friends who had come to see me off.

Riding the early morning ebb tide on June 18, I tacked my way out of San Francisco Bay under the Golden Gate Bridge. Many times before I had sailed under that bridge and each time I wondered what it would be like when I finally set out on my own. Now it stood shrouded in fog, keeping a silent vigil. With one last glance at the city, I was finally on my way to cash in on the long awaited dream that had kept me going these last few years. The course was set and there was no turning back. My throat was dry and a bit constricted but I felt confident and excited.

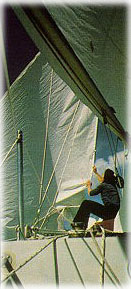

Changing

head sails.

Changing

head sails.

Week one was typical of Northern California weather. The first two days were cold and foggy, sometimes with winds from 25 to 30 knots. Chalupa was making good speed. In one 24-hour period we made 131 miles on the log and I was both amazed and elated. While Chalupa seem to come alive and relish the sail, I was seasick, cold, wet and exhilarated, all at the same time. Since we were heading down the coast in the shipping lane at this point, I could not afford the usual eight hour stretch of sleep. I took only hourly naps between my look-outs, piloting and sailing the boat.

Keeping food down was almost impossible at first and I allowed myself only water and crackers. Late in the second day we took a wave through the companionway hatch and I ended up with about two inches of sloshing seawater on the cabin sole. Another lesson learned. Keep the hatch board closed at all times in windy conditions on a small boat.

Adjusting

the wind vane.

Adjusting

the wind vane.

On the third and fourth days out I managed to dry out most of the soaked gear, clothing and canned foods as the sun made a much welcome showing. Then we had three days of flat calm, which was most frustrating. The constant rolling and flapping of sails was beginning to wear on my nerves. I could not even keep my cruising spinnaker filled.

My best day's run during this period was a depressing 20 miles in 24 hours. One night I was awakened by the slatting of the main sails to find the sea a flat mirror in I could see my own reflection on the water by moonlight. It was rather eerie. I decided to just furl the sails and went back to sleep. At sea one have to rest whenever there is an opportunity. The next day we picked up a breeze and it was smooth sailing at last.

After the first week, the reality of being alone occurred to me. That first week I was too busy with adjusting to life at sea and the constant motion of a small boat. I had never been totally alone and so far from civilization for so many days in my life. My world consisted of the clear blue sky, Chalupa cutting a wake through the deep blue Pacific under us and what I could see all the way to the horizon which was about three nautical miles all around. The need for company, however, was surprisingly absent, I was actually quite content, happy and enjoying the sail. I was glad that the tensions and anxieties of preparing for the voyage were behind me, and that I had settled down to my simple daily existence at sea: cooking, sleeping, sailing, navigating, reading, and enjoying the peace that comes with venturing out to sea alone. I was also learning to deal with the inevitable minor emergencies that occurred. A ripped sail here, a chaffed line there and so forth. When soloing, your, accomplishments, joys and failures are all intimately yours. Therein I think lies the irresistible appeal and challenge which possesses some of us who sail singlehanded. Someone once said, "if you are lonely when alone then you are with bad company." I could not have asked for better company at the time.

Before the trip I was asked how I was going to cope being alone at sea. Being a, recreational jogger, I sometimes interchange my jogging and sailing experiences. For example, if I were to run 12 miles and looked at it as 12 miles, then it would feel like a very long distance. But if I were to break it up into three groups of 4 miles each for example then it would not seem too difficult. The plotting of daily positions at sea is therefore not only a nautical ritual but also a psychological morale booster -- if one is heading in the right direction. But little did I know that there are more factors involved in ocean sailing than just distances covered. There are headwinds, gales, calms and gear failures to content with , which are all beyond a sailor's control. Nevertheless, it was a good mental game to play.

Being on a small boat, I was much closer to the ocean's surface to observe it. On calm days I would spend time watching little jellyfish and plankton floating by. I came across a couple of Japanese fishing floats and picked them up for souvenir. However, I also witnessed ample evidence of human impact on the fragile ocean, such as plastic, bottles, styrofoam in all shapes and sizes; and other objectional debris.

A

friendly visitor.

A

friendly visitor.

Of course, sea birds do keep the solitary sailor company from time to time. I became acquainted with a booby bird for a few days. He would circle the boat a few times, then fly higher and higher until he was a tiny speck of life. Then he disappeared, only to return and find the boat again the next day. I was jealous of his freedom and ability to wander with such simple elegance and without depending on excessive baggage like I was.

Occasionally there were moments great visual pleasure: double rainbows which barely touched the horizon, set against a storm-darkened sky miles away; Chalupa surfing down waves at great speeds with the company of playful dolphins; and those unforgettable sunsets performing magical light shows with the clouds. Even during times of rain and heavy weather I never ceased to be amazed and awed by the power and beauty of the sea, nature and the elements. I would put on my foulies, went on deck and braced myself safely and firmly with my back against the mast , just stood there, facing forward and watch Chalupa charging along. With each rhythmic roll it seemed like a serendipitous game of my body reacting to every motion of the waves with Chalupa as a facilitator and mediator between the two. And of course a sailboat has its own satisfying aesthetic. It is an elegant piece of art and engineering that interact magnificently with the elements to transform wind power into motion with amazing efficiency.

On the 11th day a sail was sighted. It turned out to be a Columbia 35, the "Solaris", competing in the Solo Transpac Race. I was delighted to speak to the skipper Ted Holland. He looked healthy from a boat length away, so I sailed on after our brief encounter.

Surfing

down the waves.

Surfing

down the waves.

Early one morning in my third week at sea I discovered a broken mainsheet shackle which I realized was too small to begin with. I fixed it right away, luckily, for afterwards we began to experience gale force winds of 25 to 35 knots and seas that were to last for six long, tiring days and nights. They were big and confused, coming from different directions. This created a problem for the self-steering vane. We would shoot down the face of each wave and start to surf, when another one would push us off-course 90 degrees. The Navik wind vane would then sprang into action and brought the boat back on course. It would do this day after day without complaint, only requiring a little oiling and adjustment from time to time. The knotmeter was once pegged at 10 knots coming down a good size wave and I could only speculate about our actual speed.

After four days in that kind of weather, sailing turned from fun to hard work and sometimes I began to wonder what in the world I was doing out there alone taking such a bashing. The motion and noise inside Chalupa was greatly amplified due to the fact that she was a small and light boat. I had no choice but to sail on unyielding and get used to my situation. No one made me do this; it was part of ocean sailing.

I decided to hand-steer Chalupa myself whenever I was up to it or when the conditions looked most likely to produce an accidental jibe or broach. It was mentally and physically exhausting but I was glad we were gaining much distance so I did not slow down. Also, by going too slowly I was afraid one of the breaking waves might catch up with us; in fact, a couple did but without causing any damage except making me worry. Since Chalupa was a light displacement, fin keeled boat, heaving-to was not too practical. With the wind on the quarter and having just the tiny storm jib up we were at times making 5 or 6 knots. Sun sights were out of the question with endless spray and a constantly disappearing horizon, not to mention the possibility of being thrown overboard on a very rolly deck, so I relied on my dead reckoning which I meticulously and constantly kept current .

The day before arrival at Kauai we were lucky to have moderate seas and fair weather, allowing me to established a good fix. Accordingly, I adjusted course for Hanalei Bay, Kauai.

As we neared land I grew more excited and anxious with every passing hour. I had made landfalls before after long periods at sea, but this time it was special. I was doing it all by myself. Kauai first appeared as a small speck on the horizon. I waited for a while, keeping an eye on it to make sure that it was not just a shadow from some low-lying cloud. After so many days at sea, the eyes can play tricks on one. But no, it indeed was land!

I could not help but feel a rush of pride in myself for accomplishing what I had always wanted to do for a long time. I had also learned the harsh truth that most worthwhile dreams cannot be achieved without sacrifice and hard work. It was a moment which I will cherish for many years to come.

I patted Chalupa and congratulated her for bringing me safely through all the miles. I was proud of her and my emotions at the time are difficult to describe.

At 5:30 p.m. (HST) on July 8, 1980 I dropped anchor in Hanalei Bay, Kauai, Hawaii, thus completing my first solo transpacific voyage in 20 days and 11 hours, almost to the minute.

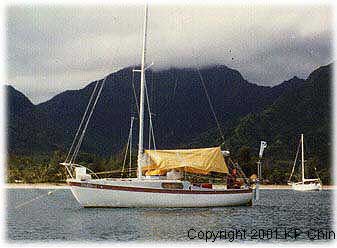

At

anchor Hanalei Bay.

At

anchor Hanalei Bay.

First published in Cruising World Magazine, December 1981

Copyright 1996 KP Chin.

All rights reserved.

Return to CruiseWeb HomePage or Expand Your Pocket Cruiser Page