The 'Earl Of Pembroke' leaving Whitby Harbor.

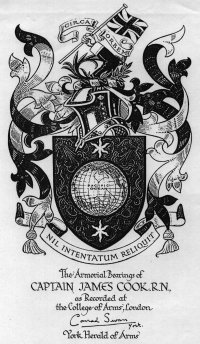

The Coat Of Arms (left) belongs to my ancestor: Captain James Cook, the Navigator. It was awarded posthumously by the King of England and is the only one ever to include a globe (centered on the Pacific Ocean) and Polar stars. The motto reads: "He left nothing unattempted". I am personally linked to him through my mother's side of the family, as one of her ancestor's married his sister Margaret. This union caused him to become my Great, Great, Great, Great Uncle.

The Coat Of Arms (left) belongs to my ancestor: Captain James Cook, the Navigator. It was awarded posthumously by the King of England and is the only one ever to include a globe (centered on the Pacific Ocean) and Polar stars. The motto reads: "He left nothing unattempted". I am personally linked to him through my mother's side of the family, as one of her ancestor's married his sister Margaret. This union caused him to become my Great, Great, Great, Great Uncle.

For those not familiar with the Captain, he first came to the attention of the British Admiralty during the conflicts with France for the possession of Canada. His Highly detailed charts of Canadian rivers and coastlines helped the British Fleet to launch successful Attacks on several French Strongholds and ultimately win the war there.

Later, he was selected to command several long expeditions to search for the rumored "Northwest Passage", observe the transit of Venus (from Tahiti) and to search for the "Great Southern Continent", which scientists in those days believed must exist in order to "Balance the Earth"! Along the way, he added a large number of new places to the World Map, including the Islands of Hawaii, which he was the first European to discover.

His remarkable voyages of exploration came to an abrupt end when, due to an unfortunate misunderstanding with his former Hosts, he was killed trying to prevent his men from firing at an angry crowd of Hawaiians. Later on, when tempers cooled, his remains were returned to his crew and he was buried at sea. A Naval Warship from Great Britain stops by each year to take care of his memorial near Kona on the 'Big Island' of Hawaii. The small white obelisk stands on one of the only two pieces of Sovereign Territory left in America¹.

Cook didn't find the fabled "Great Southland", but he discovered - in Australia - a country equally deserving of such a title! A piece of his original ship "The Endeavour", a converted coal-carrier, was taken into orbit aboard the Space-Shuttle of the same name.

The 'Earl Of Pembroke' leaving Whitby Harbor.

In fact, the humble collier was intended for a singularly adventurous role. She would carry a hand-picked group of naval officers and scientists to the farthest reaches of the Pacific to conduct vital astronomical studies and to make yet another search for the continent identified on the maps as Terra Australis Incognita. A collier had been selected because it could hold the large quantities of supplies and scientific equipment the voyagers would require, and also because it was flat-bottomed and was able to take the punishment of an accidental grounding.

On April 5 the Admiralty renamed the vessel Endeavour and ordered the Deptford carpenters to prepare her for the journey with the greatest dispatch. Within four weeks her hull had been sheathed with a second layer of planking to protect against tropical sea worms. Her masts and yards were scrapped for fresh-cut spars, and all her rigging was replaced with new hempen lines. On May 18 the ship was refloated and moored in the great Deptford Basin, alongside the mighty warships of the British Empire, to await the arrival of her commander.

To some Londoners the selection of Lieutenant James Cook as leader of the expedition to the Pacific was even more surprising than the Admiralty's choice of the Endeavour. At the age of 39, Cook was virtually unknown to his countrymen. In marked contrast to Commodore John Byron and Captain Samuel Wallis, the aristocratic leaders of England's earlier voyages of Pacific exploration, Cook sprang from the lower ranks of society, was haphazardly educated and had not even spent his whole career in the Royal Navy: His training had been in the merchant marine.

But, like the Endeavour, James Cook possessed exactly those qualities deemed crucial by the Admiralty for the success of the job at hand. For four years, beginning in 1763, Cook had sailed the rugged coast of Newfoundland, charting its bays and inlets with painstaking precision. More than once he had earned praise from the highest levels of the Navy for his surveying work and superb seamanship, and the Lords of the Admiralty reasoned that the talents that had been so valuable in the Newfoundland enterprise would be equally useful in the uncharted waters of the South Pacific. As it turned out, Cook would become the greatest explorer of his time - and the greatest Pacific explorer of all time.

As captain of the Endeavour, he would sight and survey hundreds of landfalls that no Westerner had ever laid eyes on. And though the Endeavour would never fire her guns at another ship in battle, Cook's epochal voyage aboard the converted collier was destined to bring under George III's sovereignty more land and wealth than any single naval victory of the powerful British fleet. But the most important prize of this and the two subsequent voyages that Cook would make was measured not in territory but in knowledge. Patient and methodical where his predecessors had been hasty and disorganized, he would sweep away myths and illusions on a prodigious scale, and in the end would give to the world a long-sought treasure: a comprehensive map of the Pacific.

Excerpt taken from the excellent study on Cook by Oliver E. Allen in TIME-LIFE books The Pacific Navigators © 1980

Portraits of Captain James Cook.

© 1996 Michael Dickinson

This page hosted by ![]() Get your own Free Home

Page

Get your own Free Home

Page