Date: 25 September, 2001

Port of Call: Onset, Massachusetts

Subject: The End of Summer

As I write this, we are anchored in Onset, Massachusetts, at the southwestern end of the Cape Cod Canal. The first strong cold front of fall is passing overhead, bringing strong gusty winds of 20 to 25 knots and gray, rainy weather. For the last week now we have been seeing and hearing daily reminders that autumn is on its way. The leaves are just beginning to gain some color, the air has the hint of a chill, and the weather-radio forecast climate summaries are now tallying "heating degree days" (36 so far) and "snowfall totals" (none, thank goodness!).

Our last CruiseNews left off smack in the middle of summer, with our return from Nova Scotia. Since then we have been taking things very easy, with mostly short sails along the coast of Maine.

The family reunion (day one, the “small” group)

Our return from Nova Scotia was timed so that we could fly from Bangor, Maine

to Wisconsin for my (Jim's) family reunion. With 11 brothers and sisters,

dozens of nieces and nephews, and what seemed like hundreds of cousins however

many times removed, it was a lot of visiting to fit into a two-day weekend.

We returned to the silence of the boat overwhelmed with blurred memories

of so many faces, fragments of conversations, and hugs, that we still don't

know what to make of it all.

Our return from Nova Scotia was timed so that we could fly from Bangor, Maine

to Wisconsin for my (Jim's) family reunion. With 11 brothers and sisters,

dozens of nieces and nephews, and what seemed like hundreds of cousins however

many times removed, it was a lot of visiting to fit into a two-day weekend.

We returned to the silence of the boat overwhelmed with blurred memories

of so many faces, fragments of conversations, and hugs, that we still don't

know what to make of it all.Pearl “gets her feet wet” in the cruising lifestyle

A few days after our return, we had a visit from my niece Pearl, and we spent

several days hiking the trails of Acadia National Park while waiting for

better weather, followed by a leisurely three-day circumnavigation of Swan's

island, still hoping for better weather. We spent more time at

anchor than under way, and more time motoring or drifting than sailing, so

it was probably pretty exemplary of what cruising is like. It was interesting

to see our lifestyle as reflected in the eyes of a non-sailor.

A few days after our return, we had a visit from my niece Pearl, and we spent

several days hiking the trails of Acadia National Park while waiting for

better weather, followed by a leisurely three-day circumnavigation of Swan's

island, still hoping for better weather. We spent more time at

anchor than under way, and more time motoring or drifting than sailing, so

it was probably pretty exemplary of what cruising is like. It was interesting

to see our lifestyle as reflected in the eyes of a non-sailor.After Pearl left, we spent a few days doing chores like laundry and provisioning, getting ready for a trip "down east". On August 19th, we headed for Roque Island in a one-day, 50-mile motor. Our favorite harbor, Bunker Cove, was already filled beyond capacity with three or four boats, so we crossed over to the other side of the island and found a spot among several other boats in Lakeman Harbor. This part of Maine is our favorite, with less development and fewer boats than elsewhere, but it is no longer the isolated area it was during our first visit in 1993. We tried to ignore the presence of other boats, which was not as difficult as one would expect, as a thick blanket of fog settled on the coast for the next three days. While we were fog-bound, we spent our time gathering mussels at low tide, walking on the beautiful crescent beach, reading our stock of "trading books", and making a foray into the woods for a tree limb of the right size to serve as a splint on the handle of our newly-broken head pump.

Roque Island is a private island and mostly undeveloped. We imagine that our view from Lakeman Harbor is much like Maine must have looked hundreds of years ago, before the land was cleared for ship timber and agriculture. It is heavily wooded with evergreen trees that grow down to the high-water line. At high tide, a small border of gray granite boulders divides green moss-covered soil and rich dark green forest from the almost black calm waters. At low tide, another 14 vertical feet of land is exposed, and the rocks there are dark, covered with a black-green growth of algae, yellow-brown seaweed, and at the low tide line, a distinctive mixture of white, blue, gray, and black that are clumps of mussel shells.

The next day we motor two hours to a much less popular harbor, up one of the dead-end rivers that feed this section of the coast, and we finally find an anchorage which we share only with a few small (and unoccupied) local boats. This is the first night we have spent in Maine this whole year that we were not in the presence of another sailboat, and we try to soak up the solitude that we know won't last. In the meantime, the head pump handle has fractured again, and I spend several hours with hammer, chisel, hacksaw and files, fashioning a more permanent repair, while making the kinds of thumping and banging noises that would not enamour ourselves to neighbors in any event.

From this point eastward, the coast of Maine changes from the craggy, island-strewn wonderland that makes for such good cruising into a straight line devoid of any usable harbors or indentations until the town of Eastport some twenty miles away. Beyond that is the Bay of Fundy, where tides grow from the 21 feet of Eastport to more than 50 feet at the head of the Bay. It is not our idea of good cruising, so we have finally reached the dead-end of our cruise: from here it's all backtracking.

To make our return trip a little more interesting, we will try to follow Maine's Inside Passage instead of our usual route of hopping offshore of most of the islands. The Inside Passage is not a formally defined waterway like the Intracoastal Waterway of the southern United States. Instead, it is an incomplete, often unmarked, labyrinthine route behind islands and out around exposed capes. I found the route loosely outlined in an article I cut from a sailing magazine several years prior. In any event, it takes us through some parts of Maine that we have never seen, so the idea of backtracking is at least spiced with the promise of new discoveries.

One of the many islands in Seguin Passage

On our first day exploring the Inside Passage, we motor up Englishman Bay

and into the shelter behind Roque Island, where we set "all plain sail" and

ease along in a gentle northerly breeze down the west side of Roque Island

in Chandler Bay. The normal route of the Inside Passage turns almost

due west from here, following Moosabec Reach past the town of Jonesport,

but Sovereign's mast won't fit below the 39 foot high bridge there, even

with 13 feet of additional clearance at low tide. Instead, we turn

south and sail down Seguin Passage, a twisting route through islands and

ledges. The chart here is covered with the blue of shallow water, the

green of ledges and shoals exposed at low tide, and the tan of many tiny

islands, plus numerous + and * symbols, denoting further submerged and exposed

nasties. In 1993 we came through here under power, all white-knuckled

and nervous, following the dotted pencil line that I had marked on the chart.

This time we confidently sail through, admiring the scenery, remarking on

the solitary shacks that sit perched atop even the tiniest islands.

We are considering spending the night in Mud Hole, a tiny hurricane hole

protected by a low-tide rock, but given the crowding we have seen all summer,

we don't expect to find room and we have another spot picked out for the

night. However, as we approach Mud Hole, two boats emerge from the

narrow entrance, and we slip in and anchor in the tiny harbor with only one

other boat.

On our first day exploring the Inside Passage, we motor up Englishman Bay

and into the shelter behind Roque Island, where we set "all plain sail" and

ease along in a gentle northerly breeze down the west side of Roque Island

in Chandler Bay. The normal route of the Inside Passage turns almost

due west from here, following Moosabec Reach past the town of Jonesport,

but Sovereign's mast won't fit below the 39 foot high bridge there, even

with 13 feet of additional clearance at low tide. Instead, we turn

south and sail down Seguin Passage, a twisting route through islands and

ledges. The chart here is covered with the blue of shallow water, the

green of ledges and shoals exposed at low tide, and the tan of many tiny

islands, plus numerous + and * symbols, denoting further submerged and exposed

nasties. In 1993 we came through here under power, all white-knuckled

and nervous, following the dotted pencil line that I had marked on the chart.

This time we confidently sail through, admiring the scenery, remarking on

the solitary shacks that sit perched atop even the tiniest islands.

We are considering spending the night in Mud Hole, a tiny hurricane hole

protected by a low-tide rock, but given the crowding we have seen all summer,

we don't expect to find room and we have another spot picked out for the

night. However, as we approach Mud Hole, two boats emerge from the

narrow entrance, and we slip in and anchor in the tiny harbor with only one

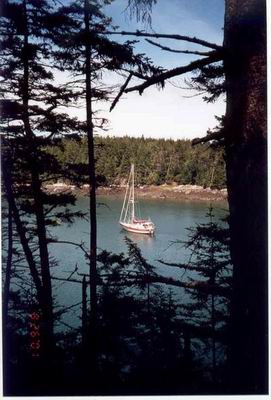

other boat.Sovereign in Mud Hole

Mud Hole is another of our favorite places in Maine. It is a narrow

fissure that extends into Great Wass Island, almost cutting the island in

two. It is nestled between two steep, wooded hills, and as I mentioned,

the entrance is closed at low tide by a rock ledge. It would be the

perfect place to ride out a hurricane if one could be guaranteed to be the

only boat there (which of course wouldn't be the case.) The area is

part of a nature preserve, and the tree-clad slopes are completely undeveloped

except for a trail that runs along the southern shore. The trail's

presence is only given away by the hushed voices of occasional hikers speaking

in low tones, as if they were walking up the aisle of a magnificent living

cathedral. We enjoy the quiet natural beauty of the place for a few

hours, in silent companionship with the other boat at anchor, until two more

sailboats enter the harbor. The enjoyable tranquility is shattered

by the shouts that often accompany the process of anchoring when the practitioners

haven't quite worked out the details, interspersed by the clanking of anchors,

the rattling of chain, and the rumble and churn of engines and propellers

over-revved in tight-quarters maneuvering. Expecting the calm to return

after this sudden flurry of activity, I am disappointed when one of the newly-arrived

crew breaks out a cell phone, sits on the cabin top, and in her loudest "telephone

voice" proceeds to pulverize the already shattered quietude for another twenty

minutes or so. Clearly cruising nowadays isn't like it used to be.

Mud Hole is another of our favorite places in Maine. It is a narrow

fissure that extends into Great Wass Island, almost cutting the island in

two. It is nestled between two steep, wooded hills, and as I mentioned,

the entrance is closed at low tide by a rock ledge. It would be the

perfect place to ride out a hurricane if one could be guaranteed to be the

only boat there (which of course wouldn't be the case.) The area is

part of a nature preserve, and the tree-clad slopes are completely undeveloped

except for a trail that runs along the southern shore. The trail's

presence is only given away by the hushed voices of occasional hikers speaking

in low tones, as if they were walking up the aisle of a magnificent living

cathedral. We enjoy the quiet natural beauty of the place for a few

hours, in silent companionship with the other boat at anchor, until two more

sailboats enter the harbor. The enjoyable tranquility is shattered

by the shouts that often accompany the process of anchoring when the practitioners

haven't quite worked out the details, interspersed by the clanking of anchors,

the rattling of chain, and the rumble and churn of engines and propellers

over-revved in tight-quarters maneuvering. Expecting the calm to return

after this sudden flurry of activity, I am disappointed when one of the newly-arrived

crew breaks out a cell phone, sits on the cabin top, and in her loudest "telephone

voice" proceeds to pulverize the already shattered quietude for another twenty

minutes or so. Clearly cruising nowadays isn't like it used to be.Gathering mussels at low tide

We spend four days sheltered in this haven, hiking the nature trail or reading

in the cockpit during the day. We gather mussels at low tide and steam

them for dinner. Each day one or two boats leave, and a few more enter,

so that the mix is always different and the cove is always full. Finally,

the weather looks right for another trip, and when the tide is high enough,

we clear the ledge at Mud Hole's entrance, and motor around the southern

tip of Great Wass Island. We improvise a return route to the Inside

Passage, cutting up Western Bay until we reach Tibbett Narrows and motor

into the harbor at Cape Split.

We spend four days sheltered in this haven, hiking the nature trail or reading

in the cockpit during the day. We gather mussels at low tide and steam

them for dinner. Each day one or two boats leave, and a few more enter,

so that the mix is always different and the cove is always full. Finally,

the weather looks right for another trip, and when the tide is high enough,

we clear the ledge at Mud Hole's entrance, and motor around the southern

tip of Great Wass Island. We improvise a return route to the Inside

Passage, cutting up Western Bay until we reach Tibbett Narrows and motor

into the harbor at Cape Split.Cape Split is strictly a working boat harbor, filled with lobster boats and draggers, but the cruising guide says there is room among the moorings to anchor, which, along with good shelter, is our main criterion for selecting a harbor. We drop the anchor in a likely place and settle in. We watch the activity as several draggers tie up to the floating dock alongside a steep boat ramp and offload hundreds of sacks, each the size of 50 pound flour bags, full of clams. A lobster boat comes by and tells us about two free guest moorings in the harbor. Since our anchor is already set, we offer our thanks but decline their use. Perhaps an hour later another lobster boat comes by with the same offer. Though they don't say it, we get the feeling that the locals would prefer it if we used the mooring instead of our own anchor, so we haul up the anchor chain and move over to one of the free moorings. In our travels we have grown so used to harbors chock full of moorings that are either reserved for $30 a night rentals, or for "private" use, that we don't even bother to look for guest moorings. We thought that they were extinct, a relic found only in cruising guides published before 1960. It was a pleasant surprise to find someplace where simple marine courtesies had not completely died out.

The next day we get under way early, and motor through the rest of this section of the Inside Passage--across Pleasant Bay, through Dyer Island Narrows, down Narraguagus Bay to Currant Island and into Pigeon Hill Bay. The route is thick with lobster buoys as well as rocks, and we weave and dodge our way through these obstacles, pushing buttons on the autopilot in a real-life version of Nintendo. When we reach Petit Manan, we turn Sovereign's bow westward for the roughly 20 miles of open water back to Southwest Harbor.

We return to Southwest Harbor just before Labor Day Weekend, and we watch in awe as the population of Mt. Desert Island seemingly disappears overnight. The town of Southwest Harbor, which had been choked with cars and people all summer long, is suddenly just a normal small town. The streets are quiet, with only an occasional pedestrian, the main intersection is no longer backed up with traffic. It is the way we remember the town from years past, and it is just another sign to us of how things have changed since we started cruising.

Sovereign fuels up at the Hinckley dock

We spend the next eight days getting ready to begin the trip south.

Our friends Ann and Charlie Bradford, who run the Island House bed and breakfast,

kindly loan us their car for a day's trip so we can go to a "real-live" Wal-Mart

and a big supermarket. We stock up with most of what we will need for

the next two months. We contact Hinckley and arrange for a mechanic

to come down and do some routine engine maintenance that is beyond the tools

I have on board the boat: checking injectors, torquing head bolts,

and the like. We also find out that the engine's raw water pump impeller,

which should be replaced about now, is only accessible by removing the boat's

hot water tank. We make a mental note to change it next time we have

the water tank out, which has already happened two or three times in Sovereign's

lifetime.

We spend the next eight days getting ready to begin the trip south.

Our friends Ann and Charlie Bradford, who run the Island House bed and breakfast,

kindly loan us their car for a day's trip so we can go to a "real-live" Wal-Mart

and a big supermarket. We stock up with most of what we will need for

the next two months. We contact Hinckley and arrange for a mechanic

to come down and do some routine engine maintenance that is beyond the tools

I have on board the boat: checking injectors, torquing head bolts,

and the like. We also find out that the engine's raw water pump impeller,

which should be replaced about now, is only accessible by removing the boat's

hot water tank. We make a mental note to change it next time we have

the water tank out, which has already happened two or three times in Sovereign's

lifetime.We say our good-byes to Ann and Charlie, and to Joe and Elsa Hayes, who were kind enough to loan us their unused mooring during our visits to Southwest Harbor, and on September 9th we are ready to leave. On Joe and Elsa's recommendation, we take a detour up Blue Hill Bay to Blue Hill Harbor. We motor only for the first hour, to charge the batteries and chill the refrigerator, then kill the engine and attempt to sail in fickle winds that, according to the forecasts, ought to be a fabulous reach in 15 to 20 knot southwesterlies. We bang around for about four hours, tacking and gybing, even setting the spinnaker for a while, and we make about seven miles. We give up, crank the engine, and motor into Blue Hill Harbor. A young man in a dinghy directs us to a mooring, saying somewhat cryptically that if we take the one he wants it's free, but if we pick up a mooring, there's a charge. We take the one he wants, and it's free.

Sovereign sails down Eggemoggin Reach

The next day we recommence our voyage down Maine's Inside Passage.

We motor down western Blue Hill Bay and into Eggemoggin Reach, which we playfully

renamed "Egg McMuffin" on our first trip here. We have called it that

ever since. It is called a "reach" because the 12-mile long passage

runs from southeast to northwest, and in Maine's prevailing southwesterlies,

whichever direction one sails would theoretically result in sailing on a

beam reach. In our previous experience it had always been Egg McMuffin

Beat, because the wind was always blowing straight up or down the waterway

instead of across it. This time, however, the wind does what it is

supposed to, and we close-reach in winds of 15 to 20 knots and flat seas.

The sailing is so perfect that I even hop in the dinghy with the camera,

and zip around photographing Sovereign from all angles while Cathy sails

her along at a brisk six knots. By the time we reach the western entrance,

we have to shorten sail because the wind has built well beyond twenty knots.

We beat out the entrance, around Head of the Cape, then run up East Penobscot

Bay to Castine and Smith Cove.

The next day we recommence our voyage down Maine's Inside Passage.

We motor down western Blue Hill Bay and into Eggemoggin Reach, which we playfully

renamed "Egg McMuffin" on our first trip here. We have called it that

ever since. It is called a "reach" because the 12-mile long passage

runs from southeast to northwest, and in Maine's prevailing southwesterlies,

whichever direction one sails would theoretically result in sailing on a

beam reach. In our previous experience it had always been Egg McMuffin

Beat, because the wind was always blowing straight up or down the waterway

instead of across it. This time, however, the wind does what it is

supposed to, and we close-reach in winds of 15 to 20 knots and flat seas.

The sailing is so perfect that I even hop in the dinghy with the camera,

and zip around photographing Sovereign from all angles while Cathy sails

her along at a brisk six knots. By the time we reach the western entrance,

we have to shorten sail because the wind has built well beyond twenty knots.

We beat out the entrance, around Head of the Cape, then run up East Penobscot

Bay to Castine and Smith Cove.We decide to make the next day a lay day, as the forecast calls for Hurricane Erin, well off the coast, to push large swells into our area. Even though we are sailing the "Inside Passage", it is not really protected from the southerly or southeasterly swells we are expecting, so we stay put. This is September 11th, and as we are listening to classical music on NPR, they break in with a report of a plane crash into the World Trade Center, then quickly return to normal programming. A few minutes later someone on VHF channel 16 makes an announcement, suggesting people turn on any commercial radio station to listen to events of "national significance". We turn on our TV to ABC, the only channel we can receive, and for the next ten hours we watch in stunned disbelief as the events of the day unfold. For a while, tired of listening to Peter Jennings, we turn off the volume, and listen to short-wave broadcasts from the BBC, while watching the pictures from ABC. The voice is different, but the news is the same. Finally, well past our normal bedtime, we turn off the TV and try to sleep away the horrors of the day. It doesn't work. We are up early the next morning, watching ABC once again, seeing the same horrors from new angles, and listening to more information and misinformation trickle in.

After a day and a half of focusing our attention on nothing but death and sorrow, we have to do something else, so even though the forecast is not perfect, we get under way. The details of course and distance, speed and time, and the physical needs of raising anchor and steering at least partially occupy our attentions as we travel the two and a half hours to the island of Islesboro, Maine. Once there, the TV is on again, and this time CBS comes in best, so Dan Rather tells us what we missed in our few hours of respite.

"Boating therapy" seemed to work well for us, so the next day we get under way after several hours of morning news, and take six hours to motor from Islesboro, down West Penobscot Bay, through Mussel Ridge Channel, and up the St. George River to a little place called Pleasant Point Gut. The scenery passes by in a haze, as if we are in a thick fog, but it is a fog created by our own thoughts; atmospheric visibility is not a problem. We try to keep busy with navigation, dodging lobster buoys, making lunch and operating the watermaker, but at the end of the day there is still the TV, with news that doesn't get any better.

The next day, Friday, is rainy with small craft advisories, which does not sound like good conditions for more "boating therapy", so we settle into a day of idleness, reading when we can muster enough concentration, and otherwise watching TV. I think about watching a movie to take our minds off things, but all we have are the same old movies we have watched a hundred times. Still, I go through a mental list. "Airforce 1": Terrorists take over the President's plane. No way, too close to home. "Independence Day": Aliens invade the Earth and blow up the White House from space. No, ditto. "Jewel of the Nile": A power-hungry middle-eastern leader tries to convince a romance novelist to write a whitewashed biography that ignores his plan to usurp religious and political control of the region. Well...no. Let's see, there's "Splash": Set in southern Manhattan, with the twin towers pictured on the dust jacket, that one is out. Even our only Walt Disney cartoon isn't safe, as "Aladdin" reminds us too much of what's going on. I give up, and try to concentrate on the relative sanity offered by one of our trading books, a murder-mystery set in Los Angeles where people only get killed one at a time.

The weather forecast for Saturday is better, and it also offers a huge task of busywork beforehand: a long GPS route of 24 waypoints, each of which is plotted on a chart, tabulated on paper, entered into the GPS with much button pushing, then cross-checked to see if the GPS calculated courses and distances match my own. On paper, the trip takes us through the harbor of Friendship and across the northern reaches of Muscongus Bay, and culminates with a trip through a swing bridge in a narrow, tide-strewn channel. Perfect.

It takes us nearly two hours of motoring to get through the tricky sections. The rain of the previous day has stopped, and left behind is a bright, sparkling day. We pass through fields of lobster buoys: dark fingers of water are speckled with dots of bright primary colors almost glowing in the crisp, slanting sunlight of a northern morning. On each side of us are rock ledges covered with yellow-brown seaweed, and islands large and small whose boulder-strewn tidal zones rise to caps of dark, pointed firs. The lobster boats we pass seemed to be engaged in a gyrating dance as they gaff lobster buoys, circle around while the crew cleans and rebaits the traps, and then prances off towards the next buoy in a puff of exhaust and splash of wake. After we clear the twisting passageways behind the northern islands of Muscongus Bay, our path opens onto the straight expanse of Muscongus Sound, and we raise the mainsail, unroll the yankee jib, and sail wing-and-wing almost due south. As we pass the harbor of Round Pond, a small schooner of about the same size as Sovereign joins us, and we both sail southward at a leisurely pace, with a fair wind and favorable current. The wind veers to the northeast, and as we reach toward Pemaquid Point, the schooner eases ahead of us, taking advantage of her best point of sail. The wind continues to veer as we approach the point, and in perhaps half an hour it shifts from due north to due south. A series of four tacks, just enough to be challenging but not too much to seem like work, push us around the point and past the schooner, as the close wind angle now favors Sovereign's cutter rig. As if on cue, a 180° wind-shift occurs at the perfect time, so that we enjoy favorable winds almost the whole day. Finally, in a building southerly, we close-reach to the east-southeast across Johns Bay, then turn northeast for a fast reach up Booth Bay. It is a rare treat of fast, fun sailing in flat seas. It is just what we need.

We spend the 16th, my birthday, in Townsend Gut, just west of Boothbay, Maine. Cathy works all morning baking up a storm, producing my favorite meal of turkey, stuffing, and all the trimmings. In the late afternoon, after an early dinner, we dinghy into Boothbay to look around the town, dispose of some trash, and get a few fresh groceries. On the way in to town, we are stopped by a Maine Game Warden. He informs us that Maine does not recognize U.S. federally documented vessels, or foreign documented vessels for that matter, and if we have a boat in Maine, regardless of where we are from or how short a time we are here, if it has an engine, then it must be registered in Maine. We are fortunate that he does not ticket us, but we are not happy with the encounter. After a similar incident in Florida a number of years ago, we decided to stay out of that state. We don't look forward to a permanent boycott of Maine waters. I think about firing off an irate e-mail or two, but when we get back to the boat we find that the computer has died. As our only regular means of communicating with the outside world, the loss hits us hard, but a little thought about recent national events reminds us how trivial our problems are. I pull out a voltmeter and halfheartedly look at fixing the computer, but with no luck. That night we pull the outboard off the dinghy, making it a rowboat. Now we only have one illegal boat in Maine, instead of two.

The next morning is Monday. We raise anchor, and motor into Boothbay, which takes about 45 minutes. We pick up a mooring as close to the dock as we can, and row the inflatable ashore. We canvass the town, and eventually find a place where we can get access to the Internet, about a twenty-minute walk from town, for $12/hour. Ouch. We log on and spread the word about our lack of contact, then go back to the dock, row out to Sovereign, and slip the mooring.

We have to skip another part of the Inside Passage, this time the upper reaches of the Sheepscot and Kennebec Rivers, once again because of the height of our mast. We leave Booth Bay, motor across Sheepscot Bay, past Cape Small, and up the New Meadows River to a wonderful harbor called The Basin. Once inside, it looks like an inland lake. There are trees all around, and no hint of the dogleg passage that leads back out to open water. We drop anchor in perfectly calm water with plenty of swinging room.

Tuesday is a lay day, with forecasts of big swells from Hurricane Gabrielle passing well off the coast, so we stay put. TV coverage here isn't great, and the networks have resumed more normal scheduling, so we aren't compelled to watch it all day as we did a week ago. We are starting to come to terms with the blow that has been dealt our nation. We aren't aware of anyone we know personally who was lost in the tragedy, so our grief is the same national grief that all Americans share, not the intense personal mourning of some. Still, even in an isolated cove miles from anywhere, we can see signs that things are not normal. Huge gray jet aircraft with Navy markings take off every few minutes from an airbase somewhere to our north and overfly our area; Orion P3 four-prop aircraft patrol the coastal airspace; every few minutes the Coast Guard broadcasts announcements of security zones set up at the perimeter of Coast Guard, Navy, and defense contractor sites in the area.

As a way to do something, anything, I start stripping down our dead computer, and finally make my way in far enough to find a loose screw. Because I can't completely disassemble the computer, it takes a few minutes of holding it upside down and shaking it, in a motion like that used to clear the screen of an Etch-a-sketch, before I am finally able to dislodge the screw and re-assemble the computer. I hold my breath and turn on the power switch. It works! We are back in touch with the world!

The water gets rough as we approach Jaquish Gut

The fuzzy TV coverage in The Basin, as much as anything, makes us anxious

to move on, so the next day, with forecasts of 10 knot winds and 2-4' seas,

we set out on our final leg of the Inside Passage. We motor back down

the New Meadows River and behind some of the small islands of eastern Casco

Bay. About an hour into our trip, the Coast Guard announces on the

radio that there is an updated weather forecast. There is now a small-craft

advisory for seas of up to seven feet. Some bright boy at the National

Weather Service apparently forgot that Tropical Storm Gabrielle is out in

the Atlantic churning things up. Still, we are a third of the way to

our destination, and things don't look too bad, so we continue on.

At one point in the trip we have to pass through a place called Jaquish Gut.

The Inside Passage article I have been using as a guide says, "The soundings

run as low as 7 feet, so you may need to go through on a rising tide, and

it's so narrow you can almost shake hands with the beachcombing tourists

as you pass by." It doesn't say anything about going through with seven-foot

swells from an offshore tropical storm. In fact, on the chart it doesn't

even look possible to pass. But as we approach the Gut, a lobster boat

passes us and goes through, so we know exactly where to go. The Gut

itself is a tiny cut between two granite islands, impossibly close together.

Down the center of this narrow black strip of water is a white stripe of

spume, like tide rips which are often present at tidal changes. It

looks like the stripe down the back of a skunk, and I steer strait along

the skunk's spine as the boat lifts and falls in the swell and waves crash

on the rocks nearby. Luckily at the instant we get to the narrowest

part of the Gut, our camera runs out of film as Cathy frantically tries to

document the experience on film, and she is so busy changing the film that

she doesn't have time to be scared. In roughly a minute it is all behind

us. In another 90 minutes we are safely anchored in the little harbor

at Jewell Island.

The fuzzy TV coverage in The Basin, as much as anything, makes us anxious

to move on, so the next day, with forecasts of 10 knot winds and 2-4' seas,

we set out on our final leg of the Inside Passage. We motor back down

the New Meadows River and behind some of the small islands of eastern Casco

Bay. About an hour into our trip, the Coast Guard announces on the

radio that there is an updated weather forecast. There is now a small-craft

advisory for seas of up to seven feet. Some bright boy at the National

Weather Service apparently forgot that Tropical Storm Gabrielle is out in

the Atlantic churning things up. Still, we are a third of the way to

our destination, and things don't look too bad, so we continue on.

At one point in the trip we have to pass through a place called Jaquish Gut.

The Inside Passage article I have been using as a guide says, "The soundings

run as low as 7 feet, so you may need to go through on a rising tide, and

it's so narrow you can almost shake hands with the beachcombing tourists

as you pass by." It doesn't say anything about going through with seven-foot

swells from an offshore tropical storm. In fact, on the chart it doesn't

even look possible to pass. But as we approach the Gut, a lobster boat

passes us and goes through, so we know exactly where to go. The Gut

itself is a tiny cut between two granite islands, impossibly close together.

Down the center of this narrow black strip of water is a white stripe of

spume, like tide rips which are often present at tidal changes. It

looks like the stripe down the back of a skunk, and I steer strait along

the skunk's spine as the boat lifts and falls in the swell and waves crash

on the rocks nearby. Luckily at the instant we get to the narrowest

part of the Gut, our camera runs out of film as Cathy frantically tries to

document the experience on film, and she is so busy changing the film that

she doesn't have time to be scared. In roughly a minute it is all behind

us. In another 90 minutes we are safely anchored in the little harbor

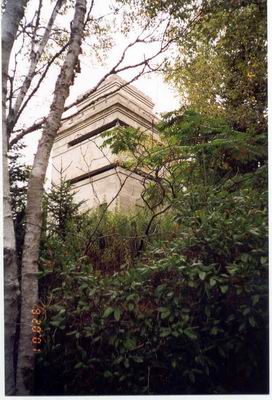

at Jewell Island.Abandoned watch tower at Jewell I

Jewell Island, as its name implies, is a gem in the crown of Casco Bay.

It is part of a nature preserve, so there are no permanent residents, only

occasional campers. The harbor itself looks on the chart like the small

gap between the thumb and the rest of one's right hand placed palm down on

a flat surface. Unfortunately, the thumb is not quite connected to

the rest of the hand, leaving a small gap, which, at high tide, allows swells

to roll into the harbor. We spend three days here, rolling at anchor

for a few hours around high tide twice each day, as a series of closely spaced

cold fronts pass overhead, stirring up the seas and bringing unsettled weather.

During our stay, we go ashore and hike to the southern tip of the island.

We climb up into the two concrete, multi-tiered anti-aircraft towers built

during World War II, which are now abandoned and left to decay as the brush

grows up all around. We brought a flashlight and explored a large underground

concrete bunker with a labyrinth of tiny pitch-black rooms set around a T-shaped

central corridor, the purposes of which we could only imagine. Walking

around these relics, and the ruins of other less permanent buildings on the

island, makes us think of the events surrounding the last time they were

used, of World War II and the aftermath of Pearl Harbor, when Americans were

worried about hostilities on their own soil. On previous visits they

were only spooky ruins, but now they are a silent and somber reminder of

America's history, and perhaps its future.

Jewell Island, as its name implies, is a gem in the crown of Casco Bay.

It is part of a nature preserve, so there are no permanent residents, only

occasional campers. The harbor itself looks on the chart like the small

gap between the thumb and the rest of one's right hand placed palm down on

a flat surface. Unfortunately, the thumb is not quite connected to

the rest of the hand, leaving a small gap, which, at high tide, allows swells

to roll into the harbor. We spend three days here, rolling at anchor

for a few hours around high tide twice each day, as a series of closely spaced

cold fronts pass overhead, stirring up the seas and bringing unsettled weather.

During our stay, we go ashore and hike to the southern tip of the island.

We climb up into the two concrete, multi-tiered anti-aircraft towers built

during World War II, which are now abandoned and left to decay as the brush

grows up all around. We brought a flashlight and explored a large underground

concrete bunker with a labyrinth of tiny pitch-black rooms set around a T-shaped

central corridor, the purposes of which we could only imagine. Walking

around these relics, and the ruins of other less permanent buildings on the

island, makes us think of the events surrounding the last time they were

used, of World War II and the aftermath of Pearl Harbor, when Americans were

worried about hostilities on their own soil. On previous visits they

were only spooky ruins, but now they are a silent and somber reminder of

America's history, and perhaps its future.While we were at Jewell Island, the autumnal equinox occurred, a series of three cold fronts passed within three days, and, as if on cue, the first few leaves of the birch trees on the island began their change from green to golden yellow. Autumn was instantly here. It was as if all at once, the planets, the atmosphere, the earth, and even the politics of man, are all showing signs of the changes that have been creeping up on us, that the careless days of summer are over, and that there is a new chill in the air. We can only hope that winter will not be too harsh, and that spring will follow bright and fresh, as it always does.

Smooth sailing,

Jim and Cathy