OH!

![]()

![]()

Long, long ago, in the bygone days before our fathers and grandfathers were born, there lived a poor man and his wife. They had only one son and not a lad to be proud of, either, but a loafer like no other! He sat half-dressed on the stove playing with grains of millet day in and day out and would not so much as move a finger to help his parents, or himself, either. He was nearly twenty years old, but he sat on the stove and never climbed down, and if food was placed before him he would eat; but if it was not, rather than get it for himself, he would do without.

This made his mother and father very sad indeed.

"What are we to do with you, son!" they said. "Other people's children help their parents, but you only eat!"

But whatever they said was as nothing to him, and he went on sitting there and pouring the millet grains from one hand to the other. Lads of only four or five are often a help to their parents, but though this one was a grown man and so tall that he nearly reached the ceiling he often forgot to dress properly and did not know how to do anything.

The mother and father grieved and sorrowed for a long time, and one day the mother said:

"What can you be thinking of, husband! Our son is a grown man, but he doesn't know how to do anything at all. Why don't you send him out to work or to learn a trade so that he will know how to do something at least!"

To this the father agreed, so he had a tailor take on his son as an apprentice. But the youth only stayed with the tailor for three days. He ran away from him, came back home, and, climbing up onto the stove, began playing with grains of millet again.

His father scolded and thrashed him and then set him up with a bootmaker, but he ran away from him too. He thrashed him again and sent him to a blacksmith's, but all in vain, for the same thing happened.

The father was more grieved than ever.

"What am I to do?" said he. "I think I'll take him to another kingdom and get someone there to teach him a trade and perhaps he won't be able to run away so easily."

And taking his son, he set out with him for another kingdom.

On and on they walked, and whether a long time passed or a short nobody knows, but at last they came to a forest so thick and dark that one could see nothing there save the sky above and the ground below. Feeling tired, they looked around for something to sit on. They saw a burnt tree stump by the-roadside, and the father said:

"I think I'll sit on that tree stump and rest for a spell!"

And with an "Oh, how tired I am!" he let himself down on the stump.

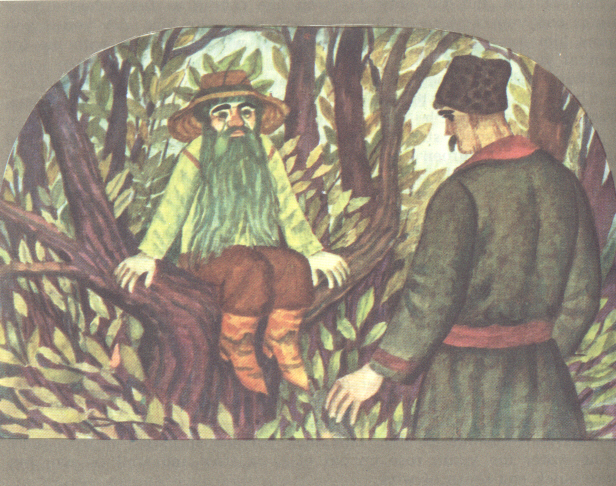

But no sooner were the words out of his mouth than lo and behold! a little old man with a bright green beard that reached to his knees climbed up out of the stump.

"What is it you want, my good man?" he asked.

The father stepped back in surprise for where could anyone so strange have come from! and said:

"I want nothing from you!"

"Why did you call me then?" the little old man returned.

"Who are you?"

"I am Oh, the tsar of the forest! Come, now, tell me why you called me?"

"What a thing to say! I never even thought of it!"

"Didn't you, now! You said 'Oh!, I heard you."

"Yes, but only because I was tired."

"Where are you going?" Oh asked.

"Wherever the road leads," the father replied. "I'm trying to find someone who will teach this silly lad of mine a trade and put a little sense into his head. Perhaps strangers will do what I am unable to. At home, he kept running away from all the people I left him with."

"Why don't you leave him with me?" Oh said. "I'm sure I can make a man of him. But I'll only do it on one condition: that when a year passes and you come to get him you will only take him with you if you know him for your son. If you don't you will leave him with me for another year."

"Very well, let it be so," the father said.

They had a drink to seal the bargain, and the father went home, leaving his son with Oh.

Oh led the youth straight to the nether world deep underground and brought him to a green hut with a roof of reeds. Everything in the hut was green: the walls, the benches, and even Oh's wife and children. And as for Oh's maidservants, they were all wood sprites and as green as the greenest of grass.

"Sit down and have something to eat," said Oh to the youth.

The maidservants brought some food, green like everything there, and the youth ate a little.

"And now," said Oh, "go and chop me some firewood and bring it into the house."

The youth went outside, and whether he chopped the wood or not nobody knows, but he lay down on top of the logs and fell asleep. Oh came to see how he was getting on, and, seeing him lying there, had him bound and tied. Then he ordered his servants to bring more logs, and, hauling the youth up on top of them, set fire to them. The youth was burnt to a cinder, and Oh cast his ashes into the wind. A small ember was all that was left of him, but when Oh had sprinkled it with some living water the youth rose up out of it as alive and well as ever but more quick and sharp of wits.

Oh told him to chop some wood again, but the youth fell asleep as he had before, and Oh set fire to the logs for the second time, burnt him to a cinder and strewed the ashes in the wind. He sprinkled the one ember that was left with living water, and the youth came back to life! And no longer was he a good-for-nothing but as nimble and quick a young man as can be found anywhere and more handsome than tongue can say or story tell.

A year passed, and at the end of it the youth's father set out from home to find him and bring him back.

Into the selfsame forest came the father and up to the selfsame tree stump, and, seating himself on it, said with a grunt:

"Oh!"

And lo! there was Oh climbing up out of the stump.

"Good morning, my good man!" said he.

"Good morning to you, Oh!"

"What brings you here?"

"I have come for my son."

"Come along, then. If you know him for your son you will take him with you. But if you don't, he'll have to serve me for another year."

The father followed Oh to his hut, and as soon as they were there Oh brought out a measure of millet. He scattered the millet over the ground just in front of it, and great numbers of roosters came running and began pecking it.

"Come, now, tell me which of these roosters is your son," he said.

The father looked at them, but all the roosters seemed alike to him, and he could not for the life of him have told them apart.

"Off you go home, then!" Oh said. "Your son will stay here and serve me for another year."

The father went home, but as soon as the second year was up back he came again to the selfsame forest and up to the selfsame tree stump.

"Oh!" said he with a grunt.

And lo! there was Oh before him.

"Follow me and see if you can recognize your son this time!" he said.

He led him to a sheepfold, but the sheep all seemed alike to the father, and though he looked and looked again he could not for the life of him have said which was his son.

"Off you go home, then! Your son will stay with me for yet another year," Oh said.

The father went home as sad as sad can be, but when the year had passed he set out for the forest again. He walked and he walked and whom should he see coming toward him but an old man with hair as white as snow and dressed all in white.

"Hello there, my good man!" said he.

"Hello yourself, old one!"

"Where are you going?"

"To see Oh and get my son back."

"How did he manage to get him away from you?"

"It's a long story."

And the father told the old man of the bargain he had made with Oh.

"A bad business!" said the old man. "He'll be leading you a dance for a long time."

"Yes, I know," the father said. "I can't think what I am to do to get my son back. But perhaps you can think of something?"

"I think I can," said the old man.

"Well, then, please, please tell me what I am to do. For whatever my son is like he is my own flesh and blood and I want him back."

"All right, then, listen to me," said the old man. "When you come to Oh's hut he will let out a flock of pigeons and scatter some grain for them to eat. Now, the one pigeon that does not peck the grain and stays by itself under a pear tree cleaning its feathers will be your son."

The father thanked the old man and went on.

He came to the tree stump and said "Oh!", and Oh appeared and led him to his underground house. He scattered some wheat grains over the ground and called the pigeons, and vast numbers of them, each looking like the other, came flying up.

"Now tell me which of these pigeons is your son," said Oh. "If you can pick him out from the rest he is yours; but if you can't, he's mine!"

The father looked at the pigeons and saw that they were all busy pecking the wheat save only one of them, which kept apart from the others and was cleaning its feathers under a pear tree.

"That is my son!" he cried, pointing at it.

"True enough! It is he and you can take him home with you," Oh said.

And he changed the pigeon into a youth so handsome that the like of him could not be found anywhere in the world.

The father was overjoyed and so was the son, and they threw their arms about each other and embraced and kissed.

"Come, let us go home now, son," the father said.

They set out on their way and as they walked along each told the other of all that had happened to him in the three years since they had seen each other last.

The father complained to the son about how poor he was.

"What are we going to do, son?" he asked. "I am poor and so are you, for though you served Oh for three years you earned nothing."

"Do not grieve, Father, we'll make out," the son said. "The young lords will be sure to go fox hunting in the forest, and when we see them I will change myself into a hunting dog and catch a fox. They will want to buy me, and you must let me go for 300 roubles. We'll have money enough and to spare then. Only mind, do not let them have my chain!"

They walked on, and when they came to the edge of the forest saw some dogs chasing a fox. But though the fox was never out of their sight they could not overtake it.

The son at once changed himself into a hunting dog and, going after the fox, soon brought it to bay.

The lords came rushing out of the forest.

"Is that dog yours?" asked they of the father.

"Yes, it is!" the father replied.

"Sell it to us!"

"I don't mind."

"How much do you want for it?"

"300 roubles. But without the chain, mind!"

"What do we want with your old chain! We'll have a gilded one made for the dog. Here, take 100 roubles, and we'll call it a day!"

"No, my price is three hundred and not a kopeck less!"

"Oh, all right, take your money and give us the dog!"

They counted out the money, and taking the dog, put it on another fox's scent. The dog chased the fox straight into the forest, and, getting back its proper shape, came back to the father.

The father and son walked on, and the father said:

"This money we have won't go a long way, son. It will pay for some farm animals and some tools and to fix up the house a bit, that's all."

"Don't grieve, Father," said the son. "There'll be more young lords hunting quail a little farther out. I'll turn myself into a falcon, they'll want to buy me, and you must let me go for 300 roubles. Only mind, don't let them have my hood!"

They started crossing a field and they saw some young lords hunting quail. The lords let loose a falcon, but though it did not let the quail out of its sight it could not overtake them. Then the son changed himself into a falcon and caught one of them, and the lords saw him and ran up to the father.

"Is that falcon yours?" they asked.

"It is," the father replied.

"Sell it to us!"

"I don't mind."

"How much do you want for it?"

"300 roubles, but without the hood, mind!"

"We don't need your old hood, we'll make him a better one!"

They bargained for a while, but finally gave the father the sum he asked. Then they let loose the falcon which flew after the quail. But as soon as it was in the forest it got back its proper shape and rejoined the father.

"Now we have enough to live on!" the father said.

"Wait, Father, we'll get more!" said the son. "We will go to a fair, I will change into a horse, and you will put me up for sale. Let me go for a thousand roubles, but mind, do not sell my bridle!"

They came to a small town where a big fair was being held, and the son changed himself into a horse. And so wild was he that all who saw him feared to come near him. The father led him along by the bridle, but he could not keep the horse from prancing and kicking and pounding the ground with his hooves. The merchants saw him and hurried near, and the bargaining began.

"I want a thousand roubles for him!" the father said. "But without the bridle, mind."

"Cut the price by half, and you can keep your old bridle, we'll make him a silver one!" the merchants returned.

"One thousand is what I ask, and one thousand is what I mean to get!"

Just then the group of people standing around the father and his horse was joined by a Gypsy who, the father saw, was blind in one eye.

"What do you want for the horse?" the Gypsy asked.

"A thousand roubles. And I keep the bridle," the father replied.

"Too steep. How about five hundred with the bridle thrown in?"

"No!"

"Six hundred, then."

"No, I say!"

They went on bargaining, but the father would not take off so much as a kopeck from the sum he had named.

"Oh, all right, you can have your thousand," said the Gypsy at last. "Only I want the bridle too."

"Well, you can't have it!"

"Come, now, who ever heard of a horse being sold without its bridle! How will I lead him away?"

"That's your business."

"Take an extra five roubles and don't haggle!"

"Oh, all right!" the father said, thinking to himself:

"Five roubles is a good deal for the bridle, it's not worth more than thirty kopecks!"

They had a drink to clinch the deal, the father took the money and went home, and the Gypsy, who was not a Gypsy at all but Oh disguised as one, got on the horse and rode away.

The horse flew higher than the trees but lower than the clouds, and he soon brought Oh to his kingdom. They came down by a forest, Oh led the horse into the stable and himself went into the house.

"The. rascal did not escape from me after all!" said he to his wife.

Noon came, and Oh took the horse by the bridle and led him to the river. The horse bent over the water, but instead of drinking it he turned into a perch and swam away. Oh did not think long but took the shape of a pike and swam after him. He was about to seize him, but the perch spread out his spiky fins and turned his tail to him, and he could do nothing. Coming up as near as he dared, he said:

"Please, Perch, turn and face me so we can talk!"

"I can hear you just as well the way I am!" the perch replied, and though the pike swam after him he could not catch him.

The perch swam up to the bank, and, seeing a princess washing clothes, turned into a garnet ring. And the princess saw the ring, took it out of the water and brought it home to show her father.

"Look at the pretty ring I found!" she said.

The father admired the ring, and the princess thought it so beautiful that she did not know which finger to wear it on!

Some time passed, and his servants told the tsar that an old merchant was asking to see him.

The tsar came out of his chamber.

"What is it you want, old man?" asked he of the merchant.

And the merchant, who was none other than Oh himself in a merchant's shape, replied:

"I was crossing the sea in a ship, Your Majesty, and accidentally dropped a garnet ring I was taking to my king into the water. I am only here to ask if anyone of your people found it."

"My daughter did," said the tsar.

He called the princess, and Oh began pleading with her to give him the ring, saying that it was as much as his life was worth not to deliver it to his king.

But the princess would not part with the ring, and nothing could make her change her mind.

The tsar joined his pleas to those of Oh.

"Do give the old man his ring, daughter," he said. "You don't want him to be punished for not delivering it!"

The princess remained unmoved, and Oh said:

"Ask what you will of me, only give me the ring!"

"Neither of us shall have it then!" the princess cried, and she flung the ring on the floor. And lo and behold! it broke into grains of wheat that rolled all over it.

Oh at once changed into a cock and began pecking the grains, and he ate them all save one which he did not see as it had rolled under the princess's shoe. He then flew out the window and away to his own kingdom.

The princess stepped away, and the grain of wheat turned into a youth so handsome that she fell in love with him at sight and began pleading with the tsar and tsarina to let her marry him.

"I will only be happy with him and no other man!" said she.

At first the tsar hesitated to let his daughter marry a common youth, but he talked it over with his wife and gave in. The tsar and tsarina blessed the young couple and held a great wedding feast to which half the world was invited.

I was there too and had my share of the mead and the wine. But it all ran down my beard and not a drop got into my mouth.

And that is why, I'll have you know

My beard is white as the whitest snow!

Ukrainian folk tales

HOME