Pampa de Chalviri, BOLIVIA

| Translate: EspaŮol - FranÁais - Deutsch - Italiano - PortuguÍs - Japanese - Korean - Chinese |

Pampa de Chalviri, BOLIVIA

| Translate: EspaŮol - FranÁais - Deutsch - Italiano - PortuguÍs - Japanese - Korean - Chinese |

NOVEMBER 28, 2000 -- Just as we left it, La Paz provided services that would satisfy at least one cultural craving; American fast food. We do the rounds, McDonalds, Burger King, McDonalds, Burger King, McDonalds, Burger King...

NOVEMBER 28, 2000 -- Just as we left it, La Paz provided services that would satisfy at least one cultural craving; American fast food. We do the rounds, McDonalds, Burger King, McDonalds, Burger King, McDonalds, Burger King...

NOVEMBER 30, 2000 -- 11 hours south from the capital by bus, takes us to the city of Potosi. At 4070 m.a.s.l., this city rates as the highest in the world with a population of about 110 000.

In 1545 the Spaniards discovered the mines of Potosi, thanks to information provided by one of the locals. This began the immediate exploitation and intensive mining for the seemingly inexhaustible quantities of silver the world has ever known. Mount Potosi or 'Cerro Rico', once an ancient volcano, overlooking the city at its foot, was bursting with so much silver it became transformed. When the Spaniards discovered the rich silver veins within the mountain, they tapped this new source in a way that had never been attempted under the Incas, exploiting the natives as slaves.

In 1545 the Spaniards discovered the mines of Potosi, thanks to information provided by one of the locals. This began the immediate exploitation and intensive mining for the seemingly inexhaustible quantities of silver the world has ever known. Mount Potosi or 'Cerro Rico', once an ancient volcano, overlooking the city at its foot, was bursting with so much silver it became transformed. When the Spaniards discovered the rich silver veins within the mountain, they tapped this new source in a way that had never been attempted under the Incas, exploiting the natives as slaves.

The 'minero', a person who stakes a claim of a seam could either work it directly or rent it out, though on condition that one fifth of the profits goes to the Spanish Crown. Work in the mines are carried out partly by forced labor and partly by free workers who were paid in kind, not in money. Under inhuman conditions and forced to work without a break, some die of exhaustion, if not by lack of air. Some seams were accessible only by children, used to crawl through cracks in the rock. Their parents sometimes resort to deform one of their legs at birth to spare them the obligation. Of the 10 or 12 children each Indian mother bore, only one or two survived. Indiscriminant use of mercury also played its part in the silver mining casualties.

For over 200 years since its discovery, the Spanish settlers of Potosi accumulated huge wealth; the city had become an urban center with 25 churches and establishments linked to the economic expansion of the West. By 1800, the silver levels began to taper off and so too, did the city's population. Towards the end of the 19th century a revival in Potosi occurred from the discovery of tin deep within. The fortunes rise again for the elite. That is, until the tin mines were nationalised in 1952. Tin production had dropped due to inefficent handling and increased depletion of the better deposits followed by the 1958 collapse of the international tin market to make matters worst for the average, struggling Bolivian miner.

DECEMBER 3, 2000 -- Mining still continues today in Cerro Rico, where the main yields are tin, zinc, lead, platinum and tungsten.

We decide to skip the tours of the mines altogether and instead, walk to the top of Cerro Rico for a day. Heading along a main city road in an eastward direction passing a few plazas, then cutting south toward the imposing hill crossing a river of nothing but thick grey effluent flowing through. It was like wandering through an industrial ghost town. Huge rusting steel parts

scatter the lower terrain, garbage everywhere, plastic bags riding the air currents above us. Despite all this, the surrounding land itself was strange

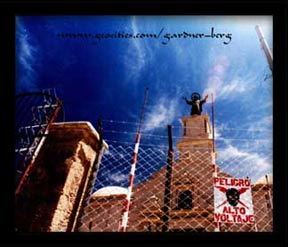

and beautiful, like a painting from the imagination of a depressed artist. It doesn't seem like many people climb the hill; (we only saw one person the whole day) but we hiked it to the top where a colonial church sits, overshadowing the

many marked graves around the western slope. The church seemed well-preserved; difficult to take seriously with the high barbed-wire fence enclosing it and the 'high voltage' signs placed at the entrance. But the views from here were just stupendous.

scatter the lower terrain, garbage everywhere, plastic bags riding the air currents above us. Despite all this, the surrounding land itself was strange

and beautiful, like a painting from the imagination of a depressed artist. It doesn't seem like many people climb the hill; (we only saw one person the whole day) but we hiked it to the top where a colonial church sits, overshadowing the

many marked graves around the western slope. The church seemed well-preserved; difficult to take seriously with the high barbed-wire fence enclosing it and the 'high voltage' signs placed at the entrance. But the views from here were just stupendous.

DECEMBER 4, 2000 -- We leave Potosi on a southbound bus to Uyuni (6 hours). We hook up with a wonderful couple from Austria and South Africa travelling in the same direction to sign up for tomorrow morning's tour of Salar de Uyuni, and the coloured lakes of the southern region (4 days, 3 nights). Our group of 6 included 2 more travellers (USA and Israel).

DECEMBER 4, 2000 -- We leave Potosi on a southbound bus to Uyuni (6 hours). We hook up with a wonderful couple from Austria and South Africa travelling in the same direction to sign up for tomorrow morning's tour of Salar de Uyuni, and the coloured lakes of the southern region (4 days, 3 nights). Our group of 6 included 2 more travellers (USA and Israel).

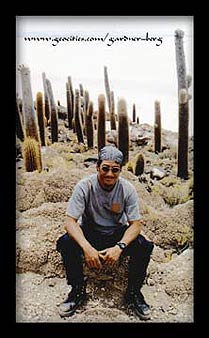

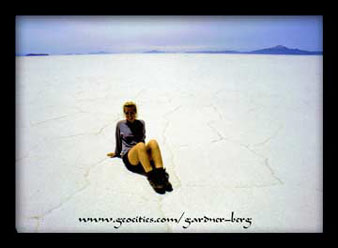

Hot by day, cold by night, and dry throughout, we travel by loaded jeep across some of the most incredible desert terrain we have ever seen. The region we'll be covering occupies the southern end of Bolivia's Altiplano - beginning with

the salt plains (Salar de Uyuni and Chiguana) then running parallel to the 3 volcanoes that borders Chile with Bolivia south to a vast basin of lakes.

the salt plains (Salar de Uyuni and Chiguana) then running parallel to the 3 volcanoes that borders Chile with Bolivia south to a vast basin of lakes.

The salt flats cover an area that was once the prehistoric lake of Minchin giving rise to speculation by geologists of a huge inland sea covering the entire Altiplano region around the end of the last Ice Age 10,000 years ago. Over time the freshwater sea had drained leaving Lake Titicaca as it's signature.

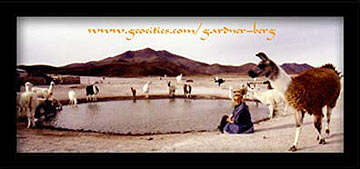

Surreal and mysterious as the land may seem to us foreigners, locals trying to eek out a living here would have to be incredibly tolerant to it. At a village we lodged at, we were watching a group of indigenous Bolivians returning their livestock by foot for the night. Judging by the anxious llamas, goats and sheep scrambling to a small water hole near us, freshwater must be of primary concern in this unforgiving land.

Surreal and mysterious as the land may seem to us foreigners, locals trying to eek out a living here would have to be incredibly tolerant to it. At a village we lodged at, we were watching a group of indigenous Bolivians returning their livestock by foot for the night. Judging by the anxious llamas, goats and sheep scrambling to a small water hole near us, freshwater must be of primary concern in this unforgiving land.

Photos and Text Copyright © 1999-2001 Gardner-Berg. All rights reserved.

Sources of Further Reading-

Abercrombie, Thomas A. "Pathways of Memory and Power: Ethnography and History Among the Andean People" 1998.

Benner, Susan E. "Fire from the Andes: Short Fiction by Women from Bolivia, Ecuador and Peru" 1998

Ferry, Stephen and Galeano, Eduardo. I am Rich Potosi: The Mountain that Eats Men" 1994.

Kolata, Alan L. "Valley of the Spirits: A Journey into the Lost Realm of the Aymara" 1996.

Luykx, Aurolyn and Foley, Douglas. "The Citizen Factory: Schooling and Cultural Production in Bolivia" 1998.

Schull, William J. and Rothammer, F. "The Aymara: Strategies of Human Adaption to a Rigorous Environment" 1990.