A Summary on the History of the Joust

Text and Photos from:The Age Of Chivalry

by Liliane and Fred Funcken

family coat of arms awarded to the Lords of Essling, Austria

Knightly sports developed very early on as a result of a combination of factors, namely a natural inclination towards weapons and feats of military valour, a need for regular training and a desire to show off one's skill and physical prowess in public.

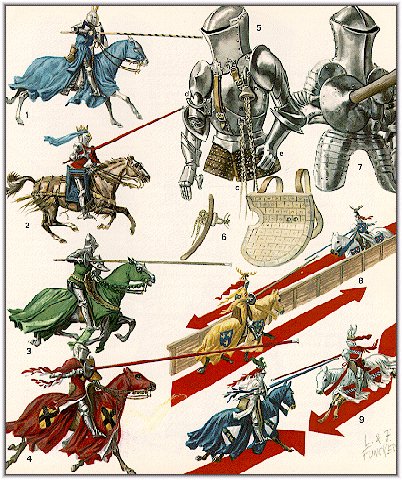

The joust, a combat between two horsemen armed with lances, must certainly have been the earliest known form of these courtly fights, if only because it was the simplest. The use of special tips for the lances and light shafts that would break more easily was probably common practice in these early jousts, since it is hard to imagine how a knight wanting to train at the same time as practice a violent sport would have failed to take this basic precaution--regardless of how anxious he was to show off his skill.

Nevertheless it is clear that combats of this kind took on quite a different aspect when the opponents involved allowed personal grudges to enter into things. this must have been quite a common occurrence, yet even in this situation the rules of jousting and chivalry laid down that only the helmet or the shield could be struck. What is far more likely to have happened is that two deadly enemies chose a more private place in which to settle their quarrel--always assuming they did not turn the honourable institution of the duel into a common ambush! It would be a grave mistake to take too exalted a view of chivalry; this same epoch which is celebrated in so many courtly romances was riddled with instances of base or dishonourable conduct.

Jousting, which was very popular with the spectators, usually marked the beginning or end of a tournament. When not a part of a tournament these confrontations were called "great and plenary jousts, open to all comers."

The tournament, which was also called the "tourney", is generally thought to have originated in France. In the 9th century, the historian Nithard, who was Charlemagne's grandson, described a tournament held in Strasbourg around 842 in which two equal parties of Saxons, Basques, Austrasians and Bretons met one another. However, a reference to a similar encounter in Barcelona, as far back as 811, has been recorded, and most major tournaments between the 10th and 12th centuries were in fact held in Germany, where they are said to have been organized by Henry the Fowler (876- 936).

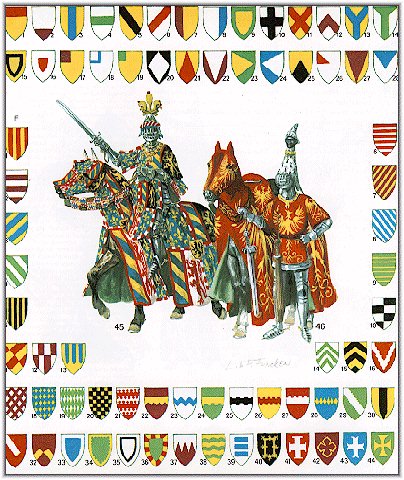

The brutal developments that had taken place in tournaments so often had fatal consequences that in the 9th century Pope Eugene II anathematized them. His successors followed suit: Innocent II, Eugene III, and Alexander III in the 12th century, Innocent IV in the 13th century and Clement V at the beginning of the 14th century, excommunicated all "tourneyers" and forbade the burial of victims in consecrated ground. It made no difference, however, and the slaughter continued, despite the strict set rules laid down by Geoffrey de Preuilly at the beginning of the 11th century.

The names of the most famous victims of this dangerous passion have been preserved in medieval chronicles. Geoffrey de Magneville, Count of Essex, killed in 1216: Florent, Count of Hainault and Phillip, Count of Boulogne, both killed in 1223: the Count of Holland in 1234: Gilbert of Pembroke in 1241: Hermand de Montigny in 1258: John of Brandenburg in 1269 and John, Duke of Brabant, in 1294. In 1240, at the tournament of Nuys, near Cologne, sixty knights and squires perished, trampled or crushed to death by their horses. The most deplorable incident of all was the death of William Montagu, who was killed by his father in 1382. Yet alongside these unfortunates a breed of experts was already evolving who can be likened to the tennis champions of today. These men travelled all over Europe winning fame and fortune simply by virtue of their skill at this dangerous sport. In the 13th century William Marshall, who was to be regent of England during the minority of Henry III, amassed considerable wealth by this method.

Following the example of the Popes, monarchs themselves banned tournaments on occasion, though only for a limited period.

In England they were proscribed by Henry II during the 12th century and then restored by his successor, Richard I. In 1299, they were again banned by Edward I, despite the fact that he himself had led eighty knights to the tournament at Chalons in 1274. They reappeared in even greater strengths during the reign of Edward III, who issued safe-conducts to any Frenchmen willing to meet his knights in courtly combat. (This, incidentally, took place at the height of the Hundred Years War, two years before Edward inflicted a crushing defeat on the French at Crecy, in 1346). The famous Order of the Garter was to be created shortly afterwards, in the course of another great tournament.

The rules and rituals of these warlike occasions grew more complicated as time went on. The increasing influence of women resulted in the dangers being greatly reduced and the tournament being transformed into an exhibition of gallantry as much as a display of sporting prowess by the 15th century.

The End.