The Garden City Movement and City Planning in the Early Twentieth Century

Through the development of domestic architecture, especially that of country houses, the Arts and Crafts movement paved the way for new trends in city planning.

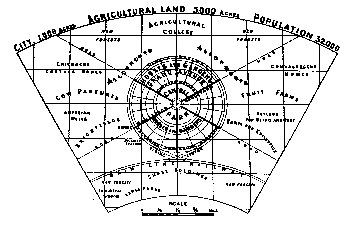

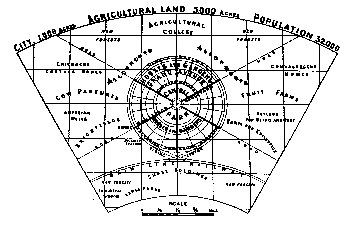

In 1898 Sir Ebenezer Howard, who had been thinking about a quality of life better than that possible in overcrowded and dirty industrial towns, published his book Garden Cities of Tomorrow. In it he described his vision of an ideal township, an independent garden city in the country, for about 32000 people, consisting of rural housing estates, sufficient arable land, shopping facilities, cultural institutions and a Crystal Palace.

above: Howard, 'Rurisville', schematic garden city from his Tommorrow

Howard actively promoted his plans, and organized the financing of the projects. In 1903 work started on the execution of plans by Barry Parker and Raymond Unwin for the first garden city, Letchworth near London. Further towns followed throughout the world. Although the majority of garden cities grew into viable units, they remained isolated and ineffective to alleviate the results of population explosion.

Otto Wagner, who believed in the large town as appropriate form of settlement for the twentieth century, turned against the garden city ideology. He demanded communal property for the expanded areas of the conurbation and flexible planning in line with the varying requirements of the population. In his plans for the development of Vienna's District XXII (1911), he outlined a Classicist monumental project that was to combine a variety of types in a large "town within a town" for a population of 150000.

The Early Rationalists saw alternative solution to the problems of city planning. The Futurist Marinetti said "We state that the beauty of the world has been enriched by a new form of beauty, that of speed". Speed, the essences of the Futurist movement. Among its member, included architects, and the most important figure in this group being Antonio Sant'Elia.

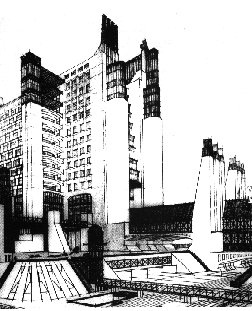

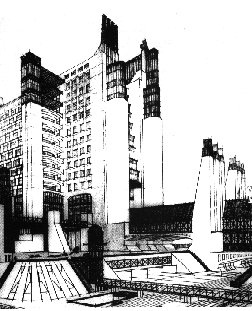

In 1913, Sant' Elia started work on his large project for the Citta Nuova. It comprised perspective drawing and sketched visions of a metropolis of the future. With terraced skyscrapers, the internal structures of which were exposed, and elevator shafts separated from the main structural body. Grandiose traffic routes with intersections at various levels; slim steel or concrete bridges connecting the various shafts, high-rise apartment buildings, and roadways; as well as bold, monumental, obliquely supported structures that gave no indication of their function. These were new and revolutionary form of architecture. They were attempted to break with the past and progress to an entirely new form of architecture, and they revealed the force and magnificence of Sant' Elia's dreams.

above: Sant'Elia, casa a gradinata for the Citta Nuova, 1914.

Tony Garnier, French architect and socialist, Tony Garnier, designed his project for a Cite Industrielle during 1899 and 1904. For a population of 35000 he planned a housing estate, a housing centre, industrial buildings, a railways station and all necessary public buildings, but no barracks, police stations, prisons, or churches, since these would no longer be required by the new society. Garnier created a revolutionary concept of a city that contained all the essential elements of rational urban planning. Garnier's project for a 'Cite Industrielle', first exhibited in 1904. A project that demonstrated his belief that the cities of the future would have to be based on industry.

Garnier's industrial city of 35000 in habitants was not only a regional centre of medium size, sensitively related to its environment, but also an urban organization that anticipated in its separate zoning the principles of the CIAM Athens Charter of 1933. It was a socialist city, without walls or private property, without church or barracks, without police station or law courts. A city where the entire unbuilt surface was public parkland.

City planning was the main concern of architectural Rationalism.

In 1922 Le Corbusier designed plans for a Ville Contemporaine, a contemporary city for a population of three million. He based his ideas on the concept of Tony Garnier's Cite Industrielle and on the aesthetics of Antonio Sant' Elia's Citta Nuova. However, he aimed not for an industrial city but a complex metropolis with numerous and varied functions, as a diagrammatic solution to the traffic and housing problem through a ruthlessly geometrically organized separation of functions. Ville Contemporaine already contains all the essential elements of Le Corbusier's urban theories: an orthogonal geometric grid skyscrapers in the form of single or multiple slabs, apartments with direct insulation and ventilation, generous green spaces between the individual high-rise buildings and separation of access for vehicles and for pedestrian.

The plan stressed on the vertical rather than the horizontal development of buildings. For example, in Paries city centre, the Plan Voisin project (1925), proposing the replacement of the historic urban structure by 18 super-skyscrapers. Further urban project followed, for example, the Ville Radieuse project dating from 1930-36. This was a transformation from the 'hierarchic' Ville Contemporaine of 1922 to the 'classless' Ville Radieuse of 1930, which showed the zoning in parallel bands, each band assigned for different use.

Recommended reading(s):

Back to top

Back to Modern Architecture

Back to Home