Museo de la Nacion, Lima, PERU

| Translate: EspaŮol - FranÁais - Deutsch - Italiano - PortuguÍs - Japanese - Korean - Chinese |

Museo de la Nacion, Lima, PERU

| Translate: EspaŮol - FranÁais - Deutsch - Italiano - PortuguÍs - Japanese - Korean - Chinese |

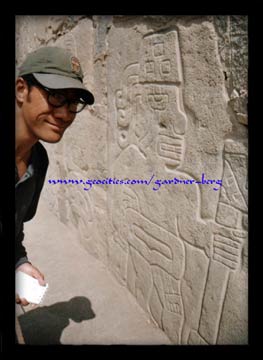

JULY 11, 2000 -- Casma, today's destination, is a sleepy little town not far from the ruins of Sechin, The following morning we walk 5 km to the Sechin temple - a walled complex consisting of large granite slabs decorated with carvings of warriors and dismembered victims. Built between 2300 and 1500 BC, the stone monoliths portray a rather graphic picture. A good scare tactic, we thought.

JULY 13, 2000 -- 370km and 6 hours down the foggy Pacific coast brings us to the nation's capital - Lima. Currently not a particularly warm city; typical city bustle and typical city prices. With the current political climate in Peru, especially now during elections, tension is building along with increased demonstrations not helped by police and military presence. We decide to set aside a week to cover as much as we can here and then quickly depart...

We start with Museo de Arqueologia de la Nacion, then the Tiwanaku Edificio because it was a good photograph. The catacombs de Iglesia de San Francisco (San Francisco Church catacombs) contains display of human bones - very interesting.

JULY 16, 2000 -- We catch a combi to the ruins of Pachacamac, 31 km south of Lima. A huge site where one can freely walk around on the dirt road circling the main centre. The word 'Pachacamac' is the name of the deity that was

considered creator of the universe and cosmos; earthquakes symbolise his anger. The image of this god is the most feared - people of that time could not look into its eyes or move anywhere near it. Only a few priests could approach, but with their backs facing it. Even during times of war, pilgrims always had passage to Pachacamac, one of the holiest places in the Andean world. Rising to prominence around 700 AD, it was later the site of an Incan sun temple.

considered creator of the universe and cosmos; earthquakes symbolise his anger. The image of this god is the most feared - people of that time could not look into its eyes or move anywhere near it. Only a few priests could approach, but with their backs facing it. Even during times of war, pilgrims always had passage to Pachacamac, one of the holiest places in the Andean world. Rising to prominence around 700 AD, it was later the site of an Incan sun temple.

The last 2 days involved a long 4 hour walk to Museo de Oro (Gold Museum) with its huge collection of precolumbian gold and a vast arms display above the vault. Rather overwhelming. No written information displayed but for US$70.00

one can purchase a book about the artifacts. Tourists everywhere here. Along with the cost of admission, there seems to be some unfairness towards student Peruvians who wish to pursue their history and heritage.

one can purchase a book about the artifacts. Tourists everywhere here. Along with the cost of admission, there seems to be some unfairness towards student Peruvians who wish to pursue their history and heritage.

JULY 19, 2000 -- We leave Lima entering the south coast heading to Pisco (237 kms south) - a fishing port. 48 kms inland along the Pisco River and passing many ruins, we ride a combi to Humay to visit Tambo Colorado. This Incan site was more or less a control station for distributing conquered people around the realms of the Inca Empire according to status/skill. An example of this form

of relocation was the surrender of the Chimu as mentioned previously. In accordance to the Inca method of government, some of the Chimu skill were assimilated in their own political and administrative system. Some Chimu nobles were even given positions in the Inca capital city - Cuzco (or Qozqo).

of relocation was the surrender of the Chimu as mentioned previously. In accordance to the Inca method of government, some of the Chimu skill were assimilated in their own political and administrative system. Some Chimu nobles were even given positions in the Inca capital city - Cuzco (or Qozqo).

JULY 22, 2000 -- Another combi van heads south from Pisco, taking us to Paracas National Reserve (15 kms away). From there we walk a hour around the bay, across flat desert-like terrain to the museum situated in between 2 major excavation sites within the reserve.

In 1925, Julio Cesar Tello Rojas (1880 - 1947), a Peruvian archaeologist discovered (and named) a new hidden pre-Inca culture - Paracas. On the strength of 2 major excavations he revealed 2 periods (or phases): Paracas Cavernas (500 - 100 BC) and Paracas Necropolis (100 BC - 100 AD).

In 1925, Julio Cesar Tello Rojas (1880 - 1947), a Peruvian archaeologist discovered (and named) a new hidden pre-Inca culture - Paracas. On the strength of 2 major excavations he revealed 2 periods (or phases): Paracas Cavernas (500 - 100 BC) and Paracas Necropolis (100 BC - 100 AD).

According to previous studies, the earliest recorded human presence in the area were found at the Santo Domingo plains not far inland from Paracas. The carbon-dating of the bones of the 3 individuals found makes them about 9000 years old, i.e. existence during Pre-ceramic period - nomadic hunter/gatherers exploiting marine resources. A small fishing village found in the same plain was

established 6000 years ago. Remains of domestic plants indicated primitive agricultural techniques used and perhaps animal domestication supplemented by seasonal gathering of shellfish from the Paracas Bay; also cactus fibre for nets and cactus spines for hooks were found along with shell jewellery. Progression toward improved farming techniques (6000 - 2000 BC) from evidence of cotton and Andean tuber, 12 kms south of Paracas Bay at Otuma - there is a dry ancient lake bed (active 1650 BC) that was used as a food source - mainly scallops (31 mounds of refuse scallop shells) found close by.

established 6000 years ago. Remains of domestic plants indicated primitive agricultural techniques used and perhaps animal domestication supplemented by seasonal gathering of shellfish from the Paracas Bay; also cactus fibre for nets and cactus spines for hooks were found along with shell jewellery. Progression toward improved farming techniques (6000 - 2000 BC) from evidence of cotton and Andean tuber, 12 kms south of Paracas Bay at Otuma - there is a dry ancient lake bed (active 1650 BC) that was used as a food source - mainly scallops (31 mounds of refuse scallop shells) found close by.

The 1925 discovery suggests the progression from scattered small settlements to that of a single society. One example may be the changes over time in the methods of burying the dead.

The 1925 discovery suggests the progression from scattered small settlements to that of a single society. One example may be the changes over time in the methods of burying the dead.

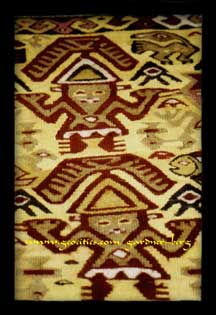

A cemetery containing about 66 bodies - some weighted to the ground with wooden stakes or heavy stone (Preceramic Period). It is known that the people of the Paracas Cavernas Period buried their dead in silo or cistern-like tombs located in the upper section of a hill called Cerro Colorado (next to the museum). Paracas Necropolis Phase showed the dead buried as funerary bundles - mummies wrapped in layers of fine weavings, reed, cactus fibre, camelid skin. 429 bundles were discovered in a nearby site by the museum.

The weavings/textiles revealed as well the practice of head-shrinking for trophy purposes. It seems that when a ritual or an actual battle was over, the head of the defeated was separated from the body. Eye sockets were stuffed with cotton cloth. Lips and eyelids were sometimes sealed with cactus spines and finally in the frontal bone a hole was made to attach a carrying cord.

The trophy head cult was wide-spread in ancient Peru. Possibly adopted by Paracas people during Chavin influence (600 - 500 BC Karwas Phase). There are beliefs related to this cult about ancestors and principles of rebirth and regeneration.

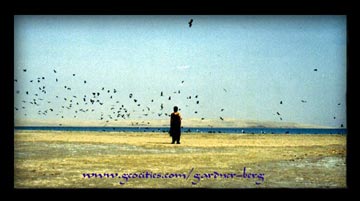

Early afternoon, we started walking back. Sudden strong winds from the desert plains head our way making our 'little stroll' a little 'exciting'. We couldn't see much in front of us and the sand whipping our faces and legs really hurt. The storm came on very fast and after an hour, it left just as quickly. The results: a dry throat, constricted breathing, and sand in every exposed orifice.

Photos and Text Copyright © 1999-2001 Gardner-Berg. All rights reserved.

Sources of Further Reading-

Paul, Anne. "Paracas Art and Architecture: Object and Context in South Coastal Peru" 1992

Peloso, Vincent C. "Peasants on Plantations: Subaltern Strategies of Labor and Resistance in the Pisco Valley, Peru." 1998