The Lobotomist

|

||

| FRANK FREEMAN remembers hiking with his

father in the Woods, going fishing with him, and setting off on cross-country driving

trips that could last for weeks. He also recalls one occasion in 1952 when he helped his

father perform a trans-orbital lobotomy on a patient.

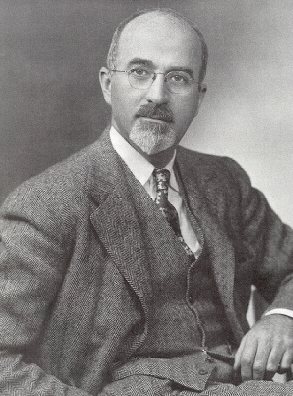

The procedure, which his father, Walter J. Freeman, popularized and perfected, involved first knocking the patient unconscious with two or three jolts of electricity from an electroshock therapy machine. "I was there to hold the person's legs down," Frank Freeman says. "We all went for a ride when he threw the switch." After the convulsions subsided and the patient lay insensate, Walter Freeman lifted the patient's eyelid and inserted an ice pick-like instrument called a leucotome through a tear duct. A few taps with a surgical hammer breached the bone. Freeman took a position behind the patient's head, pushed the leucotome about an inch and a half into the frontal lobe of the patient's brain, and moved the sharp tip back and forth. Then he repeated the process with the other eye socket. "I was kind of impressed," Frank Freeman recalls. "He made it look so easy." FOR WALTER FREEMAN, a neurologist and psychiatrist who practiced in Washington for 28 years, it was easy. He kept record of 3,439 lobotomies he performed during his career. His technique of trans-orbital lobotomy was such a breeze that he could teach it in a day or two to state-hospital psychiatrists who, like himself, had no certification in surgery. Freeman gave lobotomies to children, adults, old people, and people with depression, manic-depression, schizophrenia, obsessive-compulsive disorder and a variety of undiagnosed psychiatric illnesses. He believed in lobotomy, defended it, promoted it and demonstrated it during psychosurgical road trips he took to more than 55 hospitals in 23 states. He felt certain that lobotomy could return |

psychologically disabled people, many of whom had no

other prospect of effective medical treatment and who lived in oppressive psychiatric

wards, to useful lives.

"Lobotomy gets them home" was his motto. Freeman's enthusiasm for lobotomy, which developed through his work with his colleague James Watts at George Washington University Hospital, began a wave of psychiatric surgery that was used on 40,000 to 50,000 Americans between 1936 and the late 1950s. It is difficult to say how many benefited. Few controlled studies were ever conducted, and Freeman's own summaries of his results were difficult for others to interpret. By the time Freeman died in 1972, his theory that mental illness could be cured by physically attacking the brain's frontal lobes had been discredited. While things have not exactly come full circle since then, there is much in today's neuropsychiatric climate that Freeman would recognize. Many psychiatrists no longer practice "talk" therapy and instead treat their patient's brains. In 1999 Surgeon General David Satcher issued a 450-page report on mental health making the case that many psychiatric illnesses are actually brain disorders, and that often the most effective treatments affect the transmission of messages in the brain's neuro-pathways. Freeman would fully agree. He believed that lobotomy succeeded because it severed neural connections between the frontal lobes of the brain and the thalamus, which he characterized as the seat of human emotion. Mentally ill people were too self-aware, he maintained, and their overactive emotions caused them to obsess about their problems. Sixty years ago few of Freeman's colleagues, especially psychiatrists for whom psychotherapy was the preferred treatment for psychiatric disorders, believed that brain |

|