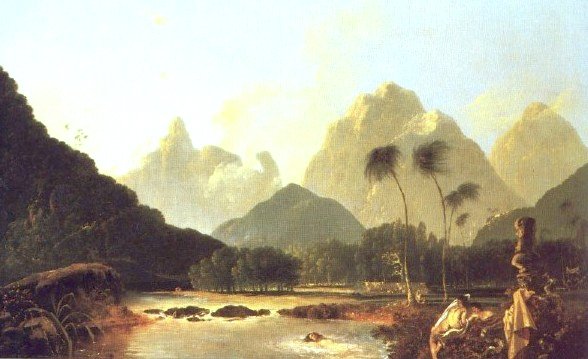

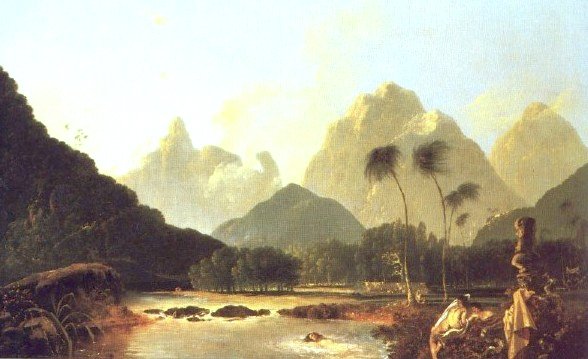

"Tahiti Revisited" by William Hodges

It fell to Captain James Cook to prove conclusively that long voyages and major discoveries were not incompatible. For his three great voyages, Cook chose little Whitby Colliers, with ample storage capacity for the provisions he knew he would need and with a shallow draught to enable him to explore unknown coastlines with greater safety in his search both for suitable anchorages and for edible greenstuffs. These included wild celery, scurvy-grass, winter's bark, purslaine, cresses, berries, and spruce leaves with which he brewed beer. Complemented by naturalists, artists and astronomers, Cook and his men spanned the oceans of the world.

In the words of Sir Hugh Palliser, Cook possessed, in an eminent degree, all the qualifications requisite for his profession and great undertakings; together with the amiable and worthy qualities of the best men. Cool and deliberate in judging; sagacious in determining; active in executing; steady and persevering in enterprising ... unsubdued by labour, difficulties and disappointments.

Cook's first voyage in HMS Endeavour from 1768-1771, was distinguished less by his health record than by his surveys and discoveries which added Australia and New Zealand to the British Crown. When the little collier finally completed her circumnavigation, 41 out of a ship's company of 94 had died, 31 from malaria and dysentery contracted at Batavia.

Cook learned the lesson, for his magnificent 60,000 mile circumnavigation of Antarctica from 1772-1775 was accomplished with the loss, in Resolution, of only one man from tuberculosis and three from accident. Three died in Adventure, one from scurvy and two from fever, but a boat's crew of eight men was murdered by Maoris. Nevertheless, there were at least five episodes of scurvy in Resolution though certainly less severe than the two outbreaks in Adventure. In fact, on both the first and second voyages, scurvy caused Cook to make unscheduled stops: on the first voyage at Suva, and on the second at Tahiti. Such was the consequence of relying upon MacBride's malt, rather than Lind's lemon juice as a general antiscorbutic. It was the only apparent departure from the principles which Dr James Lind had set out in his book Treatise on Scurvy which was published in 1757 and was a milestone in the improvement of health at sea.

It is important to bear in mind Palliser's appraisal of Cook's character when we consider Cook's remarkable personality change during his third voyage from 1776-1779 in search of a North West Passage. By the time he reached Nootka on Vancouver Island in 1778, his face had assumed an expression of almost constant severity, and Webber painted him when he had become morose and withdrawn.

During the second ice-edge search of the second voyage, in December 1773, Cook had developed loss of appetite, anaemia, vomiting, and constipation followed by acute intestinal obstruction from which he almost died. It was relieved spontaneously after seven days and the evidence appears to point to a heavy ascaris infestation. At Easter Island in April 1774, he had been adversely affected by sunlight which had caused darkening of the exposed skin and ulcerated lips in others, signs of aribionflavinosis. He evidently recovered in England between the second and third voyages when Nathaniel Dance painted his portrait, but had lost weight again, as John Webber's painting suggests, by the time he arrived at Queen Charlotte Sound, New Zealand, on the third voyage in February 1777.

The most likely explanation is that Cook suffered from a parasitic infestation of the intestine interfering with the absorption of thiamine and niacin, vitamins of the B group. Symptoms include prolonged ill health, fatigue, loss of appetite and weight, constipation or diarrhoea, digestive disturbances, loss of interest and initiative, irritability, depression, loss of concentration and memory, change of personality, and sometimes sensitivity to sunlight. They were all symptoms from which Cook suffered and which were attested by six independent observers, two of whom were his surgeons. There is absolutely no evidence that Cook ever suffered from venereal disease.

Indeed, had he made no other discovery but this, he would have been justly entitled to the recognition and gratitude of mankind.

© 1996 Michael Dickinson