CJC:

About nine o'clock in the morning, Otoo, the king of the whole island, attended by a great number of canoes full of people, came from Oparre, his place of residence, and having landed on Matavai Point, sent a message on board, expressing his desire to see me there. Accordingly I landed, accompanied by Omai, and some of the officers. We found a prodigious number of people assembled on this occasion, and in the midst of them was the king, attended by his father, his two brothers, and three sisters. I went up first and saluted him, being followed by Omai, who kneeled and embraced his legs. He had prepared himself for this ceremony, by dressing himself in his very best suit of clothes, and behaved with a great deal of respect and modesty. Nevertheless, very little notice was taken of him. Perhaps envy had some share in producing this cold reception. He made the chief a present of a large piece of red feathers, and about two or three yards of gold cloth; and I gave him a suit of fine linen, a gold-laced hat, some tools, and, what was of more value than all the other articles, a quantity of red feathers, and one of the bonnets in use at the Friendly Islands.

After the hurry of this visit was over, the king and the whole royal family accompanied me on board, followed by several canoes, laden with all kind of provisions, in quantity sufficient to have served the companies of both ships for a week. Each of the family owned, or pretended to own, a part; so that I had a present from every one of them; and every one of them had a separate present in return from me; which was the great object in view. Soon after, the king's mother, who had not been present at the first interview, came on board, bringing with her a quantity of provisions and cloth, which she divided between me and Omai; for, although he was but little noticed at first by his countrymen, they no sooner gained the knowledge of his riches, than they began to court his friendship. I encouraged this as much as I could: for it was my wish to fix him with Otoo. As I intended to leave all my European animals at this island, I thought he would be able to give some instruction about the management of them, and about their use. Besides, I knew and saw, that the farther he was from his native island, he would be the better respected. But, unfortunately, poor Omai rejected my advice, and conducted himself in so imprudent a manner, that he soon lost the friendship of Otoo, and of every other person of note in Otaheite. He associated with none but vagabonds and strangers, whose sole views were to plunder him; and, if I had not interfered, they would not have left him a single article worth the carrying from the island. This necessarily drew upon him the ill-will of the principal chiefs; who found that they could not procure, from any one in the ships, such valuable presents as Omai bestowed on the lowest of the people, his companions.

As soon as we had dined, a party of us accompanied Otoo to Oparre, taking with us the poultry, with which we were to stock the island. They consisted of a peacock and hen (which Lord Besborough was so kind as to send me for this purpose a few days before I left London); a turkey-cock and hen; one gander, and three geese; a drake, and four ducks. All these I left at Oparre, in the possession of Otoo; and the geese and ducks began to breed, before we sailed. We found there, a gander, which the natives told us, was the same that Captain Wallis had given to Oberea ten years before; several goats; and the Spanish bull, whom they kept tied to a tree, near Otoo's house. I never saw a finer animal of his kind. He was now the property of Etary, and had been brought from Oheitepeha to this place, in order to be shipped for Bolabola. But it passes my comprehension, how they can contrive to carry him in one of their canoes. If we had not arrived, it would have been of little consequence who had the property of him, as, without a cow, he could be of no use; and none had been left with him. Though the natives told us that there were cows on board the Spanish ships, and that they took them away with them, I cannot believe this; and should rather suppose, that they had died in the passage from Lima. The next day, I sent the three cows, that I had on board, to this bull; and the bull, which I had brought, the horse and mare, and sheep, I put ashore at Matavai. Having thus disposed of these passengers, I found myself lightened of a very heavy burthen. The trouble and vexation that attended the bringing of this living cargo thus far, is hardly to be conceived. But the satisfaction that I felt, in having been so fortunate as to fulfil his Majesty's humane design, in sending such valuable animals, to supply the wants of two worthy nations, sufficiently recompensed me for the many anxious hours I had passed, before this subordinate object of my voyage could be carried into execution.¹

As I intended to make some stay here, we set up the two observatories on Matavai Point. Adjoining to them, two tents were pitched for the reception of a guard, and of such people as it might be necessary to leave on shore, in different departments. At this station, I intrusted the command to Mr. King; who, at the same time, attended the observations for ascertaining the going of the time-keeper, and other purposes. During our stay, various necessary operations employed the crews of both ships. The Discovery's main-mast was carried ashore, and made as good as ever. Our sails and water-casks were repaired; the ships were caulked; and the rigging all overhauled. We also inspected all the bread that we had on board in casks; and had the satisfaction to find, that but little of it was damaged.

On the 26th, I had a piece of ground cleared for a garden, and planted it with several articles; very few of which, I believe, the natives will ever look after. Some melons, potatoes, and two pine-apple plants, were in a fair way of succeeding, before we left the place. I had brought from the Friendly Islands several shaddock trees. These I also planted here; and they can hardly fail of success, unless their growth should be checked by the same premature curiosity, which destroyed a vine planted by the Spaniards at Oheitepeha. A number of the natives got together, to taste the first fruit it bore; but, as the grapes were still sour, they considered it as little better than poison, and it was unanimously determined to tread it under foot. In that state, Omai found it by chance, and was overjoyed at the discovery. For he had a full confidence that, if he had but grapes, he could easily make wine. Accordingly, he had several slips cut from off the tree, to carry away with him; and we pruned and put in order the remains of it. Probably, grown wise by Omai's instructions, they may now suffer the fruit to grow to perfection, and not pass so hasty a sentence upon it again.

We had not been eight-and-forty hours at anchor in Matavai Bay, before we were visited by our old friends. Not one of them came empty-handed; so that we had more provisions than we knew what to do with. What was still more, we were under no apprehensions of exhausting the island, which presented to our eyes every mark of the most exuberant plenty, in every article of refreshment.

Soon after our arrival here one of the natives, whom the Spaniards had carried with them to Lima, paid us a visit, but in his external appearance he was not distinguishable from the rest of his countrymen. However he had not forgot some Spanish words which he had acquired, though he pronounced them badly: amongst them the most frequent were si Sennor; and when a stranger was introduced to him he did not fail to rise up and accost him as well as he could. We also found here the young man whom we called Oedidee, but whose real name is Heete-heete. I had carried him from Ulietea in 1773, and brought him back in 1774, after he had visited the Friendly Islands, New Zealand, Easter Island and the Marqueses, and been on board my ship, in that extensive navigation, about seven months. He was at least as tenacious of his good-breeding as the man who had been at Lima; and "Yes, Sir", or "If you please, sir", was as frequently repeated by him as si Sennor was by the other. Heete-heete, who is a native of Bolabola, had arrived in Otaheite about three months before, with no other intention, that we could learn, than to gratify his curiosity, or, perhaps, some other favourite passion, which are very often the only object of the pursuit of other travelling gentlemen. It was evident, however, that he preferred the modes, and even garb, of his countrymen to ours; for, though I gave him some clothes, which our Admiralty Board had been pleased to send for his use (to which I added a chest of tools, and a few other articles, as a present from myself), he declined wearing them after a few days. This instance, and that of the person who had been at Lima, may be urged as a proof of the strong propensity natural to man of returning to habits acquired at an early age, and only interrupted by accident. And perhaps it may be concluded, that even Omai, who had imbibed almost the whole English manners, will, in a very short time after our leaving him, like Oedidee and the visitor of Lima, return to his own native garments.

In the morning of the 27th, a man came from Oheitepeha, and told us that two Spanish ships had anchored in that bay the night before, and, in confirmation of this intelligence, he produced a piece of coarse blue cloth, which he said he got out of one of the ships, and which, indeed, to appearance was almost quite new. He added, that Mateema was in one of the ships, and that they were to come down to Matavai in a day or two. Some other circumstances which he mentioned, with the foregoing ones, gave the story so much the air of truth, that I despatched Lieutenant Williamson, in a boat, to look into Oheitepeha Bay; and, in the mean time, I put the ships into a proper posture of defence: for, though England and Spain were in peace when I left Europe, for aught I knew, a different scene might, by this time, have opened. However, on farther inquiry, we had reason to think that the fellow who brought the intelligence had imposed upon us; and this was put beyond all doubt when Mr. Williamson returned next day, who made his report to me that he had been at Oheitepeha, and found that no ships were there now, and that none had been there since we left it. The people of this part of the island where we now were, indeed, told us from the beginning that it was a fiction invented by those of Tiaraboo: but what view they could have we were at a loss to conceive, unless they supposed that the report would have some effect in making us quit the island, and by that means deprive the people of Otaheite-nooe of the advantages they might reap from our ships continuing there, the inhabitants of the two parts of the island being inveterate enemies to each other.

From the time of our arrival at Matavai the weather had been very unsettled, with more or less rain every day, till the 29th, before which we were not able to get equal altitudes of the sun for ascertaining the going of the time-keeper. The same cause also retarded the caulking, and other necessary repairs of the ships. In the evening of this day the natives made a precipitate retreat, both from on board the ships and from our station on shore: for what reason we could not at first learn; though, in general, we guessed it arose from their knowing that some theft had been committed, and apprehending punishment on that account. At length I understood what had happened. One of the surgeon's mates had been in the country to purchase curiosities, and had taken with him four hatchets for that purpose. Having employed one of the natives to carry them for him, the fellow took an opportunity to run off with so valuable a prize. This was the cause of the sudden flight, in which Otoo himself and his whole family had joined; and it was with difficulty that I stopped them, after following them two or three miles. As I had resolved to take no measures for the recovery of the hatchets, in order to put my people upon their guard against such negligence for the future, I found no difficulty in bringing the natives back, and in restoring everything to its usual tranquillity.

Hitherto the attention of Otoo and his people had been confined to us; but, the next morning, a new scene of business opened, by the arrival of some messengers from Eimeo, or (as it is much oftener called by the natives) Morea, with intelligence that the people in that island were in arms; and that Otoo's partisans there had been worsted, and obliged to retreat to the mountains. The quarrel between the two islands, which commenced in 1774, had, it seems, partly subsisted ever since. The formidable armament which I saw at that time, had sailed soon after I then left Otaheite; but the malcontents of Eimeo had made so stout a resistance, that the fleet had returned without effecting much; and now another expedition was necessary.

On the arrival of these messengers all the chiefs, who happened to be at Matavai, assembled at Otoo's house, where I actually was at the time, and had the honour to be admitted into their council. One of the messengers opened the business of the assembly in a speech of considerable length: but I understood little of it, besides its general purport, which was to explain the situation of affairs in Eimeo, and to excite the assembled chiefs of Otaheite to arm on the occasion. This opinion was combated by others, who were against commencing hostilities; and the debate was carried on with great order, no more than one man speaking at a time. At last they became very noisy, and I expected that our meeting would have ended like a Polish diet. But the contending great men cooled as fast as they grew warm, and order was soon restored. At length, the party for war prevailed; and it was determined that a strong force should be sent to assist their friends in Eimeo; but this resolution was far from being unanimous. Otoo, during the whole debate, remained silent, except that, now and then, he addressed a word or two to the speakers. Those of the council who were for prosecuting the war applied to me for my assistance; and all of them wanted to know what part I would take. Omai was sent for to be my interpreter; but, as he could not be found, I was obliged to speak for myself, and told them, as well as I could, that as I was not thoroughly acquainted with the dispute, and as the people of Eimeo had never offended me, I could not think myself at liberty to engage in hostilities against them. With this declaration they either were, or seemed satisfied.

On our inquiring into the cause of the war, we were told that some years ago a brother of Waheadooa, of Tieraboo, was sent to Eimeo, at the request of Maheine, a popular chief of that island, to be their king; but that he had not been there a week before Maheine, having caused him to be killed, set up for himself, in opposition to Tierataboonooe, his sister's son, who became the lawful heir; or else had been pitched upon by the people of Otaheite, to succeed to the government on the death of the other.

Towha, who is a relation of Otoo, and chief of the district of Tettaha, a man of much weight in the island, and who had been commander-in-chief of the armament fitted out against Eimeo in 1774, happened not to be at Matavai at this time, and, consequently, was not present at any of these consultations. It however appeared that he was no stranger to what was transacted, and that he entered with more spirit into the affair than any other chief; for, early in the morning of the first of September, a messenger arrived from him to acquaint Otoo that he had killed a man, to be sacrificed to Eatooa, to implore the assistance of the god against Eimeo. This act of worship was to be performed at the great morai at Attahooroo; and Otoo's presence, it seems, was absolutely necessary on that solemn occasion.

That the offering of human sacrifices is part of the religious institutions of this island, had been mentioned by Mons. Bougainville, on the authority of the native whom he carried with him to France. During my last visit to Otaheite, and while I had opportunities of conversing with Omai on the subject, I had satisfied myself that there was too much reason to admit that such a practice, however inconsistent with the general humanity of the people, was here adopted. But, as this was one of those extraordinary facts, about which many are apt to retain doubts, unless the relater himself has had ocular proof to confirm what he had heard from others, I thought this a good opportunity of obtaining the highest evidence of its certainty, by being present myself at the solemnity; and accordingly proposed to Otoo that I might be allowed to accompany him. To this he readily consented; and we immediately set out in my boat, with my old friend Potatou, Mr. Anderson, and Mr. Webber, Omai following in a canoe. In our way we landed upon a little island, which lies off Tettaha, where we found Towha and his retinue. After some little conversation between the two chiefs on the subject of the war, Towha addressed himself to me, asking my assistance. When I excused myself he seemed angry, thinking it strange that I, who had always declared myself to be the friend of their island, would not now go and fight against its enemies. Before we parted he gave to Otoo two or three red feathers, tied up in a tuft; and a lean, half-starved dog was put into a canoe that was to accompany us. We then embarked again, taking on board a priest, who was to assist at the solemnity.

As soon as we landed at Attahooroo, which was about two o'clock in the afternoon, Otoo expressed his desire that the seamen might be ordered to remain in the boat; and that Mr. Anderson, Mr. Webber, and myself might take off our hats as soon as we should come to the morai, to which we immediately proceeded, attended by a great many men and some boys, but not one woman. We found four priests and their attendants, or assistants, waiting for us. The dead body, or sacrifice, was in a small canoe that lay on the beach, and partly in the wash of the sea, fronting the morai. Our company stopped about twenty or thirty paces from the priests. Here Otoo placed himself, we and a few others standing by him, while the bulk of the people remained at a greater distance.

The ceremonies now began... In the course of this, some hair was pulled off the head of the sacrifice, and the left eye taken out, both of which were presented to Otoo wrapped up in a green leaf. He did not, however, touch it; but gave to the man who presented it the tuft of feathers which he had received from Towha: this, with the hair and eye, was carried back to the priests. Soon after Otoo sent to them another piece of feathers, which he had given me in the morning to keep in my pocket. During some part of the last ceremony, a kingfisher made a noise in the trees. Otoo turned to me, saying, "That is the Eatooa!" and seemed to look upon it to be a good omen.

The body was then carried a little way with its head toward the morai, and laid under a tree, near which were fixed three broad thin pieces of wood, differently but rudely carved. Bundles of cloth were laid on a part of the morai, and the tufts of red feathers were placed at the feet of the sacrifice, round which the priests took their stations; and we were now allowed to go as near as we pleased. He who seemed to be the chief priest sat at a small distance, and spoke for a quarter of an hour, but with different tones and gestures, so that he seemed often to expostulate with the dead person, to whom he constantly addressed himself; and sometimes asked several questions, seemingly with respect to the propriety of his having been killed. At other times he made several demands, as if the deceased either now had power himself, or interest with the divinity, to engage him to comply with such requests. Amongst which, we understood, he asked him to deliver Eimeo, Maheine its chief, the hogs, women, and other things of the island, into their hands; which was, indeed, the express intention of the sacrifice. He then chanted a prayer, which lasted half an hour, in a whining, melancholy tone, accompanied by two other priests, and in which Potatou and some others joined. In the course of this prayer some more hair was plucked by a priest from the head of the corpse, and put upon one of the bundles. After this the chief priest prayed alone, holding in his hand the feathers which came from Towha. When he had finished he gave them to another, who prayed in like manner. Then all the tufts of feathers were laid upon the bundles of cloth, which closed the ceremony at this place.

The corpse was then carried up to the most conspicuous part of the morai, with the feathers, the two bundles of cloth, and the drums; the last of which beat slowly. The feathers and bundles were laid against the pile of stones, and the corpse at the foot of them. The priests having again seated themselves round it, renewed their prayers; while some of the attendants dug a hole about two feet deep, into which they threw the unhappy victim, and covered it with earth and stones. While they were putting him into the grave, a boy squeaked aloud, and Omai said to me, that it was the Eatooa. During this time, a fire having been made, the dog before mentioned was produced and killed, by twisting his neck and suffocating him. The hair was singed off, and the entrails taken out and thrown into the fire, where they were left to consume. But the heart, liver, and kidneys were only roasted, by being laid on the stones for a few minutes; and the body of the dog, after being besmeared with the blood which had been collected in a cocoa-nut shell, and dried over the fire, was, with the liver, &c., carried and laid down before the priests, who sat praying round the grave. They continued their ejaculations over the dog for some time, while two men, at intervals, beat on two drums very loud; and a boy screamed as before, in a loud shrill voice, three different times. This, as we were told, was to invite the Eatooa to feast on the banquet that they had prepared for him. As soon as the priests had ended their prayers, the carcase of the dog, with what belonged to it, were laid on a whatta, or scaffold, about six feet high, that stood close by, on which lay the remains of two other dogs, and of two pigs which had lately been sacrificed, and at this time emitted an intolerable stench. This kept us at a greater distance than would otherwise have been required of us. For after the victim was removed from the sea-side toward the morai, we were allowed to approach as near as we pleased. Indeed, after that, neither seriousness nor attention were much observed by the spectators. When the dog was put upon the whatta, the priests and attendants gave a kind of shout, which closed the ceremonies for the present. The day being now also closed, we were conducted to a house belonging to Potatou, where we were entertained and lodged for the night.

Some other religious rites were performed next day, but on this subject we think we have said enough to satisfy our readers - perhaps to disgust them. However, for anyone who is curious about the significance of the bundles of cloth which were placed on the morai, one of them was opened and it contained the maro, or badge of kings; an ornamented banner which was used as a symbol of authority, just like European ensigns (or flags) of royalty. The other was supposed to contain the god Ooro within an ark-like coffer.

CJC: The unhappy victim offered to the object of their worship upon this occasion seemed to be a middle-aged man, and, as we were told, was a towtow, that is, one of the lowest class of the people. But, after all my inquiries, I could not learn that he had been pitched upon on account of any particular crime committed by him meriting death. It is certain, however, that they generally make choice of such guilty persons for their sacrifice, or else of common low fellows, who stroll about from place to place and from island to island, without having any fixed abode, or any visible way of getting an honest livelihood, of which description of men enough are to be met with at these islands. Having had an opportunity of examining the appearance of the body of the poor sufferer now offered up, I could observe that it was bloody about the head and face, and a good deal bruised upon the right temple; which marked the manner of his being killed. And we were told, that he had been privately knocked on the head with a stone.

Those who are devoted to suffer, in order to perform this bloody act of worship, are never apprised of their fate till the blow is given that puts an end to their existence. Whenever any one of the great chiefs thinks a human sacrifice necessary on any particular emergency, he pitches upon the victim. Some of his trusty servants are then sent, who fall upon him suddenly, and put him to death with a club or by stoning him. The king is next acquainted with it, whose presence at the solemn rites that follow is, as I was told, absolutely necessary; and, indeed, on the present occasion, we could observe that Otoo bore a principal part. The solemnity itself is called Poore Eree, or chief's prayer; and the victim who is offered up Taata-taboo, or consecrated man. This is the only instance where we have heard the word taboo used at this island, where it seems to have the same mysterious signification as at Tonga, though it is there applied to all cases where things are not to be touched. But at Otaheite, the word raa serves the same purpose, and is full as extensive in its meaning.

It is much to be regretted that a practice so horrid in its own nature and so destructive of that inviolable right of self-preservation which every one is born with, should be found still existing; and (such is the power of superstition to counteract the first principles of humanity!) existing amongst a people in many other respects emerged from the brutal manners of savage life. What is still worse, it is probable that these bloody rites of worship are prevalent throughout all the wide-extended islands of the Pacific Ocean. The similarity of customs and language, which our late voyages have enabled us to trace between the most distant of these islands, makes it not unlikely that some of the most important articles of their religious institutions should agree. And, indeed, we have the most authentic information that human sacrifices continue to be offered at the Friendly Islands. On the approaching sequel of the Natche festival at Tonge-taboo, we had been told that ten men were to be sacrificed. This may give us an idea of the extent of this religious massacre in that island. And though we should suppose that never more than one person is sacrificed, on any single occasion, at Otaheite, it is more than probable that these occasions happen so frequently as to make a shocking waste of the human race; for I counted no less than forty-nine skulls of former victims lying before the morai, where we saw one more added to the number. And as none of those skulls had as yet suffered any considerable change from the weather, it may hence be inferred, that no great length of time had elapsed since, at least, this considerable number of unhappy wretches had been offered upon this altar of blood.

On being asked what the intention of it was? the natives said that it was an old custom, and was agreeable to their god, who delighted in, or, in other words, came and fed upon the sacrifices; in consequence of which he complied with their petitions. Upon its being objected that he could not feed on these, as he was neither seen to do it, nor were the bodies of the animals quickly consumed; and that, as to the human victim, they prevented his feeding on him by burying him. But to all this they answered, that he came in the night, but invisibly, and fed only on the soul or immaterial part, which, according to their doctrine, remains about the place of sacrifice, until the body of the victim be entirely wasted by putrefaction.

The close of the very singular scene exhibited at the morai, leaving us no other business in Attahooroo, we embarked about noon, in order to return to Matavai; and, in our way, visited Towha, who had remained on the little island, where we met him the day before. Some conversation passed between Otoo and him, on the present posture of public affairs; and then the latter solicited me, once more, to join them in their war against Eimeo. By my positive refusal I entirely lost the good graces of this chief. Before we parted, he asked us if the solemnity at which we had been present, answered our expectations; what opinion we had of its efficacy; and whether we performed such acts of worship in our own country? During the celebration of the horrid ceremony, we had preserved a profound silence; but, as soon as it was closed, had made no scruple in expressing our sentiments very freely about it to Otoo and those who attended him; of course, therefore, I did not conceal my detestation of it in this conversation with Towha. Besides the cruelty of the bloody custom, I strongly urged the unreasonableness of it; telling the chief that such a sacrifice, far from making the Eatooa propitious to their nation, as they ignorantly believed, would be the means of drawing down his vengeance; and that, from this very circumstance, I took upon me to judge that their intended expedition against Maheine would be unsuccessful. This was venturing pretty far upon conjecture, but still I thought that there was little danger of being mistaken. For I found that there were three parties in the island, with regard to this war; one extremely violent for it, another perfectly indifferent about the matter, and the third openly declaring themselves friends to Maheine and his cause. Under these circumstances of disunion distracting their councils, it was not likely that such a plan of military operations would be settled as could insure even a probability of success. In conveying our sentiments to Towha on the subject of the late sacrifice, Omai was made use of as our interpreter; and he entered into our arguments with so much spirit that the chief seemed to be in great wrath; especially when he was told that if he had put a man to death in England, as he had done here, his rank would not have protected him from being hanged for it. Upon this he exclaimed, Maeno! maeno! [vile! vile!] and would not hear another word. During this debate many of the natives were present, chiefly the attendants and servants of Towha himself; and when Omai began to explain the punishment that would be inflicted in England upon the greatest man if he killed the meanest servant, they seemed to listen with great attention, and were, probably, of a different opinion from that of their master on this subject.

After leaving Towha we proceeded to Oparre, where Otoo pressed us to spend the night. We landed in the evening; and on our road to his house had an opportunity of observing in what manner these people amuse themselves, in their private heevas. About a hundred of them were found sitting in a house; and in the midst of them were two women, with an old man behind each of them, beating very gently upon a drum; and the women, at intervals singing in a softer manner than I ever heard at their other diversions. The assembly listened with great attention, and were seemingly almost absorbed in the pleasure the music gave them; for few took any notice of us, and the performers never once stopped. It was almost dark before we reached Otoo's house, where we were entertained with one of their public heevas, or plays, in which his three sisters appeared as the principal characters. This was what they call a heeva raä, which is of such a nature that nobody is to enter the house or area where it is exhibited. When the royal sisters are the performers this is always the case. Their dress on this occasion was truly picturesque and elegant; and they acquitted themselves in their parts in a very distinguished manner; though some comic interlude, performed by four men, seemed to yield greater pleasure to the audience, which was numerous. The next morning we proceeded to Matavai, leaving Otoo at Oparre; but his mother, sisters, and several other women, attended me on board, and Otoo himself followed me soon after.

While Otoo and I were absent from the ships they had been sparingly supplied with fruit, and had few visitors. After our return we again overflowed with provisions and with company. On the 4th a party of us dined ashore with Omai, who gave excellent fare, consisting of fish, fowls, pork, and puddings. After dinner I attended Otoo, who had been one of the party, back to his house, where I found all his servants very busy getting a quantity of provisions ready for me. Amongst other articles there was a large hog, which they killed in my presence. There was also a large pudding, the whole process in making which I saw. It was composed of bread-fruit, ripe plantains, taro, and palm or pandanus nuts, each rasped, scraped, or beat up fine, and baked by itself. A quantity of juice, expressed from cocoa-nut kernels, was put into a large tray, or wooden vessel. The other articles, hot from the oven, were deposited in this vessel; and a few hot stones were also put in, to make the contents simmer. Three or four men made use of sticks to stir the several ingredients, till they were incorporated one with another, and the juice of the cocoa-nut was turned to oil; so that the whole mass, at last, became of the consistency of a hasty-pudding. Some of these puddings are excellent, and few that we make in England equal them. I seldom or never dined without one when I could get it, which was not always the case. Otoo's hog being baked, and the pudding which I have described, being made, they, together with two living hogs, and a quantity of bread-fruit and cocoa-nuts, were put into a canoe, and sent on board my ship, followed by myself and all the royal family.

The following evening, a young ram of the Cape breed, that had been lambed, and, with great care, brought up on board the ship, was killed by a dog. Incidents are of more or less consequence, as connected with situation. In our present situation, desirous as I was to propagate this useful race amongst these islands, the loss of the ram was a serious misfortune; as it was the only one I had of that breed; and I had only one of the English breed left. In the evening of the 7th, we played off some fire-works before a great concourse of people. Some were highly entertained with the exhibition; but by far the greater number of spectators were terribly frightened; insomuch that it was with difficulty we could prevail upon them to keep together to see the end of the show. A table-rocket was the last. It flew off the table, and dispersed the whole crowd in a moment; even the most resolute among them fled with precipitation.

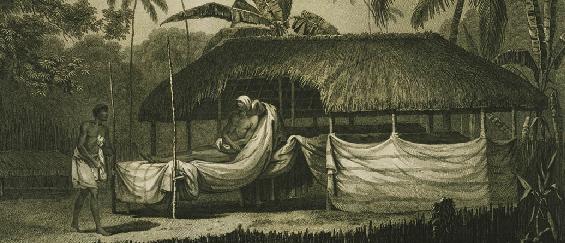

Otoo was not more attentive to supply our wants, by a succession of presents, than he was to contribute to our amusement, by a succession of diversions. A party of us having gone down to Oparre, on the 10th, he treated us with what may be called a play. His three sisters were the actresses; and the dresses they appeared in were new and elegant; that is, more so than we had usually met with at any of these islands. But the principal object I had in view, this day, in going to Oparre, was to take a view of an embalmed corpse, which some of our gentlemen had happened to meet with at that place, near the residence of Otoo. On inquiry, I found it to be the remains of Tee, a chief well known to me, when I was at this Island, during my last voyage. We found the body not only entire in every part; but, what surprised us much more, was, that putrefaction seemed scarcely to be begun, as there was not the least disagreeable smell proceeding from it, though the climate is one of the hottest, and Tee had been dead above four months. The only remarkable alteration that had happened, was a shrinking of the muscular parts of the eyes; but the hair and nails were in their original state, and still adhered firmly; and the several joints were quite pliable, or in that kind of relaxed state which happens to persons who faint suddenly. Such were Mr. Anderson's remarks to me, who also told me, that, on his inquiring into the method of effecting this preservation of their dead bodies, he had been informed that soon after their death, they are disembowelled, by drawing the intestines, and other viscera, out at the anus; and the whole cavity is then filled or stuffed with cloth, introduced through the same part; that when any moisture appeared on the skin, it was carefully dried up, and the bodies afterward rubbed all over with a large quantity of perfumed cocoa-nut oil; which, being frequently repeated, preserved them a great many months; but that, at last, they gradually moulder away. This was the information Mr. Anderson received; for my own part, I could not learn any more about their mode of operation than what Omai told me, who said, that they made use of the juice of a plant which grows amongst the mountains; of cocoa-nut oil; and of frequent washing with sea water. I was also told that the bodies of all their great men, who died a natural death, are preserved in this manner; and that they expose them to public view for a considerable time after. At first, they are laid out every day, when it does not rain; afterward, the intervals become greater and greater; and, at last, they are seldom to be seen.

On the 13th, Captain Clerke and I, mounted on horseback, took a ride round the plain of Matavai, to the very great surprise of a great train of people who attended on the occasion, gazing upon us with as much astonishment as if we had been centaurs. Omai, indeed, had, once or twice before this, attempted to get on horseback; but he had as often been thrown off, before he could contrive to seat himself; so that this was the first time they had seen anybody ride a horse. What Captain Clerke and I began, was, after this, repeated every day, while we staid, by one or another of our people; and yet the curiosity of the natives continued still unabated. They were exceedingly delighted with these animals, after they had seen the use that was made of them; and, as far as I could judge, they conveyed to them a better idea of the greatness of other nations than all the other novelties put together that their European visitors had carried amongst them. Both the horse and mare were in good case, and looked extremely well.

The next day, Etary, or Olla, the god of Bolabola, who had, for several days past, been in the neighbourhood of Matavai, removed to Oparre, attended by several sailing canoes. We were told, that Otoo did not approve of his being so near our station, where his people could more easily invade our property. I must do Otoo the justice to say, that he took every method prudence could suggest to prevent thefts and robberies; and it was more owing to his regulations than to our circumspection that so few were committed. He had taken care to erect a little house or two on the other side of the river, behind our post, and two others close to our tents, on the bank between the river and the sea. In all these places some of his own people constantly kept watch; and his father generally resided on Matavai point; so that we were, in a manner, surrounded by them. Thus stationed, they not only guarded us in the night from thieves, but could observe everything that passed in the day; and were ready to collect contributions from such girls as had private connexions with our people, which was generally done every morning. So that the measures adopted by him to secure our safety, at the same time served the more essential purpose of enlarging his own profits.

In the morning of the 18th, Mr. Anderson, myself, and Omai went again with Otoo to Oparre, and took with us the sheep which I intended to leave upon the island, consisting of an English ram and ewe, and three Cape ewes, all which I gave to Otoo.

After dining with Otoo we returned to Matavai, leaving him at Oparre. This day and also the 19th we were very sparingly supplied with fruit. Otoo hearing of this, he and his brother, who had attached himself to Captain Clerke, came from Oparre between nine and ten o'clock in the evening with a large supply for both ships. This marked his humane attention more strongly than anything he had hitherto done for us. The next day all the royal family came with presents, so that our wants were not only relieved, but we had more provisions than we could consume. Having got all our water on board, the ships being caulked, the rigging overhauled, and everything put in order, I began to think of leaving the island, that I might have sufficient time to spare for visiting others in this neighbourhood. With this view we removed from the shore our observatories and instruments, and bent the sails. Early the next morning Otoo came on board to acquaint me that all the war canoes of Matavai, and of the three other districts adjoining, were going to Oparre to join those belonging to that part of the island; and that there would be a general review there. Soon after, the squadron of Matavai was all in motion; and, after parading a while about the bay, assembled ashore near the middle of it. I now went in my boat to take a view of them.

Of those with stages on which they fight, or what they call their war-canoes, there were about sixty, with near as many more of a smaller size. I was ready to have attended them to Oparre; but, soon after, a resolution was taken by the chiefs that they should not move till the next day. I looked upon this to be a fortunate delay, as it afforded me a good opportunity to get some insight into their manner of fighting. With this view, I expressed my wish to Otoo that he would order some of them to go through the necessary manœuvres. Two were, accordingly ordered out into the bay, in one of which Otoo, Mr. King, and myself were embarked, and Omai went on board the other. When we had got sufficient sea-room, we faced and advanced upon each other, and retreated by turns, as quick as our rowers could paddle. During this, the warriors on the stages flourished their weapons, and played a hundred antic tricks, which could answer no other end, in my judgment, than to work up their passions and prepare them for fighting. Otoo stood by the side of our stage, and gave the necessary orders when to advance and when to retreat. In this, great judgment and a quick eye combined together seemed requisite to seize every advantage that might offer, and to avoid giving any advantage to the adversary. At last, after advancing and retreating from each other at least a dozen times, the two canoes closed head to head, or stage to stage; and after a short conflict, the troops on our stage were supposed to be all killed, and we were boarded by Omai and his associates. At that very instant, Otoo and all our paddlers leaped overboard, as if reduced to the necessity of endeavouring to save their lives by swimming.

If Omai's information is to be depended upon, their naval engagements are not always conducted in this manner. He told me, that they sometimes begin with lashing the two vessels together, head to head, and then fight till all the warriors are killed on one side or the other. But this close combat, I apprehend, is never practised but when they are determined to conquer or die. Indeed, one or the other must happen; for all agree that they never give quarter, unless it be to reserve their prisoners for a more cruel death the next day. The power and strength of these islands lie entirely in their navies. I never heard of a general engagement on land; and all of their decisive battles are fought on the water. If the time and place of conflict are fixed upon by both parties, the preceding day and night are spent in diversions and feasting. Toward morning they launch the canoes, put everything in order, and with the day begin the battle, the fate of which generally decides the dispute. The vanquished save themselves by a precipitate flight; and such as reach the shore fly with their friends to the mountains; for the victors, while their fury lasts, spare neither the aged, women, nor children. The next day they assemble at the morai, to return thanks to the Eatooa for the victory, and to offer up the slain as sacrifices, and the prisoners also, if they have any. After this, a treaty is set on foot, and the conquerors for the most part obtain their own terms, by which particular districts of lands, and sometimes whole islands, change their owners. Omai told us that he was once taken a prisoner by the men of BolaBola, and carried to that island, where he and some others would have been put to death the next day if they had not found means to escape in the night.

As soon as this mock fight was over, Omai put on his suit of armour, mounted a stage in one of the canoes, and was paddled all along the shore of the bay; so that every one had a full view of him. His coat of mail did not draw the attention of his countrymen so much as might have been expected. Some of them, indeed, had seen a part of it before; and there were others, again, who had taken such a dislike to Omai, from his imprudent conduct at this place, that they would hardly look at anything, however singular, that was exhibited by him.

© 2000 Michael Dickinson