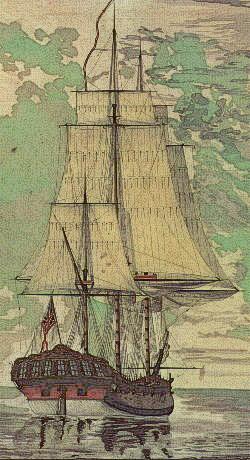

NAVES: RESOLUTION, JAC. COOK, PR.

CJC: As I did not give up my design of touching at Eimeo, at daybreak, in the morning of the 30th, after leaving Otaheite, I stood for the north end of the island; the harbour, which I wished to examine, being at that part of it. Omai, in his canoe, having arrived there long before us, had taken some necessary measures to show us the place. However, we were not without pilots, having several men of Otaheite on board, and not a few women. Not caring to trust entirely to these guides, I sent two boats to examine the harbour, and, on their making the signal for safe anchorage, we stood in with the ships, and anchored close up to the head of the inlet, in ten fathoms water, over a bottom of soft mud, and moored with a hawser fast to the shore.

CJC: As I did not give up my design of touching at Eimeo, at daybreak, in the morning of the 30th, after leaving Otaheite, I stood for the north end of the island; the harbour, which I wished to examine, being at that part of it. Omai, in his canoe, having arrived there long before us, had taken some necessary measures to show us the place. However, we were not without pilots, having several men of Otaheite on board, and not a few women. Not caring to trust entirely to these guides, I sent two boats to examine the harbour, and, on their making the signal for safe anchorage, we stood in with the ships, and anchored close up to the head of the inlet, in ten fathoms water, over a bottom of soft mud, and moored with a hawser fast to the shore.We had no sooner anchored than the ships were crowded with the inhabitants, whom curiosity alone brought on board; for they had nothing with them for the purposes of barter. But, the next morning, this deficiency was supplied; several canoes then arriving from more distant parts, which brought with them abundance of bread-fruit, cocoa-nuts, and a few hogs. These they exchanged for hatchets, nails, and beads, for red feathers were not so much sought after here as at Otaheite. The ship being a good deal pestered with rats, I hauled her within thirty yards of the shore, as near as the depth of water would allow, and made a path for them to get to the land, by fastening hawsers to the trees. It is said that this experiment has sometimes succeeded; but, I believe, we got clear of very few, if any, of the numerous tribe that haunted us.

In the morning of the 2d, Maheine, the chief of the island, paid me a visit. He approached the ship with great caution, and it required some persuasion to get him on board. Probably, he was under some apprehensions of mischief from us, as friends of the Otaheiteans; these people not being able to comprehend how we can be friends with any one, without adopting, at the same time, his cause against his enemies. Maheine was accompanied by his wife, who, as I was informed, is sister to Oamo of Otaheite, of whose death we had an account while we were at this island. I made presents to both of them, of such things as they seemed to set the highest value upon; and after a stay of about half an hour, they went away. Not long after, they returned with a large hog, which they meant as a return for my present; but I made them another present to the full value of it. After this, they paid a visit to Captain Clerke.

This chief, who with a few followers has made himself in a manner independent of Otaheite, is between forty and fifty years old. He is bald-headed, which is rather an uncommon appearance in these islands at that age. He wore a kind of turban, and seemed ashamed to show his head. But whether they themselves considered this deficiency of hair as a mark of disgrace, or whether they entertained a notion of our considering it as such, I cannot say. We judged that the latter supposition was the truth, from this circumstance, that they had seen us shave the head of one of their people, whom we had caught stealing. They therefore concluded that this was the punishment usually inflicted by us upon all thieves; and one or two of our gentlemen, whose heads were not overburthened with hair, we could observe, lay under violent suspicions of being tetos. In the evening, Omai and I mounted on horseback, and took a ride along the shore to the eastward. Our train was not very numerous, as Omai had forbid the natives to follow us; and many complied, the fear of giving offence getting the better of their curiosity. Towha had stationed his fleet in this harbour; and though the war lasted but a few days, the marks of its devastation were everywhere to be seen. The trees were stripped of their fruit; and all the houses in the neighbourhood had been pulled down or burnt.

Having employed two or three days in getting up all our spirit-casks to tar their heads, which we found necessary to save them from the efforts of a small insect to destroy them, we hauled the ship off into the stream on the 6th, in the morning, intending to put to sea the next day; but an accident happened that prevented it, and gave me a good deal of trouble. We had sent our goats ashore in the daytime to graze, with two men to look after them; notwithstanding which precaution, the natives had contrived to steal one of them this evening. The loss of this goat would have been of little consequence, if it had not interfered with my views of stocking other islands with these animals; but this being the case, it became necessary to recover it if possible. The next morning we got intelligence, that it had been carried to Maheine, the chief, who was at this time at Parowroah harbour. Two old men offered to conduct any of my people whom I might think proper to send to him, to bring back the goat. Accordingly, I despatched them in a boat, charged with a threatening message to Maheine, if the goat was not immediately given up to me, and also the thief.

It was only the day before, that this chief had requested me to give him two goats. But, as I could not spare them, unless at the expense of other islands that might never have another opportunity to get any, and had, besides, heard that there were already two upon this island, I did not gratify him. However, to show my inclination to assist his views in this respect, I desired Tidooa, an Otaheite chief who was present, to beg Otoo, in my name, to send two of these animals to Maheine; and, by way of insuring a compliance with this request, I sent to Otoo, by this chief, a large piece of red feathers, equal to the value of the two goats that I required. I expected that this arrangement would have been satisfactory to Maheine and all the other chiefs of the island; but the event showed that I was mistaken...

At Eimeo we abundantly supplied the ships with fire-wood. We had not taken in any at Otaheite, where the procuring this article would have been very inconvenient; there not being a tree at Matavai but what is useful to the inhabitants. We also got here good store of refreshments, both in hogs and vegetables; that is, bread-fruit and cocoa-nuts; little else being in season. I do not know that there is any difference between the produce of this island and of Otaheite; but there is a very striking difference in their women, that I can by no means account for. Those of Eimeo are of low stature, have a dark hue, and, in general, forbidding features. If we met with a fine woman amongst them, we were sure, upon inquiry, to find that she had come from some other island.

The general appearance of Eimeo is very different from that of Otaheite. The latter rising in one steep hilly body, has little low land, except some deep valleys; and the flat border that surrounds the greatest part of it, toward the sea. Eimeo, on the contrary, has hills running in different directions, which are very steep and rugged, leaving in the inter-spaces very large valleys, and gently-rising grounds about their sides. These hills, though of a rocky disposition, are in general covered almost to their tops with trees; but the lower parts, on the sides, frequently only with fern. At the bottom of the harbour where we lay, the ground rises gently to the foot of the hills which run across nearly in the middle of the island; but its flat border, on each side, at a very small distance from the sea, becomes quite steep. This gives it a romantic cast, which renders it a prospect superior to anything we saw at Otaheite. The soil, about the low grounds, is a yellowish and pretty stiff mould; but, upon the lower hills, it is blacker and more loose; and the stone that composes the hills is, when broken, of a bluish colour, but not very compact texture, with some particles of glimmer interspersed. These particulars seem worthy of observation. Perhaps the reader will think differently of my judgment, when I add, that, near the station of our ships, were two large stones, or rather rocks, concerning which the natives have some superstitious notions. They consider them as Eatooas, or divinities; saying that they are brother and sister, and that they came, by some supernatural means, from Ulietea.

CJC: Having left Eimeo, with a gentle breeze and fine weather, at daybreak the next morning we saw Huaheine, extending from south-west by west, half west, to west by north. At noon we anchored at the north entrance of Owharre harbour, which is on the west side of the island. The whole afternoon was spent in warping the ships into a proper berth, and mooring. Omai entered the harbour just before us, in his canoe, but did not land. Nor did he take much notice of any of his countrymen, though many crowded to see him; but far more of them came off to the ships, insomuch that we could hardly work on account of their numbers. Our passengers presently acquainted them with what we had done at Eimeo, and multiplied the number of houses and canoes that we had destroyed, by ten at least. I was not sorry for this exaggerated account; as I saw that it made a great impression upon all who heard it; so that I had hopes it would induce the inhabitants of this island to behave better to us than they had done during my former visits. While I was at Otaheite, I had learned that my old friend Oree was no longer the chief of Huaheine; and that, at this time, he resided at Ulietea. Indeed, he never had been more than regent during the minority of Taireetareea, the present Earee rahie; but he did not give up the regency till he was forced. His two sons, Opoony and Towha, were the first who paid me a visit, coming on board before the ship was well in the harbour, and bringing a present with them.

Our arrival brought all the principal people of the island to our ships on the next morning, being the 13th. This was just what I wished, as it was high time to think of settling Omai; and the presence of these chiefs, I guessed, would enable me to do it in the most satisfactory manner. He now seemed to have an inclination to establish himself at Ulietea; and if he and I could have agreed about the mode of bringing that plan to bear, I should have had no objection to adopt it. His father had been dispossessed by the men of Bolabola, when they conquered Ulietea, of some land in that island; and I made no doubt of being able to get it restored to the son in an amicable manner. For that purpose it was necessary that he should be upon good terms with those who now were masters of the island; but he was too great a patriot to listen to any such thing, and was vain enough to suppose that I would reinstate him in his forfeited lands by force. This made it impossible to fix him at Ulietea, and pointed out to me Huaheine as the proper place. I therefore resolved to avail myself of the presence of the chief men of the island, and to make this proposal to them.

After the hurry of the morning was over, we got ready to pay a formal visit to Taireetarea, meaning then to introduce his business. Omai dressed himself very properly on the occasion, and prepared a handsome present for the chief himself, and another for his Eatooa. Indeed, after he had got clear of the gang that surrounded him at Otaheite, he behaved with such prudence as to gain respect. Our landing drew most of our visitors from the ships; and they, as well as those that were on shore, assembled in a large house. The concourse of people, on this occasion, was very great; and amongst them, there appeared to be a greater proportion of personable men and women than we had ever seen in one assembly at any of these new islands. Not only the bulk of the people seemed in general much stouter and fairer than those of Otaheite, but there was also a much greater number of men who appeared to be of consequence, in proportion to the extent of the island; most of whom had exactly the corpulent appearance of the chiefs of Wateeo. We waited some time for Taireetareea, as I would do nothing till the Earee rahie came; but when he appeared, I found that his presence might have been dispensed with, as he was not above eight or ten years of age. Omai, who stood at a little distance from this circle of great men, began with making his offering to the gods, consisting of red feathers, cloth, &c. Then followed another offering, which was to be given to the gods by the chief; and, after that, several other small pieces and tufts of red feathers were presented. Each article was laid before one of the company, who, I understood, was a priest, and was delivered with a set speech or prayer, spoken by one of Omai's friends, who sat by him, but mostly dictated by himself. In these prayers, he did not forget his friends in England, nor those who had brought him safe back. The Earee rahie no Pretane, Lord Sandwich, Toote, Tatee¹ were mentioned in every one of them. When Omai's offerings and prayers were finished, the priest took each article, in the same order in which it had been laid before him, and after repeating a prayer, sent it to the morai; which, as Omai told us, was at a great distance, otherwise the offerings would have been made there.

These religious ceremonies having been performed, Omai sat down by me, and we entered upon business, by giving the young chief my present, and receiving his in return; and, all things considered, they were liberal enough on both sides. Some arrangements were next agreed upon, as to the manner of carrying on the intercourse betwixt us; and I pointed out the mischievous consequences that would attend their robbing us, as they had done during my former visits. Omai's establishment was then proposed to the assembled chiefs.

He acquainted them, "That he had been carried by us into our country, where he was well received by the great king and his Earees, and treated with every mark of regard and affection, while he staid amongst us; that he had been brought back again, enriched by our liberality with a variety of articles, which would prove very useful to his countrymen; and that, besides the two horses which were to remain with him, several other new and valuable animals had been left at Otaheite, which would soon multiply, and furnish a sufficient number for the use of all the islands in the neighbourhood. He then signified to them, that it was my earnest request, in return for all my friendly offices, that they would give him a piece of land, to build a house upon, and to raise provisions for himself and servants; adding, that, if this could not be obtained for him at Huaheine, either by gift or by purchase, I was determined to carry him to Ulietea² and fix him there".

Perhaps I have here made a better speech for my friend than he actually delivered; but these were the topics I dictated to him. I observed, that what he concluded with, about carrying him to Ulietea, seemed to meet with the approbation of all the chiefs; and I instantly saw the reason. Omai had, as I have already mentioned, vainly flattered himself, that I meant to use force in restoring him to his father's lands in Ulietea, and he had talked idly, and without any authority from me, on this subject, to some of the present assembly; who dreamed of nothing less than a hostile invasion of Ulietea, and of being assisted by me to drive the Bolabola men out of that island. It was of consequence, therefore, that I should undeceive them; and in order to do this, I signified, in the most peremptory manner, that I neither would assist them in such an enterprise, nor suffer it to be put in execution, while I was in their seas; and that, if Omai fixed himself in Ulietea, he must be introduced as a friend, and not forced upon the Bolabola men as their conqueror.

This declaration gave a new turn to the sentiments of the council. One of the chiefs immediately expressed himself to this effect: "That the whole island of Huaheine, and everything in it, were mine; and that, therefore, I might give what portion of it I pleased to my friend". Omai, who, like the rest of his countrymen, seldom sees things beyond the present moment, was greatly pleased to hear this; thinking, no doubt, that I should be very liberal, and give him enough. But to offer what it would have been improper to accept, I considered as offering nothing at all; and, therefore, I now desired, that they would not only assign the particular spot, but also the exact quantity of land which they would allot for the settlement. Upon this, some chiefs, who had already left the assembly, were sent for, and after a short consultation among themselves, my request was granted, by general consent, and the ground immediately pitched upon, adjoining to the house where our meeting was held. The extent, along the shore of the harbour, was about two hundred yards, and its depth, to the foot of the hill, somewhat more; but a proportional part of the hill was included in the grant.

This business being settled to the satisfaction of all parties, I set up a tent ashore, established a post, and erected the observatories. The carpenters of both ships were also set to work, to build a small house for Omai, in which he might secure the European commodities that were his property. At the same time, some hands were employed in making a garden for his use; planting shaddocks, vines, pine-apples, melons, and the seeds of several other vegetable articles, all of which I had the satisfaction of observing to be in a flourishing state before I left the island. Omai now began seriously to attend to his own affairs, and repented heartily of his ill-judged prodigality while at Otaheite. He found at Huaheine, a brother, a sister, and a brother-in-law, the sister being married. But these did not plunder him, as he had lately been by his other relations. I was sorry, however, to discover, that though they were too honest to do him any injury, they were of too little consequence in the island to do him any positive good. They had neither authority nor influence to protect his person or his property; and in that helpless situation, I had reason to apprehend that he ran great risk of being stripped of everything he had got from us, as soon as he should cease to have us within his reach, to enforce the good behaviour of his countrymen, by an immediate appeal to our irresistible power.

A man who is richer than his neighbours is sure to be envied by numbers, who wish to see him brought down to their own level. But in countries where civilisation, law, and religion impose their restraints, the rich have a reasonable ground of security. And, besides, there being in all such communities a diffusion of property, no single individual need fear that the efforts of all the poorer sort can ever be united to injure him, exclusively of others who are equally the objects of envy. It was very different with Omai. He was to live amongst those who are strangers, in a great measure, to any other principle of action, besides the immediate impulse of their natural feelings. But what was his principal danger? He was to be placed in the very singular situation of being the only rich man in the community to which he was to belong; and having, by a fortunate connexion with us, got into his possession an accumulated quantity of a species of treasure which none of his countrymen could create, by any art or industry of their own, - while all coveted a share of this envied wealth, it was natural to apprehend, that all would be ready to join in attempting to strip its sole proprietor. To prevent this, if possible, I desired him to make a proper distribution of some of his moveables to two or three of the principal chiefs, who being thus gratified themselves, might be induced to take him under their patronage, and protect him from the injuries of others. He promised to follow my advice, and I heard, with satisfaction, before I sailed, that this very prudent step had been taken. Not trusting, however, entirely to the operation of gratitude, I had recourse to the more forcible motive of intimidation. With this view, I took every opportunity of notifying to the inhabitants, that it was my intention to return to their island again, after being absent the usual time; and that if I did not find Omai in the same state of security in which I was now to leave him, all those whom I should then discover to have been his enemies, might expect to feel the weight of my resentment. This threatening declaration will probably have no inconsiderable effect, for our successive visits of late years have taught these people to believe that our ships are to return at certain periods; and while they continue to be impressed with such a notion, which I thought it a fair stratagem to confirm, Omai has some prospect of being permitted to thrive upon his new plantation...

CJC: Omai's house being nearly finished, many of his movables were carried ashore on the 26th. Amongst a variety of other useless articles was a box of toys, which, when exposed to public view, seemed greatly to please the gazing multitude; but as to his pots, kettles, dishes, plates, drinking-mugs, glasses, and the whole train of our domestic accommodations, hardly any one of his countrymen would so much as look at them. Omai himself now began to think that they were of no manner of use to him, - that a baked hog was more savoury food than a boiled one, - that a plantain-leaf made as good a dish or plate as pewter, - and that a cocoa-nut shell was as convenient a goblet as a black-jack; and, therefore, he very wisely disposed of as many of these articles of English furniture for the kitchen and pantry, as he could find purchasers for, amongst the people of the ships, receiving from them, in return, hatchets, and other iron tools, which had a more intrinsic value in this part of the world, and added more to his distinguishing superiority over those with whom he was to pass the remainder of his days. In the long list of the presents bestowed upon him in England, fire-works had not been forgot. Some of these we exhibited in the evening of the 28th, before a great concourse of people, who beheld them with a mixture of pleasure and fear; what remained after the evening's entertainment, were put in order and left with Omai, agreeably to their original destination. Perhaps we need not lament it as a serious misfortune, that the far greater share of this part of his cargo had been already expended in exhibitions at other islands, or rendered useless by being kept so long.

As soon as Omai was settled in his new habitation, I began to think of leaving the island, and got everything off from the shore this evening except the horse and mare, and a goat big with kid, which were left in the possession of our friend, with whom we were now finally to part. I also gave him a boar and two sows of the English breed, and he had got a sow or two of his own. The horse covered the mare while we were at Otaheite, so that I consider the introduction of a breed of horses into these islands as likely to have suceeded by this valuable present.

The history of Omai will, perhaps, interest a very numerous class of readers, more than any other occurrence of a voyage, the objects of which do not, in general, promise much entertainment. Every circumstance, therefore, which may serve to convey a satisfactory account of the exact situation in which he was left, will be thought worth preserving; and the following particulars are added, to complete the view of his domestic establishment. He had picked up at Otaheite four or five Toutous; the two New Zealand youths remained with him, and his brother and some others joined him at Huaheine, so that his family consisted already of eight or ten persons, if that can be called a family to which not a single female as yet belonged, nor, I doubt, was likely to belong, unless its master became less volatile; at present, Omai did not seem at all disposed to take unto himself a wife. The house which we erected for him was twenty-four feet by eighteen, and ten feet high. It was composed of boards, the spoils of our military operations at Eimeo; and, in building it, as few nails as possible were used, that there might be no inducement, from the love of iron, to pull it down. It was settled that, immediately after our departure, he should begin to build a large house after the fashion of his country, one end of which was to be brought over that which we had erected so as to enclose it entirely for greater security. In this work, some of the chiefs promised to assist him; and if the intended building should cover the ground which he marked out, it will be as large as most upon the island³.

His European weapons consisted of a musket, bayonet, and cartouch-box; a fowling-piece, two pairs of pistols, and two or three swords or cutlasses. The possession of these made him quite happy, which was my only view in giving him such presents; for I was always of opinion that he would have been happier without fire-arms, and other European weapons, than with them; as such implements of war, in the hands of one whose prudent use of them I had some grounds for mistrusting, would rather increase his dangers than establish his superiority. After he had got on shore everything that belonged to him, and was settled in his house, he had most of the officers of both ships, two or three times, to dinner; and his table was always well supplied with the very best provisions that the island produced. Before I sailed, I had the following inscription cut upon the outside of his house:-

On the 2d of November, at four in the afternoon, I took the advantage of a breeze which then sprung up at east, and sailed out of the harbour. Most of our friends remained on board till the ships were under sail, when, to gratify their curiosity, I ordered five guns to be fired. They then all took their leave, except Omai, who remained till we were at sea. We had come to sail by a hawser fastened to the shore. In casting the ship it parted, being cut by the rocks, and the outer end was left behind, as those who cast it off did not perceive that it was broken; so that it became necessary to send a boat to bring it on board. In this boat Omai went ashore, after taking a very affectionate farewell of all the officers. He sustained himself with a manly resolution till he came to me. Then his utmost efforts to conceal his tears failed; and Mr. King, who went in the boat, told me that he wept all the time in going ashore.

It was no small satisfaction to reflect that we had brought him safe back to the very spot from which he was taken. And yet, such is the strange nature of human affairs, that it is probable we left him in a less desirable situation than he was in before his connexion with us... At present, I can only conjecture that his greatest danger will arise from the very impolitic declarations of his antipathy to the ihhabitants of Bolabola; for these people, from a principle of jealousy, will, no doubt, endeavour to render him obnoxious to those of Huaheine; as they are at peace with that island at present, and may easily effect their designs, many of them living there. This is a circumstance which, of all others, he might the most easily have avoided; for they were not only free from any aversion to him, but the person whom we found at Tiaraboo as an ambassador, absolutely offered to reinstate him in the property that was formerly his father's. But he refused this peremptorily; and, to the very last, continued determined to take the first opportunity that offered of satisfying his revenge in battle. To this, I guess, he is not a little spurred by the coat of mail he brought from England; clothed in which, and in possession of some fire-arms, he fancies that he shall be invincible.

Whatever faults belonged to Omai's character, they were more than over-balanced by his great good nature and docile disposition. During the whole time he was with me, I very seldom had reason to be seriously displeased with his general conduct. His grateful heart always retained the highest sense of the favours he had received in England; nor will he ever forget those who honoured him with their protection and friendship during his stay there. He had a tolerable share of understanding, but wanted application and perseverance to exert it; so that his knowledge of things was very general, and, in many instances, imperfect. He was not a man of much observation. There were many useful arts, as well as elegant amusements, amongst the people of the Friendly Islands, which he might have conveyed to his own, where they probably would have been readily adopted, as being so much in their own way. But I never found that he used the least endeavour to make himself master of any one. This kind of indifference is, indeed, the characteristic foible of his nation. Europeans have visited them, at times, for these ten years past; yet we could not discover the slightest trace of any attempt to profit by this intercourse; nor have they hitherto copied after us in any one thing. We are not, therefore, to expect that Omai will be able to introduce many of our arts and customs among them, or that he will endeavour to bring to perfection the various fruits and vegetables we planted, which will be no small acquisition. But the greatest benefit these islands are likely to receive from Omai's travels will be in the animals that have been left upon them, which, probably, they never would have got had he not come to England. When these multiply, of which I think there is little doubt, Otaheite and the Society Islands will equal, if not exceed, any place in the known world for provisions.

Omai's return, and the substantial proofs he brought back with him of our liberality, encouraged many to offer themselves as volunteers to attend me to Pretane. I took every opportunity of expressing my determination to reject all such applications. But, notwithstanding this, Omai, who was very ambitious of remaining the only great traveller, being afraid lest I might be prevailed upon to put others in a situation of rivalling him, frequently put me in mind, that Lord Sandwich had told him no others of his countrymen were to come to England.

If there had been the most distant probability of any ship being again sent to New Zealand, I would have brought the two youths of that country home with me, as both of them were very desirous of continuing with us. Tiarooa, the eldest, was an exceedingly well-disposed young man, with strong natural sense, and capable of receiving any instruction. He seemed to be fully sensible of the inferiority of his own country to these islands, and resigned himself, though perhaps with reluctance, to end his days in ease and plenty in Huaheine. But the other was so strongly attached to us, that he was taken out of the ship and carried ashore by force. He was a witty, smart boy; and on that account much noticed on board.

© 2000 Michael Dickinson