Amazon River, BRAZIL

| Translate: EspaŮol - FranÁais - Deutsch - Italiano - PortuguÍs - Japanese - Korean - Chinese |

Amazon River, BRAZIL

| Translate: EspaŮol - FranÁais - Deutsch - Italiano - PortuguÍs - Japanese - Korean - Chinese |

APRIL 6, 2001 -- Sadly, we leave this paradise for the long 27 hour push north towards the mouth of the Amazon River.

APRIL 6, 2001 -- Sadly, we leave this paradise for the long 27 hour push north towards the mouth of the Amazon River.

The road to Belem was a little rough - in desperate need for repair. Rains were heavy and continuously falling on the nation's real problems - poverty and hunger.

The palm plantations, green and dense slowly give way to the thatch-roofed shacks randomly spaced along the muddy road. The bus rocks side to side as the driver negotiates each pothole. And looking outside at the faces as we pass by, that same old story is told over and over, as it has done for decades. Decades of broken promises of a better standard of living stay wrapped up in black polythene and soggy cardboard boxes.

Belem is busy - over a million people concentrated on this Amazon port city of freight forwarding merchandising and warehousing. Despite the crowded bustle, the people here seem generally friendly; not really happy - but civil.

APRIL 8, 2001 -- The next couple of days is spent wandering the streets of the 'Commercio' and docks area of the city, checking on riverboat prices and their facilities, buying hammocks at the 'Ver-o-Peso'market, supplies of snacks and juices etc...

APRIL 8, 2001 -- The next couple of days is spent wandering the streets of the 'Commercio' and docks area of the city, checking on riverboat prices and their facilities, buying hammocks at the 'Ver-o-Peso'market, supplies of snacks and juices etc...

February and March 1541: 2 Spaniard processions of soldiers, supplies, conscripted Indians, weapons, horses and a large number of dogs left Quito, Ecuador on a march east over the Andes in search of cinnamon and the fabled 'El Dorado' (the so-called lost city of gold). After 100 days, cinnamon was found but they were so few and so scattered that they couldn't be farmed commercially. The Spaniards were so furious that half the Indian guides were thrown to the 2000 vicious dogs and the other half were burned alive.

The Spaniards pushed ahead manoeuvring around marshes and improvising bridges. Supplies were running low and before long the last of the pigs were slaughtered. All except 60 men turned and struggled back to Quito.

Francisco de Orellana and his men had drifted ahead eastward along the Coca and Napo Rivers with the intention of searching for food but had unwittingly discovered the biggest river on earth. They had reached the mouth of the Amazon River in 6 months.

Francisco de Orellana and his men had drifted ahead eastward along the Coca and Napo Rivers with the intention of searching for food but had unwittingly discovered the biggest river on earth. They had reached the mouth of the Amazon River in 6 months.

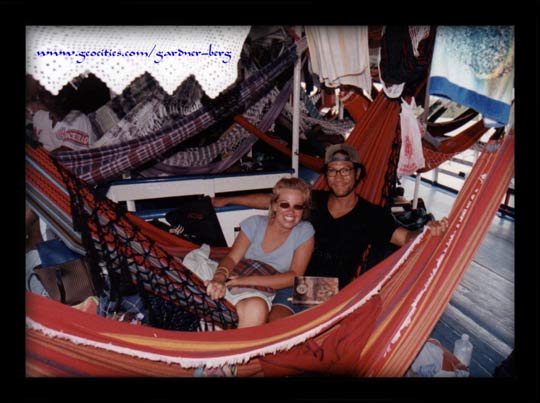

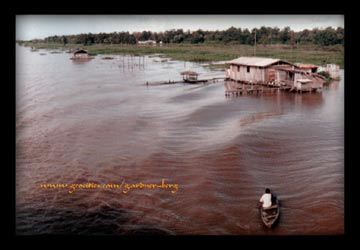

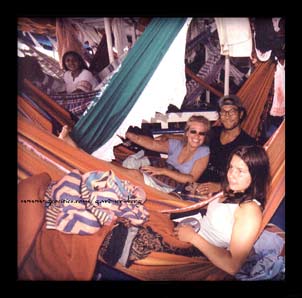

APRIL 11, 2001 -- (Noon) - We board early for guaranteed hammock space on the 'N/M Clivia' riverboat bound for Manaus. This will certainly be a new experience for us - to travel upriver for 5 days on a very crowded boat, in hammock class, on the murky waters of the largest river in the world. Sounds daunting and uncomfortable, "but it sure as hell beats bus travel".

Besides Brazilian locals joining us, 3 young travellers from Czech Replublic, USA and Sweden sling their hammocks beside ours. Once space is established, we all relax and wait as the loading of cargo below deck continues. It turned midnight when the captain sounded his intention of departure from the dock with an air horn.

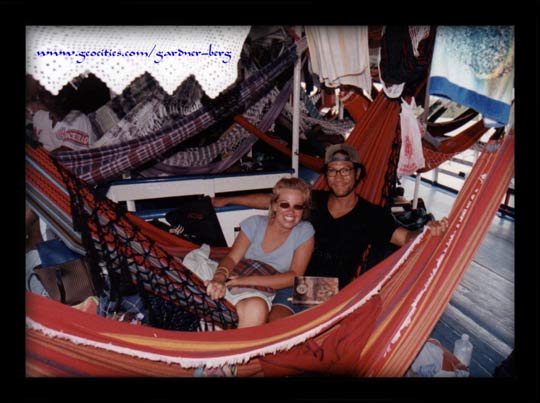

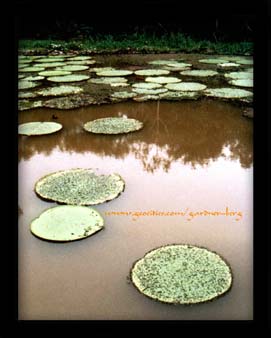

We learn quickly from the 1st day on the river that even in Amazonia there is a ghetto, not unlike those seen along tarsealed highways that we've traveled on across the continent. It gets so monotonous and sometimes it's hard to feel any emotion. Here, while plowing our way through the brown waters of this wide section of the river, our thoughts once again focus on the Indians of the rainforest; the consequences of efforts made by them to be left alone on their land is now the subject of debates on land issue, mining rights, and of course, global demands for fossil fuel and timber resources.

We learn quickly from the 1st day on the river that even in Amazonia there is a ghetto, not unlike those seen along tarsealed highways that we've traveled on across the continent. It gets so monotonous and sometimes it's hard to feel any emotion. Here, while plowing our way through the brown waters of this wide section of the river, our thoughts once again focus on the Indians of the rainforest; the consequences of efforts made by them to be left alone on their land is now the subject of debates on land issue, mining rights, and of course, global demands for fossil fuel and timber resources.

From the Conquistadors of the 16th century to the rubber/rail barons of the 19th century, the tribes now face the mining corporations of the 20th and 21st century. Encroachment, and perhaps extinction through assimilation, in the modern age seems inevitable.

In 1823, a Scotsman named Charles Macintosh became the first to manufacture rubber-coated fabric. 7 years later Thomas Hancock perfected a process to make raw rubber pliable. 1839, Charles Goodyear discovered vulcanisation, paving the way for the production of the first pneumatic tyre invented in 1888 by an Irish veterinary surgeon named John Boyd Dunlop. 4 years later Edouard Michelin made the first detachable pneumatic tyre.

In 1823, a Scotsman named Charles Macintosh became the first to manufacture rubber-coated fabric. 7 years later Thomas Hancock perfected a process to make raw rubber pliable. 1839, Charles Goodyear discovered vulcanisation, paving the way for the production of the first pneumatic tyre invented in 1888 by an Irish veterinary surgeon named John Boyd Dunlop. 4 years later Edouard Michelin made the first detachable pneumatic tyre.

Demand for rubber prompted Brazil to internationalise the Amazon following the development of latex curing techniques. These techniques were labour intensive and reserved for the 'seringueiros'- the rubber-tappers. The life of the rubber-tapper was hard and ungratifying, and no different to that of the slaves working in gold and silver mines during colonial times.

Manaus became a ridiculously wealthy metropolis of 50 000 people. Rags gave way to clothing purchased in London and Paris. Business transactions were done with gold coins in big, smart cafes where champagne, whiskey and cognac were served by specially trained staff brought in from Europe. Freighters leaving on a regular basis, filled with rubber latex, would head to New York and Liverpool, and return back loaded with bankers and white women. And to mark the pinnacle of Manaus' golden age success, a lavish Opera House was built for 3 Italian theatrical companies to perform there.

Julio Arana, head of the Peruvian Amazon Company, found that the cornerstone of his wealth, Bolivian rubber, was too far away from the marketplace. So he backed a proposed Madeira to Mamore railway. He had seized a section of land rich in wild rubber trees, deep in a disputed area between Colombia and Peru, and much closer to Manaus. It was also the homeland of the Huitoto, Ocaina, Bora and the Andoke - numbers of around 50 000. Arana then recruited a private militia of black men from Barbados, subjects of the Queen of England. He had the clever idea of setting up headquarters in London and arranging for a high-profile finance company to underwrite his firm to give it an air of respectability. The armed militia men were sent deep into the jungle to round up Indians and confine them to company-owned villages.

Julio Arana, head of the Peruvian Amazon Company, found that the cornerstone of his wealth, Bolivian rubber, was too far away from the marketplace. So he backed a proposed Madeira to Mamore railway. He had seized a section of land rich in wild rubber trees, deep in a disputed area between Colombia and Peru, and much closer to Manaus. It was also the homeland of the Huitoto, Ocaina, Bora and the Andoke - numbers of around 50 000. Arana then recruited a private militia of black men from Barbados, subjects of the Queen of England. He had the clever idea of setting up headquarters in London and arranging for a high-profile finance company to underwrite his firm to give it an air of respectability. The armed militia men were sent deep into the jungle to round up Indians and confine them to company-owned villages.

On July 20, 1912 'The Illustrated London News' ran a 2-page article on 'The Putumayo Revelations'. Photographs revealed conditions in Julio Arana's Indian camps and showed how overseers at 2 of the camps beat the Indians' legs with animal-hide whips that left disfiguring pads of scar tissue. Of the 50 000 Indians, 10 000 were killed during recruitment, 30 000 died in the camps. Each ton of rubber had cost 7 lives.

At the beginning of the 20th century, Indians had no constitutional rights in any republic along the Amazon, but the rubber scandal forced the Brazilian government to create the Indian Protection Service in 1910, designed to protect Indians from starvation, poverty, white exploitation and introduced diseases. This service was led by Colonel Candido Mariano da Silva Rondon. The service was abused after his death and replaced, by executive order, by FUNAI (Fundacao Nacional do Indio) in 1972, also currently under scrutiny.

At the beginning of the 20th century, Indians had no constitutional rights in any republic along the Amazon, but the rubber scandal forced the Brazilian government to create the Indian Protection Service in 1910, designed to protect Indians from starvation, poverty, white exploitation and introduced diseases. This service was led by Colonel Candido Mariano da Silva Rondon. The service was abused after his death and replaced, by executive order, by FUNAI (Fundacao Nacional do Indio) in 1972, also currently under scrutiny.

APRIL 14, 2001 -- We arrive in Santarem, more or less half way to Manaus. A stop at port for a couple of hours allowed some of the boat's cargo to be unloaded and pick up more passengers.

APRIL 17, 2001 -- On the homestretch to the port of Manaus, its glow in the distance signals the approach to both the heart and the end of the most civilized section of the river. The river slowly becomes congested with other passenger/cargo boats and huge tanker ships. We pass a large well-lit fuel refinery to our right. After the end of the Rubber Boom at the turn of the 20th century, another explosion of wealth and population occurred after the Brazilian government declared Manaus as a free-trade zone in 1967. Although business continues to grow, the city is crowded with the unemployed. The industrial boom still lingers today despite the isolation. We arrive in Manaus port at 11pm. Rather than wandering around the streets with our gear at this time of the night, we opt to stay one more night remaining on board. Finding a place to stay would be less hazardous in the morning.

APRIL 18, 2001 -- Orientation and a visit to the Venezuelan Consulate. Temperatures are high and the air, very humid. It's hard to take in the fact that even U.S. food franchises and westernised movie theatres have made their way here. The Shopping Mall culture has already staked a claim in the Amazon.

APRIL 18, 2001 -- Orientation and a visit to the Venezuelan Consulate. Temperatures are high and the air, very humid. It's hard to take in the fact that even U.S. food franchises and westernised movie theatres have made their way here. The Shopping Mall culture has already staked a claim in the Amazon.

APRIL 23, 2001 -- (10am) - We leave Manaus on a hot, cloudy day patched with rain - a bus bound for Boa Vista in the state of Roraima, 770kms north on a good road eventually crossing the equator and cutting sharply to the west, crossing the Rio Branco. On the west bank of the river, we join the north road to our destination. Throughout the 12 hours on this road, lands that have been slashed and burned, dominates the scenery.

Boa Vista rodoviaria possesses an unfriendly air. A wild west attitude. We certainly felt the uneasiness the entire time during the overnight layover on the station's benches.

It's said that Brazilians, in general, consider the Amazon a sort of national warehouse where their futures are locked. Loggers, miners and cattle ranchers have prospered, but many poor farmers have been 'suckered' into the illusion. Slash and burn agriculture often allows only a few years of planting rice or corn before the heavy rains and high waters wash them all away because of the thin topsoil. It's the climate, not the soil, that makes the Amazon so lush. West of here, near the Venezuelan border is the Yanomami Indian Reserves. A gold rush, which began in 1987, brought around 40 000 prospectors (garimpieros) into Yanomami territory. Pushed by greed and desperation, these armed prospectors arrived with nothing to lose. Within a couple of years, at least 1500 Yanomami were killed by diseases alone, brought in by the miners (malaria, tuberculosis, STD's). Following international pressure, the Brazilian government engaged in a massive effort to eject the miners out of the Indian land. The economic consequences were severe for the city of Boa Vista, evident even now.

It's said that Brazilians, in general, consider the Amazon a sort of national warehouse where their futures are locked. Loggers, miners and cattle ranchers have prospered, but many poor farmers have been 'suckered' into the illusion. Slash and burn agriculture often allows only a few years of planting rice or corn before the heavy rains and high waters wash them all away because of the thin topsoil. It's the climate, not the soil, that makes the Amazon so lush. West of here, near the Venezuelan border is the Yanomami Indian Reserves. A gold rush, which began in 1987, brought around 40 000 prospectors (garimpieros) into Yanomami territory. Pushed by greed and desperation, these armed prospectors arrived with nothing to lose. Within a couple of years, at least 1500 Yanomami were killed by diseases alone, brought in by the miners (malaria, tuberculosis, STD's). Following international pressure, the Brazilian government engaged in a massive effort to eject the miners out of the Indian land. The economic consequences were severe for the city of Boa Vista, evident even now.

Professor Oliveras do Santos of the University of Sao Paulo pointed out that Amazonia is a come-on. A smokescreen the 'powers-that-be' use to temporarily patch over the endemic ills from which the country suffers: poverty and hunger.

"There's a good reason for all this," he notes. "In our country, hunger is profitable. It pays off by means of fraudulent economic plans, abortive growth projects, sham incentives to sour investment, and senseless 'pie-in-the-sky' development schemes. Hunger here is a source of profits, promotional fees, rents, dividends, interest, commissions generated by loan activity, and Stock Market speculation. Gold, diamonds, coffee, cocoa, sugar, and cotton are sold over and over again before they've even been mined or harvested. Meanwhile, in the field, family farmers are deforesting parcels of land that will barely cover their own needs, and starving miners are clawing away at mountains, literally working themselves to the bone."

Photos and Text Copyright © 1999-2001 Gardner-Berg. All rights reserved.

Sources of Further Reading-

Barham, Bradford L. "Prosperity's Promise: The Amazon Rubber Boom and Distorted Economic Development" 1997

Davis, Wade. "One River: Exploration and Discoveries in the Amazon Rain Forest" 1997.

Perkins, John and Shakaim Mariano Ijisam Chumpi. "Spirit of Shuar: Wisdom of the Last Unconquered People of the Amazon".

Plotkin, Mark J. "Tales of a Shaman's Apprentice: An Ethnobotanist Searches for New Medicines in the Amazon Rainforest." 1994

Next to VENEZUELA and COLOMBIA