|

The Stare Masters of Bangladesh .... by Adam (2004) _________________________________________________________________

What

suburban Canadian youth didn’t grow up dreaming of Bangladesh?

While thoughts of Paris turn to La Tour Eiffel, artists or

decadent nightlife, our fantasies of the Bangladeshi capital of Dhaka

conjure up…uh… well… Moslems… and… um… floods… and…

maybe pirated DVDs? Okay,

so as fantasy holidays go, it’s about as popular as an early-summer

colostomy. But the friendly Bangladeshi people recently treated me

to some colourful culture, lots of mucky curries and Thai

Airways recently started offering direct Chiang Mai - Chittagong

flights. As you can imagine the route is sort of the lima bean of air

routes – it lands on your travel plate only if someone else puts it

there. I went for work. I sat alone in the departure lounge of the sedate Chiang Mai airport hopeful that, as the solitary passenger, I would be able to remove my shirt for in-flight relaxation purposes. But 10 minutes before boarding, 50 short-fat Bangladeshis ruptured the stillness with an assault on the Duty Free shop. Chocolates and perfumes burrowed into their bulging plastic bags as they eyeballed the whiskey, which Bangladesh citizens are restricted from importing (being good Moslems, and all). They probably didn’t need chocolates either, judging by the Ralph Lauren-clad girth on display that day (Curiously, the majority – the impoverished, skinny Bangladeshis – don’t seem to fancy international travel.). But perfume - I thought - seemed advisable.

Yes,

it appeared that Bangladesh was to restore body odour as an arrow in my

quiver of complaints. After sniffing my way through the Thai populace

for five years now, I’ve found nary a smidgen of sharpness emanating

from these, the cleanest folk on our planet. Even Bangkok cab drivers

smell of butterscotch rose petals baked in a pie. Thai cultural practice

calls for 6-8 showers per day and frequent anointings with powder or

cream. But the poor Bangladeshis don’t seem to be endowed with such

sanitary alertness. My airplane row-mate corroborated this – the stink

of his groin following him out of the bathroom and lingering near

the overhead storage bins before sinking onto my lap, staining my

pant-leg. Bangladesh is the most crowded country in the world with 140 millions citizens huddled around a soppy landmass the size of Wisconsin. Once part of the newly minted nation of India, it was released to ‘freedom’ and became East Pakistan, the picked-on runt of the Pakistan family. After a bloody war with its big brother in the 70’s, Bangladesh declared sovereignty. Finally, Bangladeshis could enjoy famine, floods, strikes, coups and riots in peace. I

started in Chittagong, where I stayed at the always-cosy Al Faisal

Hotel. Here they dazzle you with 4-5 bill miscalculations before setting

any charge. As in most Bangladeshi hotels, the management encourage

staff to interrupt guests as often as possible. They knocked on my door

roughly eleven times in my first 24 hours – having me sign documents,

spritzing a haze of noxious disinfectant onto my belongings or shouting

broken English queries toward my air-conditioner. My

hosts in Chittagong were Fayas – the Moslem equivalent of a very

tall ewok – and his band of Rohingyan “journalists” for

which I was to deliver a media workshop. They were about the most

helpful people I’ve ever encountered. But there is a time when

helpfulness strays into maniacal oppression. That point arrived early

with my Rohingyan hosts. (Rohingyans are an oppressed Burmese ethnic

minority forced to flee to Bangladesh) As

in most Burmese cultures, they ensure your comfort by removing all

self-determination from your experience: forcing you to sit in spots

you’d rather avoid, pressing close against your body as you tramp

through crowded streets and imposing mysterious lumps of meat onto your

plate. During our first meal, I kept my dish fully loaded, assiduously

avoiding the hunk that resembled an infant’s hand, only to have Fayas

deliver it to the middle of my rice heap. We exchanged smiles and I

poked at the sides with my spoon, waiting for attention to shift

elsewhere. I was finally able to safely bury it under the refuse on the

bone disposal plate. After

our final day of unwavering companionship, I was ready to retreat to my

room and forgo any further helpful hosting. Our workshop ended at 4pm

and Mohammed popped out to run a quick errand for me. Three chillingly

long hours of forced small talk later, he returned and I was allowed

back to my hotel. Once out of their clutches, I changed into my standard

tropical wardrobe of underpants and eyeglasses, only to have my peace

shattered by a knock containing three Rohingyans wanting a seat on my

sofa. I let them in, saying “Hi…. uh…good to see you… how have

you all been for the last TWO WHOLE HOURS?” They

elbowed their ways across the room, hurled me into the lumpy chair I had

avoided for most of my stay, and sat primly on my bed and sofa. We

talked of refugees, democracy, etc. and they made The

next morning my hotel wake up call came a half hour early. Good thing

because there was Fayas at 615 to help me cap my toothpaste and collect

my socks. We rode a rickshaw to the station and he even boarded the

train, sitting with me until my seatmate scowled him into leaving. The

seven-hour ride from Chittagong to Dhaka was unsettling. Bangladesh was

suffering its worst floods in decades, with 2/3 of its land taken by the

rains. I was startled by the newspaper warning: “Tracks in Danger of

Snapping on Dhaka-Chittagong Rail.” We did indeed have to plough

through the swell, but we remained dry, unlike the soggy villagers

huddled on hilltop shelters. Life

near the rail tracks was forced onto skinny mounds of grass nudging

above the waters where villages and rice fields flourished only weeks

ago. Thousands died from diarrhea and waterborne diseases as the country

tried to drain itself. The floods destroyed millions of homes. Perhaps

it gives us perspective for our next foundation leak or mildew crisis. Luckily,

the Bangladeshi Prime Minister Kaleda Zia sprung into action after only

3 weeks of disaster. Her Mercedes limo delivered her to the banks of the

Dhaka swamp where she bestowed baggies of rice to the unwashed-overwashed

masses. She spent several nose-curling minutes sprinkling sustenance on

her people, managing to keep her delicately gloved fingers from actually

touching any of her dirty, dark citizens. Flash bulbs popped and

videotapes churned and she returned to her estate for a purging cucumber

facial. Bangladesh

is a great place to make lots of new, really aggressive friends. If you

enjoy a good face-shout from a stranger or settling disputes with a blow

to your challenger’s skull, Bangladesh is for you. As sedate as the

Thais are, the Bangladeshi are hostile. This

aggression is manifest in Bangladeshi traffic culture. In Thailand I can

veer into wrong lanes, crush tiny children or collide with market

stalls. The only punishment I receive from Thai drivers is a gentle

giggle and polite docility. But in Bdesh, traffic days burst with

relentless honking, irate threats and purposeful collisions. Drivers

will not relent when blocking each other’s paths. Stare-downs and

shouting matches persist for several minutes before the driver with

the more pressing errand surrenders. Some

foreigners on a bus were treated to a lesson in Bengali conflict

resolution after a stubborn truck held up their bus at a highway curve.

After several minutes of fruitless shouting, passengers emptied out of

the bus to beat and kick the offending truck driver. He was spared just

enough life to drag his bloody body into the cab and remove his truck

from the bus’ path. The passengers returned with satisfied smiles and

handshakes, as if they had just helped an elderly woman jump-start her

Mazda. Dhaka

is a spastic city of 10 million with the murky ventilation of a 1950’s

teachers’ lounge. Convoys of dented vehicles cough out fumes as burqa-clad

women, angry imams, colourfully festooned rickshaws, prim businessmen

and naked children mill about the mucky streets in search of ways to

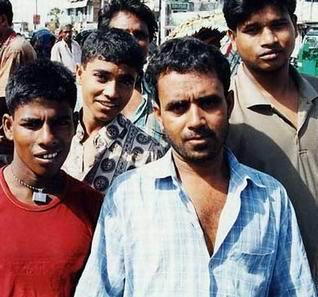

make a living. There is nary a tourist, so foreigners need to

acclimatize themselves to the relentless, creepy staring. There is a

different sense of privacy (i.e., you don’t get any) th My

Dhaka workshop (with another Burmese refugee group) was notable for our

swift ascent to the apex of workshop dullness. If synchronized yawning

ever becomes a medal sport, I know just who to coach. Participants

stared blankly at sheets while I spat out impatient questions and

eyeballed the clock. I tried in vain to boost the mood by injecting

interactive exercises like, “form small groups and discuss your

stupidity.” It

finally picked up towards the end after I implored a staff member to

take me to the streets to buy coffee. Even that was a challenge. We

spent 20-minutes rambling through hot alleyways, as I pleaded with my

host: “I see it… I see coffee…. No, really… it’s in that

shop…. Can we stop?… that shop has it too… I see it… where are

we going?” I

was ready to return to comparatively tame Thailand and embarked on my

long return journey the next day. Stuck in the Chittagong airport for 5

hours is not a gift for the vigorous traveller. There is nothing to do,

few comfy surfaces and little respite from the oppressive heat and

staring outside. Facing hunger, I was forced to purchase something

called a “mutton burger”. Normally I don’t eat cows or pigs, so I

wasn’t sure about my policy on mutton. Mutton comes from something

called a ‘lamb’, which I believe is in the chicken family, so I gave

it a try. It was a spicy little deal, made creepy by the occasional

crunchy bit. Lamb teeth, maybe? So

Bangladesh will probably remain one of the least visited nations on

earth. With the chronic floods, cyclones, general strikes and bombings,

there are myriad reasons to stay away. But if one does make it there,

they will find a certain charm in the chaos. Er… that’s what you

tell yourself, anyway.

This article appears in Farang Magazine, January 2005.

|

relentless, ominous staring. It was particularly generous of

them considering 2/3 of their country was underwater at the time.

relentless, ominous staring. It was particularly generous of

them considering 2/3 of their country was underwater at the time.  threats

about coming the next morning to help me get my 7 AM train. I tried to

laugh them off with “heh heh… no, really… you wouldn’t like me

in the morning… bad mood… heh… heh.” They nodded in accord and

finally made their exit.

threats

about coming the next morning to help me get my 7 AM train. I tried to

laugh them off with “heh heh… no, really… you wouldn’t like me

in the morning… bad mood… heh… heh.” They nodded in accord and

finally made their exit. at

allows locals to get involved with your business. Several times I

started street conversations only to lure crowds at the rate of

about 7 new onlookers per minute. One request for directions peaked

with approximately 40 men surrounding my rickshaw, staring at my camera.

at

allows locals to get involved with your business. Several times I

started street conversations only to lure crowds at the rate of

about 7 new onlookers per minute. One request for directions peaked

with approximately 40 men surrounding my rickshaw, staring at my camera.