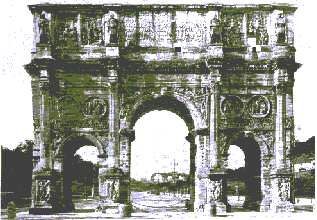

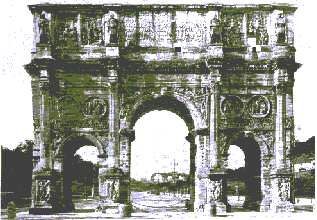

fig.2

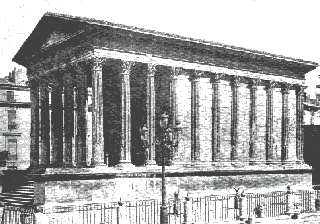

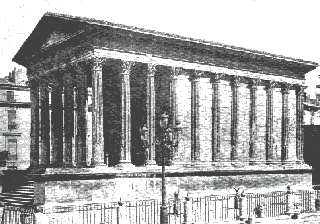

fig.3

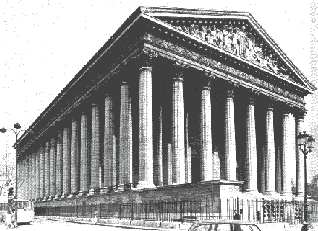

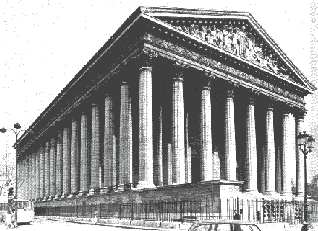

fig.4

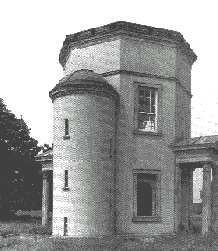

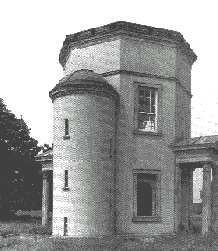

fig.5

fig.6

fig.7

fig.8

fig.9

fig.10

fig.11

fig.12

fig.13

fig.14

| Kaufmann, E. | Architecture in the Age of Reason Harvard University Press, 1955 |

| Middleton, R. and Watkin, D. | Neoclassical and 19th Century Architecture (2 vols), London, 1987 |

| Stillman, D. | English Neoclassical Architecture (1st vol), 1988 |

| Summerson, J. | Architecture in England 1530-1830 Pelican, 1968 |

| Summerson, J. | The Architecture of the 18th Century 1986 |

| Summerson, J. | The Classical Language of Architecture London, 1980 |

| Watkin, D. | English Architecture: a concise history London, 1979 |

fig.2 |

|

fig.3 |

fig.4 |

fig.5 |

fig.6 |

fig.7 |

fig.8 |

fig.9 |

fig.10 |

fig.11 |

fig.12 |

fig.13 |

fig.14 |