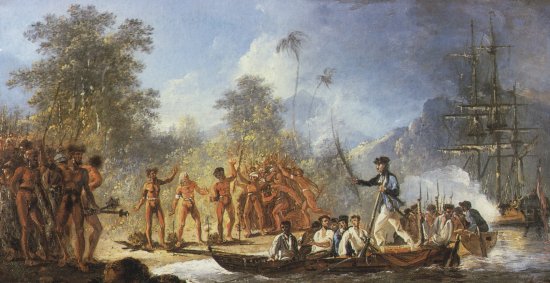

APRIL, 1774 At Resolution Bay, St. Christina - Part of the Marquesas Islands

At Resolution Bay, St. Christina - Part of the Marquesas Islands

JE: Those are an uncommon fine Race of people, both Men and Women: the former being generally better made, and the Women fairer, in common, than most we had seen. But our intercourse with them was unfortunately interupted by one of them being shot, for stealing an Iron Stanchion from the Ship's side, which displeased Capt. Cook much, as such acts always interupted all friendly intercourse with the Natives for two or three days.

Those are an uncommon fine Race of people, both Men and Women: the former being generally better made, and the Women fairer, in common, than most we had seen. But our intercourse with them was unfortunately interupted by one of them being shot, for stealing an Iron Stanchion from the Ship's side, which displeased Capt. Cook much, as such acts always interupted all friendly intercourse with the Natives for two or three days.

In a day or two the people recovered from their alarm, and after taking in part Water, getting a few pigs, and fruit, we departed, steering for Otaheite, where we arrived on the 22nd April, to the great joy of both ourselves, and our friends the Natives.

After securing properly, we got on shore at Point Venus - our Tent, Armourer's Forge, Casks, Sails etc. to repair, [with a] guard of Marines, and we proceeded to refit the Ship in every respect, standing much in need of it, after such a Navigation as we had experienced in the High Southern Latitudes.

And here we might be said to be at home, enjoying ourselves in perfect safety, and being as happy as people could be, at such a distance from England.

In the early part of the Voyage, Capt. Cook made all us young Gentlemen do the duty up aloft, the same as the Sailors, learning to hand and reef the sails, and steer the Ship, Exercise small arms, and so on, thereby making us good sailors, as well as good Officers... Here, when off duty, we formed little parties to go shooting, fishing, or walking, in perfect safety, at all times, the Natives coming on board in numbers, and going when they pleased. Many of the Women likewise staying on board day and Night. There was also this time a very brisk and regular trade carried on at the Tent, by Capt. Cook's directions, for Hogs, Fruit, and so on, so that the Ship's Company had fresh Pork daily, which was of the greatest service to us in point of health, tho we were certainly uncommonly healthy, all things considered.

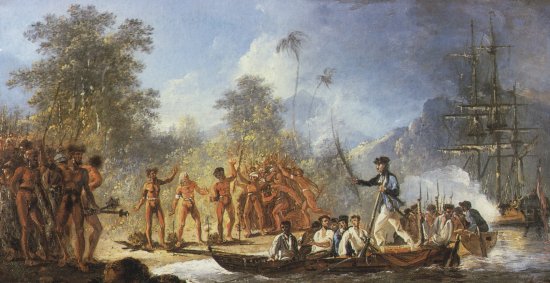

Part of the Tahitian Fleet: Gathering for an attack on the neighbouring island of Eimeo (Moorea).

We at this time had an opportunity of seeing a review of an Otaheite War Fleet, consisting of three hundred Sail, with all their Warriors on their Platforms, and fully armed. And which had a very grand appearance, such a one as we could by no means have expected, having streamers flying, and so on. At the same time a great many Men were drawn up on Shore, as if to oppose the Fleet in effecting a landing.

We found out by mere chance that the People of those Isles are exceedingly fond of Red Feathers. We got a great many of them as curiosities at Amsterdam and Rotterdam, where they gum them upon Cloth, some a yard, some half a yard, square, and we did not know what for. We bought them because we thought them handsom and curious. Some of those were shown at Otaheite, and both Men and Women were quite wild for them, so they were cut in small pieces, and became a valuable article of trade. I believe they are the red feathers of the Parrot and Parroquet.

Some of the War Canoes here are one Hundred feet long, and are two lashed together, by spars across.

Having now got the Ship compleated for Sea, and every thing on board, we took our final leave of our friends on the 14th May. When under sail, and saluting the King, one of our Gunners Mates slipped overboard (being an expert swimmer) intending to stay at Otaheite, they having promised a House, Land, and a Pretty Wife. After much difficulty we got him a board again (for he would have been a great loss to us) and proceeded on our way, stopping a few days at Huaheine, leaving it on the 22nd, and arriving at Ulietea on the 24th, where we staid to the 4th of June, and left then, steering Westward on discoveries. Our young friend and companion Oedidee stayed behind, which he was induced to do in consequence of Capt. Cook not being able to promise him that a ship should bring him back again. But it was not without the deepest distress that he left us; they promised him a Handsom young Wife, as one inducement to stay. He was a sensible, well disposed young Man, and had learnt all our different distinctions in the Ship, many words, etc., and been very happy with us, for 7 months.

JUNE 1774: We had more Plays acted here this time, and one thing I will observe to the credit of Women of Otaheite, and their Vertue, that, tho it is well known that the Single Women are very liberal of their favours, yet a Married Woman was never known to be got at, tho many tryals were made, with very high Offers, on purpose to try if it could be accomplished, but without effect. They always answered they were Married, with the greatest firmness.

The Cloth of the Society Isles is made from the Bark of a tree. They have Clubs, made of Black Wood like Black Ebony, curiously carved. We never eat bread while amongst those Isles, but lived upon Breadfruit, an excellent substitute, and is a fruit growing upon a tree, as large as a Child's head of 4 years old - and either broiled or boiled, is as good as bread, and could be a desirable thing in any country. We had at one time Three Hundred live Hogs on board, before we left Ulietea, which shews the great plenty we enjoyed amongst those friendly people.

We continued going Westward, discovering Four Islands.¹ Indeed, we discovered several Islands every time we came into those Seas, but which I shall not notice here, as I have placed them all on my Chart, and as they are only small, Low, and very dangerous, surrounded with Rocks and Reefs, the Sea breaking over them and forming beautiful Lagoons inside - very pretty for Boats to sail on, but extremely dangerous for ships to come near, many of them uninhabited.

One of those now discovered Cook called Savage Island, [Niue] from the circumstance of his being [nearly] killed, by one of the Natives rushing suddenly upon him with a Spear, and Cook's piece missing fire, the Man threw his Spear, which passed close over Cook's shoulder. At this moment young Mr Forster made his appearance, and fired, wounding the Man, who now retired, and joined his friends, with whom they had had some Skirmishing before. But had it not been for this providential circumstance, Cook's life would have been in most iminent danger.

JULY 1774: Passing on, we stopped a few days at Rotterdam, [Namuka] then proceeded to the N.W. until we came to a Large Group of Large Islands, called by Capt. Cook the New Hebrides, stretching 5° in Latitude. Most of them New Discoveries, but one or two had been seen before.

We sailed round and surveyed the Whole of the Group, and in endeavouring to find anchorage and Water at one of them called Eromanga, Capt. Cook and his Boat's Crew were in great danger of being all Killed. For on his rowing along Shore a great number of the Natives followed abreast of him, and in turning a low point of Land a Mile, or Mile and half, from the Ship, he found a Bay, which he thought likely. Therefore he pulled to the Shore, but still, from the great crowd of People, and all armed with Clubs and Spears, he hesitated. They beconed him to Land, but still he did not comply, not liking their appearance and manner. He had another small armed Boat with him.

The Gangboard was let down from the boats bows. At this Instant, several of the Natives rushed to the Gangboard and bows of the Boat, dragging her fairly on Shore. In this perilous situation a general Battle ensued, both boats firing to free the Boat and push her off. But more was done to effect this by a very fine young fellow of a Bowman, than half the Musquets, for he instantly spring into the midst of them, near the bow of the Boat (his Boat) and stabbed and hooked away at so desperate a rate that he contributed much to the liberation of the Boat, and they got her off with only one Man badly wounded, by having a Spear drove through his jaw.

Others got hirts, but not materialy so. How many of the Natives they killed or wounded they could not tell, but of course, several must have been both. We saw the firing from the Ship, but [could] not render any assistance, so that all depended on themselves.

Cook, landing at the Island of Tanna.

When the Boats came on board, we sailed away for another Island called Tanna, which we had observed before. In the night we had heard loud Noises, like discharges of Cannon, and we saw a light, which we afterwards found proceeded from a Volcano, throwing up vast columns of Fire and Smoke.

AUGUST 1774: Standing in for the Island, we observed an opening. A boat being sent to examine it soon reported a Very Fine Harbour (which Cook called Port Resolution) into which we stood, and anchored, it appearing to afford every thing we wanted, Viz, safety for the Ship, and Wood and Water. The Entrance into this Harbour is not more than 300 fathom wide, and when in, it is a most beautiful Harbour, well wooded and very populous. Indeed, all those Islands are, the Natives appearing in great crowds in canoes, all well armed, with Bows, Arrows, Clubs, and Spears (or darts - 15 or 16 feet long) of a very dangerous kind, being barbed for half a yard from the Point. The Arrows are many of them also barbed, and with those Weapons seeming very active and daring, made it necessary that we should proceed with caution, as we intended to stay some time, to refit the Ship, take in Wood and Water, and so on.

Therefore Capt. Cook fixed a plan to secure a landing without loss of Men, for on landing in the evening, in a single Boat, where he found Water, he had every reason to think if he stayed long [the inhabitants] would attack him. He therefore had the ship secured broadside on the Beach, and within Musquet shot of the Place we intended landing at, and all the Great Guns pointed to the same effect (but over it) as well as Wall pieces.

He then went with three Boats Manned and Armed with the Marines to the Shore, where he found a vast crowd of Natives drawn up in two lines (every Man armed) a little distance asunder, and some fruit laid between, as if to intice our people to land and take them, at the same time beconing them to land. But Capt. Cook had been too near losing his life lately, by fair signs, to be caught in the trap again.

He therefore desired (by signs) that they would fall back, and leave more room, but they paid no attention. He then fired a Musquet over their heads - this they did not mind, but brandished their Weapons in a threatening attitude. One man smacked his backside at them. Capt. Cook then fired three Musquets over their heads as a sign also to the Ship, to fire the Great Guns, as thinking less Mischief would be done by that means than if he fired amongst them with all his small arms, and the noise would have better effect in frightening them, which proved the case, for we soon cleared the Beach, not a Man to be seen.

Capt. Cook then landed, marked out the ground, and fixed Sentrys. We proceeded with our Wooding and Watering, and the Natives gained confidence by degrees, and came to us again, but always armed, so that both parties were always prepared. Both from their numbers, and dangerous Weapons, we never wished to have an occasion to use Arms, for theirs were equally destructive in their hands.

They had Clubs of Black Ebony, Bows, Arrows, Spears, Slings, and stones, the Spears and Arrows many of them poisoned and barbed half a yard. With their Bows they could shoot a bird in the bush, and I have seen 6 of them, placed in a line, at 20 yards distance, and they have fixed every Spear in a soft Coconut. I have known them strike a fish only a foot long, at 20 yards distance in the Water, with a Spear.

Such Men were not to be trusted or trifled with. Very little intercourse was had with them beyond the Beach, or just within the skirts of the Woods, to shoot birds, and then they came out covered with soot and ashes from the Volcano, which fell from the trees...

The Volcano [Mt. Yasua] was only a little distance from us, behind a Moderate range of Hills, and had a grand and curious effect at night. The Water came through the Mountain, on the Beach, so hot as to boil an Egg. Our deck was covered every Morning with ashes from it, as it would send forth tremendous Roars, and columns of fire and smoke every night...

SEPTEMBER 1774: Having compleated the Ship in every thing necessary, we got every thing on board, and proceeded to sea, steering round Tanna to the N.E. and compleating the Survey of all the Islands. On the 31st August we left the Northern Island, steering S.W. until the 4th September, when we discovered a fine Island, of great extent, and high - being 200 miles Long, and 30 miles Broad.

On the 5th we anchored in Balade Bay, with a Reef, and Island called Observatory Island, in Lat. 20° 17' Long. 164° 41' E., Captain Cook calling the whole country New Caledonia.

Here we stayed a few days to examine the Country, Natives, etc. The country is High, and wooded. The People, both Men and Women, are tall, robust, and well made, but large Limbed and heavy looking; the Men generally approaching 6 foot, some 6' 3 or 4 inches, the Women in proportion - but mild, humain, and civil. Their Weapons are Clubs, Slings, Stones, and Spears, of a heavier kind than those of Tanna.

During their visit, a Hadley's Quadrant was used to take measurements of a solar-eclipse and the ship's Butcher, Simon Monk, died from injuries received when he fell down the fore-hatchway one evening. Cook made several friends on the Island, including the Chief, and invited them to dinner on board the ship. They were not curious to sample the European menu of pea-soup, salt beef and pork, but they did eat some yams (called in their tongue Oobee), which were left over from trading with other islands. The ship was often overcrowded and there were daily trips to the Island, taking observations and naming various landmarks.

CJC: In the afternoon [of the 7th], I made a little excursion alongshore to the westward, in company with Mr. Wales. This afternoon, a fish being struck by one of the natives near the watering-place, my clerk purchased it, and sent it to me after my return on board. It was of a new species, something like a sun-fish, with a large, long, ugly head. Having no suspicion of its being of a poisonous nature, we ordered it to be dressed for supper; but, very luckily, the operation of drawing and describing took up so much time, that it was too late, so that only the liver and roe were dressed, of which the two Mr. Forsters and myself did but taste. About three o'clock in the morning, we found ourselves seized with an extra-ordinary weakness and numbness all over our limbs: I had almost lost the sense of feeling, nor could I distinguish between light and heavy bodies, of such as I had strength to move; a quart pot full of water and a feather being the same in my hand. We each of us took an emetic, and after that a sweat, which gave us much relief. In the morning, one of the pigs which had eaten the entrails was found dead. When the natives came on board, and saw the fish hang up, they immediately gave us to understand it was not wholesome food, and expressed the utmost abhorrence of it; though no one was observed to do this when the fish was to be sold, or even after it was purchased...

After breakfast [on the 9th], a party of men was sent ashore to make brooms; but myself and the two Mr. Forsters were confined on board, though much better, a good sweat having had a happy effect. In the afternoon, a man was seen, both ashore and alongside the ship, said to be as white as any European. From the account I had of him (for I did not see him), his whiteness did not proceed from hereditary descent, but from chance or some disease; and such have been seen at Otaheite and the Society Isles². A fresh easterly wind, and the ship lying a mile from the shore, did not hinder these good natured people from swimming off to us in shoals of twenty or thirty, and returning the same way.

On the 10th, a party was on shore as usual; and Mr. Forster so well recovered as to go out botanizing. In the evening of the 11th the boats returned, when I was informed of the following circumstances. From an elevation which they reached the morning they set out, they had a view of the coast. Mr. Gilbert was of opinion that they saw the termination of it to the west, but Mr. Pickersgill thought not; though both agreed that there was no passage for the ship that way. From this place, accompanied by two of the natives, they went to Balabea, which they did not reach till after sunset, and left again next morning before sunrise; consequently this was a fruitless expedition, and the two following days were spent getting up to the ship. As they went down to the isle, they saw abundance of turtle, but the violence of the wind and sea made it impossible to strike any. The cutter was near being lost, by suddenly filling with water, which obliged them to throw several things overboard before they could free her and stop the leak she had sprung. From a fishing canoe, which they met coming in from the reefs, they got as much fish as they could eat; and they were received by Teabi, the chief of the isle of Balabea, and the people, who came in numbers to see them, with great courtesy. In order not to be too much crowded, our people drew a line on the ground, and gave the others to understand they were not to come within it. This restriction they observed; and one of them, soon after, turned it to his own advantage: for happening to have a few cocoa-nuts, which one of our people wanted to buy, and he was unwilling to part with, he walked off, and was followed by the man who wanted them. On seeing this, he sat down on the sand, made a circle round him, as he had seen our people do, and signified that the other was not to come within it; which was accordingly observed. As this story was well attested, I thought it not unworthy of a place in this journal.

Early in the morning of the 12th, I ordered the carpenter to work, to repair the cutter, and the water to be replaced which we had expended the three preceding days... In the afternoon I went on shore, and, on a large tree, which stood close to the shore, near the watering-place, had an inscription cut, setting forth the ship's name, date, &c., as a testimony of our being the first discoverers of this country, as I had done at all others at which we had touched, where this ceremony was necessary. This being done, we took leave of our friends, and returned on board, when I ordered all the boats to be hoisted in, in order to be ready to put to sea in the morning.

JE: Leaving Balade Bay, we steered along the coast Southward, surveying it as we went along, observing in places very curious trees, like ships under sail, particularly on an Island which Cook called the Isle of Pines, from finding that the Trees were a very curious Pine Tree, growing high, and spreading their branches wide.

Leaving Balade Bay, we steered along the coast Southward, surveying it as we went along, observing in places very curious trees, like ships under sail, particularly on an Island which Cook called the Isle of Pines, from finding that the Trees were a very curious Pine Tree, growing high, and spreading their branches wide.

In sailing round the Isle of Pines in the Evening, we found ourselves in a most dangerous situation, for the Man at the Mast Head called out: Breakers ahead. We hauled up several points, still Breakers ahead. In fact, we found that we had been running into a Net of Breakers (or Reef), and no way out, but as we had come in, which was now right in the Wind's Eye. The Winds increased as night came on, and every way we stood for an hour, the Roaring of the Breakers was heard. So that was a most anxious and perilous Night.

At last daylight appeared, when we bore up, in clear Water, for a small Island with some of those trees on it, and near the mainland, where we came to an anchor, landed, and cut down some of the trees, and got them on board for Spars. Many might be got, to make Ship's Masts if wanted, and the only place in those Seas, except at New Zealand, where a Mast could be replaced.

We sailed again on the 30th, and in going out, had it not been for the intervention of providence, a good look out, and quick working, we must still have been lost, for the Breakers were seen close under our Bows, when the Ship was thrown instantly about, and by that means saved, and proceeded to Sea. Leaving the other side of the Country unexplored, but we saw enough of it to be certain it was not more than 30 Miles broad.

OCTOBER 1774: We continued steering to the N.E. til the 10th of October, when we discovered a New Island, in Lat. 29° 2' Long. 168° 16' East; pretty high, and 15 Miles round.

CJC: I named it Norfolk Isle, in honour of the noble family of Howard... Soon after we discovered the isle, we sounded in twenty-two fathoms on a bank of coral sand; after this we continued to sound, and found not less than twenty-two, or more than twenty-four fathoms (except near the shore), and the same bottom mixed with broken shells. After dinner, a party of us embarked in two boats, and landed on the island, without any difficulty, behind some large rocks which lined part of the coast on the N.E. side. We found it uninhabited, and were undoubtedly the first that ever set foot on it. We observed many trees and plants common at New Zealand; and in particular, the flax-plant, which is rather more luxuriant here than in any part of that country: but the chief produce is a sort of spruce pine, which grows in great abundance, and to a large size, many of the trees being as thick, breast-high, as two men could fathom, and exceedingly straight and tall...

The coast does not want fish. While we were on shore, the people in the boats caught some which were excellent. I judged that it was high water at the full and change, about one o'clock, and that the tide rises and falls upon a perpendicular about four or five feet. The approach of night brought us all on board, when we hoisted in the boats; and stretching to E.N.E. (with the wind at S.E.) till midnight, we tacked and spent the remainder of the night making short boards.

Next morning, at sunrise, we made sail, stretching to S.S.W., and weathered the island, on the south side of which lie two isles, that serve as roosting and breeding places for birds... After leaving Norfolk Isle, I steered for New Zealand, my intention being to touch at Queen Charlotte's Sound, to refresh my crew, and put the ship in a condition to encounter the southern latitudes.

On the 17th, at daybreak, we saw Mount Egmont, which was covered with everlasting snow, bearing S.E. ½ E. Our distance from the shore was about eight leagues; and on sounding, we found seventy fathoms water, a muddy bottom. The wind soon fixed in the western board, and blew a fresh gale, with which we steered S.S.E. for Queen Charlotte's Sound, with a view of falling in with Cape Stephens.

JE: We anchored safe in Ship Cove, on the 18th of October. Here we prepared to refit and repair the Ship in every respect, so as to enable her to meet the Weather, in the high Latitudes we meant to run in our course towards Cape Horn.

We anchored safe in Ship Cove, on the 18th of October. Here we prepared to refit and repair the Ship in every respect, so as to enable her to meet the Weather, in the high Latitudes we meant to run in our course towards Cape Horn.

In the meantime, we occasionally amused ourselves in Fishing, Shooting, and so on, not withstanding we had daily visits from our Savage Cannibal friends. But our shooting range did not extend beyond a Mile or Two in the Woods, where we met with Parrots, and Poiebirds³ plenty, and both beautys in their kind. If we found bad sport we had only to wound one Parrot, and set our foot on its leg, and squealing and screaming it would bring a dozen over our heads.

I should have observed before that the Whole of New Zealand is covered with Wood of different kinds, and of the largest growth, such as would make Lower masts for Men of War. I have seen many 6 or 8 feet round, Man height from the ground. One kind is much like Mahogany, and would make handsom furniture.

At all times while here we used to get Scurvy grass and wild Cellery out of the Woods, and boil [them] up with our Peas, as Antiscorbutics.

Soon after our Arrival here, the Natives told us a story about a Ship being lost, and fighting, Men killed, etc., but we could not make out anything satisfactory, little suspecting that it related to the Adventure, but which we afterwards found it did.

Queen Charlotte Sound is in very fine Climate, being in Lat. 41° 6' Long. 174° 23' E.

The same Gunner (John Marra) attempted to leave us here that did at Otaheite, and Cook declared that if he was not well assured that the fellow would be killed and Eat, before Morning, he would have let him go.

CJC: I had now made the circuit of the Southern Ocean in a high latitude, and traversed it in such a manner as to leave not the least room for the possibility of there being a continent, unless near the pole, and out of reach of navigation. By twice visiting the tropical sea, I had not only settled the situation of some old discoveries, but made there many new ones, and left, I conceive, very little more to be done even in that part. Thus I flatter myself that the intention of the voyage has, in every respect, been fully answered; the southern hemisphere sufficiently explored; and a final end put to the searching after a southern continent, which has, at times, engrossed the attention of some of the maritime powers for near two centuries past, and been a favourite theory amongst the geographers of all ages.

The South Atlantic Passage, and the Return Home

¹ They sailed past Maupiti, Borabora, Motu Iti, Mopihaa, and Palmerston Island, before landing on Niue (Savage Island) on June 22.

¹ They sailed past Maupiti, Borabora, Motu Iti, Mopihaa, and Palmerston Island, before landing on Niue (Savage Island) on June 22.

² Sightings of white-skinned natives have not been uncommon: Wafer met with Indians in the Isthmus of Darien that were "the colour of a white horse".

³ The New Zealand Tui was given this name by the crew because its tuft of white feathers at the throat reminded them of Tahitian ear-rings - 'poie'.

© 1999 Michael Dickinson

[ Home | The 1st Voyage | The 2nd Voyage | The 3rd & Final Voyage | Next ]

This page hosted by  Get your own Free Home Page

Get your own Free Home Page